I first venerated the cross when I was attending a high-school model UN conference that had been accidentally scheduled during Holy Week. The conference was held in New York City near Times Square, and the neighboring church was the Anglo-Catholic Church of St. Mary the Virgin—colloquially known as “Smoky Mary’s” for the odor of incense that fills your nostrils when you enter the immaculate gothic nave. Its vaults are painted blue with gold stars and lined with red and gold trim. Its interior is perfect. After the passion was sung, we took off our shoes, like Moses before the burning bush, and proceeded through two stations of veneration, each with a server instructing us to bow and proceed, before finally kneeling to kiss the cross itself.

Usually we kiss icons or relics, but why should we kiss an empty cross, and any old cross, at that? In classical literature, metonymy is a figure of speech whereby a part serves to represent the whole. The cross performs a similar function in Christian theology, for it means not only the historical cross of Christ, the two beams on which he was crucified between the thieves on Good Friday, but the event and significance of his crucifixion as a whole. When we say, “the cross,” we mean the fact that Jesus, as God and man, willingly offered himself up to an agonizing and humiliating death for the sake of our salvation. The cross is a metonymy for the theological mystery, this truth of the faith that will always exceed our understanding because it opens to us the heart of God, who will always exceed our understanding.

In this sense, we instinctively think of the cross as beautiful and worthy of veneration. But this is a paradox, for the cross is deeply ugly and must be so in order to be beautiful. On the one hand, something beautiful pleases our senses because of its color, proportion, texture, etc. This is an important part of beauty and cannot be diminished or overlooked. But at a deeper level, the German theologian Romano Guardini argues in his The Spirit of the Liturgy, beauty is the perfect expression of what an object is, of its truth: “Beauty is the full, clear and inevitable expression of the inner truth in the external manifestation. ‘Pulchritudo est splendor veritatis’—'est species boni,’ says ancient philosophy, ‘beauty is the splendid perfection which dwells in the revelation of essential truth and goodness.’”[1]

In this sense, beautiful objects are not only proportionate and unified, but excellent examples of themselves. They express the truth of good things that God has made, both in their parts and in their whole. Moreover, beauty makes the truth perceptible and desirable when it might not otherwise be. Beauty shows us that the truth is good. Take, for example, Canova’s famous sculpture of Cupid awakening Psyche with a kiss, now in the Louvre. We could examine this work in terms of its lines and accuracy, its proportion, the way Canova captures the folds of fabric and the filaments of feathers and the beauty of the human form—all of which are part of why it has become so famous. But what we find so compelling is the way it realizes truths of human love and desire: the tenderness between two lovers, their deep mutual affection, and the way that becomes physically expressed.

Canova’s depiction of Cupid and Psyche speaks these truths in a way that arrests us, which brings us to a second characteristic of beauty: It represents the truth to us in a way that moves us profoundly. Truth primarily impacts our minds, but beauty primarily strikes our hearts and affections. In an address to artists in 2009, Pope Benedict said, “Indeed, an essential function of genuine beauty, as emphasized by Plato, is that it gives man a healthy ‘shock,’ it draws him out of himself, wrenches him away from resignation and from being content with the humdrum—it even makes him suffer, piercing him like a dart, but in so doing it ‘reawakens’ him, opening afresh the eyes of his heart and mind, giving him wings, carrying him aloft.”[2]

In an address to Communion and Liberation when he was still Cardinal Ratzinger, Benedict presses the point even further. He argues that beauty is a greater form of knowledge because it touches us more deeply than rational argument and provides a point of real connection. He writes that “True knowledge is being struck by the arrow of beauty that wounds man . . . Being overcome by the beauty of Christ is a more real, more profound knowledge than mere rational deduction.”[3] In this way, beauty can transform the soul with truth, conforming it to the truth so that it can receive yet more of the truth. Benedict continues: “The encounter with beauty can become the wound of the arrow that strikes the soul and thus makes it see clearly, so that henceforth it has criteria, based on what it has experienced, and can now weigh the arguments correctly.”[4] Beauty provides us with the correct lenses. It gives us the truth in an affective, experiential mode, which can make it easier for us to receive the truth in other modes.

The Holy Father and many use the common metaphor of being wounded by beauty, which reminds us that beauty is painful as well as pleasurable, partly because it reveals to us the beauty of God present in creation and partly because it draws us out of ourselves toward God and the beautiful object. Beauty is thus connected to contemplation and personal encounter. Roger Scruton writes that “Like the pleasure of friendship, the pleasure in beauty is curious: it aims to understand its object, and to value what it finds.”[5] This is why we can stand before a beautiful painting or sculpture slowly soaking in its every detail, or spend hours with a person whose beauty and charm have captured us.

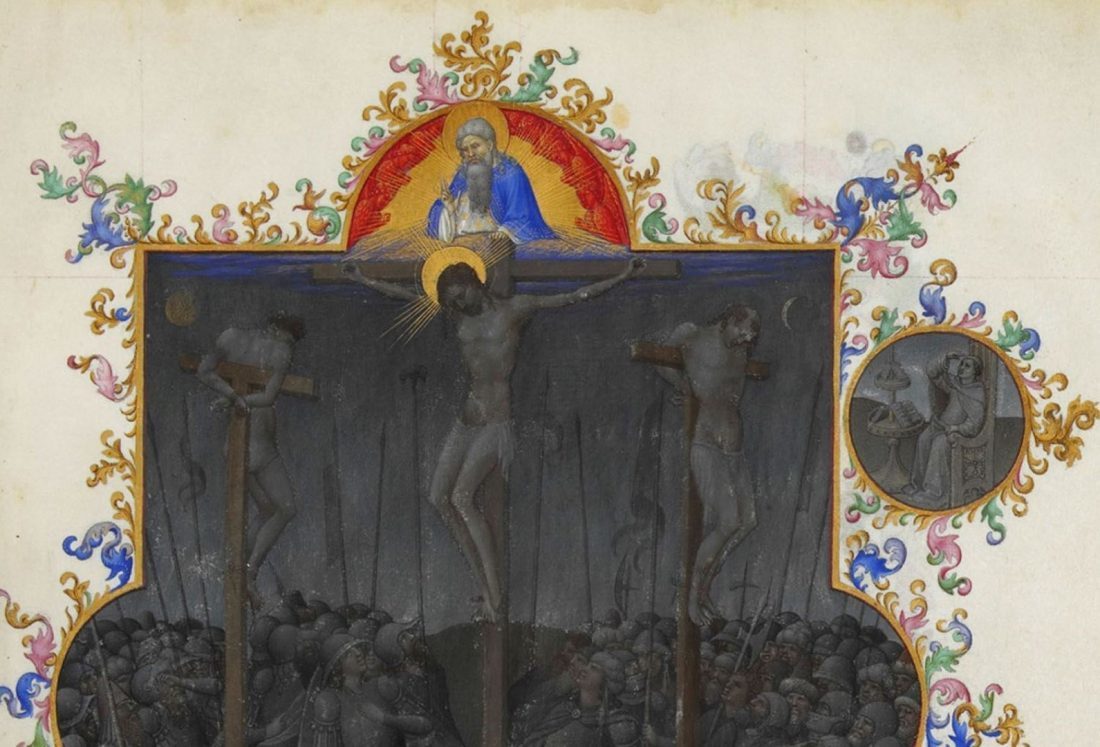

Such a love for Christ—plus a good deal of skepticism about the aesthetic theories he once held—drove the creator of some of the world’s greatest art to reject art for the cross. In his last years, Michelangelo wrote “Neither painting nor sculpture will be able any longer / To calm my soul, now turned toward that divine love / That opened his arms on the cross to take us in.”[6] This leads us to the paradox I posed earlier: Why reject beauty for the cross? The cross is ugly. Crucifixion was so horrifying that the cross is never depicted in early Christian art. Early Christians adopted many common pagan tropes for their own: Orpheus descending to the underworld or the Good Shepherd. Only long after crucifixion had ceased to be a threat would Christians begin to depict Christ crucified in their iconography. Even then, Christ was more often depicted as the Pantocrator, the ruler of the universe, or a teacher. The artistic focus on the cross comes in the high Middle Ages, when devotion to the suffering humanity of Christ as the means of our salvation became important. Still, we tend to diminish the full reality of the cross. Think how many crucifixes we have seen where Christ’s body is unblemished, or with perhaps only a little blood.

Because the cross is horrible, we need to temper its horror in order to receive its truth. We see something similar in the Eucharist. In his treatise on the sacraments, Ambrose writes that we eat a likeness of the dead body of Christ and drink a likeness of the precious blood, “so that there might be no horror at the gore [horror cruoris] and so that the price of redemption might prove efficacious.”[7] He later adds that “We receive the sacraments under a likeness so that the grace of redemption can work.”[8] Later medieval authors quote these sentences repeatedly in Eucharistic treatises when they seek to explain why the Eucharist still looks like bread and wine even after it has changed into the body and blood of Christ. If beauty wounds us and draws us in, ugliness repels us, which means that at some point we will have to temper the ugliness of the cross in order to receive the beauty that might be there.

We can also consider the question of the cross’s beauty through distinctions between different kinds of beauty. Scruton distinguishes between a more modest beauty that we might characterize as ravishing, demanding of wonder and reverence, or filling us with delight and a greater kind of beauty that leaves us speechless.[9] Edmund Burke’s distinction between the beautiful and the sublime captures this difference as well. For Burke, the beautiful is attractive because of its harmony, order, serenity, and proportion. The sublime is beautiful because of its vastness, the threatening power of its majesty, and the fear it inspires in us of our own littleness.[10] In Burke’s terms, the cross has nothing beautiful about it. What we find beautiful, once we can bracket some of its ugliness, is its sublimity.

The cross’s sublimity depends on its ugliness, for the magnitude of Christ’s suffering reveals the magnitude of the sin and evil he took on. The Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar writes:

The Spirit of love cannot teach the Cross to the world in any other way than by disclosing the full depths of the guilt that the world bears, a guilt that comes to light on the Cross and is the only thing that makes the Cross intelligible. Indeed, it is in the God-forsakenness of the Crucified One that we come to see what we have been redeemed and saved from: the definitive loss of God, a loss we could never have spared ourselves through any of our own efforts outside of grace.[11]

The great theologians of the Church, from Athanasius to Anselm, agree that Christ had to take on the full weight of humanity, with all its sin and guilt and wretchedness, in order to vanquish and heal it. And so the cross becomes the place where that sin and guilt and wretchedness are most acutely visible, the ugliness without which the cross could never be beautiful. The Fathers discern the logic that what must be redeemed, must be assumed, and in the process of being assumed it becomes visible to us.

Of course, the cross is not just a display of moral and aesthetic ugliness. It is the moment in which the full beauty of God’s love is most deeply revealed in its victory over that ugliness. Christ not only reveals our sin to us but purifies human nature in offering it back to his Father. In offering himself to the Father and incorporating us into that offering, Christ reveals the form of God in a new way: as self-emptying love. In this sense the cross clarifies the rest of Christ’s life and, indeed, the action of God throughout all of salvation history. And it shows us the love that is the inner life of the Trinity.

John calls Christ the logos, indicating that he is the organizing principle that makes the universe intelligible.[12] The cross shows us that the rational principle of the universe, the ur-form that directs the other forms, is love. Hence von Balthasar writes:

The sign of the God who empties himself into humanity, death, and abandonment by God, shows us why God came forth from himself, indeed descended below himself, as creator of the world: it corresponds to his absolute being and essence to reveal himself in his unfathomable and absolutely uncompelled freedom as inexhaustible love. This love is not the absolute Good beyond being, but is the depth and height, the length and breadth of being itself.[13]

The sublime beauty present in the cross is the sublime beauty of God in the very structure of the Trinity, in the relations between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The human nature of Christ draws its existence from the divine person of Christ the Word. And the Word receives his “form” as a person from his eternal procession from the Father. Von Balthasar concludes, “In the Christian communion of love we share in a personal act of God himself, the tip of which may be seen shining in the person of Christ, but which in its depths contains the interpersonal life of the Blessed Trinity and in its breadth embraces the love of God for the whole world.”[14]

We can now return to our initial theses about beauty and see in what ways the cross is beautiful, and not only sublime. First, beauty expresses truth of something’s form. The cross is beautiful because it reveals the nature of God to us to an unmatched degree. Second, beauty gives rise to contemplation and encounter with the particular beautiful object. Because it brings about our union with God, the cross enables us to encounter God in the person of Christ. Moreover, Christ’s sublime act of sacrifice moves us to wonder and contemplation.

Finally, beauty wounds and moves us profoundly, giving us a knowledge deeper than rational inquiry and calibrates our hearts to receive the truth. The cross moves us because of the sacrificial love we see and its revelation of God’s nature clarifies how we see the rest of the world. If you stand on the steps of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City and turn in one direction, Fr. Richard John Neuhaus notes:

There is the mythical Atlas [in Rockefeller Center] holding up the world; turn in the other, and there [through the doors of the cathedral] is the One broken by the world. Which image speaks the truth? Is the world upheld by our godlike strength or by the crucified love of God? Upon that decision everything, simply everything, turns.[15]

The cross not only helps us understand religion rightly, but all of reality rightly. So often we think of the world of the liturgy, a retreat, or a convent as distinct from the “real world.” Fr. Neuhaus reminds us that the beauty of the cross clarifies that “Here, here at the cross, is the real world, here is the axis mundi . . . It is by this world, this world at the cross, that reality is measured and judged. That other world, the world we call real, is a distant country until we with Christ bring it home to the waiting Father.”[16]

The beauty of the cross wounds our hearts, in the words of de Grandmaison, with a wound that will not heal until heaven. It arrests us because it reveals to us the glory of the Trinity in the glory of the Crucified. It becomes the place wherein Christ incorporates our own self-offering into his, thereby embracing us into the inner life of the Trinity. And it gives us the grace to see the world rightly, so that we might help Christ bring it home into that divine life.

[1] Romano Guardini, The Spirit of the Liturgy, translated by Ada Lane (London: Sheed & Ward, 1937), 114–115.

[2] Benedict XVI, Address to Artists, November 22, 2009, https://zenit.org/2011/07/07/our-world-needs-beauty-pontiff-tells-artists/.

[3] Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, On the Way to Jesus Christ, translated by Michael Miller (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005), 36.

[4] Ibid., 37.

[5] Roger Scruton, Beauty: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 26.

[6] Michelangelo, “Sonnet 285,” in The poetry of Michelangelo: an annotated translation, translated by James M. Saslow (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 285.

[7] Ambrose of Milan, De Sacramentis IV.4.20.

[8] Ibid., VI.1.3.

[9] Scruton, 13.

[10] Ibid., 61.

[11] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Love Alone Is Credible, translated by D.C. Schindler (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2004), 93.

[12] Cf. ibid., 54.

[13] Ibid., 145.

[14] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Engagement with God, translated by R. John Halliburton (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2008), 41.

[15] Richard John Neuhaus, Death on a Friday Afternoon: Meditations on the Last Words of Jesus from the Cross (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 203.

[16] Ibid., 6.