I am embarrassed by the sacrificial body of Jesus. Don't get me wrong. When I teach undergraduates, I am more than happy to address Jesus's identity as the suffering servant who takes upon himself the sins of the nation. I am pleased to teach how in John's Gospel, Jesus is the light of the world that conquers the darkness of sin and death. I delight in showing how the Lamb once slain in the book of Revelation is a counter-polis to the Roman Empire (and thus every Empire that follows—including our own).

In each case, I seek to lead students beyond a moribund fascination with the death of Christ to its broader location in salvation history, its meaning for humanity hic et nunc. I want students to see Christ's death as a coherent sign, pointing toward a form of life in which self-giving love is the very meaning of existence.

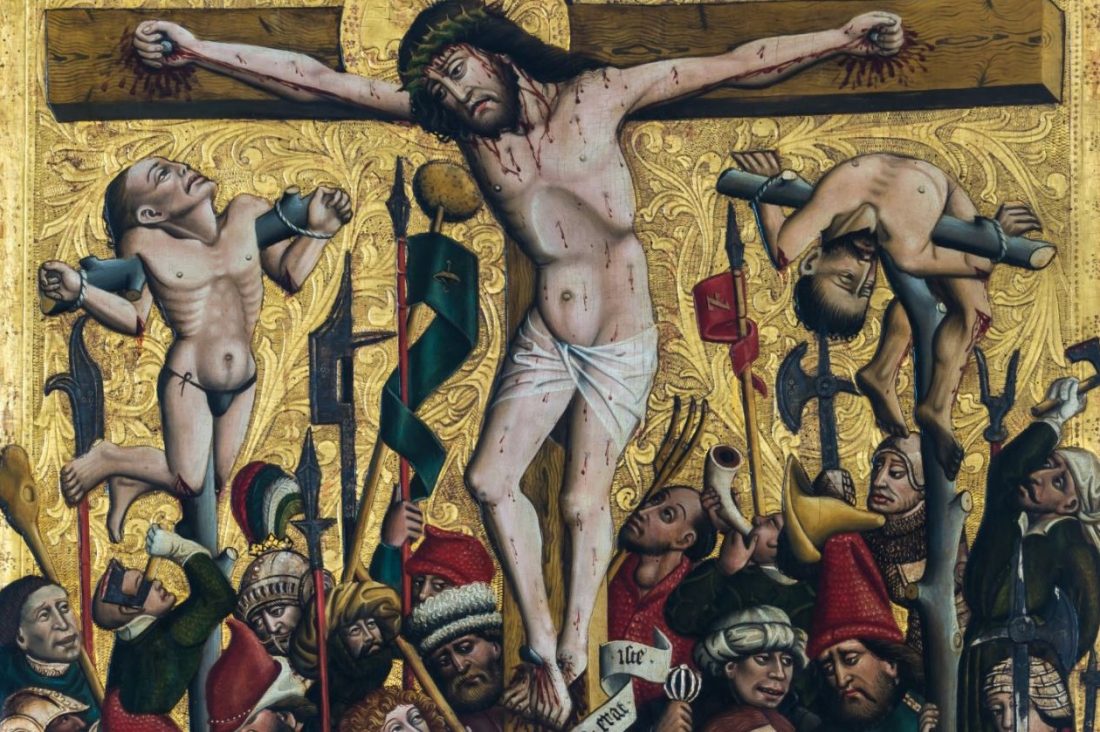

I suspect that I mean well in my approach. But in doing so, I (and thus my students) am too quick to pass over the serious nature of Jesus's death. What it means that the Word made flesh had his flesh ripped to shreds not by a hypothetical darkness but by the shadowy evil of his fellow men. It was his friends who left him alone. It was his co-religionists and the Empire alike who demanded his death.

The prophet Isaiah prophesies:

Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted. But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed (Is. 53:4-5).

Yes, Jesus is the suffering servant who reveals the fullness of what it means to be the beloved son. But he becomes this servant not through an interior act of the will alone but through a bruised, battered, wounded body of love.

Jesus Christ is a sacrifice. A very serious sacrifice.

Why am I embarrassed by this fact? I suppose I might offer an apologia. If we think too much about the embodied nature of Jesus's sacrifice, we might conclude that it is the misery of Jesus's death that redeems the nations. That the Father had to whip up on the Son in order for humanity to be healed. We may grow distracted by the wounds, obsessed with the suffering, and fail to focus on the love that these wounds manifest. A love as strong as death (cf. Song 8:6). And perhaps worst of all, we may conclude that imitating Christ means taking up a form of masochism, one that could lead someone suffering from domestic violence "to just offer it up."

Such a danger, of course, exists. But to pass too quickly over the serious sacrifice of Jesus has another risk—ignoring the flesh of Christ altogether. The great temptation of the heresy of Gnosticism is to turn Jesus into a principle of salvation; oh sure, Jesus has a body, but the real focus needs on Jesus's reign of peace and justice. Jesus comes to abstractly save the world through the principles of justice, mercy, and love. It is our job, as the Church, to apply these principles to the present.

This approach to salvation is problematic for two reasons. First, the Word did in fact become flesh and that is why he saved us. As a recent document from the Vatican, Placuit Deo says:

It is clear that the salvation that Jesus brought in his person does not occur only in an interior manner. In fact, the Son was made flesh, in order to communicate to every person the salvific communion with God (cf. Jn 1:14). By assuming flesh (cf. Rom 8:3; Heb 2:14; 1 Jn 4:2), and being born of a woman (cf. Gal 4:4), “the Son of God was made the son of man” and our brother (cf. Heb 2:14). Thus, inasmuch as He became part of the human family, “he has united himself in some fashion with every man and woman” and has established a new kind of relationship with God, his Father, and with all humanity; we can be incorporated in this new kind of relationship and participate in the Son of God’s own life. As a result, rather than limiting the salvific action, assuming flesh allows Christ to mediate the salvation of God for all of the sons and daughters of Adam (10).

Jesus's death on the cross, his sacrifice, does not just communicate a series of general principles: we must love unto the end, we must stand with those who are oppressed, etc. Rather, through taking on the most horrific of deaths, experiencing radical abandonment, Jesus makes it possible for our very real deaths to become a communion with God. Like Christ, we do not die in an abstract manner. Our bodies ooze and bleed. Our breathing slows as we grasp for breath. Our bodies die. Precisely because Christ took on the two things that all human beings experience in every age—death and life—then every person may be saved.

And that is really what Catholicism is about. It is about salvation. We cannot save ourselves because we cannot rescue ourselves from death. And when we gaze upon the crucified body of our Lord, we are invited to recognize a deep need: to let our deaths enter into the sacrificial logic of the Word made flesh.

In addition, the danger of passing too quickly over the death of Christ means that we refuse to acknowledge how evil we can be as human beings. This propensity for evil is not reserved simply for the bad men and women out there somewhere. It is not like on Twitter where only "those people" are at fault. It was Christ's friends, his fellow members of Israel and the Empire of Rome, that killed him. As we hear on Good Friday in the Reproaches:

I bore you up with manna in the desert,/but you struck me down and scourged me./I gave you saving water from the rock,/but you gave me gall and vinegar to drink./For you I struck down the kings of Canaan/but you struck my head with a reed./ . . . I raised you to the height of majesty,/but you raised me high on a cross.

We too could participate in the violence that ripped apart the body of Christ.

So, I am embarrassed by Christ's sacrifice. Rather than turn from this embarrassment, my healing (and the world's) may require me to adore the cross of Christ. Rather than explain it away.