SPOILER ALERT: This review does indeed contain spoilers.

Writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Phantom Thread catalogs what happens when love warps from infatuation and inspiration into competition and resentment. Its enthralling characters, enticing setting, masterful acting, and strenuous plot make for a well-deserved Best Picture nomination, if not a provocative discussion-piece for couples in relationship counseling.

A man of unyielding boundaries living in the ironclad social system of 1950’s London, Reynolds Woodcock (Best Actor nominee Daniel Day-Lewis) personifies luxury.[1] He is a couturier of royal proportions, charming, and desiring companionship. But as a self-described “confirmed bachelor,” Reynolds refuses to be pinned down although he is only ever surrounded by women. His closest confidante and business partner is his sister, the hilarious and somewhat terrifying Cyril (Best Supporting Actress nominee Lesley Manville), who inevitably shoos away every woman futilely waiting for Reynolds to return their affections.

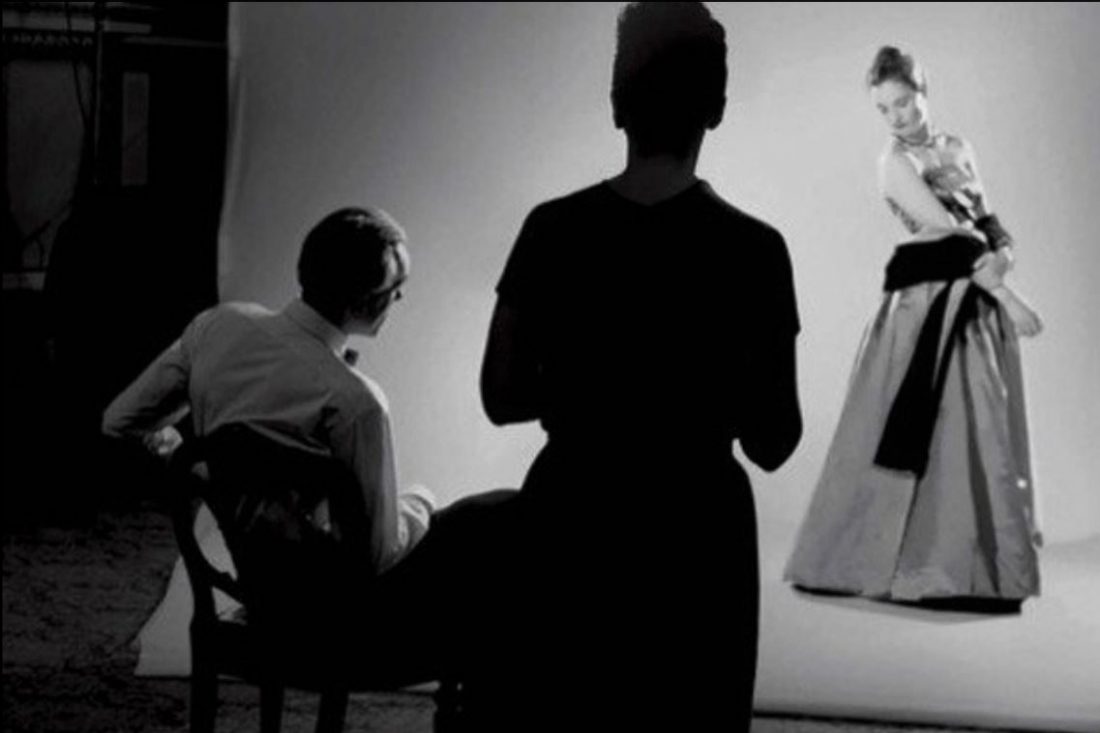

The film’s Gothic set design accentuates the austere tenor at The House of Woodcock and supplements the film’s most sumptuous asset: its costumes. Head designer (and Oscar nominee) Mark Bridges’ vision and craftsmanship provide the film’s aesthetic foundation. This “stuff” and the world of fashion surrounding it make this narrative not merely a warning of the social cost of grandeur and genius, but also a genuine lesson in beauty. We see Reynolds put clothes on women; he believes that dressing women well can help them recognize their dignity.

Complementing the film’s set and costume designs, the soundtrack’s viola-piano arrangements amplify the characters’ fraught relationships and further the film’s eerie, dreamlike quality—a valuable asset in later scenes, keeping viewers off-kilter when one character undergoes a mind-altering experience.

Reynolds’ charm is not entirely pomp. His warmth toward clients appears genuine, if somewhat transactional, and while his eventual lover wonders whether “maybe he is the most demanding man,” Reynolds is not heartless. If nothing else, Reynolds loves the women in his family. His fondness for Cyril—his “old so-and-so”—is fierce and natural. He relies upon her, lets down his guard with her, and defers to her in decisions great and small.

Meanwhile, Lady Woodcock, their phantom mother, so pervades Reynolds’ subconscious that he expresses his devotion to the woman who taught him his craft by sewing locks of her hair into the lining of his coats so he may always “keep her on his heart.” This mother-son relationship offers the film’s most compelling glimpse into Reynolds’ tormented persona; this fealty represents his most human quality, but it is also his source of “sickness unto death.”

When Reynolds visits his country home for some much-needed rest, an unassuming waitress literally stumbles onto the scene and into his life. Enter Alma, played by the commanding and refreshing Vicky Krieps.[2] Reynolds smiles at Alma. She responds likewise.

Her German accent and kind and secure countenance in this post-World War II setting bespeak past struggles: what and who did she leave behind to arrive at this English countryside restaurant? And why does she assent—over and over, we see—to invitations from the clearly-obsessive Reynolds? Anderson’s story provides no ready answers, yet Alma’s repeated “yes” carries with it throughout the film her sense of self—one which is strong-willed and welcoming to possibility. Her name connotes “nurturing” and “soul.” Is she Reynolds’ contrapunto?

Alma plays her part as Reynolds’ muse: she ultimately embraces his etiquette, models his dresses, and learns to play his “behavior games”—all while openly diagnosing his empty show when she must. Early in their relationship, Alma finds herself at the breakfast table with Reynolds and Cyril, as had other women previously (and vainly) seeking Reynolds’ affections. When Alma butters her toast too loudly, Reynolds reacts to this interruption as he always does—peevishly and coldly. Cyril follows suit with iron insouciance. Alma grants their request for quiet, but not without declaring, “I still think he’s too fussy.” Cyril responds with eventual agreement, intimating that the fates may eventually favor Alma’s patient self-possession after all. It is clear that Reynolds, Mr. Immoveable Object himself, is up against an equally capable force in Alma.

Their ensuing romantic due-t may more properly be called a due-l. For some reason, Alma needs to win Reynolds’ love. We are left wondering: when, if ever, is it acceptable to upend the meticulously-curated world of a “genius” if done in the name of love? And at what point can one call a relationship “toxic”?

These questions call upon the viewers to identify the less-than-healthy habits in their own relationships. Choosing sides between Reynolds and Alma would be too easy; we are invited instead to consider, “How am I like Reynolds, and when am I like Alma?” When do I attempt to force my perspective of “what is right” upon another? Do I make love impossible because I am so caught up in my ways? What relationships, or aspects of relationships, or activities, or dreams, are no longer a good fit in my life?

Ultimately, Phantom Thread has the potential to stay with us—like a secret in the lining of a coat—challenging our notions of love and reminding us that love is a force always yearning to build connections and sometimes imposing its will on others in the name of harmony. Whether there is a place for that power struggle in relationships is the phantom thread for each of us to consider.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xNsiQMeSvMk

Featured Image: Detail of Phantom Thread movie poster accessed from IMDB.com, Fair Use.

[1] Resonances between his own personality and Reynolds’ may provide some reason for Day-Lewis’ surprise decision to declare this his final film. The two-time Best Actor winner, who has no plans to see the film, described his decision to walk away from his craft: “Sadness came to stay . . . during the telling of the story, and I don’t really know why.” Day-Lewis is no stranger to playing obsessive, troubled characters, but one cannot help but wonder if this role–the perfectionistic craftsman, born of London–hit Day-Lewis too close to home.

[2] Together with Timothée Chalamet (Call Me By Your Name and Lady Bird), Krieps is perhaps this year’s most pleasant “newcomer” to American film. Her character, Alma, reflects Krieps’ self-awareness, self-confidence, and candid demeanor; just as Krieps has so-far navigated Hollywood’s glamour with sober detachment, so too does Alma fearlessly enter into Reynolds’ world of opulence and pageantry while seeking to remain unaffected by its vices.