In the days leading up to her martyrdom in the Carthage arena in AD 203, Saint Perpetua kept a meticulous written record of her dreams, known to us today as the Passio Perpetuae. The diary describes two visions of her brother Dinocrates, who had died years earlier from a skin cancer at the age of seven. In the first he comes forth from a triste multitude of souls and approaches a basin of water that is too high for him to drink from. Wretched and thirsty, he bears the same wound on his face as when he had died. Distraught by her vision, Perpetua “day and night prayed for Dinocrates, groaning and weeping that my prayer be granted” (Dronke, Women Writers of the Middle Ages, p. 3). A few days later he appears to her again in her dreams, this time healed, radiant, and joyful. The rim of the basin has been lowered to the level of his navel and he drinks from it to his heart’s content, splashing the water the way young boys are wont to do. “I realized then that he’d been freed from pain” (p. 4). Many of her editors take Perpetua’s remark to mean that through the power of her prayer her brother had been “translated” to the realm of the blessed.

These pages from Perpetua’s diary show just how much Christianity did to expand and alter the medium of relation between a living person and a dead soul. Wherever may be the place where the departed live on (and we have seen many such places by now), a Christian believer has intimate access to it, either in spirit, dream, or private petition. Likewise from their side the departed may, when summoned, freely enter the abode of the Christian soul. Through such communion—based on the Christian belief in the afterlife, the efficacy of prayer, and the intercession of saints—the living may influence the fate of the dead, and vice versa. The permeability of that boundary is not specific to Christianity, by any means, yet with respect to the pagan traditions of societies like the one Perpetua was born into at the end of the second century AD, the Christian soul figures as a locus for the afterlife of the dead in a new and distinct sense. Grief, mourning, and remembrance, once the dominant modalities of relating to the dead, now become preludes to hope, expectation, and anticipation. One might say that Christianity rendered the souls of the living and those of the dead continuous in a new way, as if the living soul were in some sense already dead, while the dead soul, in that very same sense, were still alive. Certainly Perpetua’s soul was not of this life, if we understand “life” in strictly secular terms.

When it comes to the nature and the causes of this expansive spiritual transformation that Christianity brought about in the ancient world, there are any number of approaches one could adopt. The ones I will follow here revolve around the meaning of Christ’s tomb in Christian doctrine. If one can come to terms with this article of faith, one goes a long way in understanding the ground of the Christian revolution, for it is from out of Christ’s empty sepulcher that the new religion, as we know it, was born. Whether the historical Jesus was ever laid in a tomb is of little concern here. It is the meaning of the Easter story as it comes to us through the Gospels, and mediated through our own interpretation, that is of primary interest. For life and death, the dead and the living, come together in the Resurrection—whatever that may mean. Let us turn to the Gospel narratives, then, and try to gain some clarity about the events surrounding Easter Sunday.

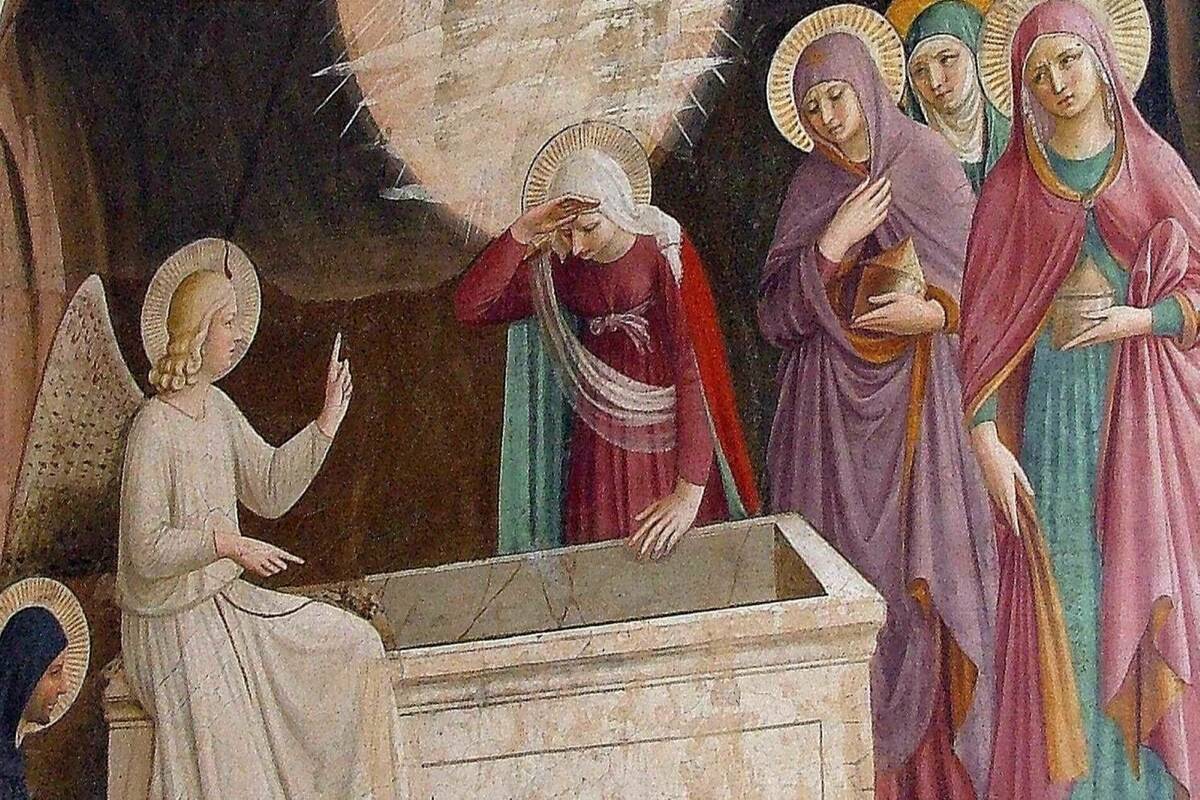

The earliest written account of that first Easter morning comes to us from Mark’s Gospel, composed about AD 70 (almost four full decades after the death of Jesus of Nazareth). Mark relates that when Mary Magdalene, Salome, and Mary the mother of James arrive at Jesus’ tomb on the first day after the Sabbath to anoint his body and complete the rites of burial, they discover that the stone has been rolled away from its entrance. From within the tomb a young man dressed in white tells them: “Do not be alarmed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has been raised: he is not here [hic non est (Vulgate)]. Look, there is the place they laid him” (Mark 16:5–6). The angel alludes to a future appearance of Jesus, although the original Gospel of Mark does not describe any such epiphanies: “But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him just as he told you.” The original Gospel of Mark ends abruptly, with the women running away in fear: “So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid” (vv.7–8). The remaining ten verses, which describe Jesus’ post-Resurrection appearances to the disciples, are later additions to the original text. As for the much more elaborate appearance-narratives in the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John, they were composed anywhere from fifteen to thirty years after Mark’s.

While Mark’s is the oldest written account, biblical scholars, using form and redaction techniques, have been able to isolate the lineaments of an earlier Easter narrative that circulated orally among Christian believers in Jerusalem. This pre-Marcan legend of the Easter event was presumably identical to Mark’s version except for the fact that it contained no mention of Jesus’ future appearance in Galilee. Some scholars have speculated that the story was told as part of a liturgical celebration that took place annually, or perhaps even more frequently, at Jesus’ tomb. Here is how Thomas Sheehan summarizes their theory in The First Coming:

In the first decades after Jesus’ death, the theory claims, believers made pilgrimages to Jesus’ grave “very early in the morning on the first day of the week,” presumably on what we now call Easter, but perhaps even more frequently. At the tomb they would hear a story about women who came there after the crucifixion, found the tomb open, and encountered an apocalyptic messenger, who announced that Jesus had been assumed into God’s eschatological future. The pilgrimage reached its climax when the liturgical storyteller proclaimed, “He has been raised,” and then pointed to the tomb: “He is not here; see the place where they laid him.” The pilgrims’ trip to the tomb to “seek Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified” was meant to end with the insight that the journey had in a sense been fruitless—for why should they seek the living among the dead? (p. 138)

However plausible the theory may be, we will never know for sure whether this is in fact how the Easter story first originated, nor whether the events it describes correspond to real occurrences in Jerusalem in the decades after Jesus’ death. Even if we could, it would not get us much closer to the meaning of Christ’s death for Christians. What historical investigation can establish as matters of fact, and what faith believes about the Resurrection, belong to different, noncoincidental orders of truth. I am interested here in the foundations of the latter, not the empirical grounds of the former. No amount of empirical probing can penetrate the Gospels’ tomb, whose emptiness remains the crux and crucible of Christian faith. It is an emptiness that reveals its contents, or lack thereof, only to those who have already entered the crypt of its sema by way of the sacraments.

Paul never mentions the empty tomb and seems to know nothing about the Easter morning events described decades later in the Gospels, yet one could say that the famous Pauline definition of faith as “the substance of things hoped for and the evidence of things unseen” (Heb. 11:1) has its narrative correlate in the Easter morning story. In all its different versions the emphasis in the Gospels falls on what the women and disciples don’t see when they look inside the tomb, namely Jesus’ dead body. “Look, there is where they laid him.” This there is the site of a disappearance whose void in effect engenders the appearance narratives, all of which are subsequent expansions—some would say misunderstandings—of the story of the empty tomb. If the tomb offers evidence only of what it does not contain, one must look for Jesus elsewhere: in Galilee, in one’s heart, in the community of those who believe in him, in heaven itself. Wherever Christ is, and in whatever mode he exists after the Crucifixion, there is nothing left of him here except the sign of his elsewhereness. “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe.” These words of Jesus from the Gospel of John (20:29), directed against the skepticism of the disciple Thomas, hark back to the scene of the empty tomb and proclaim that Christian faith does not, or should not, rely on empirical evidence of the Resurrection, such as Jesus’ post-mortem appearances to Mary and the disciples. The empty tomb is evidence enough of things unseen.

There is a fundamental analogy, then, between the tomb and the scene of history, both of which Jesus has disappeared from, leaving behind a sepulchral promise that belongs to the futurity of hope rather than to the aftermath of grief. Just as the tomb is full of meaning in its emptiness, so too history is full of that same meaning. While the vocation of faith is to hold fast to the unseen in history, the vocation of the Gospels is to inspire, nourish, and sustain that faith. As Christ passes from the sphere of the seen into that of the unseen, his spirit is consigned primarily to the word and his presence to the sacraments. The Gospels, written both retrospectively and proleptically—looking backward to Jesus’ first coming and forward to his second—speak of this consignment. Indeed, they receive this consignment and, in so doing, point to the evidence of things unseen. One could say that the Christian Scriptures in general—all of which testify to a Christ who has abandoned the scene of history and yet remains operative within it—are written in or under the sign of the empty tomb. On the one hand they are like the angelic messenger who points to Jesus’ disappearance and glosses its meaning (seek not the living among the dead); on the other, given that they were composed anywhere between twenty and seventy years after the death of Christ, the Scriptures are like Mary and the disciples, who arrive at the tomb after the fact. They speak retrospectively of events whose historical traces are found only in their own belated testaments.

The tomb of the Gospels transmutes from within the foundational power of the sepulcher. Hic non est is a deixis that points away from hic jacet; away, that is, from a site marked by its resident dead. If early believers sought out the tomb of Jesus as the site of their commemoration, it was not in order to sacralize the ground of burial but to recall its ultimate vanity. No one underlies this hic. In this sense Christ’s empty tomb distinguishes itself from those “white-washed tombs, which on the outside look beautiful, but inside they are all full of the bones of the dead and of all kinds of filth” (Matt 23:27). Indeed, it distinguishes itself even from “the tombs of the prophets” and “graves of the righteous” which the Pharisees hypocritically “decorate” and make a show of honoring (v. 28). In Luke’s Gospel Jesus compares such Pharisees to “unmarked graves, and people walk over them without realizing” (Luke 11:44). The empty tomb is not such a grave. It is the sign or sema of what escapes its containment.

It is hardly an exaggeration to say that, theologically speaking, the whole earth becomes, for the person of faith, the empty tomb of Easter morning—a place rendered sacred, not because it is swollen with the bones of those who have died, but because its law of death has been overturned by Christ during his residence in the tomb. The three women who arrive at the tomb with spices and oils come to anoint his dead body and fulfill traditional obligations to the corpse of the dead, yet Jesus’ corpse, if ever there was one, has become the new mystical body of Christ. In its resurrected and sacramental plenitude, it does not receive but now dispenses anointment, blessing the earth and giving new life to its otherwise dead matter. In and through that resurrected body, the earth and the cosmos are transfigured. Christ is not here because he is now everywhere—or at least everywhere the church institutes its sacraments. And henceforth there is no place on earth to which those sacraments, and with them Christ’s presence, cannot be brought. Filled with the promise of a new life, the earth as a whole becomes not a conglomerate of places but one new place: the place of Easter morning.

Hence the so-called universalism of the church. The transcultural and transgeographical dissemination of the Christian kerygma, which is potentially at home anywhere, has its theological basis in the utopic transitivity of the hic non est. Instead of being bound to a sacred place, with all the localization and partisan particularity that heroic sepulchers tend to sponsor, the church extends its proclamation to the uttermost ends of the earth. The empty tomb becomes present in its sema wherever the church performs its sacraments. As the institutional correlate of Christ’s triumph over the grave, the church can lay its spiritual foundations anywhere.

Alas, if it were only that simple! On the one hand Christian faith marks a repudiation and transcendence of sepulchral foundationalism; on the other hand, its institutional history shows very clearly that its church retrieved or fell back upon precisely such foundationalism. Rome became its hic. On Peter’s tomb it built its house. While Peter’s bones may in fact be missing from the central crypt, the Basilica of Saint Peter today is nonetheless a veritable “porch at the entrance of a burrow,” to recall Thoreau’s definition of the house. A vast necropolis of tombs—of popes, cardinals, bishops, and dignitaries—underlies its lofty edifice. Not only the Basilica of Saint Peter, but every consecrated Holy Roman church contains the tombs, relics, or bones of dead saints. How is one to account for this apparent contradiction between a theology of resurrection, of which the empty tomb is the sign, and an institutional history that visibly reappropriates the foundational power of the sepulcher? Are we dealing here with a contradiction or instead, a transformation of the meaning of the sepulcher?

Clearly it is the latter thesis that I have been promoting, and I intend to push that thesis further, not by reviewing the foundational history of the Roman church but by bringing to bear on that history certain perspectives that strategically recast and recapitulate some of the basic themes that I have isolated in my work.

To that end I propose to enlist the hermeneutic help of an unlikely book, Marius the Epicurian, written by Walter Pater in 1885. Pater was no theologian or church historian, to be sure; yet in his unusual narrative, which is not so much a novel as a poetic history of the Roman Empire in the third century AD, he offers a singular description of how the early Roman church was in every respect “a porch at the entrance of a burrow.” Painting an unforgettable picture of Cecilia’s house of worship on the outskirts of Rome, Marius the Epicurian probes in impressionistic fashion the deep ritualistic continuities between the Christian Mass and the aboriginal Latin domestic religions. Pater’s fictional representation yields an important insight into the way early Roman Christianity renewed or “sublated” the spirit of those antecedent religions. Thus rather than submit his narrative to a textual analysis I will use its poetic reflections on the founding of the Roman church as another point of entry into the topics that my discussion of the empty tomb has thus far opened up to reconsideration.

But let us start from the beginning. In the first chapter of Marius the Epicurian we are introduced to the book’s protagonist, Marius, who came of age in Latium at the beginning of the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Pater describes how, in his youth, Marius would devoutly observe the pieties of the earliest, autochthonous religion of the Romans, the “Religion of Numa,” which revolved around the worship of ancestral deities in their sepulchral abodes:

The urns of the dead in the family chapel received their due service. They also were now becoming something divine, a goodly company of friendly and protecting spirits, encamped about the place of their former abode—above all others, the father, dead ten years before, of whom, remembering but a tall, grave figure above him in early childhood, Marius habitually thought as a genius a little cold and severe. . . . The dead genii were satisfied with little—a few violets, a cake dipped in wine, or a morsel of honeycomb. Daily from the time when his childish footsteps were still uncertain, had Marius taken them their portion of the family meal, at the second course, amidst the silence of the company. They loved those who brought them their sustenance; but, deprived of these services, would be heard wandering through the house, crying sorrowfully in the stillness of the night (p. 41).

Pater’s reconstruction of the religion of Numa in the first chapter of his fictional biography probably owed more than a little to Fustel de Coulanges’s Ancient City (1860), a book one would expect him to have known well. But against the French scholar, who argued in his conclusion that the rise of Christianity represented a decisive ideological and religious break with the archaic Latin religions, Pater saw in the Christian ritual a profound rescue of what had been most genuinely spiritual and devotional in them. The passage cited above continues as follows:

And those simple gifts, like other objects as trivial—bread, oil, wine, milk—had regained for him, by their use in such religious service, that poetic and as it were moral significance, which surely belongs to all the means of daily life, could we but break through the veil of our familiarity with things by no means vulgar in themselves (ibid.).

Compare this to Marius’s reaction some two hundred pages later when he witnesses for the first time the “divine service” of the Christian Mass, which takes place in Cecilia’s house, or more precisely in “the vast Lararium, or domestic sanctuary of the Cecilian family.” Here a fascinated Marius recognizes an astonishing analogy between the Christian service and the domestic worship that had instilled an indelible piety in him during his childhood:

A sacrifice also,—a sacrifice, it might seem, like the most primitive, the most natural and enduringly significant of old pagan sacrifices, of the simplest fruits of the earth. And in connection with this circumstance again, as in the actual stones of the building so in the rite itself, what Marius observed was not so much new matter as a new spirit, moulding, informing, with a new intention, many observances not witnessed for the first time today. Men and women came to the altar successively, in perfect order, and deposited below the lattice-work on pierced white marble, their baskets of wheat and grapes, incense, oil for the sanctuary lamps, bread and wine especially—pure wheaten bread, the pure white wine of the Tusculan vineyards. There was here a veritable consecration, hopeful and animating, of the earth’s gifts, of old dead and dark matter itself, now in some way redeemed at last, of all that we can touch or see, in the midst of a jaded world that had lost the true sense of such things, and in strong contrast to the wise emperor’s renunciant and impassive attitude towards them (p. 250, my emphasis).

By the time Marius was introduced to the Christian ceremonies he had become an Epicurian devoted to the sanctity of the visible world, though he was still searching (more or less in vain) for the secret of its noumenal origin. He was not yet ready to become a Christian, and even on his deathbed his conversion remains suspended in ambiguity; nevertheless, as a spiritual sensualist he was both captivated and enchanted by Christian sacraments, which seemed to him to respond to, or to arise from, or in any case ceremoniously to acknowledge, the presence of that noumenal mystery that envelops the visible world, lending earthly things their aura of sacrality. Here at last was a religion that reconsecrated the earth and “all we can see or touch,” that blessed the same bread, wine, and oil that the Numa religion, now superannuated, had once blessed within the confines of the family house. Just as the Christian Mass reanimated the “old dead and dark matter” of the earth’s “simple fruits,” so too it seemed to retrieve and expand the sacramental core of a primitive religion that had since died out in the “jaded world” of late paganism:

Such were the commonplaces of this new people [the Christians], among whom so much of what Marius had valued most in the old world seemed to be under renewal and further promotion. Some transforming spirit was at work [in Christianity] to harmonize contrasts, to deepen expression—a spirit which, in its dealing with the elements of ancient life, was guided by a wonderful tact of selection, exclusion, juxtaposition, begetting thereby a unique effect of freshness, a grave yet wholesome beauty, because the world of sense, the whole outward world was understood to set forth the veritable unction and royalty of a certain priesthood and kingship of the soul within, among the prerogatives of which was a delightful sense of freedom (p. 239).

If nothing else this is an excellent example of what Heidegger means by “repetition”—a transfiguration based not on a recycling of the past but on “a wonderful tact of selection, exclusion, juxtaposition” that gives new life to the legacies of a given heritage. Pater’s vision of the “transforming spirit” of early Christianity gives body to Heidegger’s otherwise abstract concept of “liberating one’s inherited possibilities” in repetition. We recall that for Heidegger freedom is the essential element of the anticipatory resolve through which “one first chooses the choice which makes one free” for repetition (Being and Time, p. 437). In a similar vein Pater speaks of the “delightful sense of freedom” with which Christianity “deepened [the] expression” of ancient pieties.

In Pater’s vision the success of the Christian retrieval was due to the fact that the Roman church, like the Roman religion of Numa before it, built its house on and around the tombs of the dead, not only figuratively but literally. He insists on these necrological foundations time and again, but nowhere as compellingly as in the several pages he devotes to describing the vast underworld of catacombs beneath Cecilia’s house, where the early Christian prayer services in Rome took place. This underworld, it turns out, was nothing less than a lararium, or extended family grave, the description of which parallels the earlier description of the lares of the family house at the beginning of the narrative:

A narrow opening cut in [the hill’s] steep side, like a solid blackness there, admitted Marius and his gleaming leader into a hollow cavern or crypt, neither more nor less in fact than the family burial place of the Cecilii, to whom this residence belonged, brought thus, after an arrangement then becoming not unusual, into immediate connection with the abode of the living, in bold assertion of that instinct of family life, which the sanction of the Holy Family was, hereafter, more and more to reinforce. Here, in truth, was the centre of the peculiar religious expressiveness, of the sanctity, of the entire scene. That “any person may, at his own election, constitute the place which belongs to him a religious place, by the carrying of his dead into it”:—had been a maxim of old Roman law, which it was reserved for the early Christian societies, like that established here by the piety of a wealthy Roman matron, to realize in all its consequences. Yet this was unlike any cemetery Marius had ever before seen: most obviously in this, that these people had returned to the older fashion of disposing of their dead by burial instead of burning. Originally a family sepulchre, it was growing to a vast necropolis, a whole township of the deceased, by means of some free expansion of the family interest beyond its amplest natural limits (Marius the Epicurean, p. 229).

Here too we see how third-century Roman Christianity, in Pater’s retelling, had more in common with the older Latin religions than with subsequent, adulterated forms of pagan worship. It even reinstituted the archaic practice of inhumation. As the family lararium became an entire “township of the deceased,” the Christian house (its church) “freely expanded” the concept of family beyond its “natural limits,” in other words beyond the genetic bloodlines that linked the lares to their descendants. It made of all Christians an extended family through their consanguinity with Christ, linked by their shared faith in his redemptive death and Resurrection. This free expansion was the expression of that “spirit of adoption” that Paul speaks about in the Book of Romans. What is expanded here, in Pater’s portrayal, is the core of the earlier domestic religions. In that sense the early Roman church did far more than merely revive certain of its elements. It resurrected their enduring “moral significance” and gave their understanding of the family institution and their veneration of the dead a new expansive spirit.

Pater’s statement that the Christian Mass was “before all else, from first to last, a commemoration of the dead” (p. 249) should be understood in the historical context of the pre-Constantine period, when many of the Christian prayer services in Rome were held in the catacombs. The statement affirms, however, that there was far more to that catacomb scene than clandestinity. In effect, even after the persecutions had ended, the Eucharist continued to be celebrated over the tombs of the martyrs. Later the commemoration took the form of a full-fledged cult of relics. This cult, so maligned by the Protestant Reformers, was certainly no secondary or ancillary phenomenon of church history; it was a crucial element in the foundational history of the church. The martyrs’ deaths were understood as participating in, or repeating, the Savior’s death. Their relics served to ground Christian faith in the putative reason for that death, namely salvation. But how are we to reconcile the cult of saintly bodies and body parts with a faith that believes Christ left no such relics of his own body behind?

The theology on this issue is not entirely satisfying. Preoccupied as they were with securing the institutional foundations of the church, fathers like Jerome and Augustine brought out the heavy artillery against Vigilantius, who in the fifth century opposed the cult of relics on the grounds that it amounted to a form of pagan idolatry. Against the charge of idolatry Jerome argued that by adoring the martyrs’ relics Christians were in fact adoring the Lord on whose behalf they were martyred. Augustine, who saw in the Christ event a radical break with all forms of paganism, went even further and declared the saints’ bodies to be the holy limbs and organs of the Holy Spirit. (It was on the basis of Augustine’s pronouncement that scholastics like Aquinas would later lay the strictly theological arguments for the cult of relics.) In AD 787 the Second Council of Nicea protected and even reinforced the cult by explicitly condemning the contempt of relics and by proclaiming that only churches that possessed them could be consecrated. These relics were and still are often enclosed in the “altar stones” of Roman Catholic churches. When the priest kisses the mensa at the beginning of the Mass he is in effect acknowledging the presence of the dead in the altar stone. Thus does the saint’s body, or part thereof, nourish Christian faith in an afterlife.

The apparent contradiction between a theology of the empty tomb and the Christian cult of relics is resolved only if one conceives of the saints’ bodies as somehow “alive” with expectation and animated by futurity. It was after all in a spirit of affirmation that the prayer services of the early Roman church took place in the catacombs. In this space, which Pater sees as the womb of the Roman church, the living joined destinies with the dead in the promise of the Kingdom of God. Like Christ’s empty tomb, the graves of the martyrs were no more than a sign of what escaped their grasp. The tombs held their relics, to be sure, yet the relics were adored as the evidence of things unseen, namely the promise of resurrection. The saints’ dead bones were the skeletal preludes to a glorified body. This transformation of death into life—this “seek not the living among the dead”—made of the martyr’s tomb a monument of projective hope. One could say that, in some mystical way, the saint’s body or parts thereof brought forth into the church the empty tomb of Jerusalem—or at least its sema.

I have argued elsewhere that repetition can be conceived of as a mode of relating to the dead, of retrieving their legacies from our existential and historical futures. What Pater saw as the essence of the Christian Mass—its commemoration of the dead—was indeed an expansion of life “beyond its amplest natural limits,” that is, beyond the finality of the grave. “But go,” says the messenger at Christ’s tomb, “tell his disciples and Peter that he goes before you to Galilee; there you will see him, as he told you.” Whether this verse in Mark’s Gospel means that Christ was literally raised from the dead and would appear shortly in person to his disciples in Galilee, or whether it alludes to Christ’s universal appearance at the end of time, the crux of Christian faith lies in the notion that Christ “goes before” us—that the meaning of his death, if not the death itself, lies in our future, to be fulfilled either at the end of time or in our own passage beyond the threshold that separates the living from the dead. Likewise the meaning of the martyrs’ deaths lies not with the victimized bodies but with the infinite expectation to which and for which they resolutely gave up their lives.

The Christian commemoration, in sum, was anything but mournful in nature. Grief grieves over separation, whereas Christian repetition (which Kierkegaard defined as a “recollection forward”) saw in death a reaching out into the eschatological future—a future in which and to which the living and the dead remain bound. It is because the logos became flesh in Christ that the living and the dead reestablish their bond in that event, with all its promise. Grief despairs of that promise. In the Old Testament Isaiah prophesizes a time when the Lord will create new skies and a new earth, and when in Jerusalem “the voice of weeping shall no more be heard in her, nor the voice of crying” (Isa 65:17–19). In Revelation we are told that “God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow nor crying” (4:1). These future tenses refer to an eventuality rendered present in the moment of commemoration. For the commemorators the dead already belonged to the ever-present futurity of the Kingdom, and so too did the souls of the believers in the moment of commemoration. Just as the martyrs’ deaths repeated the Crucifixion, so too those who stayed behind repeated, or petitioned again, the Kingdom to come. As they recollected it forward on the tombs of the martyrs they brought the Kingdom forth in the ever-present prospect of their expectation.

It is against this background that we must understand the Christian polemic against immoderate grief and the severity of those legislative proscriptions of excessive public lamentation in the early Christian era. Those proscriptions harked back to Isaiah, Revelation, and the Gospel of Luke, where Jesus denounces the loud ululations that accompanied his climb at Calvary: “And there followed him a great company of people, and of women, which also bewailed and lamented him. But Jesus turning unto them said, Daughters of Jerusalem, weep not for me, but weep for yourselves, and for your children” (Luke 23:27–28). They should weep for themselves because they weep in the first place, hence they despair. With Christ’s coming it is no longer death but sin that calls for grieving. It was certainly in this vein that Paul preached against our natural impulse to grieve for the dead: “But I would not have you be ignorant, brethren, concerning them who are asleep, that you sorrow not, even as others who have no hope. For if we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so them which sleep in Jesus will God bring with him” (1 Thess 4:13–14). Paul goes on to stress that those who will be alive at the second coming “shall not prevent them which are asleep,” in other words they will not “come before” the dead; rather “the dead in Christ shall rise first.” This priority of the dead, stressed time and again by Paul, is what the Christian sacraments commemorate, recalling once again that the dead run ahead of us; hence for the true believer they neither need nor solicit our grief.

Augustine speaks eloquently for this fundamental change in the Christian attitude toward grief in book 9 of The Confessions, which describes the death of his mother, Monica:

I closed her eyes, and a great flood of sorrow swept into my heart and would have overflowed in tears. But my eyes obeyed the forcible dictate of my mind and seemed to drink that fountain dry. Terrible indeed was my state as I struggled so. And then, when she had breathed her last, the boy Adeodatus burst out into loud cries until all the rest of us checked him, and he became silent. In the same way something childish in me which was bringing me to the brink of tears was, when I heard the young man’s voice, the voice of the heart, brought under control and silenced. For we did not think it right that a funeral such as hers should be celebrated with tears and groans and lamentations. These are ways in which people grieve for an utter wretchedness in death or a kind of total extinction. But she did not die in misery, nor was she altogether dead. Of this we had good reason to be certain from the evidence of her character and from a faith that was not feigned (9.12).

As for our Marius the Epicurian, its narrative reinscribes in a powerful way the Christian transmutation of natural sorrow into commemorative celebration. Culling and paraphrasing sentences from the Shepherd of Hermas, Pater records a sermon on the perversity of grief. Here is a sample:

Take from thyself grief, for (as Hamlet will one day discover) ’tis the sister of doubt and ill-temper. Grief is more evil than any other spirit of evil, and is most dreadful to the servants of God, and beyond all spirits destroyeth man. . . . Put on therefore gladness that hath always favour before God and is acceptable unto Him, and delight thyself in it; for every man that is glad doeth the things that are good, and thinketh good thoughts, despising grief” (p. 239).

One must assume that the sermon alludes to Pater’s contemporaries, for whom a certain type of grief had become an endemic, perhaps even interminable cultural condition (hence the anachronistic reference to Hamlet). In the immediate context of the book, however, it is implicitly directed against the emperor Marcus Aurelius, who saw in death the ultimate vanity of all earthly things and adopted a merely stoical resignation to its fatality. Aurelius refused to grieve, to be sure, for he held the dread of death a worse evil than death itself; yet at the core of his imperial melancholy lurked an incurable despair, manifest, among other things, in his “renunciant and impassive attitude” towards those earthly gifts which the Christians meanwhile were reanimating in their liturgies and sacraments. In Marius the Epicurean the emperor embodies the highest wisdom and virtue of which paganism was capable at that point in its long and by now exhausted history. Marcus Aurelius may well have been “one of the best men that ever lived,” as a recent admirer has claimed (Brodsky, On Grief and Reason, p. 291); yet that does not mean that the emperor, at least from Marius’s point of view, was not inwardly wretched and full of dread, or that he did not suffer from a spiritual wound for which neither he nor his physicians nor his philosophers nor the Roman society he presided over in its totality had a cure.

The Meditations were authored by a man who despaired of life, precisely because he despaired of death. For all his attempts to live in accordance with cosmic law Marcus Aurelius had no such “delightful sense of freedom,” which, in Marius’s perception, emanated from the Christian ritual. It was this freedom, or sense of it, that for Marius marked the soul’s true attunement to the order of Creation. Creation is by nature free, yet Marcus Aurelius and his fellow stoics were stoically stifled and shackled. What so many of us in the modern era admire about the emperor is the fortitude with which he suffered his wound, as well as the fact that he was sensitive enough to suffer from it in the first place. He looked through the veil of worldly appearances and saw the underlying absurdity of life. In that respect he remains seductively Hamletian, without ceasing to be Roman. His melancholy, which leaves its subtle imprint on almost every page of the Meditations, not only prefigures Hamlet’s depression but lends it an august authority. That is why we moderns love him so much—he flatters us.

It is astonishing to think that while Pater was writing Marius the Epicurian his fellow (ex-)classicist Nietzsche was on the verge of composing The Antichrist. Nothing could be further removed from Nietzsche’s rant about Christianity’s slave rebellion, with its life-denying, earth-loathing impulses, than Pater’s vision of early Roman Christianity as the spiritual flower of epicureanism. The appeal of Christianity to an Epicurean like Marius lay in the fact that it seemed to reconsecrate the earth, reanimate the senses, and reaffirm the sacrality of life in the face of late paganism’s gloom and desperation. Passages such as the following seem like a direct response, even though they were not intended as such, to Nietzsche’s frontal attack on Christianity as a religion of resentment and denial:

With her full, fresh faith in the Evangele—in a veritable regeneration of the earth and the body, in the dignity of man’s entire personal being—for a season, at least, at that critical period in the development of Christianity, she [the church] was for reason, for common sense, for fairness to human nature, and generally for what may be called the naturalness of Christianity.—As also for its comely order: she would also be “brought to her king in raiment of needlework.” It was by the bishops of Rome, diligently transforming themselves, in the true catholic sense, into universal pastors, that the path of what we must call humanism was thus defined (Marius the Epicurian, p. 242).

The main difference between their understandings of the historical conditions that allowed Christianity to triumph throughout the empire, and above all in Rome itself, is that Nietzsche refuses to address the reality of Roman nihilism, while Pater never loses sight of it. By Roman nihilism I mean Rome’s failure to counter the death drive that had taken hold of the spiritual life of the empire, denigrating the earth and the visible world as a whole. Pater’s central chapters on Roman bloodlust put in sentimental relief the fact that, as death began to lose its sanctity, so too did life, leading gradually but inexorably to a lust for the daily spectacle of murder—of animals, gladiators, criminals, or Christians. Nothing reveals the spiritual exhaustion of the Romans more than their need to incessantly reproduce and inflate the scene of senseless death, a scene which, for those who sponsored or watched it, confirmed that life was as senseless as the immolations in which it found its end.

Where Nietzsche saw the Christian afterlife as a fiction generated by life-denying forces of resentment and vengeance, Pater saw it as the source from which came a new power of blessing, one that possessed the means to resanctify life and bring the dead back into its impoverished sphere. One might say that the afterlife erupted into the midst of the here and now, transfiguring the earth and animating its “old dead and dark matter,” including the bones of saints. Like the old religions whose legacies it retrieved from the futurity of expectation, the church grounded its affirmation of the visible and invisible worlds on its commemoration of the dead, because any consecration of life—be it pagan, Christian, or otherwise—depends first and foremost on regenerating the forces of copenetration, of liberating the past and future reaches of time itself, and of opening the world to what Paul called the evidence of things unseen. Where the dead are simply dead, the living are in some sense already dead as well. Conversely, where the afterlife of the dead receives new life, the earth as a whole receives a new blessing.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted from The Dominion of the Dead (106–123) with the kind permission of The University of Chicago Press, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.