By the late fourth century, the tomb of Saint Peter was sheltered by an imposing basilica dedicated to his name. In the footsteps of Peter’s early, ignoble devotees came some of the noblest persons of the city. Yet when writing to a friend from Rome in the year 384, Jerome of Stridon was far from celebratory about the increased sophistication of the Roman Church. A prominent priest and theologian, Jerome had come from the eastern shores of the Adriatic. At Saint Peter’s Basilica he paced down the vast, broad nave. There he would meet some of Rome’s highest born ladies. Cloaked in red linen, sat atop litters, encircled by pious eunuchs, these women could hardly be missed. According to Jerome, many of them did not want to be. Unlike the furtive, often fearful Christians of the first centuries of the Church, these noblewomen wished to be known for their faith in Jesus of Nazareth. Like peacocks of piety, they made a stately progress towards their devotions, scanning the streets for onlookers as they passed. Jerome even claimed that they would “disfigure their faces” so that they seemed to have endured grueling penitential fasts. When they encountered an audience, they cast their faces to the ground in a flourish of feigned humility. Yet just as quickly as their gaze had shot down, one eye would stray to discover the identity of their spectator. The Christian churches of Rome, it appeared, had become the places to be seen.

As he wrote his letter, Jerome was vehement, coloring the page with remonstrances for such shows. At Saint Peter’s his horror had sharpened on encountering a lady generally deemed one of “the noblest” in all of Rome. With great ceremony, ringed by a flock of acolytes, this lady had personally distributed a gold coin to each poor soul gathered at the church. This was a great spectacle of Christian charity, but it was a charity with limits that soon became startlingly clear. When a much lowlier woman “full of years and rags” ambled back to the litter to ask for a second coin, the grand lady struck her with such force that blood spilt from her veins. In that moment, Jesus’ calls to humility and charity jarred with the human conceit now present in his Church. The basilica of Saint Peter in Rome was a monument to an apostle glorified for self-sacrifice and humility. Now some of its visitors encountered worldly hubris as they sent their entreaties heavenwards in clouds of heavy, perfumed incense.

By 384, the triumph of Christianity among the noble and ruling classes was becoming a fact. Even in the mid-second century, the philosopher who would come to be known as Justin Martyr claimed—with some credibility—that in his time “more Christians were ex-pagans than ex-Jews.’ But just twenty years earlier the emperor himself had tried to turn the tide against the Church. From the moment he took the throne in 361, Julian I (361–3)—known as Julian the Apostate—worked to cleanse the powerful of Christian influence. If he could only restore the traditional religion of Rome he believed that he could restore the glories of Rome itself. Julian did not have long. Ultimately, he would fail. On the night of 26 June 363, less than two years into his reign, he lay dying from a stab wound that had pierced his rib cage and liver. It is a tradition and somewhat of an irony that Julian dedicated his final labored breath not to pray to his own gods but to that of the Christians. Addressing Jesus directly he is said to have conceded:

You have won, Galilean.

The adoption of Christianity by the richest men and women in the empire took the Church of Rome out of the slums. But it also made the Christian faith a tool of the world. Jerome himself was not alien to this society; he had gone to meet Christian nobles the very day that he witnessed the attack on the poor beggar woman. Jerome often visited the rooms of Rome’s finest palazzi, taking a seat that had likely been occupied before by another great Christian thinker of his age. To Rome came Augustine of Hippo, Ambrose of Milan and those they denounced as errant thinkers or heretics, such as Pelagius and the Spanish bishop Priscillian. Many of these men would ascend to the drawing rooms of Rome’s most salubrious residents, climbing the streets of the Aventine to the Caelian Hills to speak of humility and self-denial in salons of cool, colored marble. There, men such as Jerome sought conversions, personal patrons, as well as supporters for the Church. In counsel and conversations, he and his contemporaries played out the great theological battles of the age. Debating luxury and poverty, free will and divine aid, and the respective values of marriage and virginal chastity, they enlightened and entertained. Such society began to shape the world of the Roman Church, as donations poured in and drawing-room debates spilt out into less salubrious sites. Jerome had merely rebuked the phony philanthropist at Saint Peter’s Basilica. Yet within a year, Priscillian was executed for sorcery after the Bishop of Lusitania and others had condemned him as a pernicious heretic and idolator.

In these years, the wider Christian Church was taking shape, as philosophers and theologians grappled over the true interpretation of Christ’s teachings. Though theological feuds rumbled throughout the empire, Rome became an increasingly crucial node for both discussion and decision-making about the direction and teaching of the Christian Church. As the Bishops of Rome watched their flock expand into all echelons of society, they responded to queries from the lips of the erudite and lowly. In doing so, they defined the beliefs and position of the Church in Rome and beyond. Slowly, the pre-eminence of Peter in Jesus’ eyes was rubbing off on the episcopal see in which he had died: the Church of Rome had begun to emerge as a leading authority in the Christian world.

The growing pre-eminence of Rome as a Christian city was founded on the rock of Peter but accelerated and intensified by powerful new adherents to the faith. It was the emperor himself, Constantine I (306–37), who had raised that mighty basilica to replace the humble markers of the apostle’s tomb. He governed the western half of the Roman Empire from 306, during a period when the Roman Empire was divided in two and ruled by not one but four men. Constantine was the uncle of none other than Julian the Apostate, who would wage bitter war on Christianity during his own rule decades later. Now the story of Constantine as the first Christian emperor is enshrined in history as a moment on which the fate of the entire Church turned. Yet although the consequences were religious and, for many, divine, Constantine’s support for Christianity originated in an unmistakably worldly concern. Like so many turning points in the history of Rome in this transformative period, his decision to patronize the Church was influenced by power, politics, and wealth, as well as religion. The emperor would elevate the worldly presence and status of Christianity. However, his primary object was the lofty office of Caesar Augustus of Rome.

The Bishops of Rome would be elevated on the wings of the emperor’s worldly power. Yet in a startling paradox they would not emphasize imperial glory when shaping the character of their growing Church. For even as the Church of Rome became more eminent in the city and the world, its bishops continued to invoke the blood and bones of martyrs who had been murdered in worldly ignominy. Constantine and the upper classes might have buoyed the rise of Christian Rome with prestige, coin, and opportunity. Nonetheless, it was those Christians who had suffered and died under less favorable rulers who drove the compelling narrative that wrote Christianity into the very stones of Rome.

***

It was not always clear that Constantine was destined to be “the Great.” Since the reign of the Emperor Diocletian (284–305), rule of the vast Roman Empire had been shared out between four leaders—a pair of Caesars in the East and West and, above them, two more senior Caesar Augusti. In one of the first round of appointments, it was expected that Constantine would be made Caesar of the West under his father Constantius (305–6), who was already a Caesar Augustus. The entire assembly was “struck dumb by amazement” when he was totally overlooked. When Constantine heard the news, he sped to his father in York: Constantius would soon breathe his last and his son was taking no chances. Speeding across the continent with such rapidity that his horses died, Constantine arrived in York in the summer of 306. By the end of July the army had acclaimed him Caesar of the West. The four rulers of the empire—or tetrarchy—seemed settled. However, things turned sour when the senior emperors of the West and East proposed to withdraw the praetorian guard from Rome and remove tax exemptions long enjoyed by the Roman people. Enraged at the decision, a trio of officers turned to a man as disgruntled as they were: Maxentius (306–12) who, like Constantine, was the son of a former Roman emperor. Maxentius, too, had been passed over in Diocletian’s imperial appointments. Now, backed by a vengeful army, he saw his opportunity to right the wrong.

It was not difficult to rile a populace facing fresh financial burdens. Rome rose and Maxentius declared himself undefeated prince of central and southern Italy, as well as the African provinces. Incumbent, immovable, Maxentius would materialize his authority in the dense walls of an enormous basilica in the Roman Forum. Flanking the north side of the via Sacra, between the Temple of the Sacra Urbs and the temple dedicated to Venus and Rome, this was not a religious building, like the basilica of Saint Peter, but a basilica in the traditional Roman sense. Maxentius’ building was a place from which to rule and to govern. Underneath its colossal arches he sat, barking out orders. It was later reported that he demanded the felling of all statues of Constantine, whom he had mocked as the son of a whore. Emperors of the tetrarchy, old and new, would bargain with the self-declared prince. They colluded with Maxentius and with one another, but their endeavors to unseat the new ruler of Rome materialized and evaporated without success.

By 311 the government of the Roman Empire was in tatters. Alliances that were once much coveted lay on the scrap heap. Even Maxentius’ father, former Emperor Maximian, had turned against his insubordinate son, teaming up with Constantine to plot his demise. But by the second decade of the fourth century even Maximinus was dead, hanging himself in ritual shame after betraying his latest ally. The alliances got messier still, as Constantine also lost the support of his equivalent Caesar in the East, Maximinus Daza. To make matters worse, the Caesar Augustus of the East, Severus, had turned on him to forge an alliance with Maxentius.

Surveying the city from under a heavy brow, Constantine’s eyes met scenes of treachery, bloodshed, and dysfunction. Yet he also saw a glimmer of opportunity—a chance to overhaul the entire system of government. In an eye-wateringly bold move, Constantine claimed power over the empire not as one of four tetrarchs but as sole emperor, all-powerful and entirely in charge. Constantine made an audacious justification for this volte-face: not only did he claim to be a descendant of Emperor Claudius II, he maintained that he had been chosen to rule by the gods Apollo and Victory themselves. References to their qualities of light, truth and triumph played well in most quarters. Nevertheless, it was not these pagan deities whom Constantine invoked when he finally arrived to take the capital.

There, as he faced down Maxentius on the Milvian Bridge north of the city, he cried to the skies for approval and good fortune, beseeching the one Christian God.

In hoc signo vinces: by this sign you shall conquer. So Jesus himself was said to have told Constantine in a dream. The sign was the name of Christ expressed in two Greek figures: the p-shaped Chi and the diagonal cross of the Rho. Legend tells us that Constantine even saw the figures interlocked in the fiery haze of the sun the day before he arrived in Rome. It was October 312 when Constantine and his 40,000 troops made their slow progress southwards down the via Flaminia to reach the Milvian Bridge, north of Rome. He and his men had only reached the city after weeks of draining travel—barred, battled and, increasingly, welcomed in Italian cities from Susa to Milan. Constantine was not a Christian. Growing up in Nicodemia, he had mixed with followers of Jesus, though there they were an increasingly maligned group. In spite of this, Constantine took the night-time auguries of Jesus to heart. When his soldiers faced those of Maxentius on the 28 October they did so with shields emblazoned with Chi and Rho.

Maxentius too turned his eyes to the heavens for wisdom, but unlike Constantine he did not keep their counsel. For the pagan gods told him to tear down most of the bridges across the Tiber and bed down safely behind the Aurelian Walls. This boundary formed a near impassable barrier of concrete and brick, three metres thick and more than four times as high. Outlandish to the last, Maxentius defied divine wisdom and marched out to meet Constantine in open battle. In haste, his men gathered wood and tools to reconstruct part of the Milvian Bridge, which they had begun to destroy when Maxentius was still heeding the gods. Fate favored Maxentius’ enemy, whether cued by Constantine’s submission to Jesus or Maxentius’ defiance of the pagan gods. Constantine’s cavalry advanced. That of Maxentius was swiftly broken. As his men were driven back across the hastily rebuilt bridge, the wooden parts caved into the water underfoot. Constantine emerged victorious. The following year a writer evoked the dire fate of Maxentius: “the Tiber devoured that man, sucked into a whirlpool, as he was vainly trying to escape with his horse and impressive armor up the far bank.”

***

As another contemporary Christian writer, Lactantius, would declare: “The hand of the Lord prevailed.” Constantine certainly deemed his win a gift from the Christian God. On his triumphant entrance into Rome it is claimed that he did not make the customary sacrifice of thanksgiving to Jupiter—a marked omission and rebuttal of no less than the king of the Roman gods. Instead, Eusebius claims that Constantine honored God, the one Christian deity, erecting a statue of himself wielding the cross in the busiest part of Rome, most likely the Roman Forum. It was a striking decision and, according to some scholars, a colossal statue, as the seated figure measured some twelve meters tall. But even this bold break with convention spoke nothing of the dramatic religious changes that he would soon bring to Rome. Under Constantine, the Christians in the city left the simple obscurity of their house churches to stride through vast, marble-clad buildings raised exclusively for their religion by an emperor who would soon become the greatest ever patron of the Roman Church.

Historians have long labored to temper and nuance accounts of Constantine, Christianity and the rise of the Church of Rome. They have questioned the time, place and sincerity of the emperor’s conversion. They have emphasized his continued patronage and devotion to other cults. They have also underlined the persistence of traditional religions among the Roman people well into the 400s. Evidence suggests that they have been right to do so. Under scrutiny, the heroic story of an emperor and his empire swiftly and utterly Christianized simply does not hold up. And yet Constantine’s triumph on the Milvian Bridge, under the banner of Jesus’ name, did mark a symbolic and physical watershed for the presence of Christianity in Rome. For Constantine dug and filled the foundations of the city’s monumental Christian architecture, making the Roman Church a visible, respectable, state-endorsed institution with a clear physical footprint in Rome. In doing so, he re-shaped the city of his predecessors, with its popular and pagan associations. Incorporating, eliding and suffocating stories of Rome past, Constantine raised new architectural, social and cultural centers in Rome, pregnant with Christian stories and ideas.

This was a pivotal change after years of persecution at the hands of some of the predecessors of Constantine, even if, paradoxically, that persecution was concrete proof of the increasing visibility and presence of the Christian cult in Rome and its empire. The followers of Jesus who lived in the city during Nero’s (54–68) reign were an indistinct group, merging into the Jewish community and the Eastern cults with whom they shared Rome’s lowliest quarters. In the century before the triumph of Constantine, however, the Church was a sizeable and noticeable target. It is likely that the growth of the community was what brought Christians to the attention of men such as Emperor Aurelian (270–75), who ruled a little before Constantine. According to some contemporaries, Aurelian attacked the followers of Jesus, fueled by his piety to pagan gods such as Sol Invictus, the Unconquered Sun. Like his predecessors, Aurelian was unnerved by the burgeoning number of his subjects who flatly refused to engage in traditional Roman rites. Unlike emperors of the past, such as Nero, Aurelian could certainly name the group that perturbed him: Christians. Aurelian, in turn, would be defined by them. Christian texts paint the emperor as a bitter and dangerous enemy of the faith. Constantine himself cultivated his own image in stark contrast to his predecessor. His biographer Eusebius decried Aurelian as a persecutor “slain on the public highway,” filling “the furrows of the road” with his “impious blood.” Drama resonates in these words. Indeed, some have surmised that Aurelian’s role as persecutor was just that: a theatrical invention of Constantine and the historians who wanted to flatter him as a benevolent patron of Christians. In other texts, Eusebius and Lactantius, another scholar who lauded Constantine, claim that Aurelian died (in an act of divine retribution) just before he could enact his anti-Christian laws. Whether Aurelian’s persecution was real, planned or simply invented, these tales make one fact clear. In the minds of Romans, Christians had an inferior, maligned, and potentially perilous status, on the very eve of Constantine’s ascent.

We know for certain that some emperors did attack Rome’s Christian community. They were distressed about the practical effects of impiety to pagan religion. For them, it was crucial that the gods were appeased because religion could unite or rupture their empire. At the turn of the fourth century, Persia, Rome’s most menacing enemy, was united by Zoroastrianism, the Persians’ common faith. Diocletian, the Roman emperor at that time, saw the military strength of his nemesis as one fruit of this religious unity. When he looked upon his own lands, host to the prayers, songs, and ceremonies of a vast array of cults, he could not help but be filled with trepidation. The emperor bristled when he heard stories of oracles made mute and priests unable to read the entrails of sacrificed animals, while Christians, standing by, made the sign of the cross. Harking back to an imagined past of religious homogeneity, Diocletian sought the chimera of a united pagan Rome and, through this, political and military strength for his empire. He would soon engage Galerius (293–311), his colleague in the East, to join him in a dogged and systematic persecution of religious minorities. First, they fixed their attention on the Manicheans, a group who had emerged in the mid-third century and esteemed Zoroaster as a prophet, along with Buddha, Jesus and the Babylonian Mani. On Diocletian’s command in around 302 their leaders were burned alive, their books tossed onto the pyre beneath them. Mere followers could recant. However, if they refused, they too would lose their property, face execution or be marched to a life of hard labor in the mines.

Soon, Diocletian would turn his fiery gaze towards the Christians, enflamed by the fervor of his colleague Galerius. In 303, the emperors seized and destroyed the tools of the Christian religion, lighting fires across the empire to consume books, chalices. and plate. Christians were entirely forbidden to meet for worship. Those who refused to conform lost their status and privileges. Even official employees of the state were enslaved, while imperial edicts dragged others to prison cells. Soon the zeal of the emperors had filled the jails. Clemency was offered to all those who would recant. Still anxious to ensure complete religious conformity, in 304 Diocletian and Galerius demanded that every soul in the empire perform a sacrifice to the pagan gods. The products of a similar edict by Emperor Decius (249–51) in the mid-third century betray the trepidation that these demands stirred up in the hearts of the people. Numerous hastily drafted certificates attest utter devotion to the pagan gods, with men such as Aurelius Sarapammon, a “servant of Appianus,” assuring the authorities that he was “always sacrificing to the gods” and “now too . . . in accordance with the orders . . . sacrificed and poured the libations and tasted the offerings.”

Diocletian’s persecution was vehement and prolonged. Yet his inability to imprison all those who persistently adhered to Christianity illuminates the scale and strength of the Christian cult in his time. By 299, Christians fought in the Roman army. Around the same time, they were working at the imperial court. This presence undoubtedly increased toleration of the cult among some Roman people who lived and worked alongside Christians. While fervent vitriol against the group left a trail of ash and blood in some regions, in others the effects of Diocletian’s orders were surprisingly patchy. By the end of his reign, it is likely that tens of thousands of Christians still walked the streets of Rome, as part of a population of around 800,000. This was largely due to the senior Emperor of the West, Maximian (the father of Maxentius), who was far less zealous in his persecution of Christians than his co-emperors in the East. Despite their ferocity, Maximian was hesitant to enforce the harsher anti-Christian edicts in Italy, and, crucially, in Rome. In that city some books were seized, but many were squirreled away, as Christians handed over just a portion of their scriptures and others gave state authorities books that were not scriptures at all.

It seems that years of marginalization had made the Christians of Rome cunning and tenacious in the face of trial. It is telling that the very first emperor to float the idea of toleration had done so not out of charity but sheer exasperation with the group. Sometime between mid-June and 22 July 260, Emperor Gallienus (253–68), a predecessor of Diocletian, had written a letter addressed to Dionysius, a man who was soon to become Bishop of Rome, as well as “Pinnas, Demetrius and the other bishops.” The letter told the men that they could use the document as proof that “no one may molest” them in their Christian worship. Gallienus claimed that this was something that he had allowed “already for a long time,” in contrast to his father and co-ruler in the East, Emperor Valerian (253–60). This was not filial rebellion. Rather, it was a pragmatic acceptance of the fact that the Christian community in Rome was so resilient that further attacks appeared pointless. When Gallienus relinquished persecution altogether, the Christian group grew even stronger. In 311 in the East, Emperor Galerius was moved to promulgate a similar decree. In his declaration, the Edict of Serdica, he made it clear that persecution had not checked Christian worship. While Galerius conceded that some Christians “were subdued by the fear of danger” and “even suffered death” for their religion, he also conceded that most “persevered in their determination,” met anyway and simply made “laws unto themselves.”

Christians were well aware of the power of persistence. Their heroes were often defined by defiance in the face of threats. Meanwhile, Christians who complied with the demands of their persecutors could be branded with the black mark of treachery. In 303, collaboration with the state’s anti-Christian edicts stained the character of Marcellinus (296-c. 304), the Bishop of Rome himself. He and his priests, Miltiades, Marcellus, and Sylvester, were accused of bending to the emperors’ demands that the Church of Rome hand over its holy books and burn incense for pagan gods. Later Christians and, presumably, Christians of the time, decried the men as turncoats, calling for their immediate expulsion from the Christian community. The sheer force of this disapproval appears to have pushed Marcellinus from Peter’s seat, depriving him of his position and forcing him to his knees at the feet of nearly 200 fellow bishops. This treatment might seem harsh, but the bar was high. Already at this time, less than 300 years since the arrival of Christianity in Rome, there was a tradition of heroic holiness that defied persecution. In the year 250, Fabian (236–50), a Roman noble and the twentieth bishop of the city, offered up his life for his faith. Fabian had rebuffed Emperor Decius’ demand that all sacrifice to the gods and, like the slave Aurelius Sarapammon, produce a certificate to prove it. Just three years after Fabian’s martyrdom, his successor Bishop Cornelius of Rome (251–3) would refuse the same demand and die in exile with his worldly reputation in tatters. Even Emperor Valerian would be defied by a Bishop of Rome. This time it was Sixtus II (257–8) who lost his head. In contrast to these recent brave pastors who had paid the very highest price for defying imperial commands for their faith, the actions of Bishop Marcellinus would have seemed craven.

Under Constantine, such bravery would prove unnecessary. Contrary to some assumptions, Constantine did not leave Rome a Christian city. However, he did legalize and elevate the faith across the empire. Constantine’s resolution to support the Christian Church formally would be made not in Rome but in Mediolanum, modernday Milan. Moreover, it was not a decision that he would make alone. Although Constantine had fought Maxentius on the Milvian Bridge for sole power over the empire, practicalities had forced him into an alliance and, consequently, co-rule with Licinius (308–24), who would become Caesar Augustus in the East of the empire. Just four months after Constantine saw Maxentius drowned in the Tiber, he rallied with his new ally in Milan. There, the two men would discuss a marriage between Licinius and Constantine’s sister, Constantia. Although this coupling and the alliance that it cemented were the focus of the meeting, history remembers it best for an agreement regarding Christianity. The so-called Edict of Milan of 313 assured that the new rulers would “grant both to the Christians and to all men freedom to follow the religion which they choose.” The decision drew together the patchwork of edicts of toleration promulgated intermittently in previous decades. It legalized Christianity across the empire and banned the persecution of Christians outright. Writing in Rome, Lactantius was jubilant about the liberation of Christians from years of persecution, as well as the just recognition of a “Supreme Deity,” by inference the one Christian God. No specific edict has ever been found, despite Eusebius referring to a decree. However, the move to official, permanent toleration of Christians, addressed by both Lactantius and Eusebius, is undoubtedly true.

***

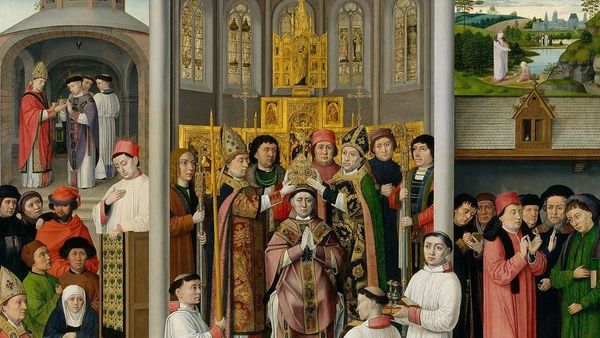

The change brought about by Constantine did not convert the empire or even the city of Rome to the Christian faith. Pagans still dominated the aristocracy in the 380s and it was not until the mid-fifth century that the Roman elite was overwhelmingly Christian. That said, the faith began to seep into the stones of the city almost immediately. Meanwhile, the status and nature of the Church was increasingly colored by the character of empire. Soon, the Church and empire of Rome would be inextricably intertwined in a process of physical and ideological osmosis that raised the architectural cornerstones of Christian Rome that remain to this day. To survive in the city’s shadier corners, the earlier Christian Church had needed simple facilities, basic—even tacit—approval and some sense of unity and direction. As a tolerated, public religion, the demands on the Church swiftly grew. Now, the Church in Rome was called to exhibit its authority and identity, while accommodating an ever-increasing number of faithful. New buildings were essential. Even if Christians could overlook the taint of past pagan worship on existing religious buildings, the structures were simply impractical for Christian ritual. Their center of gravity was outside: a large altar used to sacrifice animals, spilling blood and innards for the gods. Christianity was more like a mystery religion, the rituals of which occurred inside and undercover. The faithful witnessed the ceremony, playing their part in prayer and solemn devotion, whether in a lowly house church or the great Constantinian buildings that would soon be raised in Rome. When Constantine drew Christianity out into the public sphere,

he would give it a home not in the temple but in the basilica, the most grandiose structure of the Roman Empire. Basilicas were where public meetings, ceremonies and even legal procedures took place. When he sponsored these buildings, Constantine took up another imperial tradition: patronizing public architecture. In Rome, his predecessors had commissioned basilicas for the civic good and conveyed their piety by raising temples to the gods of love, war, and commerce. Manifesting his faith in the Christian Church, Constantine repurposed the Romans’ official state architecture for new religious ends. In doing so, he inaugurated the transformation of the term “basilica” into a word that now rings with Christian connotations. Under rectangular roofs, these cavernous spaces had aisles at each side, defined by colonnades and appended with a raised platform at head, foot, or both. Such platforms frequently appeared in the apse, a rounded space usually at the basilica’s furthest extremity, but occasionally along its sides. In some Roman traditional basilicas, a judge would sit atop a formal throne, acting with authority delegated by the emperor himself. In the Christian basilica, it was the bishop who would be enthroned in the seat of oversight and judgement. In Rome, imperial favor had truly elevated the once-derided cult of Christ.

When Constantine built churches, he not only elevated Christianity but also wrote his own chapter in the story of Rome. In 324, the Western world’s first major Christian basilica would appear on the Caelian Hill. The church that would come to be known as the Lateran Basilica, and later San Giovanni in Laterano, was built atop the ruined quarters of the praetorian guard who had sided with Maxentius. Constantine and his mother, Helena, would make this south-eastern area of Rome an important quarter for the religion of the Christians. Ten minutes’ walk westward from that first basilica stood Helena’s Sessorian Palace, where men, women and children would bow down to venerate a piece of wood said to be from the cross on which Jesus himself had hung. In 326, Helena had set out from Rome for the Holy Land, where she used imperial funds to seek out places and objects associated with Jesus and his first followers. Like Constantine she erased recent histories to build Christian monuments for a new age. In Jerusalem, she tore down a temple built by Emperor Hadrian and dedicated to either Venus or Jupiter, plowing foundations for a new Christian building in its place. Wary of angering the Romans, Constantine took a more cautious approach. In Rome, he did not dare construct his Christian basilicas on the sites of pagan temples, or even in the central areas of the city. Yet even if the new buildings of the Roman Church were erected in the outskirts, the effects on the city’s landscape were transformative, permanent, and often dazzling.

Together, mother and son, Augustus and Augusta, built a new Christian cityscape. Gilded with the authority of the state, enriched with the religious treasures of the Holy Land, it grew up in an empire that was changing, gradually but dramatically and forever. On the site of Maxentius’ barracks, the Lateran Basilica stretched to 100 meters in length. The creation of a triumphant ruler and religion, it was dubbed the “Golden Basilica” after the luminous yellow marble with which it was clad. At Helena’s palace, the relics of the True Cross that her builders had unearthed in Jerusalem were dusted off and enshrined in the private chapel in a bejewelled casket of gold. This room was the nucleus of what is now the basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, named for that piece of the cross from Golgotha, now a permanent fixture in Rome.

Snaking across the city towards the north-west, between the Colosseum and the spot where Santa Maria Maggiore would soon stand, Romans could cross the river to reach Constantine’s next major building project: the Basilica of Saint Peter on the Vatican Hill. Just as he had at the Lateran, the emperor erased the past life of the Vatican to construct his city’s future. In building the Basilica of Saint Peter, he would not dismantle the barracks of his enemy, nor stones that had once honored the pagan gods. To level the ground of the muddled, bumpy burial site where Saint Peter lay, Constantine’s builders had to cover the humble monument that Christians had furtively frequented in the first centuries of the Roman Church. The small aedicula, held up by simple marble columns, had marked and protected the site for centuries. Its surroundings were remodeled and hundreds of graves were pushed deeper and deeper into the ground as Constantine built an edifice larger even than the Lateran, stretching to some 122 meters long and sixty-six meters wide. Once the basilica was open, the vast space swelled with the faithful. Casting their glance to the end of the nave, where Mass would be celebrated, they would see Constantine’s name shining out in gold letters atop a triumphal arch.

***

Constantine’s regime had destroyed the buildings of his enemies and erased some pagan places of piety. Now he had swept away the humble roots of the Church of Rome to dig the foundations of what would become a triumphantly Christian city. Principally, however, it was tales of martyrdom that underpinned his basilicas dedicated to Peter, John the Baptist, and Christ himself. Such stories, particularly that of Peter, would remain the surest foundations for this new Christian Rome for many centuries to come.

Christian Rome, later papal Rome, would never be realized in Constantine’s lifetime. Yet its institutional shape and strength were born with his decrees. This included the elevation of the Bishop of Rome, which would facilitate his emergence as pope of the entire Western Church. For Constantine established the hierarchy that still defines the Catholic Church and, at one time, shaped huge swathes of religious, political, and social life across the Western world. At the top of this pyramid, beneath the emperor himself, sat the Bishop of Rome, also known as “God’s consul.” It was he who would take the seat of the judge in the apse of the Lateran Basilica, and it was he who was consecrated to the office in the cavernous nave of Saint Peter’s Basilica. At that time, the Bishop of Rome would be named by a cluster of priests and, acting below them, deacons. The choice could then be ratified by neighboring bishops, such as the bishop of the nearby coastal see of Ostia. The election of a new bishop could also be confirmed or denied formally or informally by the will of the people. This was a process that had begun to emerge before Constantine. With the actions of that emperor, it was cemented, as the significance of the identity and actions of the Bishop of Rome influenced the lives of an ever-growing number of Christians.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted from City of Echoes: A New History of Rome, Its Popes, and Its People with the kind permission of Pegasus Books, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.