EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is excerpted from Political Consequences of Crony Capitalism inside Russia (ND Press, 2011). It is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. You can read our excerpts from this collaboration here. All rights reserved.

Popular attitudes toward the government in Russia experienced a rollercoaster ride, reaching the heights of euphoria and hope in the new president in the early 1990s and then rapidly descending into distrust, cynicism, and apathy to the government by 1995 and, even more pronouncedly by 1999, and, finally, finding new hope and rising to new heights starting in 2000, with the election of yet another new president. Below, I first focus on the evolution of popular attitudes toward Russia’s political system, reviewing how Russian citizens viewed their two presidents, country’s political regime, political parties, elections, and democracy in general.

After assessing the political aspect of popular attitudes, I turn to the issue of corruption and evaluate the dynamics of public perceptions of corruption in Russia. Finally, I suggest an interpretation of the data presented in the context of changing political competition levels in Russia and advance an explanation for Putin’s unwavering popularity with the masses.

How Do Russians View Their Presidents?

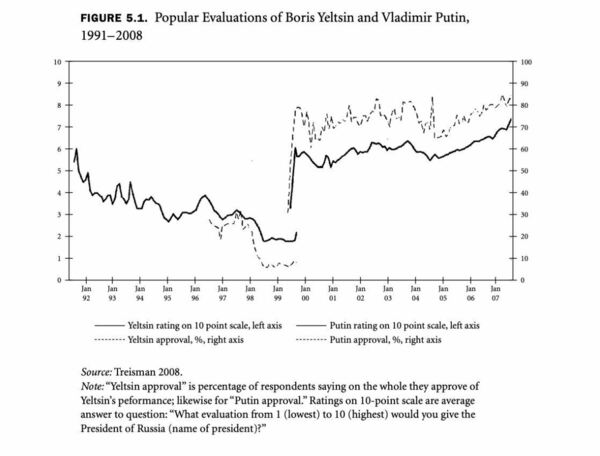

A charismatic politician, Yeltsin was elected Russia’s president on June 12, 1991, at the height of his popularity, as a leader advocating more radical political and economic reforms and representing a real alternative to a more hesitant and cautious Gorbachev. The euphoric period did not last long, however; starting in 1992 Yeltsin’s popularity started to decline. It plunged to single digits by January 1996, when the second presidential elections were held. Only through the efforts of the entire state apparatus and the richest oligarchs, who mobilized their massive financial and media resources behind the incumbent, was Yeltsin able to win in that 1996 race. His second term did not bring him much public support. Seriously ill, he had to withdraw from day-to-day administration and governance, only making abrupt appearances to change personnel and reshuffle the cabinet. Yeltsin’s popularity hit rock bottom in 1998 following the devaluation of the ruble and remained there until the end of his presidency. By 1999 his political weakness was so pronounced that the nation was saturated with frequent rumors about his resignation.

The negative attitudes were reflected even in the polls after Yeltsin’s dramatic resignation on December 31, 2000. Evaluating the historical impact of Yeltsin’s era on Russia, 67 percent of respondents in January 2001 (right after Yeltsin’s decision to resign) thought that it was more negative than positive, and only 15 percent assessed his era as positive. The dynamics of popular approval for Russia’s second president caused much controversy. Putin, practically unknown to the public until his appointment as prime minister in August 1999, rapidly garnered popular support as a result of his tough stance on the Chechnya issue and maintained remarkably high approval ratings since his election as president in March 2000. Putin was unscathed by events potentially very damaging to his popularity, with his approval ratings remaining at 70 to 80 percent, creating what became known as “the Putin phenomenon.”

The level of support for Putin was not affected by the loss of the submarine Kursk, airplane crashes, or the tragedies of Nord-Ost and Beslan. On the contrary. Some pollsters observed that after such cataclysms Putin’s ratings went up, leading some observers to comment on Russia as a country of masochists. Indeed, Putin was able to maintain such remarkable high ratings until the end of his term in 2008 and even after that, as Russia’s prime minister, economic crisis notwithstanding.

Public Attitudes toward the Regime, Political Parties, and Elections

The discussion of the dynamics of regime approval in Russia is informed in this section by the work done by the Center for Study of Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde. The New Russia Barometer (NRB) survey, conducted in Russia by the respected Levada Center, has traced popular attitudes toward the Russian regime since 1992. The dynamics of regime approval reveal the relatively low rating for the Yeltsin regime in 1992–99 (ranging from a low of 14 in 1992 to a high of 38 in 1996, when measured on the scale from negative 100 to positive 100) and the steadily rising approval rating under Putin, starting in 2000 (from 37 in 2000 to 65 in 2004). Those with negative perceptions of the regime had always outnumbered positive evaluations throughout Yeltsin’s era. Under Putin, this situation changed as a majority of Russians seemed to endorse the regime.

While the public evaluation of the regime has shifted in Russia, distrust of political parties has not changed. Political parties have consistently been among the most distrusted institutions in Russia throughout Yeltsin’s and Putin’s eras. Only 9 percent of respondents expressed trust in political parties after the parliamentary elections in 1999, while 75 percent actively distrusted them. By 2001 the number of people trusting parties was about 6 percent. Apparently, Putin’s presidency has not brought any change in this realm. Despite the resources channeled to United Russia, public distrust for political parties did not lessen and United Russia’s membership grew more because of the administrative resources mobilized by political elites than because of ideological party believers. The high degree of public distrust of parties in Russia is reasonable. Over the 1990s political parties became the favorite item in the political technologists’ toolbox and were actively used for manipulating electoral outcomes.

The spurts of political creativity around election times led to the emergence of “scarecrow” parties frightening the electorate (as the Communists were presented in the 1996 presidential elections), “neophytes” exploiting public disillusionment with politics and using an outsider status, “false aerodrome” parties created to fail and divert criticism, spoiler parties to steal votes from the real competitors. Clearly, political parties in Russia have not become an institution aggregating and representing various societal interests in accordance with democratic theory. They are rather instruments for “managing” electoral outcomes and promoting specific politicians. Putin has not been able to change the skeptical view of political parties in Russia; in fact, he has probably reinforced it by refusing to join any party. Even his decision to lead United Russia when he became prime minister under President Dmitry Medvedev did not cause him to become a member.

While distrust for political parties has been pervasive and consistent over the 1990s, public attitudes have revealed a negative trend in regard to another democratic institution in Russia, namely, elections. In the early 1990s numerous surveys indicated high levels of support for competitive elections. However, already by 1996–97 researchers had noted that this support was declining. The Russian public’s faith in the electoral process continued to erode subsequently, as is clearly reflected in the change of perceptions about the need for elections. By 2003–4 the number of people favoring the cancellation of elections had sharply increased. This trend was also manifested in the indifference among the public when Putin abolished gubernatorial elections. Not only that people did not protest that their rights were abrogated, but surveys demonstrated a growing number of people approving this decision. More respondents approved of Putin than disapproved in regard to the abolition of gubernatorial elections. Russian pollsters have pointed out that the tendency for elections to become devalued among the public continued after 2003.

How Do Russians View Democracy?

The opinion polls studying public attitudes toward democracy in Russia have produced contradictory evidence. This is to be expected: given the wide divergence of views in academic circles as to what constitutes a democracy, the complexity of popular perceptions of this term could be anticipated. Most opinion polls reveal that Russians have valued and still favor democratic ideals and principles. However, more recent polls show a certain shift in the regime type preferred for Russia. When asked in 1998 a general question about an ideal regime for Russia, most respondents preferred their country be a democracy, not a dictatorship. In recent years the survey results have been more conflicting. Some of Russia’s polling agencies increasingly talk about popular disaffection with democracy and a shift in preferences toward more authoritarian forms of government. Thus in 2005, 51 percent of respondents thought that Russia needs a president-dictator. Echoing this popular mood, some analysts suggested that the 2008 elections would bring to power a president similar to Lukashenka, president of Belarus, and Nazarbayev, president of Kazakhstan, both well-known authoritarian leaders in post-Soviet Russia. Other pollsters have found that a majority of Russians still reject all authoritarian alternatives and prefer a democratic regime.

An understanding of such contradictions is not possible if we do not inquire into the popular meaning of democracy in Russia. Specifically, what do Russians view as necessary for the government to be democratic? The NRB survey shows that people widely agree that democracy must involve the rule of law (“equality of all citizens before the law”), multiparty elections, and economic welfare. Given the absence of the rule of law and widespread economic welfare, it is not surprising that most Russians do not view Russia as fully democratic; most place it somewhere at the midpoint between democracy and dictatorship. At the same time, it could also have been expected that if the system of the 1990s was in fact associated with democracy, then such an association could have given democracy a bad name for the majority of Russians. Therefore, these contradictory findings of the opinion polls—some suggesting that Russians still support democracy and others pointing to shifting preferences—might all be reflecting the same thing: people support a more ideally understood concept of democracy (when it is coupled with a functioning state and the rule of law) but reject its deformed implementation in the 1990s.

The Dynamics of Corruption Perceptions

Earlier in Political Consequences of Crony Capitalism Inside Russia I discussed the changing nature of corruption in Russia. Was this difference reflected in the subjective evaluations of corruption in Russia? Even more important, was the declining political competitiveness under Putin paralleled by lessening public perceptions of corruption, as could be expected from the argument advanced in this book?

The most systematic assessment of corruption perceptions in Russia (as in many other countries) is done by Transparency International, a leading international organization that conducts regular surveys to assess the level of corruption in countries around the world. TI data allow for tracing corruption perceptions in Russia in the period from 1996 to 2008. The pattern that stands out is largely supportive of the argument about the impact of political competition under crony capitalism, especially for the period 1996–2004. The TI data demonstrate that in the period 1996–2000, under the more competitive regime of Boris Yeltsin, there was an identifiable negative trend of increasing perceptions of corruption (from 2.6 to 2.1). This trend then reversed in the first term of Putin’s presidency. During 2001–4 public perceptions of corruption declined from 2.1 to 2.8. Hence Russia nationwide reveals a trend similar to that found in its regions: greater competitiveness seems to be associated with higher perceptions of corruption, while a more controlled public space and restricted opposition under Putin produced, at least in the first four years of Putin’s presidency, decreasing subjective evaluations of corruption by the people.

Even further, the TI data arguably allow for establishing a direct link between the most intense electoral campaigns and the resultant public views on corruption in Russia. Indeed, if information wars and negative campaigns have a direct impact on corruption perceptions, then it could be expected that there would be a sharp rise in corruption perceptions following the most intense 1999 electoral season in Russia. The TI data confirm this by a more substantive, three-decimal-point drop (from 2.4 to 2.1) in the index of corruption perceptions in 2000, whereas the previous three years were characterized by a relative stability (2.3–2.4) in subjective evaluations of corruption.

However, contrary to my expectations, this trend seems to have reversed in 2005, which stands out as a year in which the TI assessment of corruption perceptions in Russia fell sharply, from 2.8 to 2.4 (bringing Russia from 90th place in 2004 to the lowest-ever 126th place, which it shared with Niger, Albania, and Sierra Leone). Furthermore, after slightly rising in 2006, Russia’s ranking in corruption perceptions continued to drop in 2007–8. It appears that the early Putin years of more positive evaluations of the corruption situation in Russia have given way to more skeptical views. How can this shift be explained?

One potential explanation might be found in the studies done by the INDEM foundation, a Russia-based nongovernmental think tank. In their report “The Diagnostics of Corruption in Russia: 2001–2005,” INDEM scholars noted, among other things, that the economic growth and increasing prosperity in Russia were paralleled by an increase in bribes: the average bribe size in 2005 was thirteen times higher than in 2001. Various other commentators have also noted that as the economy grew in the 2000s, the amount of resources flowing in the informal sector skyrocketed.

It appears plausible to suggest that Russia’s sliding position in TI rankings on corruption perceptions since 2005 might reflect the fact that popular perceptions of corruption started to catch up with the reported dramatic increase in corruption and especially in the amount of bribes given out in real life in Russia. A quick look at the methodology used by TI further clarifies this puzzle. To produce the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) indices, TI relies on evaluations done by country experts and business leaders, who are likely to be much more aware of the real situation and trends in the extent of corruption plaguing a country. These assessments therefore might differ significantly from popular views on corruption levels in Russia. Indeed, Stephen White and Ian McAllister, who have conducted studies on how ordinary people in Russia perceive corruption levels, report that popular perceptions of corruption under Putin have in fact been decreasing despite the fact that real corruption levels have reportedly grown.

Connecting the Dots: Cronyism, Competition, and the Puzzle of Putin’s Popularity

To the question, “What do you think is the biggest obstacle to Russia becoming a normal society,” a majority of Russians (66 percent) responded government corruption and nonenforcement of laws. The Putin phenomenon and the unwavering public support enjoyed by Russia’s second president should be understood in the context of how Russian citizens view the major problems plaguing their state and society. Russia’s authoritarian turn under Putin is not an unexpected and annoying detour from the democratic path that Russia had been following before he came to power. It originates from the fissures that had developed in the crony capitalist institutional order during the 1990s. Specifically, it is a counterreaction to the destabilizing dynamics of the competitive, oligarchic system that has emerged in Russia during the 1990s.

The manipulative tools and technologies used by political and economic elites during the much-publicized struggles for power and property brought the issue of corruption to the surface, undermining public faith in the state, political institutions, and the ruling elites. By the late 1990s a new political momentum rose in Russia. It was characterized by the demand for a new “political formula” if the political authorities were to maintain control. Putin reacted “adequately” to this new political context. Unable (and unwilling) to root out crony capitalism, he restricted political competition and power struggles, thus removing the main “trigger” undermining public faith in state institutions and the political regime, and focused on recovering (first of all in public eyes) the public purpose of the state. This, I argue, is the primary reason for his lasting popularity and consistently high and robust approval ratings that have puzzled numerous analysts.

Stability, order, and economic growth are claimed to be among the primary achievements of Putin, whose leadership is perceived to be based on a philosophy combining reform and order and the pursuit of centralization for the sake of modernization. However, if one looks into what was really required for that stability to be attained, then the most conspicuous policies of the new president were related to the elimination of freedom of the press in the country. The rowdy 1990s were replaced by the tightly controlled official media featuring self-congratulatory reports and constant adulation of the president, including sometimes even his dog. The new media situation along with other important changes implemented by Putin for integrating the regional elites and the oligarchs into a centralized pyramid of power (vertikal’ vlasti) and propping the political regime with a strong party of power produced a new political context that promoted feelings of greater stability and order among the public.

Of course, several consecutive years of economic growth under Putin were another essential ingredient of Russia’s newly found stability. It has been debated whether any of Putin’s economic policies contributed to this growth or whether it is associated mostly with the currency devaluation following the August 1998 financial crisis and high oil prices. Indeed, the initial economic growth is likely to have originated from the boost given to the domestic producers by the ruble devaluation in 1998 and supported by high oil prices. Persisting until 2008, high oil prices benefited Russia’s economy and society enormously by contributing not only to enlarging the state coffers and enabling new national projects but also to raising personal incomes and bettering the living standards of ordinary people, which, in turn, boosted the retail, construction, and real estate sectors of the economy.

At the same time, it seems reasonable to suggest that Putin’s early economic policies such as reducing tax levels, increasing fiscal transparency (for regional budgets, for example) and promoting financial sovereignty (paying off the previous debts the country had) could have had a lasting positive effect on the economy as well. Therefore, Putin’s popularity might also reflect people’s appreciation of this newly found economic prosperity. Indeed, Treisman has argued that public perceptions of economic well-being are the single most important factor explaining presidential popularity in Russia. He claimed that Putin’s popularity is a direct reflection of Russia’s economic success in the 2000s.

This argument has not withstood the test of the recent economic crisis, which hit Russia hard. Russia’s stock market has lost around 70 percent of its peak value, amounting to the worst performance among the emerging markets. The economic crisis has also led to a sharp drop in incomes and rising unemployment levels. The socioeconomic situation became especially dire in Russia’s numerous mono-cities (i.e., those built around a single enterprise) as well as the capital city of Moscow, where economic activity (specifically industrial production and construction) fell by around 30 percent in the first nine months of 2009. If anything, it is such a crisis that, according to Treisman’s argument, would have tarnished Putin and his successor Medvedev’s popularity.

But Putin’s amazing popularity has not been substantially affected. According to Levada Center reports, Putin’s popularity between May 2008 and May 2009 fluctuated between 76 and 88 percent (of those respondents who approve of Putin), and Medvedev’s popularity has followed Putin’s very closely. These numbers demonstrate very clearly that popular perceptions of the economic situation could not have been the single most important factor in determining presidential popularity in Russia. Rather, I would argue, it is the regime’s control of the media and its conditioning effect on public perceptions combined with the absence of publicly available political alternatives to this regime that are responsible for the continuing popularity of Putin and his political formula for Russia.

Conclusion

The analysis of political dynamics under Russia’s two presidents provides solid support for the argument advanced in my book Political Consequences of Crony Capitalism Inside Russia about the impact of political competition under crony capitalism. In light of this argument, the authoritarian turn and political consolidation in Putin’s Russia are best understood as a reasonable response by the Russian political elite to the problems and challenges that emerged under Yeltsin’s competitive crony system. Putin broke away from the vicious cycle of rival elites clashing over state power and undermining the legitimacy of state authorities and political institutions in the process of these clashes. Without publicized elite rivalries being played out during electoral campaigns or over privatization issues, the state could engage in a systematic “convincing and explaining” of the main party line to the public. With full control over the media and in the absence of challenges from outside the political establishment, the authorities could employ propaganda tools effectively and create a deferential public that would not be frustrated with the conflicting information coming from rival information channels.

The elimination of political competition in Russia removed only the fact that cronyism is explicit. Russia remains a crony system and is therefore fundamentally weak and vulnerable. Its longevity hinges, first, on the degree of elite integration and co-optation into the system and, second, on the resuming of the economic success that characterized Putin’s presidency. If the regime is not successful in integrating the elites and managing covert conflicts, the cracks and cleavages in the system can lead to an onset of another round of open political competition, repeating the pattern of the 1990s. Similarly, if people feel further impoverished as the economic crisis continues or do not feel appropriate attention from the government to their concerns, propaganda tools employed by the regime are likely to fail, and destabilization of the system becomes more likely. Thus continuing attention to the party of power for uniting the elites as well as national social projects for promoting the people-friendly image of the regime are likely to be crucial for the continuation of Russia’s political regime headed, after the 2008 presidential elections, by Putin and Medvedev.