By now, we have grown so familiar with the technological lament that we are tempted to register it as noise. We read exposés of big tech by Timothy Wu and Nicholas Carr, and hear about Silicon Valley execs so wary of their own creations that they send their kids to screen-free schools. These are satisfying sentiments to hear, but none of them stems the creep of screens into every crevice of our lives. We pass our waking hours in a scatter-brained haze, bouncing from work emails to tweets to personal messages in a state that can only be called addiction.

In her journalistic memoir Attention: A Love Story, Casey Schwartz participates in the technological lament, but the personal nature of her reflections allows her contribution to achieve something that The Shallows and The Attention Merchants cannot. Starting with her own addiction to Adderall and proceeding to investigate modern attempts to regain our lost attention, she plumbs the existential questions that underlie our collective escape into our screens. When we willingly cede our focus to Silicon Valley, she wonders, what is it that we are fleeing? What about the present moment makes it inadequate to the demands of our attention?

Christian contemplative prayer asks the same questions. The tradition that stretches from the Desert Fathers through the Spanish Mystics to Thomas Merton unites itself around the practice of silent prayer, which aims at, in Evelyn Underhill’s words, “the art of union with Reality.” Contemplation constantly calls our attention to the present moment to uncover the divine presence which animates it. Though Schwartz does not address the contemplative tradition directly in her book, she connects with it tangentially through her fascination with someone heavily influenced by it: the twentieth century thinker Simone Weil. Drawn to Weil’s insight that “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity,” Schwartz is not content to situate attention inside the self; instead, she insists on the necessary link between attention and our moral obligations to others. In doing so her book opens a space for dialogue with the Christian mystical tradition.

Schwartz begins her story with her addiction to Adderall, which started during her time as an undergraduate at Brown and continued for a dozen years. Like many who came to depend on the stimulant during the early 2000s, her use began not with a prescription for ADHD but with the desire to accomplish more tasks. Widely sold and traded among students at the time, Adderall offered Schwartz the chance to become “rapturously, singularly, focused.” As her addiction deepened, however, the drug seemed increasingly toxic to her life. She recounts panic attacks, the unnerving “waxy” feeling of her senses when high, and her difficulty engaging in the deep thinking that she valued as a writer and intellectual. Over the years her dependence on Adderall also damaged or severed close relationships. Despite its destructive effects, Schwartz presents the drug as an entirely rational choice. For a world that demands our frenetic, flickering attention, something like Adderall makes perfect sense.

Her addiction provides a point of departure for her investigation into cultural attention post-smartphone: “In the same way that Adderall . . . [had] divested us of our actual powers of attention, so too had our technology come to make life feel more overwhelming, not less.” Most of us would concur—and yet we continue to embrace technology, grown accustomed to our discontent with it. Cognizant of the paradoxical relationship most of us have with our technology, and the intractability of its presence, Schwartz does not engage in a culture-war against our screens. Rather, she explores the dimensions of our relationship, confident that “everyone knows it’s about something else, way down.”

Schwartz’s search for answers starts with David Foster Wallace, who, perhaps more than any other modern fiction writer, wrestled with the question of what it means to pay attention. In his well-known 2003 commencement address at Kenyon College, “This is Water,” he equates our everyday failures of empathy—like getting annoyed at slow checkout lines and aggressive drivers—with failures of imagination:

If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.

These may sound like poetic ideals, but Wallace’s instructions are quite practical. We can choose what to focus on, and the more we pay attention to others—here, by imagining what they are going through—the more we decenter the self. Schwartz concurs, and throughout the memoir she measures the quality of attention by its ability to make us more cognizant of the needs of others.

The recent resurgence of interest in psychedelics proves fruitful for Schwartz’s investigation. Like the initial spike of psychedelic use in the 1960s, the epicenter of this renaissance is San Francisco. Now though, instead of tripping to the Grateful Dead in Haight Ashbury, adherents “microdose” at their Silicon Valley jobs, consuming very small amounts of hallucinogens like LSD or psilocybin to heighten perception and increase productivity. Others treat PTSD or depression with trace amounts of MDMA (Ecstasy).

At a convention in California, Schwartz encounters a tightly-knit yet eclectic mix of psychedelic users. Though centered on “sober speeches and Power Point presentations,” the gathering had the “raucous, joyful spirit of a like-minded community seeking refuge.” Despite cultish overtones to the group, she comes to respect their experiences: drugs genuinely have provided them respite from what LSD pioneer Stanislav Grof called the “spiritual emergency” of our modern, isolated existence.

Along with addiction specialist Dr. Gabor Maté, Schwartz attends a posh retreat in Central America where participants ingest Ayahuasca, a mythical plant once sought out by William Burroughs for its hallucinogenic properties. The plant offers the promise of a transcendent vision in which the soul, according to the retreat owner, reunites with its lost childhood innocence. The plant’s effects are purgative, and large quantities of bodily fluids are expelled during the ritual.

Schwartz does not participate, but observes the process with a mixture of fascination, compassion, and even envy. The retreat-goers genuinely seek healing, and though a few go away disappointed, many do experience such a vision as promised. In the end, the effect of the author’s foray into the psychedelic renaissance is not to advocate for it so much as to humanize it. If it is true, as Gabor Maté says, that “we live in a culture that makes people sick,” doesn’t it make sense to try to get healthy? In other words, why not psychedelics?

Schwartz examines the life of Aldous Huxley to shed light on this question. After publishing Brave New World the author became interested in religious mysticism, and started experimenting with LSD and mescaline. Huxley grew more and more fascinated with achieving deep attention through psychedelics, which he explained in his 1954 book The Doors of Perception.

Just before he died (on the same day as John F. Kennedy), his last request was to be injected with LSD. Among his final remarks: “It is never enough. Never enough. Never enough of beauty. Never enough of love. Never enough of life.” Schwartz emphasizes these lines to convey the insatiability of the entire psychedelic movement, driven by its quest to obtain relief from our contemporary wasteland, to capture the ever-elusive peace.

What does this all have to do with contemplation? A correspondence between Huxley and a young Thomas Merton, mentioned but largely unexplored by Schwartz, provides an answer. As an undergraduate at Columbia in the late 1930s, Merton was greatly influenced by Huxley’s writing on ethics and politics. After he became a Trappist monk, he continued to read Huxley, and when his writing took a turn towards psychedelics, the monk, by then a well-known author himself, wrote him a letter raising questions about using drugs to achieve altered states of consciousness.

“Are we not endangering the whole conception of mystical experience in saying that it is something that can be produced by a drug?,” Merton asked. Huxley’s response, which cited the beneficial effects of psychedelics, did not satisfy him. The monk’s final opinion on drug use is best expressed in a passage from Zen and the Birds of Appetite, one of the last books published before his sudden death in 1968:

Drugs have appeared as a deus ex machina to enable the self-aware Cartesian consciousness to extend its awareness of itself while seemingly getting out of itself. In other words, drugs have provided the self-conscious self with a substitute for metaphysical and mystical self-transcendence.

Contemplation cannot come in a pill, or a plant, Merton suggests, because these do not require the hard work of detachment from self. Contemplation is not simply a state of mind to be achieved, in his words, from the “casual use of a material instrument.”

Merton’s point speaks to the complex relationship between our contemporary fascination with mindfulness and the tradition of contemplative prayer. Mindfulness is a notoriously vague term, but in general it implies an effort to achieve tranquility of mind by living more fully in the present moment, attentive to thoughts and physical sensations. On the surface, mindfulness bears great resemblance to contemplation. Both involve gradually stilling the discursive mind, paying attention to rhythms of the body, and using something concrete (in contemplative prayer it is often a repeated word or phrase) to rein in the unruly intellect.

Their goals are different, however. Mindfulness aims to achieve mental tranquility; contemplation aims for no less than “union with Reality,” to use Underhill’s phrase. A reduction in mental distractions is a common benefit of contemplative practice, but it is not the goal. In fact, contemplation often demands that the practitioner accepts distractions in prayer, and even grows comfortable with them, rather than trying to eliminate them. The anonymous fourteenth-century author of The Cloud of Unknowing encourages us to live with distractions, as if looking over their shoulder to where “God is hidden in the dark cloud of unknowing.” Aiming only for freedom from distraction—that is, for pure attention—falls short of genuine contemplation, as it tethers success and failure to our own desired outcomes. As such, mindfulness reinforces the self at the center of the spiritual project, whereas the goal of contemplative prayer is the opposite.

Compare this contemplative understanding of attention to that of David Foster Wallace. In “This is Water,” he equates a failure to attend to the reality of others with a failure of imagination:

You can choose to look differently at this fat, dead-eyed, over-made-up lady who just screamed at her kid in the checkout line. Maybe she’s not usually like this. Maybe she’s been up three straight nights holding the hand of a husband who is dying of bone cancer. Or maybe this very lady is the low-wage clerk at the motor vehicle department, who just yesterday helped your spouse resolve a horrific, infuriating, red-tape problem through some small act of bureaucratic kindness. Of course, none of this is likely, but it’s also not impossible. It just depends what you want to consider.

Attention to others, for Wallace, is a willed creative act. If we can imagine other people’s stories, we can empathize with them. We are self-centered by default, but thinking in this way, Wallace suggests, makes us other-centered.

Wallace’s exercise, though perhaps effective at detaching us from some of our selfish qualities, depends, in the end, on ourselves. It presupposes our ability to imagine our way out of our conundrum into a deeper connection with others. Contemplation asks us to reconsider the terms of engagement: to be completely open to reality, we must deny our will in all things, especially our imagination. "Attention,” Weil claims in Gravity and Grace “is bound up not with the will but with desire.” Imagination has no part in contemplative prayer because it is the chief way in which the will interposes itself between us and what is real. A vibrant imagination is no doubt part of a well-rounded spirituality (St. Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises rely on it heavily) but in contemplative prayer it is an obstacle. Weil is blunt on this point: “We must continually suspend the work of the imagination filling the void within ourselves.” To confront reality, we must detach ourselves even from our own thoughts.

The apophatic strain in Christian contemplation, which informed Weil greatly, emphasizes the unknowable nature of God. As silent prayer brings the practitioner closer to reality, that reality appears increasingly silent itself. Fr. Martin Laird, in his exceptional introduction to contemplation, Into the Silent Land, explains this paradox: “We enter into the land of silence by the silence of surrender, and there is no map of the silence that is surrender.” Weil calls this silence, quite simply, the “void.”

In the final chapters of her book, Schwartz turns to Weil, particularly to her line that “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” With that phrase, Schwartz claims, “Weil elevated attention outside of the self.” Schwartz is wrong here—the Christian mystics elevated attention to such a level long before Weil came along. She was simply bringing the wisdom of the Desert Fathers to the present day.

The French thinker lived a life on the extremes—she was rigidly philosophical, paradoxically religious (though intensely Christian in belief, she refused baptism), and she died at the age of 34 from a combination of illness and self-induced starvation. Despite the radical differences in their lives, the non-religious Schwartz finds herself more intrigued by Weil than she is by either Wallace or Huxley.

To understand Weil’s thoughts on attention and its moral dimensions, one must grapple with Christianity—both in the way she lived out her peculiar faith and in the mystical tradition in which she wrote. Though Schwartz calls herself “hopelessly secular,” she admits that she is “jealous of the capacity to believe as Weil believed.” Because Schwartz is honest and unafraid of difficult questions, her investigation brings her to the intersection of attention and faith. “To pay attention is to believe that there is something worth paying attention to,” she writes at the conclusion of her discussion of Weil, “even if you don’t yet know of what it consists.”

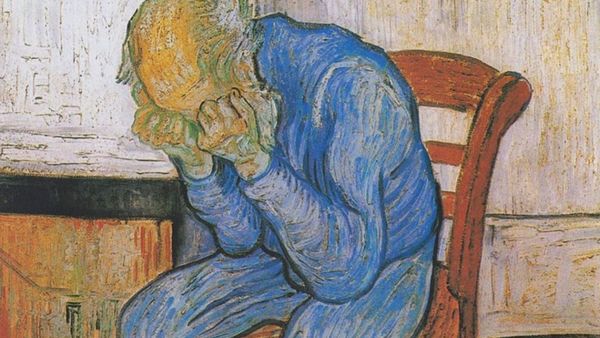

Schwartz’s thoughtful reflections suggest that without faith in something beyond ourselves, attention threatens to turn into attachment to a certain feeling or state of mind. To see this, we need look no further than the stark differences in the deaths of Huxley and Weil. Huxley died asking for more LSD, saying “Never enough”; Weil died from malnutrition in a British hospital because, while already ill, she refused to take more food than what was rationed to those living under German occupation in her beloved France. Schwartz’s book demands that we look closely at these two ways of paying attention. Though we are programmed to focus on ourselves, attention, understood in light of the Christian mystical tradition, invites us to push ever outward.