The shutdown of American schools due to the pandemic involuntarily thrust millions of parents into the role of teachers or co-teachers—a task which they had hitherto entrusted to public and private schools. Some parents, though still receiving assistance from their schools, are struggling, and are reaching out to experienced homeschooling parents for advice. On another front, homeschooling has emerged as a controversial legal topic with the publication of the essay, “Homeschooling: Parent Rights Absolutism vs. Child Rights to Education & Protection,” by Harvard Law’s Elizabeth Bartholet. Her position is summarized in Harvard Magazine by Erin O'Donnell in the article, “The Risks of Homeschooling,” which is generating intense debate.

Bartholet’s 80-page essay bases its argument upon these stereotypes:

- homeschooling is a nearly unmitigated harm to children and society

- it allows parents to abuse their children, free from the risk that teachers will report them to child protection services

- it causes children to be underdeveloped intellectually and socially

- it shelters children from exposure to views that might enable autonomous choice about their future lives

- children miss out on exposure to others with different experiences and values

- and, children are indoctrinated into closed-minded fundamentalist Christian beliefs at odds with the mores of the zeitgeist.

Most of us, whether we educate our own children or not, are familiar with these charges. Nonetheless, we can acknowledge that these stereotypes are based on the behavior of some people. This small set of examples is then generalized to the entire population of homeschoolers, as if there were no diversity within their community. In other words, Bartholet’s charges are valid in some cases but not in most.

Nonetheless, she urges government intervention to free homeschooled children from their parents and force them to be educated in public schools, where they will learn “correct values,” democracy, tolerance, open-mindedness, etc. She even advocates a presumptive ban on all homeschooling, with very few exceptions, mostly for extraordinarily talented kids like musicians and athletes whose dedication to their craft justifies modified learning schedules.

Bartholet’s argument is not new. It largely echoes James Dwyer’s Religious Schools vs. Children’s Rights, except the former focuses on homeschooling primarily, while the latter focuses on private religious schools. In fact, the argument over private vs. public education is ancient. It reappears regularly in the history of educational and political philosophy—a history seemingly unfamiliar to Bartholet. Therefore, let us pause a moment, step back, and get some perspective from that broader educational history, then examine some Catholic Social Teachings to see if we can come up with a more balanced perspective. As we proceed it will become apparent that the modern homeschooling phenomenon serves as a window into larger philosophical, historical, religious, and legal debates.

The Enduring Issues and the Statistics

The homeschooling movement began in the late 1960’s. By 1978 there were around 12,500 children educated at home. By 2010, estimates ranged from 1.5 million to 2.04 million, and today, 2.5 million. Nowadays, homeschooled students equal the number of public school students in the state of New York, and exceed the number of public school students in the states of Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Montana, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming combined. During recent decades legislatures in most states have passed laws permitting home education, and all 50 states allow it in one form or another.

Parents educate their children at home for a variety of reasons: educational, social, political, and religious. While the majority of homeschoolers are conservative Christians, a broad cross-section of Americans from diverse economic, social, and religious backgrounds undertake it. There are homeschoolers who are secular, Catholic, Evangelical, Jewish, Muslim, Mormon, Native American, and New Age. There are “unschoolers” who allow the child’s natural interests and innate abilities to determine the direction of the educational program. What unites these diverse people is the belief that parents themselves can provide a better education at home than can state-approved schools, and that they have a fundamental legal right to do so.

Homeschooling has many fierce critics and we already went through some of their objections above. Tara Westover’s best-selling memoir, Educated, depicts a survivalist homeschooled family in Idaho that fails miserably to educate its children. Her story reinforces the most negative stereotypes about fundamentalist homeschoolers, though the book is not an attack on homeschooling itself. Yet, Westover wrote with sympathy and love for her family, even while criticizing their abuse. Bartholet rightly points to Westover’s story, and a few others like it, but then attempts to claim such cases are the norm among homeschoolers. Surely, a Harvard law professor is aware of the legal maxim that hard cases make for bad law: it is never good to use extreme cases as a basis for general laws.

Home educators attempt to counter the objections with a host of studies showing that home-educated students consistently outperform their public school counterparts on standardized achievement tests; that they participate in community and civic activities at a rate equal or higher than their public school counterparts; and they do well academically regardless of the educational level of their parents.

Divergent educational philosophies underlie both the acceptance and the rejection of home education. A central political and philosophical issue surrounding the phenomenon is the proper relationship between individuals, families, and the state. Some political theorists assert that parents have an absolute right to control the education of their children. Others assert the absolute right of the state to control the education of the young, even against the wishes of the parents—so as to form citizens loyal to the state or to protect the rights of the children vis-à-vis their parents. Let us briefly examine this centuries-long debate from historical, philosophical, theological, and legal perspectives.

A History of Education and the State

Conflicts over education have a long history, going back at least to ancient Greece. In Sparta education was designed for the benefit of the city-state rather than the individual. The body politic controlled family life and essentially “owned” the child from the time of its birth. At age seven, boys were taken from the home and placed in a state institution for training. There they became children of the state. They lived together and had all things in common. The goal was to train these boys as warriors who would defend the city.

In the Republic, Plato advocated taking children from the home at birth and raising them in common. Children were to be held in common by the city-state, raised and educated by “Guardians” who would engender powerful bonds of loyalty between individuals and the state. No child would know who his or her natural parents were. In Plato’s scheme, the family must be eliminated if the ideal city was to be free of the discord caused by private or kinship loyalties. Aristotle’s Politics presents a similar ideal, but maintains that intermediate associations, between the individual and state, were acceptable as long as the goal of the broader city-state was served.

Variants of these Greek themes on the relation between family and state roles in education echo throughout Western political thought. Jean Bethke Elshtain noted how “all twentieth-century totalitarian orders labored to destroy the family as a locus of identity and meaning apart from the state.” Totalitarianism seeks to “govern all of life; to allow for only one public identity; to destroy private life; and most of all; to require that individuals never allow their commitments to specific others—family, friends, comrades—to weaken their commitment to the state.”

In Some Thoughts Concerning Education, English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) encouraged an educational ideal based on close observation of the child’s innate abilities, use of tutors of high moral character, and avoidance of the negative peer influence and socialization common in the schools of his time. Educational techniques must be fitted to the talents and capacities of each individual, and this cannot be done in schools were one teacher has many pupils. Only the parent or tutor is capable of this. Locke’s educational thought as based on the same philosophy as his Two Treatises on Government, i.e., the dignity, freedom, and independence of the individual who has natural rights which those in power must not violate. The aim of education is to instill in children the virtue and wisdom necessary for living in the world and becoming free and responsible citizens.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) is an inspiration for many progressive home-educators, especially “unschoolers.” In Emíle, Rosseau said a child should be brought up in the country, away from the nefarious influence of contemporary social life. Education is more a matter of removing obstacles that hinder natural development than an imposition of “bookish learning,” he says. The child must therefore develop according to his or her nature, in direct contact with the natural world. The only book Rousseau allows Émile to have is Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, because its theme deals with an individual’s resourcefulness when thrown into a natural state.

Ironically, unschoolers tend to ignore the broader social and political thought of Rousseau’s The Social Contract, where he totally subordinates the individual to society. The larger society has a “general will” that absorbs the individual and may compel absolute obedience. Individual loyalties to any social group less than the state should not be tolerated. The child, wrote Rousseau, “must see the fatherland when he first opens his eyes, and must see nothing else until he closes them in death.” Disobedience could even lead to death.

In America, Thomas Jefferson believed that politics and education are inseparable. He knew that the new American nation could not survive if its citizens were not educated. “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free,” he wrote, “it expects what never was and never will be.” He advocated a system of education “at the common expense of all,” yet wavered when it came to making education compulsory because doing so might violate the parents’ natural right in relationship to their children. He championed locally-run schools and opposed state government control of education. In an 1816 letter to Joseph C. Cabell he wrote, “If it is believed that . . . elementary schools will be better managed by the governor and council . . . or any other general authority of the government, than by the parents within each ward, it is a belief against all experience.” Jefferson wanted the state to fund education, but he wanted control to remain at the local level. Yet he recognized that consensus about education had not yet been reached.

Jefferson’s ideals were also motivated by concern over how America could “absorb a massive influx of immigrants with different traditions and beliefs.” Such influxes could undermine national unity, he believed. This anxiety and xenophobia over foreign immigration increased during the 19th century following the large wave of immigration beginning in the 1840’s, many of them Catholic.

No one advocated for common schools and compulsory education more energetically and articulately than Horace Mann, Superintendent of Education in Massachusetts from 1837 to 1849. Mann championed public schools as the sole means of stamping out ignorance, crime, vice, and aristocratic privilege. They would foster democratic patriotism against old-world tyrannies and would assimilate immigrants by transforming them into “virtuous, productive American citizens.”

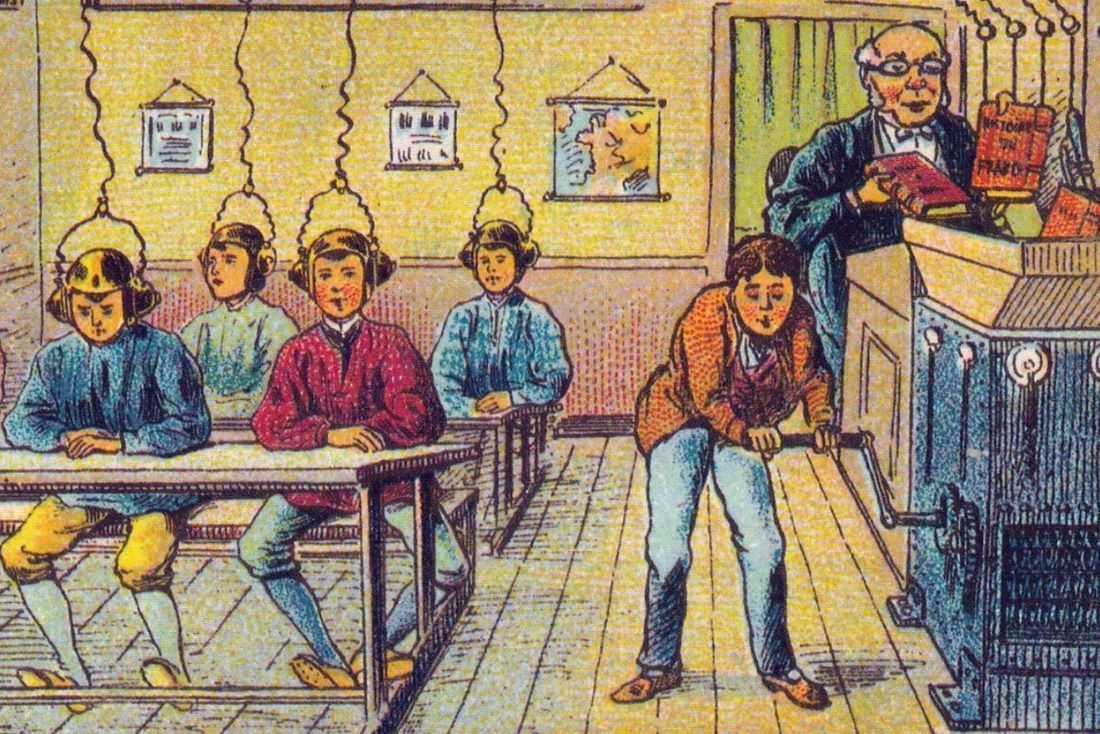

John Dewey was one of 20th century America’s most ardent supporters—and critics—of the schools. He strongly advocated the adoption of teaching methods responsive to the natural curiosity, life experiences, and interests of children, rather than methods promoting passive reception of information. Both public school advocates and home educators frequently cite Dewey as one of their “patron philosophers.” His works Democracy and Education and The School and Society lend strong support to the child-centered forms of education favored by many progressive home educators. Yet he also opposed child-centered approaches that allowed the child to pick-and-choose what he or she should study—an approach that fails to recognize the child’s immaturity. Dewey himself would not likely have favored homeschooling; he was a great believer in the role of social institutions in transforming culture and he gave the school a central place among them.

Schools, however, have and create their own problems, and the need for reform is continuous. Almost everyone recognizes that. During the 1960’s and 1970’s, Harvard professor John Holt became convinced that school systems were unable to be reformed, so he urged parents to take their children’s education into their own hands, thereby founding the modern homeschool movement.

The foregoing history demonstrates the breadth of philosophical reflection concerning education in the West. There is a long history, 23 centuries of history, which Bartholet either ignores or is ignorant of in her attack on homeschooling. As we shall see in the coming section, there is also a rich legal history which deserves consideration.

The American Constitution and Legal Dimensions of Home Education

Just how far may the state go in controlling and regulating education? This question received continuous legal attention throughout the 20th century. Several U.S. Supreme Court cases established the general framework within which American society attempts to balance the interests of parents and the state. The most important was Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925). In 1922 the citizens of Oregon voted into law a requirement that all children attend public schools only. Parents who sent their children to a private school would face a fine and imprisonment (the Ku Klux Klan was a strong supporter of the law). The Oregon law was challenged, and the U.S. Supreme Court held that it “unreasonably interfered with the liberty of parents and guardians to direct the upbringing and education of children under their control.” The Court placed a constitutional limit on the power of the State to standardize its children, stating,

The fundamental theory of liberty upon which all governments in this Union repose excludes any general power of the state to standardize its children by forcing them to accept instruction from public teachers only. The child is not the mere creature of the state; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.

At the same time, the court ruled that the state could compel education including, to some degree, the content of that education. It could not, however, impose a uniform system of beliefs and values on all students. The Pierce case has since become foundational for ensuring parental rights in the education of children.

In Meyer v. Nebraska (1923) the Supreme Court ruled that a Nebraska law prohibiting the teaching of modern foreign languages was unconstitutional in that it interfered with the rights of parents to determine the education of their children. In its opinion the Supreme Court specifically linked the actions of Nebraska’s legislators to Plato’s “Guardians” in the Republic, noting that Plato’s ideas regarding the relation between the individual and the state are entirely different from ideals on which American institutions rest.

A 1973 case involved Old Order Amish families in Wisconsin. The Amish believe children should enter the adult world of Amish society following the 8th grade, and take their place as responsible members of the group. The State of Wisconsin required all students to attend school until age sixteen. The Yoder family refused to do so and were taken to court, fined, and threatened with jail. In Wisconsin v. Yoder (1973) the Supreme Court ruled that parents have the right to determine their children’s education in accordance with their religious belief. It held that the state’s legitimate interest in education,

Is not totally free from a balancing process when it impinges on fundamental rights and interests, such as those specifically protected by the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment, and the traditional interest of parents with respect to the religious upbringing of their children.

The court further recognized that the primary role of parents in the upbringing of their children “is now established beyond debate as an enduring American tradition.” That holding has not ended ongoing controversies, though.

None of these court cases dealt specifically with home education. Their significance lies in establishing a constitutional basis for parents’ rights in guiding their children’s education. Indeed, numerous local, state, and federal cases dealing with home education have drawn on the cases cited above. Bartholet does not find much comfort in the central findings of any of these cases, federal or local, and a reader of her essay gets the sense she would like to have them ignored or overturned.

Subsidiarity and Solidarity: Catholic Social Teaching

In the public mind, home education is often associated with both separatist groups and sectarian tendencies among fundamentalist Christians, and with good reason. A large number of homeschooling parents do withdraw their children from the schools in an effort to isolate them from what they see as the pernicious influence of secular ideologies and immorality in the public schools. Such Christian homeschoolers (some Catholics included) often see themselves as a “remnant”—set aside from the rest of society and the Church—who will transmit the “true” teachings of the Church to the next generation (e.g., Tara Westover’s family). But this need not be so.

Fundamentalists are not the only religious group that homeschools. As already noted, there are Catholic, Jewish, Mormon, Native American, and Muslim home-educators, and these diverse groups do not begin with the same theological presuppositions. Historian Milton Gaither distinguishes two broad categories of modern homeschoolers:

- “closed communion” groups, primarily conservative evangelical Christians who exclude non-Christians and even non-Protestant Christians from membership. Some of these groups require members to sign a “Statement of Faith,” which enumerates the tenets of conservative Evangelicalism; and

- “open communion” groups, which are generally a combination of secular and religious families open to members of all beliefs and no belief.

I will here draw on religious principles from the Roman Catholic tradition as an alternative to both Bartholet’s pleas to ban home education, and to “closed communion” groups. These are the complementary principles of subsidiarity and solidarity, principles that are usually overlooked in discussions of homeschooling. I draw on them because they are especially resonant with the political philosophies discussed previously, and they attempt to balance individual rights with prerogatives of society as a whole and the state. These two principles arose within the tradition of late 19th and 20th century Catholic Social Teaching (CST).

The classic statement on subsidiarity was formulated in 1931:

One should not withdraw from individuals and commit to the community what they can accomplish by their own enterprise and industry. So, too, it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and a disturbance of right order to transfer to the larger and higher collectivity functions which can be performed and provided for by lesser and subordinate bodies. Inasmuch as every social activity should . . . prove a help to members of the body social, it should never destroy or absorb them (Pope Pius XI, Quadragessimo Anno).

How does this apply to homeschooling? Homeschooling, by its very nature, is a local, family enterprise at variance with the centralizing tendencies of state and federal educational bureaucracies. Many religious leaders criticize the tendency of governments to centralize power, to absorb individuals and civic associations, and to direct their energies towards furthering the government’s interests alone. Although the principle of subsidiarity began as a caution against Communist authoritarianism, its application is broad, and has been adopted in secular as well as religious contexts, e.g., the European Union.

A specific element in CST is the central role of the family in directing the education of children. In fact, in Divini Illius Magistri (1929), Pope Pius XI specifically cited the central holding of Pierce v. Society of Sisters as support for that right. In Gaudium et Spes, the Second Vatican Council noted that the State must protect the right of all children to an education and ensure that education is properly suffused throughout society, but “must always keep in mind the principle of subsidiarity so that there is no kind of school monopoly, for this is opposed to the native rights of the human person . . . to the peaceful association of citizens and to the pluralism that exists today in ever so many societies.”

John Paul II says that the right and duty of parents to educate their children is “original and primary with regard to the educational role of others” and can never be entirely delegated to others or usurped by governmental authorities (Familiaris Consortio).

These passages refer to parental rights in education generally, not home education specifically, but some argue that homeschooling families embody the principle of subsidiarity in a unique way. The rights enjoyed under the principle of subsidiarity do not form a one-way street, however. The criticism stems from concern that an increasing number of individuals have no sense of obligation to the larger community. CST emphasizes that the rights of individuals and families protected by the principle of subsidiarity have a corollary duty imposed by the principle of solidarity.

In Catechesi tradendae (1979) John Paul II says that education must not neglect education for an integral liberation: “the search for a society with greater solidarity and fraternity, the fight for justice and the building of peace.” Parents who educate their children at home, then, have the duty to teach principles of social justice and promotion of the common good. They must remain linked in solidarity with the broader church and society and endeavor to promote the general welfare and the improvement of society in whatever way they can.