Łukasz Tischner: Our project “Literature and Religion: Challenges of a Secular Age” refers to the ideas of Charles Taylor. The main concept we borrow from Taylor is, as in the title of his most famous book, “a secular age,” understood not as an age of religion’s decline, but in terms of transformation of a condition of belief—theistic claims are no longer self-evident, must be confronted with non-theistic views. Do we really live in a secular age? What does that mean to you?

Thomas Pavel: Can human history be divided into clearly separated ages, each of them coherent and showing everywhere the same features? I was born in Romania, and in my native country the period between 1948 and 1989 was very, very different from the same period in France or in America. And now, during the second decade of the twenty-first century, being active in both French and American academic life, I see how in these two countries people talk about similar issues, globalism for instance, but they are far from meaning the same thing. Yes, in some countries, at some social levels, there are definite symptoms of secularization. But rather than generalize this tendency to the whole world, we should perhaps think of it in a differentiated way.

Charles Taylor’s book is beautiful and full of insights. Because he has a Hegelian background, Taylor sees history as a series of organic movements, all more or less necessary. But he seems to avoid two features of Hegel’s philosophy of history that are difficult to accept. One is the providential nature of history, which in Hegel’s view embodies the growth and maturation of the World-spirit, in other words, of Hegel’s term for God. Not only whatever happened had to happen, but, quite dramatically, all that happens is rationally justified: the real, Hegel claims, is the rational. The other problematic feature is the philosopher’s absolute certainty that his theory is right.

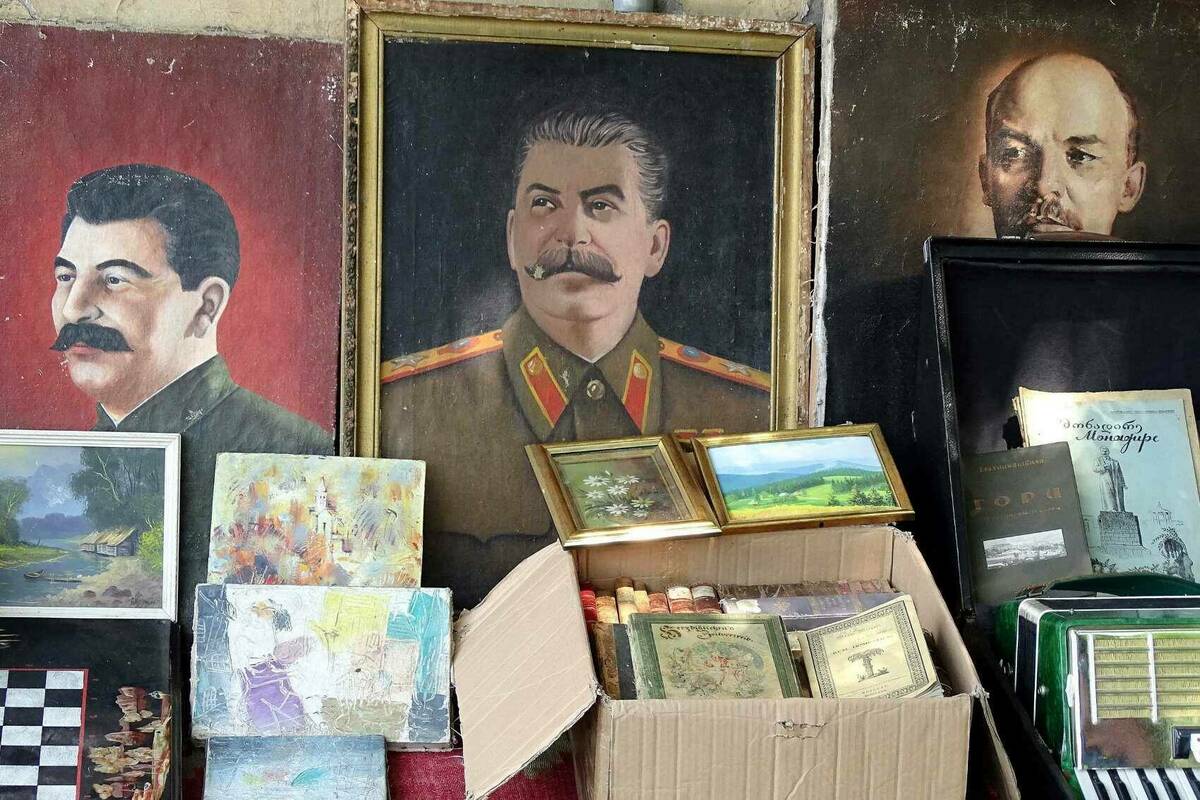

Now, if we rigorously apply these features to the statement according to which we live in a secular age, it would mean first, that the World-historical maturation of the World-spirit inevitably led to secularization, and second, that this diagnostic is absolutely certain. But is it so? The mass-wars invented at the end of the eighteenth-century, the weapons of mass-destruction in the twentieth century, totalitarian political systems all along the twentieth century, and the massacres enacted by these wars and political systems, do they represent the maturation of the World-spirit? Do they provide an absolutely certain proof that the real is rational? Isn’t it rather difficult nowadays to take Hegel at his word? One of the great merits of Taylor’s book is the flexible approach he adopts when he speaks about the present age.

Taylor’s views of society are close to those of Émile Durkheim, one of the most important French sociologists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. According to Durkheim, nations are kept together by organic features that provide them with a more or less coherent way of life. At the same time as Durkheim, another French sociologist, Gabriel Tarde, emphasized an additional dimension of social action and trends. Novelty and changes, Tarde argued, are brought about by people, by smart individuals who trigger imitation. According to him, innovators move things around, generate trends, pushing their milieu, their city, their country ahead. Interestingly enough, if we call these people ‘elite’, the term does not necessarily mean nobility.

The Chicago sociologists whose work in the 1930s and 1940s was inspired by Tarde’s ideas studied gangs, finding that they result from the activity of a few smart guys who mobilize and organize those around them. In a way, what Taylor describes so beautifully represents the present final stage of a long development: in certain countries, in certain milieus, you have indeed a secular age, as a result of its earlier promoters, the smart, influential individuals, who had (or have) this kind of personal attraction and pushed (or push) either for secularism or for opposition to secularism.

Ireneusz Piekarski: Is it not a romantic view: there are some exceptional, charismatic people who have an internal power to move the world? To attract other people?

TP: Up to a certain point yes, but not entirely. The Romantics believed that exceptional people are a gift from Heaven, whereas in the sociology of Tarde these elite people, these leaders, are just individuals or groups who have an idea, an initiative. And they cannot succeed if they are not followed. To win they need imitators. One of the best examples, fashion, is far from being romantic. Some people suddenly start to wear this new kind of hat. A very simple kind of imitation: the way human beings operate.

This approach allows you to seek for these people, especially concerning religious topics, to seek for these people who, when they speak, let’s say, about grace, they know what they are talking about, and they inspire you. Simone Weil, for instance, an incredible woman, one of these smart, influential people, lived mostly alone, because she was too active, too strange for those around her. But when you read what she wrote, you immediately want to follow her, because when she talks, she knows what she is talking about, she is the one who discovers, and we might say, the one who reveals.

ŁT: I understand your reservations about broad Hegelian views on history, but on the other hand, do you feel, that we are living in a secular age as defined by Taylor or do you just reject this description?

TP: How can one reject Charles Taylor admirable description of the present? These two aspects: an age and the individuals who take initiatives and manage to mobilize the other people are complementary. What Taylor calls the “secular age” is a result of human action and interaction. We do not do what we do because we are just shaped by the age in which we live. We do what we do because we are part of groups that adopt certain kinds of ideas, ways of behavior, scales of values. As Taylor shows, during the secular age so many smart people genuinely believe in God and have religious experiences.

And if in some areas of the world (but not everywhere) one can indeed detect a lower participation in religious activities, this is probably related to the rise of prosperity in these particular areas. People need God especially when they suffer. Suffering makes you understand that this world is not all that there is, it does not provide the last word. But as soon as we reach prosperity, to many of us it seems that we do not need anything else. Equally important is the way in which certain aspects of our contemporary prosperity—ads, the internet, instant communication—constantly solicit our attention in so many fields, weakening our inner quiet, such that we would need to take a decisive step back in order to realize that peaceful contemplation is part of our way of being.

ŁT: Maybe I would just add, that for Taylor this secular age is not a natural enemy of religion. For him it is a kind of positive challenge, an opportunity to get rid of, or clean up our approach to religion from everything that is created by our drives, also from political appetites. Some people accuse him of being too optimistic...

TP: Yes, his optimism is beautiful. And his book makes us understand why, when we look around, we see empty churches in some countries (the wealthy ones), waves of religious fanaticism in poor countries, and the rise of religious demagoguery in wounded countries.

IP: The arts and religious experience are inextricably intertwined. In the nineteenth century some thinkers like Matthew Arnold, Arthur Schopenhauer or Friedrich Nietzsche tried to show that the fate of art is ultimately to substitute religion. What is the relation between literature and religion in the twenty-first century?

TP: To achieve mystic perfection, there are at least two things that you should do: first, turn your face away from the world and towards God; second, be an ascetic, fast, pray, refuse worldly pleasures. Modernist art offers a secularized version of this attitude: its works turn away from the world, they do not try to understand and represent it, and, in addition, they make art consumption an ascetic experience, these works being most often very difficult, if not impossible to understand. The typical example is James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. “High art” is supposed to reach this level of sacrality, while accessible works are often looked upon with contempt as mere low, popular art. But why should one despise accessible, non-mystical art? What is wrong with readable books about us, human beings? What if art cannot possibly replace religious experience?

IP: What do you think about Northrop Frye’s perspective, which says that the Bible is the matrix, pattern, and the root for all literature of Western civilization at least? For every age, because under the series of displacements some biblical myths, images, heroes are still present, in disguise, in modern literature. I am asking about it because I found in your books the example of Heliodorus’s Chariclea as a kind of archetype for Pamela or Clarissa.

TP: The idea that certain important literary creations or religious texts would reverberate century after century points to an important aspect of cultural traditions. But is there only one such great work? The Bible is absolutely essential, but so too are the Iliad, the Upanishads, some Eddas. I have just reread the Iliad and it seemed as youthful and frightening as ever. Giambattista Vico distinguished between heroic societies, led by warriors, and civilized societies that depend less on heroism and instead discover monotheism, monogamy, and good manners. While the Iliad is a heroic poem, does The Ethiopian Story by Heliodorus describe the ideal of a civilized society.

IP: Which currents in the Literature and Religion field are still promising today?

TP: Nowadays people use the prefix “post” so often. Terms like postmodernism, post-humanism, post-colonialism, are asking us to stop looking at the past, to consider it gone, gone forever, worthy of being forgotten. But why should one forget it? It seems to me that what we see around us is a multiplicity of competing trends, some new and some old, that in art and literature we live in a pluralist landscape, still having the avant-garde (few people outside the university read it, but we still have it) and also enjoying multiple layers of literature, some venerable, some innovative, some popular, some tastefully refined.

IP: Do you have preferred tools to study literature, or favorite currents in criticism?

TP: Form and style are wonderful, construction is wonderful, but when I read a novel, what I want to know is what happens. Specialists in narrative discourse appreciate the free indirect style in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. I read Madame Bovary because I want to see what this poor woman would do. She makes lots of mistakes by choosing undeserving lovers, she buys expensive clothes and she ends up having huge debts. What fascinates me in this novel, in any novel, is the plot, the characters, the reasons why they do certain things, their intentions and their moral sense. Literature succeeds if it arouses the interest of readers, if it speaks to their hearts.

IP: Can we call it humanistic criticism?

TP: I do not know how to call it. I appreciate my colleagues in narratology who pay attention to content, while also being careful about the art of narration. More recently some literary critics became interested in empathy. Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1790) inspires them, as do Theodore Lipps and Max Scheler. In a book on the history of the novel (The Lives of the Novel) I tried to describe the links between human beings, action, and the ideals that guide them.

ŁT: Can you name some currents in the field of Literature and Religion, some people, who bring real contribution to such studies?

TP: I dare have some reservations about hermeneutics. Specialists in hermeneutics begin by deciding what they want to detect in a work and then they look for it. I would rather be interested in a more spontaneous, more naive reading. Friedrich Schleiermacher, the founder of hermeneutics, first resolved: I have the Bible, I have Luther. You, Bible, you should say exactly what Luther said and, to be sure, I will make you say it. But what if the Bible did not necessarily want to say what Luther, much later, said? We are faced with the same problem in the case of overly political interpretations of literature: critics are under the obligation to make various literary works argue what these critics or the trends to which they belong decide they must argue. Would it not be better to find out what literature herself tells us, to listen to it? And if we are interested in its religious message, to listen to religiously-oriented works? One of my favorite writers is Paul Claudel, a deeply religious French poet: I just listen to what he tells us.

ŁT: To do justice to hermeneutics, one should mention some masterful interpretations by Gadamer or Ricoeur, which do not lead to expected conclusions—like Gadamer’s reading of Paul Celan, for example.

TP: You should read or attend a performance of Rodogune, one of the best plays by Pierre Corneille. It stages the conflict between two ancient queens, one from Syria, the other one from Persia. In such cases, Paul Ricoeur instructs you first to think about the situation in the Middle East during the first or the second century, then look at the play, compare it with the moral rules in your own modern times, pay attention to the differences also.

But what if you get the point of the play before any historical or comparative efforts? What if there is something in us that resonates with literature wherever it comes from? As soon as we begin to witness the action, we get it: two passionate women who fight against each other. Yes, these women are queens from Syria and from Persia, but to understand their jealousy and rivalry one does not need to consult Ancient history. Sometimes specialists in hermeneutics remain too academic. They do not realize that literature goes directly to you and resonates directly inside you. Listen and let your heart resonate.

ŁT: It is Jürgen Habermas, who coined the term ”post-secular,” after the World Trade Center terrorist attack in 2001. You will probably express a reservation, but do you pay attention to so-called post-secular studies? Is it a significant contribution to contemporary human sciences?

TP: If this kind of studies called it “Ways of remembering or thinking about God” it might be better. Why should we think that what happened last night dramatically cuts us off from the past? What goes on today is a mixture of long-term traditions, of recent initiatives, of successes and failures.

IP: So, is your position in any way similar to Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht? He talks about presence, Stimmung, the reading of moods. And he is also anti-hermeneutic.

TP: I truly admire Gumbrecht’s work. To be more precise, it seems to me that in contemporary culture, three very important elements must be taken into account. First, we should not forget. Present-day education and culture ask us to forget the past: you are from Poland, from Romania, from France, it does not matter, who cares? We live in a global system, you need to forget. Second, we should resist the dispersion of attention. Nowadays at every moment tens of messages relentlessly fight to capture our eyes and our brain. We need to resist. Third, we should not accept that everything has to be useful. Day and night we are told that utility is the final criterion, but Charles Taylor’s refutation of utilitarianism in Sources of the Self: The Making of Modern Identity showed us how mistaken this claim is. These three elements of the present day education and culture—everything has to be useful, disperse your attention and forget the past—go against our deep need to concentrate, to remember and to contemplate.

IP: But is not dispersion of attention a feature or aim of modern literature, like Joyce, for example?

TP: Joyce’s work, a beautiful monument of modernism seen as religion of art, bets on it. Do you know the work of Josef Pieper? He is a calm, extraordinarily perceptive twentieth-century Thomist philosopher, as close as possible to Aristotle. At least one of his short and substantial books should be required reading: Leisure: The Basis of Culture in which he distinguishes between the culture of work, present in Immanuel Kant’s idea that “philosophy is working hard”, and the culture of leisure and contemplation. I would also recommend his anthology The Human Wisdom of Saint Thomas, a selection of non-theological fragments from Aquinas about human life. Here is one of his most memorable quotations from Aquinas: “The first source to which every act of the will is reduced is that which is willed naturally by man.” Naturally.

ŁT: We will now concentrate more on the issues you work on. Should literature and religious studies consider a perspective of the moral-existential orientation of protagonists, that is, their recognition of constitutive goods, of the good life? Or can religious issues be studied separately from ethical problems?

TP: We cannot separate them. Because you mentioned “existentialm” let me point out that, in addition to Simone Weil, I deeply admire the philosophy of Gabriel Marcel. Among all the existentialists he is the one who does not build grand systems like Heidegger and, instead of emphasizing human loneliness, the way Sartre does, is sensitive to our openness, to our availability to other human beings.

It seems to me that the link between the moral message and the religion of a writer is a crucial issue: you should not hide the fact that Balzac was a Catholic. He had some strange ideas as well, but he was a Catholic, and Dickens was a deep believer.

ŁT: What I mean is inspired by Charles Taylor and his concept of fullness. The term refers to his philosophy of the good and is defined as a general sense people have of what it means to live a good or fully human life. Fullness is something you aspire to. For him it is a term that may establish common ground for believers and unbelievers.

TP: Again, Charles Taylor is such a wonderful optimist, he should have lived in Eastern Europe. His statements describe a most important literary tradition. In studying the history of the novel I realized that literature can either over-idealize the human condition or severely denigrate it. Over-idealization shows us in which direction, towards which ideal we should aspire. And, at its limits, like in Heliodorus, this ideal makes us sense the presence of the Divinity. It is somehow there, irradiating light and hope. But there is also the other literature, which emphasizes our fallen nature, our imperfection: the picaresque novels, the novels about crooks and swindlers, stories that make you laugh or make you shudder. And the two can be combined, in the way in which, in Defoe’s novel Moll Flanders is a whore and a thief but in the end she converts, becoming a good Christian.

ŁT: Crime and Punishment is another example.

TP: Crime and Punishment is even more serious, it is one of the novels in which Dostoyevsky describes so well the demonic side of our culture. For those who adopt this side, the ideal is not fullness. What counts is to declare as many human beings as possible your inferiors and to crush them.

ŁT: Taylor’s perspective is that everyone somehow aspires to fullness. He also mentions that you can sense this fullness in a negative way, as something that you are desperately lacking.

TP: Should we, however, forget that something demonic, something devilish exists both in the world and in our hearts? And that we have to be very, very strong not to be led into temptation?

ŁT: But Taylor is fully aware of the horrors of the twentieth-century and refers to René Girard’s scapegoat mechanism and the concept of a radical evil in this context. In his A Catholic Modernity? and some interviews he admits, that nowadays it is not only fullness but also a perverse, unjustifiable evil, that brings to mind religious questions.

TP: Twentieth century dictatorships reminded us that by turning away from God, one invites the devil. The sense, even the silent, blind sense, that there is something higher keeps one from completely falling in.

ŁT: I don’t know whether you read My Century (Mój wiek) by Aleksander Wat, where he says that: “It is hard to believe in God in the twentieth century, but it is even harder not to believe in the devil.”

TP: He is so right. Because he lived in the 1930s and later, he saw the demonic faces of the twentieth century whose threat Dostoyevsky had predicted. On this topic the Bible is simple and precise. The most terrible sin, according to Genesis, is to want to be like God. But let us say that Ludwig Feuerbach, Hegel’s disciple who influenced Marx, was right. Who is God? The human projection, he says, of human features. Why should these projections, he then asked, be exiled in the Heavens of myth? Let us bring them back, he concluded, on Earth, among us. No, Herr Feuerbach, we should say, let us not do that! Let us not bring them back! It was a fabulous idea to put these human features at a distance, to project them far away, because as soon as you bring them back, you not only try to recover (perhaps) human perfection, you also, for sure, bring back our demonic side. Let the projection of both our perfection and our demonic features stay there, in the heights, forever. Religion, even if it were just a human projection, should be carefully preserved. Even if you are a disciple of Feuerbach and believe that God is an invention, beware of destroying it.

IP: You once said that “The logic of counterfactuals seemed to me to account for a fundamental intuition, that according to which the world could have been different, that other worlds are possible, that our world, as it is, is not absolutely necessary in each of its detail, nor is it the only possible one: possible worlds logic thus pleases those who like freedom, religion, and literature”. Why?

TP: We have to come back to what we talked about at the very beginning. We need a sense that this world is not all there is, that this world does not provide the last word. If you say “what is here is the last word,” you become either unbearably self-righteous or desperate beyond redemption. And you leave little space for grace, for transcendence, for imagination. You are fully caught in the realm of necessity. Certainly, religion teaches some things that are rather incredible and some of them may be rooted in fantasy, but there is nothing wrong with that. It is just a way of not being completely stuck in the realm of necessity. There is something else.

IP: So imagination is also a kind of religious organ?

TP: The imagination is an organ on which one can play religious music. And it is not by chance that we, humans, are both creatures of imagination and religious creatures.

ŁT: In your paper “Fiction and Imitation” you said:

Rather than imitations, Antigone’s predicament, Pompey’s fall, Amadis de Gaul’s energy, Don Quixote’s folly, Mary Stuart’s despair and dignity, Fleur-de-Marie’s flawlessness, Anna Karenina’s mindless love are puzzling examples of the unpredictable bonds between humans and the norms and values that govern their existence. These examples bring our mind to bear upon such unobservable things as the majesty of the ideals, the opacity of the world, and the operation of freedom.

Does this majesty of ideals originate somehow in religion? It is quite striking that in Genesis of Values by Hans Joas ethical investigation is parallel to philosophy of religion.

TP: Hans Joas’s book was and still is for me a major source of inspiration. The main function of our mind or our soul (you can use either term) consists in recognizing values and ideals. I often reread Meno by Plato, a dialogue during which a young, illiterate slave is led by Socrates to recognize the truth of the theorem of Pythagoras as present in his own mind. There are things that we have never learnt, yet we recognize. Our religious life is based on the same type of recognition. Yes, we say, this is how it is, we are built this way. There is something in us that resonates with ideals and recognizes them as ours. The recognition of ideals belongs to the same family as the recognition of the religious appeal.

IP: Towards the end of The Lives of the Novel you write: “The lives of the novel have one thing in common, the bid to make the ideal visible within a world of transitory, fragile, imperfect human actions”. Is the novel somehow privileged as a mirror, grasping human endeavors to search for the invisible? Can it be interpreted in religious terms?

TP: I wanted to end the book with a spectacular sentence. But I hope that its religious tone is perceptible, because this is precisely the part of our inner being that resonates with the ideal. This kind of resonance is not exactly the same thing as observing life around us, because when we observe life what we mostly focus on its imperfection. We are between what Pascal calls “la grandeur et la misère,” greatness and misery, and we vibrate and recognize both of them but we understand imperfection as such only because of our indelible remembrance of perfection.

IP: And the novel, as a tool, is better than lyric poem or drama?

TP: All plot-based literature works this way. It is true about novels, dramas, movies, epic poems. But for novels, and now movies, it is perhaps a little bit truer. They offer more variety. There are many, many novels, many movies, much more than the works in other genres. This is what people do: read novels and watch movies.

IP And some are playing role-playing games.

TP: Yes, in the same way.

ŁT: Why are you so attracted by strong souls? Is it because they have confident religious beliefs and openly cooperate with Providence (contrary to “enigmatic psyches”)?

TP: In The Lives of the Novel I tried to emphasize, polemically, the importance of this tradition, from Heliodorus to the seventeenth century, of long idealist novels that few people still read and to the nineteenth and twentieth-century popular literature, Les Misérables by Victor Hugo, The Lord of the Rings by Tolkien. Polemically, because according to some critics the rise of the novel is only linked to comic literature. Comic works had certainly an impact, but they were not the only factor.

ŁT: Coming back to strong souls, why did you intend to value this tradition?.

TP: The tradition of depicting strong souls coexisted with the tradition of making fun of human beings. Robert Louis Stevenson, the great Scottish author of adventure novels, polemicized with Henry James, who thought that literature should be as close as possible to reality, to the extent of becoming a rival of reality. Stevenson answered that literature needs to exaggerate, and he is right, literature exaggerates, either human grandeur or human misery.

IP: Does the worldview of the interpreter somehow affect interpretation? If so, does it produce great dangers? Are they inevitable? Can they be minimized?

TP: Certainly, and this is why it is so important to listen to literature, to try to find out what the author and the work say, not what you would like them to say. If at the end of King Lear you say: “I, born in Romania, who witnessed persecution and destruction, I think . . .” your statement is not crucial. What is important is what Shakespeare’s play tells you.

IP: Is it possible to free ourselves from presuppositions? To be just a critic, without a denominational label?

TP: Rather than giving advice to critics, perhaps we should advise readers, suggesting, for instance, that, first and foremost, they would be well advised to pay attention to the books they read, to listen to them, try to vibrate, to resonate to what literary works tell us.

IP: In 1931 the Polish philosopher Roman Ingarden, in order to describe the aim of fiction in real life, wrote about metaphysical qualities (tragic, dreadful, sublime) evoked by the fictional worlds, qualities we can contemplate and deal with as long as we want and whenever we want (and qualities not so strong as in real life). His proposition, it seems, is similar to Jonathan Lear’s conclusion that thanks to fiction “We imaginatively live life to the full but we risk nothing.” Is this the sense of fiction? To evoke metaphysical qualities, feelings. Thanks to literature we are “safely watching wild adventures” as in the title of one of your last papers.

TP: Yes, these qualities are essential—thank you for mentioning Roman Ingarden, one of the greatest thinkers of the last century, as well as my respected colleague Jonathan Lear.

ŁT: In our project we raise the hypothesis (probably quite obvious) that contemporary religious views are affected by World War II, the Holocaust, and the gulags. We think that it is also mirrored in the literature after the Second World War. To what extent have Auschwitz and Kolyma shaped religious aspects of contemporary literature? Do you find these determinants relevant?

TP: Yes, the Holocaust and the gulags, as well as what happened in Poland and in Ukraine on both sides. It is a very difficult question, because during the period you mentioned our demonic side was in charge of large areas of our planet. Both Communists and Nazis rejected God and divinized our species. We saw the consequences. The writers who describe them the best are those who remain as understated as possible. This is why Vasily Grossman’s novella about the Ukraine famine triggered by Stalin (Everything Flows) is so moving: the author does not impose any conclusion, he just shows us how human beings can turn out to be.

ŁT: He has the incredible gift of empathy.

TP: Yes, empathy, but just without over-emphasizing it at any point. As for the Holocaust literature, I don’t know enough about it because I just cannot bear to read it.

ŁT: I think for example of Primo Levi.

TP: At some point I will manage to read his work. What makes the literature about the communist gulag a little bit less unbearable for me—I love Varlam Shalamov, for instance—is that it describes a savagery that did not claim to be biologically scientific. You read the old sagas and find the same primitive cruelty, except that communists expanded it immensely. What is so terrifying about the Holocaust is its systematic, bio-technological aspect. And yet the Nazis did not know anything “scientific” about Jewish or Slavic people. It was just their desire, bestial-human desire to be both savage and technologically competent. And this bodes ill for the future, given that technology grows exponentially and savagery is still around us.

As for the links between religion and political terror, let me recall the stories of two Romanians I knew well, who were arbitrarily arrested during the wave of anti-intellectual terror of the early 1960s. One of them, from Transylvania, was a very religious Byzantine Catholic. Put in prison he lost his faith. The second, a Jewish intellectual and a good friend of my parents, was asked to be a witness of the persecution in a political trial against a group of intellectuals, all of them his friends. Because he refused, he was arrested and condemned for fourteen years of prison for . . . being a Nazi. In prison, he converted and was secretly baptized. Two entirely different experiences: terror can empty you but can also give you this fullness that Charles Taylor talks about.

ŁT: In addition to “a secular age,” we can use other descriptions: “an epoch of the eclipse of God,” or, “the age of religious homelessness for many.” What would be the literary work crucial to understanding the religious anxieties of our time?

TP: Novels usually talk about things that happen just next to us, they are about parents, children, love; they look at the closest circle around us and, through it, they sometimes let us see rays coming from Divinity. Do writers who try to write on this topic, manage to do it well? I recall Ida, a Polish movie, I saw a of couple years ago. Its director admirably captured the post-Stalinist atmosphere of the mid-to-late 1950s, during the first liberalization.

Young Ida’s aunt, a powerful communist prosecutor, had lost her important job and survived as a second tier judicial bureaucrat. Without going into all details of this beautiful movie, let me just mention the music—not the ideas, the music. In the final scene, when young Ida, who, having decided to devote her life to Christ, feels happy and free, we hear a Bach theme: Jesu, joy of man’s desiring (played by Alfred Brendel). And when her aunt, the former Stalinist prosecutor, decides to put an end to her life, she switches on a vinyl record which plays the beginning of the Jupiter symphony by Mozart (Symphony no. 41). Jupiter, the pagan god.

ŁT: What are you currently working on?

TP: The title of my next book will be How to Listen to Literature. You already know its content: our whole conversation was about it. Thank you so much for your wonderful questions.

EDITORIAL NOTE: A version of this interview has appeared in Literatura a religia: wyzwania epoki świeckiej, Tom 1: Teorie i metody, eds. Ł. Tischner, Ł. Garbol (Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, Kraków 2020).