SPOILER ALERT: This review does indeed contain spoilers.

Some people wanna change, some people want to be stronger... faster... cooler. But don't... please don't lump me in with that. I don't give a shit of what color you are, you know. What I want is... deeper. I want.... your eye, man. I want those things you see through.

—Jim Hudson, blind art dealer in Get Out

1.Get Out has done something that no other film has likely ever even attempted. Writer and first-time director Jordan Peele has crafted a brilliant social commentary using the genre of horror to illuminate the insidious absurdity of racism, drawing uncanny attention to American society’s commodification and consumption of black bodies.

Best known from Key & Peele, his comedic partnership with fellow actor/writer Keegan Michael Key, Peele believes that comedy and horror are connected because, as he says in an interview, “they’re both about the truth . . . If you're not accessing what feels true, you're not doing it right.”

2.Chris Washington, a 26-year-old black photographer living in Brooklyn is dating Rose Armitage, an attractive and affluent white woman and they travel upstate to meet her family for the first time. Chris is nervous in a way that anyone would be officially meeting a lover’s parents, but he directly acknowledges another layer of anxiety since Rose has not told them that he is black. As they cross a threshold, leaving the safety of the city and entering an eerie pastoral setting, the distinctively impressive soundtrack suggests that all is not safe.

Rose’s parents, Missy and Dean, come off as well-meaning wealthy white people whose annoying micro-aggressions serve as a kind of relief. It could be much worse. And yet their two black servants, Georgina and Walter, set off subtle alarms for Chris and for us, the audience; they are creepy. We watch Chris struggle to find a way to relate to them. Rose’s twin brother Jeremy arrives, quickly revealing himself to be the most directly aggressive, but Chris manages to keep his cool, even after Jeremy challenges him physically and implies intellectual superiority.

Rose later acknowledges her family’s weird behavior and is astonished at their social awkwardness; but, overall, Chris is not surprised and is relieved by her support and concern. In many ways, the racially charged scenarios are not that different from the “meet the parents” moments other people experience.

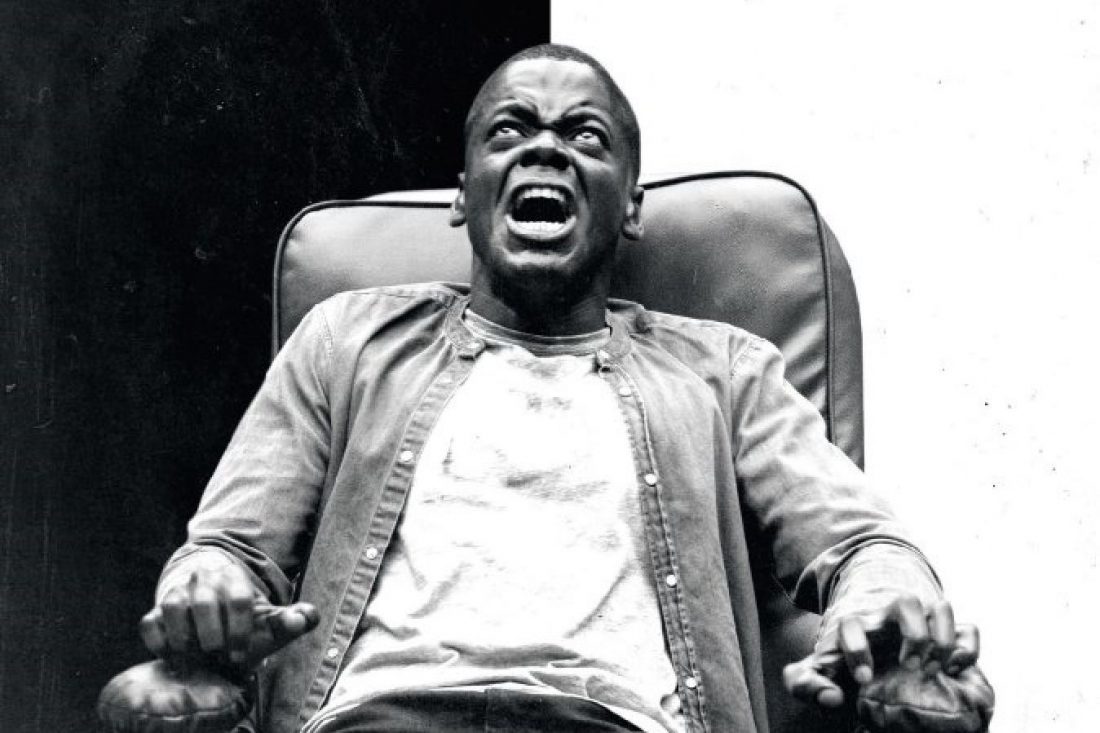

That night everything takes a turn, starting with more creepy interactions with Georgina and Walter. Then Missy, a psychiatrist, slyly hypnotizes Chris to help him stop smoking. She manipulates him into reliving the death of his mother. She uses his childlike, yet, life-defining, guilt to send him into “the sunken place” where he becomes a passenger in his own body, unable to move or speak.

When he awakens the next morning his memory is foggy and guests arrive for an annual soiree that consists of mostly older white couples who are eager to pepper Chris with questions and compliments. Awkward encounter after awkward encounter ensues, leaving both Chris and Rose exhausted from broadly asserted, stereotypically racist assumptions and inquiries into Chris’s supposed racially determined attributes. Allusions to Tiger Woods, and the “coolness” of being black, questions on the sexual prowess of black men, and the relative plight of African-American life wear Chris down.

He attempts to escape the troublesome social situations, only to find himself in another creepy encounter with Georgina, the housekeeper. Chris realizes that he is being tested and it causes tension with Rose; but, like any conscientious partner, he sees it as an opportunity for greater intimacy and reveals his deepest wounds and the shame he feels for not acting when his mother did not arrive home on time.

Chris wants to leave, but he won’t leave without Rose. He won’t abandon her.

They resolve to leave together, but Chris learns that Rose has been lying about her past and when the other family members surround him, she turns. Missy invokes the powers of the already rooted hypnotic suggestions and sends him again to “the sunken place.” Chris collapses, unconscious.

Chris is now certain that he has been the target all along. He comes to in the basement and is told that he is privileged to have been selected. His body will serve as a vessel for a white patron’s consciousness. Chris will remain in a lesser form, stuck in “the sunken place,” watching a better life go on. And yet Chris refuses to give up and fights his way out of this seventh circle of Hell, much to the audiences’ relief. All along, from the beginning of his trek into the country, he is helped by his bumbling and conspiratorially-minded friend, Rod, who has been warning him, in an increasingly alarming argument, by phone, not to trust white people.

3.Peele calls Get Out a “social thriller,” and it is an apt description. It is not until the second or third viewing that one notices how every interaction Rose and her family have with Chris is layered commodification and impending consumption. Chris’s beauty and desirability is made known to the audience from his first appearance. He steps out of the shower and his skin radiates. His life is rich and his photographic eye captures raw and truthful images. Only in hindsight can we see that Rose’s care for him—that he not be racially profiled by, that he stop smoking, that his body not be harmed—is about Chris as a capitalist product to be consumed, not a person to be encountered and loved.

Peele contends that racism in America is horrific. It keeps black Americans and other peoples of color in a constant state of paranoia about the motives of the dominant culture. Do the people around me, who often exercise significant and outsized social power in my life-world, see me as a person to be encountered or as an object, a curiosity in a fantasy, a boogeyman in a nightmare, an ink blot to be analyzed?

4.The many reviews and analyses of Get Out have not said enough about its religious and mythic allusions. It is hard to imagine that in such a film, so painstakingly planned and layered with subtexts, the central character’s name is Chris by accident. He is a lamb brought to the slaughter. The partygoers have come to sacrifice him in order to achieve eternal life for themselves. Peele reveals in a commentary that their backstory is as descendants of the Knights Templar searching for a way to realize the Holy Grail, immortality.

But instead of a lamb, Peele repeatedly uses the less obvious symbol of the stag. In pre-Christian traditions stags have long been signs of purity and connection to the spirit world. Christian folklore has associated the stag directly with the Christ. The first appearance, after being hit by their car, foreshadows the impending danger that Chris will face. He is reminded of the death of his mother and the trauma that undergirds his psyche, which is used by Missy to reduce him to the sunken place.

Dean, Rose’s father, hates the deer species and says the death of the one run over by Chris’s girlfriend was one more “win for humanity.” That deer-encounter comments haunts Chris’s dreams and we see other subtle allusions throughout the film. Once Chris is rendered unconscious and captured, he awakens bound to a chair in the basement. He faces a taximonied stag’s head on the wall. It becomes clear to him and the audience that Chris has been the prey in an elaborate hunt.

5.One of the most important achievements of Jordan Peele’s film is that it uses satire and horror to comment on race while so effectively telling a story about a protagonist with whom it impossible not to empathize. Peele is keenly aware of the power of a story to reorient even racist assumptions. Who could not root for Chris? Who could not see themselves in him and therefore understand his plight and relish in his success? It renders the power of racism mute because Chris is a real person and not just a body.

The film may even ratify traditional Thomistic anthropology: he is body-soul composite. In the end Chris fights for his ontological integrity. American racism attempts to render Chris, and all black people, incomplete: we are either saintly magical negroes (virtually bodiless) lovingly guiding white protagonists (the real human beings) into the fullness of their humanity with our otherworldly wisdom, or, we are beasts who inspire both fear and titillation as we tempt said white folks to satisfy their base desires for danger and sex. Either way, our integrity is sacrificed for the needs of others. We always become instruments in someone else’s narrative; objects, never subjects.

Chris Washington (in a kind of re-Founding) summarily refuses this perverse sacrificial act and we cheer him on. He will not lay down his life. He uses the deer’s sacred antlers to impale Dean. In their physical struggle, when Missy, Rose’s mother, stabs him in the hand with a letter opener, giving him the stigmata, he still refuses to acquiesce. He will not become their willing offering, giving up his body so that others might live eternally.

Perhaps Peele is challenging the undergirding assumptions about the inherent goodness of sacrifice. I do not think so. The Christ willingly laid down his life, demonstrating to his friends what love looks like. There is no love here, only consumption. A Girardian read of “Get Out” would name the violence inflicted upon Chris as the covetous desire to consume the very richness of his distinct and authentically human perspective, necessarily robbing him of the integrity of his embodied-soul. Chris’s survival and flourishing is not in spite of the trauma he has experienced, this is what makes him human. It’s an integration borne of trial and unexpected triumph.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sRfnevzM9kQ