Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD)—the new, sanitized way of describing what we used to call physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia—was listed in 2022 as the cause of 13,241 deaths, up from 1,018 deaths in 2016, the year of its legalization.[1] Certainly, it is not news to find MAiD has become more widely used within a jurisdiction where it is legal, and for proponents of MAiD, this outcome is what they had desired. MAiD is imagined by its proponents to be a good offered by an enlightened and compassionate culture. Yet, we should look more closely at the role played by death in culture generally, and how MAiD has a more pernicious effect on a culture and the individuals who participate in it. While it is true that death is a powerful force in culture, the possibility of choosing death is not just one more option among many others, instead, the possibility of choosing death reframes all options.[2]

Death, Culture, and Meaning

Death and frailty of the body have long been at the forefront of philosophical reflection. In fact, one might argue that culture itself is a response to death in several ways.

Because we are frail beings—prone to disease, disability, and death—we need each other and so we create material cultures to support us in our frailty. We are social and political animals, as Aristotle taught us and Alasdair MacIntyre reminds us, and have need of each other because of our frailties and our dependencies.[3] The institutions of medicine and of law arise in every culture, as do any number of other technologies and institutions, to support the life of our mortal bodies.

Death also forms culture in a different way. Once dead, we are quickly forgotten. Death and its possibility give impetus to our selfish desires to be remembered. We want to leave behind something of ourselves, a way of keeping one’s memory alive. We desire to be remembered as part of the culture’s stories.

These narratives may be captured in stone or in song, in poetic verse, or in architecture. And while these projects can certainly be self-aggrandizing, it is also true that we remember Virgil, Augustine, Dante, or Michelangelo, not because we have become part of their own self-aggrandizing projects, but because what they represented in our cultural artifacts points to something that was true, good, and beautiful about being human.

Put differently, death forces us to contend with what matters most to us as a culture. And material culture—its institutions and technologies—is how we preserve what matters most to the culture. Material culture is our memory of a tradition of what mattered to our predecessors, and what they thought ought to matter to us.

Hans Jonas notes that one could tell what an ancient culture believed about life by examining how they buried their dead.[4] We do indeed find out what ancient cultures believed and valued about the meaning of life by examining their mausoleums from the Pyramids to the Viking ship coffins to the Jewish washing ceremonies of the dead body. The significance of life and the significance of the body as understood by the culture is on display in these burial customs and practices. Thus, the possibility of death is not only the foundation of our material culture, technologies, and institutions, death’s possibility also shapes the meaning of life as understood by the culture.

The possibility of death also prompts one to reflect on what is important for one’s own life. Philosophers throughout history have said that the wise person pays attention to death. From Plato to the Stoics to Martin Heidegger, reflecting upon one’s death is an essential component of the good life or the authentic life. I will not be around to experience what it will be like to be dead, but if I reflect upon my death while living, it can inform how I live and what I live for moving forward.

Death also shapes Christian theology. The Epistle to the Romans notes that, by our baptism “into [Christ’s] death we were buried with him, so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the Father’s glorious power, we too should being living a new life.”[5] Having died to ourselves our lives are transformed such that St. Paul can say, “To live is Christ, to die is gain.”[6] One might even say that liturgy itself is a practice toward death, repeated at least weekly as a kind of repetition of not only Christ’s death but also of our own. Liturgical action is always a retelling of the redemptive act of God in the person of Christ, whose death prompts us to die to ourselves and to rise to new life.

And it is because we have already died and live in the hope of resurrection that we should have no fear to enact justice. We should not fear death at the hands of the powerful; we live in the resurrection already. So, in a way, death is foundational for us, in that it prompts the creation of material culture, as well as the creation of meaning and of value for both a culture and an individual.

Death as Privation

While it may seem perverse to grant such power to create cultures and meaning, I do not think so. After all, it is not really death that sets us off on the journey of cultural creation or personal formation. Rather, death only highlights the goodness, the truth, and the beauty of life, because it deprives us of it. It is life that is good; death only reminds us of that, such that one can now attend to what is truly good and beautiful in life in general and in one’s own life in particular.

Death does not constitute the good, the true, and the beautiful, but because death is the privation of life, it demonstrates—it shows forth—the transcendental nature of life. Life is the condition for the possibility of the good, the true, and the beautiful. Or rather, we should say that life is good, true, and beautiful, even if it is hard to sustain. Living things are mysterious in that they exist in and beyond themselves. Living things—the human animal included—strive to stay alive; they reach beyond the limitations that surround them. Life reaches beyond itself, ever to maintain itself. It has priority over death. Life is; death is not.

Death as privation then merely frames or highlights that life is good and beautiful. It is life that cultures strive to preserve and to perpetuate beyond their own finitude. It is life that gives meaning and purpose. Culture gives witness to what is good and beautiful in life; material culture is a memory-aid passed to us from generations past. That does not mean all material culture is inherently good, for certainly, material culture can propagate evil as well. But in its best forms, it reminds us that beauty and goodness is possible, even as living things die.

The knowledge that I do die—my recognition of the privation that death is—can then creatively inform my living. When we take the privation of death and make it part of our living, our own lives find existence in and beyond themselves. Like God—the source of life—who takes on the privation of death in Christ, and then returns Christ to life in the resurrection, each person participates in her own death and participates in creating her life as a new creation. Thus, even the privation becomes part of the creation.

Culture, Law, and Medicine

MAiD places death into a different frame. It places death, not as the privation that focuses on the goodness of life. Through the lens of MAiD, death appears as a good in itself.

In her essay on the 1997 Supreme Court decision, Vacco v. Quill,[7] Martha Minow insightfully argues that by adding the option of physician-assisted suicide to the doctor’s legendary black bag of therapeutic options, we are not adding one new therapeutic option to the doctor’s list of tricks. Instead, the option for death fundamentally reframes all options.[8] The patient is put into a position to justify why she has not yet chosen death. Minow’s point is that once death becomes a therapeutic option, every other choice appears different.

In fact, there have been concerted efforts to clean up the negative image around death as a therapeutic option. Many bioethicists have argued that we should not use the term “suicide” for those who choose death for medical reasons. Others have noted that we should not say that doctors are “killing” their patients; instead, we should say the doctor is assisting the patient in her death. In fact, MAiD puts the act of “suicide” or “killing” into a respectable context; it is part of all the other legally sanctioned things doctors and nurses do for patients.

Death-causing activity is placed alongside other palliative and therapeutic options deployed by the institution of medicine. Thus, the doctor merely aids one in dying, whether he gives pain medication or symptom-alleviating medication, or gives barbituates or injects the patient with a bolus of Potassium Chloride (which stops the heart from beating), he is simply assisting the patient.

As it is with the individual, so it is for the culture. Once death as therapy is ensconced in law (as it has been in 10 Western countries and 11 states in the US), it takes on a different kind of power. Two of society’s most powerful institutions have enacted what Minow feared back in 1997. Once death is accepted as a good (instead of the privation that it is), it reframes all choices, such that one has to give reasons for not choosing death, and not just for those who have terminal conditions, but for all of us.

We see expansion of MAiD to the disabled like Roger Foley, who having been denied the care he wanted from the NHS of Canada, was offered two options: 1) either pay for the expensive care he needed out of pocket or 2) accept MAiD for no fee.[9] These occurrences are not rare. People living with non-lethal, disabling physical and mental conditions are expensive to support with medical and social services. However, subtly, they are encouraged to avail themselves of MAiD.[10] It is after all a legal option.

Never mind that disability scholars have repeatedly shown us that if social and financial support is given to those who suffer disability, they can flourish and live meaningful lives. If the right services are in place, then patients with disability—physical or cognitive—would not have to choose death; but because death is an option, it fundamentally reframes all options. They will soon be in a position forced to defend why they have not chosen MAiD.

Western cultures are headed down a perverse road where death is not a privation of something good, but is a good in itself, and where terminal patients and disabled persons are placed in situations, however subtle they may be, where they must give justification for why they have refused MAiD.[11]

Medicine, Law, and Power

Medicine and law are products of culture. They are probably the two most powerful institutions in Western cultures.

St. Thomas Aquinas argued that the law—and we might even add, medicine—can be a moral educator by ensconcing precepts in the law that incentivize certain habits of seeing, understanding, and doing the good. Law and medicine can help to promote the virtuous care of vulnerable persons. But law can also educate morally in the other direction.

When the powerful combination of medicine and law reframe death—no longer as a privation of the good, but as a good in itself—it distorts how we understand the truth and goodness of life. It changes how we see and take care of vulnerable persons, for some death is imagined a good. Death as a legal option reframes all other possible choices and educates and habituates the culture into vice.

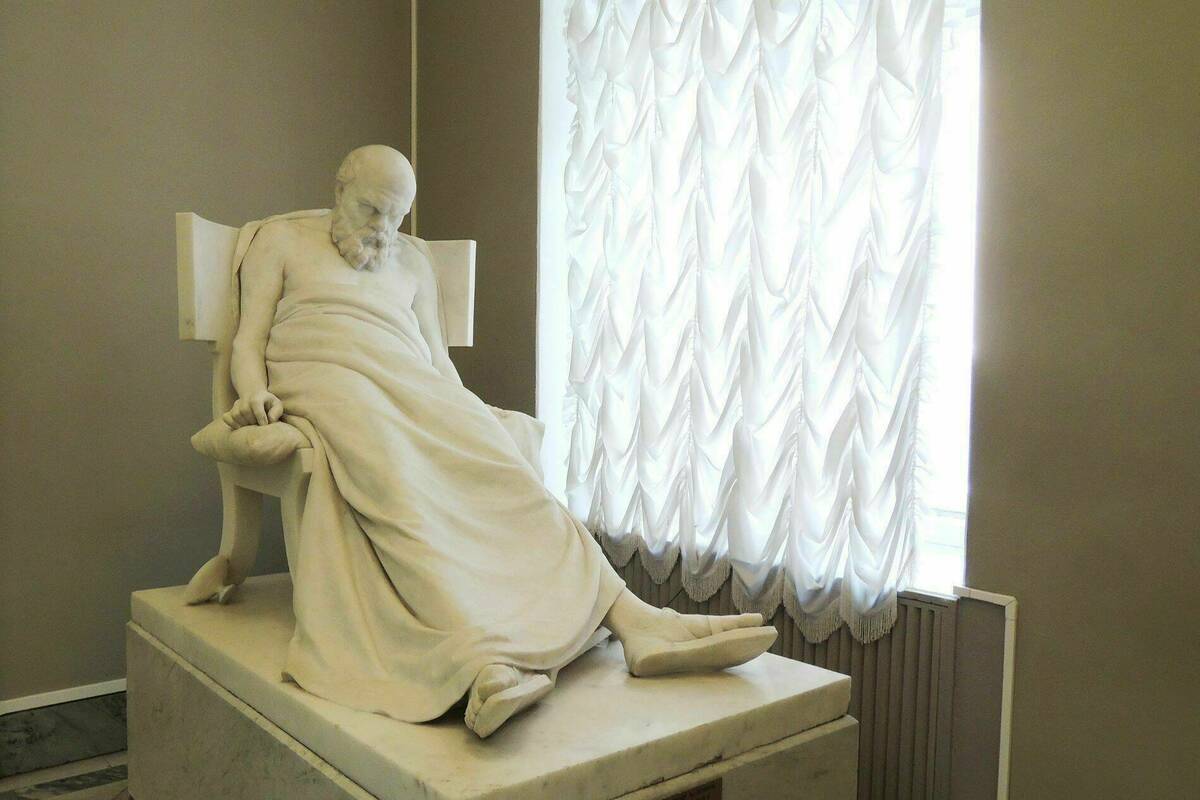

It is shocking to contemplate the possibility that even the great gadfly, Socrates, was seduced by the rationality of choosing one’s own death at the hands of the state. Even he imagined it as a good. Or did he? For even the most casual of readers, the death of Socrates reverberates as a simulacrum of justice. Once death is ensconced as a therapy in medicine, and sanctioned by the state's law, then the culture begins to slip into such macabre and perverse valuations.

[2] Martha Minow, “Which Question? Which Lie? Reflections on the Physician Assisted Suicide Cases,” in Supreme Court Review 1997, edited by Dennis J. Hutchinson, David A. Strauss, and Geoffrey R. Stone. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998, 1–30.

[3] Aristotle, Politics, Book Three, Part IX; Alasdair MacIntyre, Dependent Rational Animals: Why Human Beings Need the Virtues (Open Court: Chicago and La Salle, Illinois, 1999).

[4] Hans Jonas, The Phenomenon of Life.

[5] Romans 6:4

[6] Philippians 1:21.

[7] Vacco v. Quill 521 U.S. 793 (1997).

[8] Minow, “Which Question? Which Lie?” 1998, 1–30.

[9] Harold Braswell, “Canada is Heading Toward a Human Rights Disaster for Disabled People.” See also, Bobby Hristova, “Niagara MPP calls for province to take over ‘disgusting’ Greycliff Manor after 35-year-old dies.”