Contagion, suffering, and death are on our minds these days. The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken us from our humdrum, self-assured everydayness and provoked responses anywhere from prudential caution to paranoia. Unsurprisingly, our thirst for curative medical treatment has maybe never been stronger. Ventilators grace news headlines and antibody tests become fodder for dinner conversation amidst this pandemic. Anxiety and paranoia in the face of our finitude, however, at times conceal a more fundamental fear of death.

In some ways, this is reminiscent of the way medicine has been captivated by the novel power of life-sustaining technologies in the ICU since the mid 20th century. The modern hospice movement inspired by Dame Cicely Saunders, though, has sought to correct the one-sided war on death and suffering by calling physicians and nurses back to care for their patients while trying to cure them. Although swamped with COVID patients transferring to comfort care and withdrawing burdensome technologies, Saunders’s hospice and palliative care disciples help patients flourish amidst great suffering in this pandemic. Many have doubled down their efforts to bring spiritual care and personal connection to isolated hospital patients forbidden from receiving visitors.

Their work is made possible by a deeply Christian vision of death. In the best hospice experience, finitude can be experienced as a mysterious remedy to the human condition, offering us hope in this time of affliction.

Death: Curse and Blessing

Anyone who has ever mourned the loss of a family member knows death is a curse. The tragedy of deceased loved ones torn from community, reminds us of a paradise lost, making us feel, at times, as homeless as Adam shut out of Eden. Of course, it was not supposed to be this way from the beginning. Yet, the wages of sin are death (Rom 6:23), and now all humankind lives in slavery to the fear of death (Heb 2:15). Mortality, and especially our fear, usually seems like a punitive sentence for the descendants of Adam.

However, the Church Fathers balance this sense of the privation of paradise with the shadow cast backwards in history from Golgotha to Eden. In an important sense, trumping the first, God mysteriously prescribed death as a remedy for the human condition. The consequences of our sin are to be the means crushing its roots. St. Ambrose says:

What more should we say about [Christ’s] death since we use this divine example to prove that it was death alone that won freedom from death, and death itself was its own redeemer? Death is then no cause for mourning, for it is the cause of mankind’s salvation. Death is not something to be avoided, for the Son of God did not think it beneath his dignity, nor did he seek to escape it. Death was not part of nature; it became part of nature. God did not decree death from the beginning; he prescribed it as a remedy. Human life was condemned because of sin to unremitting labor and unbearable sorrow and so began to experience the burden of wretchedness. There had to be a limit to its evils; death had to restore what life had forfeited. Without the assistance of grace, immortality is more of a burden than a blessing.

Following Christ, Christians are to weaponize their own mortality against sin. The Divine physician’s treatment for the original disease is death, however unpleasant the remedy may seem to our fickle sensibilities. Having trampled down death by death, the cross performs a great reversal of life and death, so that life is Christ and death is gain.

Even logically prior to the cross, the universality of death places a cap on our sin’s destructive power in the world. The lapsarian experience of this vale of tears thankfully comes to an end, just as it did in the days of Noah or the tower of Babel! Otherwise, immortality would approach hell on earth. Mankind is better off with mortal limits to firmly prevent us from escaping our contingent creaturehood.

The blessing of death, if I may speak so boldly, however, is not exhausted by our sacramental initiation to Christ’s Passover via the waters of baptism nor by its ascetical extension in voluntary death to self. Ambrose seems primarily to affirm the blessing of bodily mortality. Our death to sin to live for God is only complete in bodily death as the early martyrs testify. Then, at last, our frivolous pursuits end for good to make us pliable clay in the potter’s hands. He may increase once we decrease.

Modern man has lost touch with the reality of death, however often we speak of it today. We usually enroll professionals to deal with our death and suffering, not realizing how this conceals mortality from us. This means “the idea that life comes through death, and that death therefore has a role to play in life, giving birth to a life beyond the reaches of death, cannot but strike us as bizarre.”[1] I propose the “sanctity of death” in contrast. Hospice patients and those who care for the dying may rejoice together: “O happy death!”[2]

Bodily Death: Birth to Authentically Human Life

St. Ignatius of Antioch speaks of death as a birth. “I am going through the pangs of being born,” he writes to the Romans while approaching the crown of martyrdom. Fr. John Behr keenly points out, taking the lead from Irenaeus, that Ignatius becomes a true human being only in bodily death. Suffering martyrdom in the manner of Christ completes the work of creating human beings, adding Ignatius’s personal fiat where the first man had failed.

At play is a contrast of two modes of coming into being, respectively following Adam and the New Adam. We all necessarily come into existence without our will and will die without our will. Thrown into the world to discover we are beings-toward-death, an existential anxiety often accelerates a myriad of vain pursuits in flight from our human finitude. Plainly, every man dies, but not every man truly lives, as William Wallace says. We must further be clear that the great reversal of the cross obviously does not deliver us from death, but rather from the fear of death.

Apostles, saints, and struggling Christians have all continued to die in the flesh; however, Christ has changed the use of death so that by voluntarily weaponizing it against sin a second birth in the manner of Christ may be enacted. “Rather than being passive and frustrated victims of death and of the givenness of our mortality,” in the words of John Behr, “in Christ we can freely and actively ‘use death,’ in Maximus’ striking phrase, not as an act of desperation, bringing about the end, or as passive submission to victimization, resigning oneself to one’s fate, but rather as the beginning of new life.” In St. Augustine’s words, God creates us without our help, but saves us only with our consent.

This profoundly yokes creation to salvation so that the latter can become the conclusion of the former, revealing the unity in the mind of God.[3] Though Adam preceded Christ historically in the flesh by a great number of years, Christ precedes Adam as the first true human being. He it is that Pilate mysteriously identifies as the paradigmatic man: “Ecce homo” (John 19:5). In other words, we become a new creation not apart from nature or against it, but by completing it with our human freedom as the basis for existence in Christ. We transition from Adam to Christ by our use of death.

Jesus of Nazareth’s death was not simply because he was human (What sin could be found in him?), nor was his resurrection simply because he was God. The full grandeur of the Paschal mystery was an innocent victim’s submission to death though it had no hold on him. The way in which he died as a human being, lifting up agape for all to see, shows us what it is to be God. Love so great to voluntarily assume the cross is shocking and utterly foreign to the sons of Adam. Nevertheless, picking up where the first man failed in the proper use of freedom the God-man sets things straight, and shows us the path to truly human life that should have been Adam’s as well. God and man are brought together “without confusion, change, division, or separation” in the spirit of Chalcedon so that the divine person of Christ assumes the human property of mortality while the human assumes the divine property of life.

Thus the martyr is the ideal Christian, which is to say the martyr is a true human being, their flesh vivified by the Spirit of Christ rather than Adam’s breath. This constitutes the difference between the pre- and post-resurrected body that is “sown physical” and “raised spiritual,” in the language of 1 Cor 15:42-45. The “spiritual body” that has been raised remains ever the body that was “sown physical,” yet it can, at last, truly live by voluntarily using death to be born to life in Christ.

Mortality: A Needed Education

The great reversal where death becomes a birth to human life by voluntarily using it like Christ, however, requires an education in creaturehood. The human freedom incorporated into the cross was a mature willfulness only potentially present in us infants in Christ. Would Adam and Eve have been ready to receive such a splendid gift as divine life straightaway? We need exercise in virtue, righteousness, and self-mastery to discipline our wills, and be capacitated to receive divinity. We are still gestating in the Church’s womb of new life, hoping to be born fully developed, neither premature nor stillborn.

Thankfully, mortality reminds us of our weakness, our creaturehood contrasted with the Creator. Experiencing finitude firsthand reveals the greatness of God’s strength, instructing us to respond freely to God in love, again picking up where our first parents failed in Eden. Death firmly educates us in contingency. Any other approach undermines the freedom of love, and, “rather shockingly,” Behr says, “if we ignore all this, and especially the need for experiential knowledge of our own weakness: we kill the human being in us.”[4] Only by embracing our finitude contrasted with the strength and immortality of God can we begin to appreciate the gift of God in Christ. We need maturity to freely use our death as St. Ignatius and all the martyrs to become, at last, true human beings bringing our own creation to completion. We need first to understand that Christ’s death shows us what it is to be God, and second to be habituated to it.

After all, we cannot ultimately evade death. We can deny it by extending bare biological life or anxiously re-creating our own body to conceal its finitude and creaturehood. Exhausting ourselves as experience machines, calibrating the proper dials to perpetuate artificial bodily perfection, pleasure, and aesthetics only reveals the nihilist despair in the face of death it seeks to hide: it kills the human being in us. Death can either magnify existential anguish by imprisoning us within our “thrownness” into time or it can therapeutically educate us. In both responses, death reveals we are not God, opposing drives of the last 100 years de-naturing our bodies, so to speak, in creation of a new, artificial body deeply alienated from the mind, not to mention traditional Christian anthropology. As Hervé Juvin says, “Alone the body remembers that it is finite; alone, it roots us in its limits, our last frontier (for how long?); and even if—especially if—it forgets, the body alone still prevents us from being God to ourselves and others.”[5]

The cultural and institutional denial of death—i.e., the fear of death—continues uneasily to guide healthcare today. On the one hand, the optimism of curative medicine takes “all illness and human suffering,” including aging and death, as essentially “products of disease whose mechanisms can eventually be understood” and therefore mastered in a Baconian tone.[6] Hospice and palliative care, accepting the limits of medicine, accordingly remain generally a secondary concern to the aggressive extension of life. On the other hand, strong bipartisan support behind recent legislation suggests a shift in cultural priority toward care for the dying. This is good news. Countless patients and families have benefitted from the advent of modern hospice in the last century, and many healthcare workers provide compassionate care for the terminally ill.

Yet, we must not be seduced by the simplistic logic that more hospice equals better deaths. Hospice may be necessary today as a medical and social route away from the technological imperatives energizing the contemporary ICU, but it is not sufficient for two important reasons. First, hospice can be tempted to conflate the painless, palliated death it can secure for a good death.[7] The basic assumption of mastery over death, in this vein, often prevails via overly-aggressive pain and symptom management that too-easily sacrifices consciousness or intentionally hastens death. Nutrition and hydration, too, may be withheld inappropriately, especially from unconscious patients. This contrasts with traditional valuations of awareness and allowing death to take its course.

Second, the many professionals involved are tempted by their expertise to replace the primacy of spouses, children, and priests from the deathbed under an assumption of discursively mastering death. Confessing one’s sins, for example, can become a secondary concern to bio-psycho-social assessment and intervention, enclosing death and dying within scientific and secular boundaries. Generic spiritual assessments and interventions driven by professional protocols, in particular, can subtly coerce patients into a certain kind of death fashioned in the image and likeness of the social sciences, as Jeff Bishop has deconstructed. Where death cannot be defeated, its authority can be subdued by professional discourse and once more recapitulate medicine’s drive to master death. Taken together, our novel surrogates for traditional ways of caring for the dying unite to deny and evade death, despite the irony of admitting the technological limits of medicine. In death, though, the body remembers its creaturehood as corruptibility takes a definite grip.

Good hospice and palliative care sub specia aeternitatis, that is, from a God’s eye view, confronts and sets aside the war on death so prevalent in medicine. It challenges physicians, nurses, and all who care for the suffering to an appreciation of their activities broader than the narrow, calculative medical optimism aiming to overcome death and suffering. Christian hospice care embraces finitude in the “foolish logic of the cross” (1 Cor 1:18-25).

Hospice: Kenosis to Theosis

Christ’s cruciform inversion of death fashioning it as a remedy for sin speaks good news to the dying and those who care for them. The end of life can be a beautiful period acknowledging the dignity of dependence. Better yet, the immanence of death sharply refocuses what matters, even for friends and family dropping their commitments to spend time with them and remember their own death. Aging and dying initiate our kenosis, our self-emptying, involuntarily, as Daniel Hinshaw suggests. Across biological levels, we see the shortening of genetic telomeres, organ dysfunction, wrinkles, and wasting of body mass in cachexia progressing without our will to humble us. The universal features of aging and dying invite the whole person to a voluntary kenosis.

The dying person and those who care for them—especially the many friends and family gathered around the deathbed—find themselves on the threshold of eternity. Not only does the departing soul embark on its final, cosmic journey; it has the amplified opportunity to weaponize death as a remedy for sin. Christian hospice, inasmuch as it encourages the dying to embrace their mortality in the manner of Christ, thus performs a great work of mercy. It makes the deathbed holy, even a heavenly experience, as kenosis can hardly be separated from theosis. God “highly exalted him” who “humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death” (Phil 2:8-9).

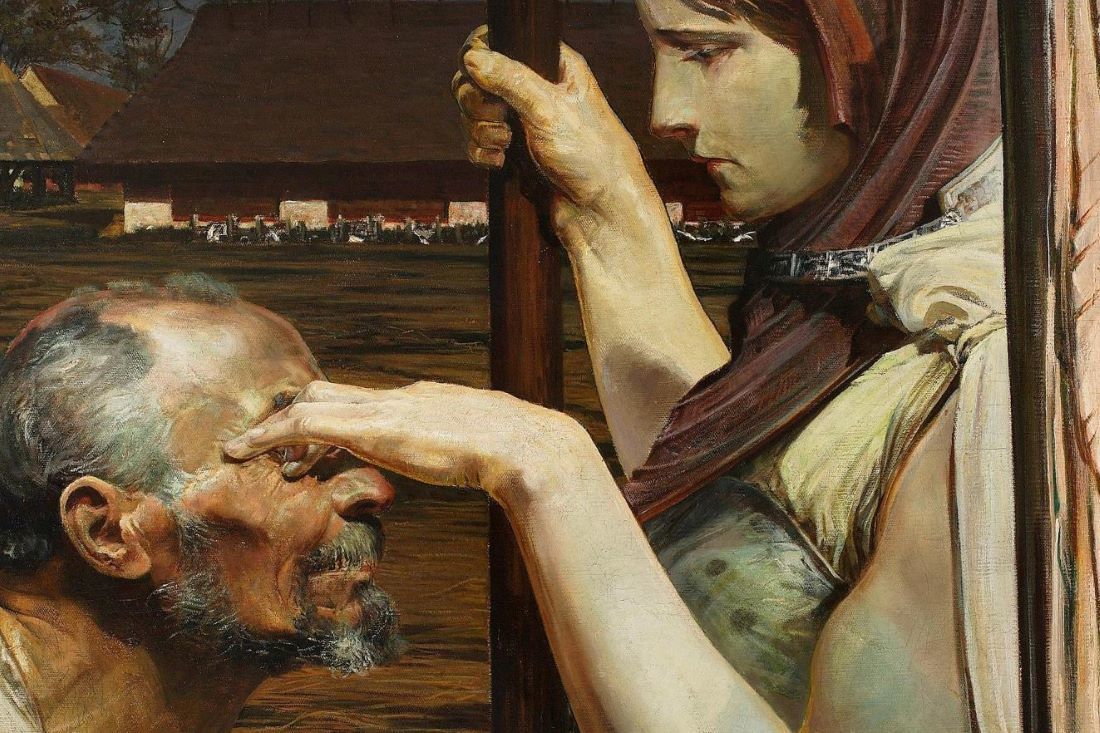

Henry Novello argues that “our death as a dying into Christ . . . should be treated as a “privileged” moment for the beholding of God and the transformation of our being.”[8] A holy death reveals a cruciform love in the dying person. It births the Christian into authentically human life akin to St. Ignatius while manifesting a ray of heavenly light for the community gathered around. In the Son of God’s voluntary assumption of our humanity, what could be a more human experience to undergo than death? For Novello in fact, the incarnation is completed progressively as God takes on man’s properties, concluding in death as the humblest moment of humanity. Such a lens throws fresh understanding on man’s theosis, then, as reciprocally transacting at the point of death, the lowest occasion of kenosis.[9]

The theological richness bathing the deathbed in heavenly light strikingly recasts hospice, and by extension all of medicine, as a religious activity. The physician’s opioids, for example, are drawn up into the mystery of Christ by relieving suffering as the Good Samaritan, enabling the patient to prepare for death with an attentive mind. Christians have always known caring for the sick and dying to be a practice of mercy.

The sanctity of death subverts assumptions trapping medicine in an immanent language of treatment algorithms, burdens, benefits, rights, and efficiency that struggles to see itself as more than a social-scientific or technological enterprise. It similarly challenges mainstream bioethics to see death as more than something to be mastered by advocating for more aggressive palliation or the autonomous patient-subject’s demonstration of freedom in assisted suicide. The mere universality of death seems to suggest a kind of transcendence irreducible to questions of biology or autonomy.

Beholding the blessing of death, of course, is not to deny its sting (for now) nor our own fear. Who could ignore the forsakenness of the cross? Christ himself prayed, “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (Ps 22). Kenosis is hard work. However, the psalmist continues, “He has not spurned or disdained the misery of this poor wretch.” Rather, “I will live for the LORD.” We can learn to pray with St. Francis, confessing the sanctity of death: “Praised be You, my Lord, through our Sister Bodily Death, from whom no living man can escape.”

[1] John Behr, “Life and Death in the Age of Martyrdom,” In The Role of Death in Life: A Multidisciplinary Examination of the Relationship between Life and Death, eds. John Behr and Conor Cunningham (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2015), 95.

[2] The Easter Exsultet, singing the perfect praises of the light of Christ, sings: “O truly necessary sin of Adam, destroyed completely by the Death of Christ! O happy fault that earned for us so great, so glorious a Redeemer!”

[3] Behr, “Life and Death in the Age of Martyrdom,” 85-92.

[4] Ibid., 90, referencing St. Irenaeus, Haer. 4.39.1

[5] Hervé Juvin, The Coming of the Body (London: Verso, 2010), 177.

[6] Daniel B. Hinshaw, “The Kenosis of the Dying,” In The Role of Death in Life, Eds. John Behr and Conor Cunningham.

[7] Farr Curlin, “Hospice and Palliative Medicine’s Attempt at an Art of Dying,” in Dying in the Twenty-First Century: Toward a New Ethical Framework for the Art of Dying Well, ed. Lydia Dugdale, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015).

[8] Henry Novello, “New Life as Life Out of Death,” In The Role of Death in Life, eds. John Behr and Conor Cunningham, 99.

[9] Ibid., 107-119.