The Oxford Movement is often associated with scholarly men, particularly John Henry Newman and Edward Bouverie Pusey, but also John Keble, Richard Froude, and Robert Wilberforce, all of whom were fellows of Oriel College, Oxford. We also tend to think of those responsible for the Tracts for the Times—known as the “Tractarians.”

While it is true that most of the central texts of the Oxford Movement were composed by men, the movement itself was not devoid of female voices. It can even be argued that the reception of the movement was in fact more female than male. Nineteenth-century Anglicanism experienced a gender imbalance in which women made up the majority of those present in congregations, and it was often at the hands of women that the church functioned on a day-to-day basis, both financially and practically. Women were often the ones physically present for the sermons and passing along the High-Church message to their peers. To put it bluntly, the pastoral nature of the Oxford Movement would not have been so successful without the women, who were most of those subject to the pastoring. These women also sought (as well as gave) spiritual and theological advice, kept the churches running, and disseminated the message of the Oxford Movement to their friends. Because of this, historians today must look carefully at how women were involved in and influenced by the Oxford Movement if we are to gauge the reach of the Oxford Movement more fully within the context of the greater Anglo-Catholic movement of the nineteenth century.

Introduced here are women who were deeply influenced by Newman particularly, as well as by the greater Oxford Movement. These three women had varying degrees of interaction with Newman personally. The first is Newman’s mother, Jemima Newman, who was one of his greatest supporters in his ministry at Littlemore. As a beloved member of his family, Newman cared deeply for his mother, as he did also for his Aunt Elizabeth and sisters. The second, Mary Holmes, was a governess and musicologist to whom Newman provided spiritual direction at the height of the Oxford Movement, though the friendship would continue until her death in 1878. The final person discussed here is poet Christina Rossetti, who never corresponded directly with Newman, though she was quite influenced by Newman’s writings and the greater Oxford Movement’s ethos and body of literature, particularly after the movement had spread to London. Because of her stature as a published poet and relationship with the Pre-Raphaelites, much more scholarship exists on her life, what influenced her, and her work itself.

Jemima Newman

Some of the most intimate correspondence between John Henry and his mother is witnessed in their letters concerning the people and church at Littlemore. In these letters we see the development of Newman’s pastoral opinion of how the parish ought to be run, as well as his growing enthusiasm for his responsibilities to his lower-middle-class parishioners. At the beginning of his tenure at the parish of St. Mary the Virgin—which originally included the people of Littlemore, who were located a couple of miles from Oxford City Centre—Newman would spend the vast majority of his time at Oriel and St. Mary the Virgin Church, while the people of Littlemore, who were without a chapel at the time, were often an afterthought.

At the consistent encouragement of his mother, Newman would come to realize that the people of Littlemore had their own distinctive needs, which led to his founding the chapel of Saint Mary and Saint Nicholas, as well as a school in the Oxford suburb. Many of the letters exchanged between Newman and his mother at this time explained these particular needs, such as a governess to teach the children and someone to make sure the children had proper clothing and combed hair for Easter Sunday. Newman became deeply involved in the life of Littlemore and would eventually prefer it over the hustle and bustle of academic life in Oxford. Writing to his mother and sister, both named Jemima, Newman would eventually say how he wished he could spend all his time in Littlemore because he had become quite fond of the people, particularly the children.[1]

Much of what Newman did for the people of Littlemore was at the encouragement of his mother. In a letter dated 26 June 1836 Newman reminisced on his relationship with his mother shortly after her death about which he said, “I can never repent it for the good she has done to Littlemore.”[2] Newman dedicated the chapel he built at Littlemore to his mother, and we can observe the monument at St. Mary and St. Nicholas church still today.

Mary Holmes

Mary Hester Holmes (1815–1878) was a convert to Tractarianism who eventually converted to Roman Catholicism in 1844, the year before Newman’s conversion. She was a published musicologist and governess, who corresponded frequently with the likes of Anthony Trollope, William Makepeace Thackeray, and of course John Henry Newman. Her upbringing encouraged her to become proficient in literature and languages, including French, German, and Latin. Mary Holmes was never married and tended to change jobs frequently, which as her correspondence with Newman demonstrates, caused both her and Newman trepidation at times. Holmes inquired with Newman about help in publishing her first book, Aunt Elinor’s Lectures on Architecture, Dedicated to the Ladies of England (1843), which reflected the Tractarian interest in Gothic church architecture, as opposed to the neoclassical style common to England at the time. This would not be Mary Holmes’s sole publication.

From May 1850 until January 1851, the Lady’s Newspaper and Pictorial Times of London featured a series of Holmes’s articles entitled, “A Few Words about Music.” These articles were signed only by her initials “M.H.” In 1851, these articles were expanded into a book entitled, A Few Words about Music: Containing Hints to Amateur Pianists; to Which Is Added a Slight Historical Sketch of the Rise and Progress of the Art of Music, published by J. Alfred Novello. Like the newspaper articles before, Holmes published these articles under her initials M.H. As Christine Kyprianides discusses in her article, “A Few Words about Miss Mary Holmes,” despite Holmes’s accomplishments, she remains an elusive figure for historians. This is in part due to a cataloging error, which attributed her publications to a “Mrs. Hullah,” rather than Miss Holmes. It took nearly a century to notice this clerical error, and the error is still in place in many locations, as can be seen in the link directly above.

What was the nature of Holmes’s and Newman’s relationship?

Mary Holmes initiated correspondence with Newman in 1840 due to her growing interest in the Oxford Movement. Their correspondence quickly became almost daily, and sometimes even multiple letters per day, for the subsequent four years. Holmes and Newman did not meet in person until two years into their friendship, though by the time they physically met they were well acquainted with one another.

Their letters were often cordial, especially at first, though Newman became frustrated with Mary in the months leading up to her conversion to the Roman Church because Newman advised her against conversion and implored her to wait. Newman’s main source of frustration, aside from Mary’s conversion, was that she sought spiritual direction from both Newman and a Roman Catholic priest simultaneously. Sometimes comparing the advice, Mary followed the path in which she thought God was leading her, even though it caused some friction between herself and Newman.

The frustration that Newman felt toward Mary eased upon her conversion, and there is even an air of admiration in Newman’s tone as he wrote to Mary after his own conversion to Catholicism in 1845. While the letters after Mary’s conversion became less frequent, they remained friends until her death in 1878. Much of their correspondence is theological, in which they discuss the sacraments and the differences between Protestantism and Catholicism. They also discussed architecture and liturgy, even the minutiae of liturgical performance and theology. Newman’s admiration for Mary Holmes likely led to his decision to transcribe the series of letters under the title, “The History of a Conversion to the Catholic Faith: In the Years 1840–1844.”

What spiritually or theologically drew Holmes to Newman?

As Mary Holmes’s interest in the Oxford Movement grew, she would eventually ask Newman to become her spiritual director. While Newman destroyed the more confidential letters exchanged between the two to preserve Miss Holmes’s privacy, in 1863 he transcribed the extant letters into a single document as a way to preserve the story of her conversion, though he did not attach her name to it to maintain the confidential nature of their letters. The significance of this transcription, and what Newman seems to have wanted to preserve, is how Miss Holmes went from an interest in Anglo-Catholicism to Roman Catholicism. Holmes converted prior to Newman’s own conversion, and what is preserved in this series of transcribed letters is how she came to understand various doctrines from a Roman perspective, such as the communion of saints and transubstantiation. Felt in these letters on the part of both Newman and Holmes is an excitement for her faith transformation. Newman also expresses his feelings of betrayal when she speaks of conversion to the Roman Church, though this would be forgiven once she had actually converted, and Newman would even later agree conversion was the right decision after his own conversion to the Roman Church. We also experience in these letters doubt and frustration and joy from both Newman and Holmes as her spiritual journey unfolds.

My reason for describing this exchange in these broad strokes, rather than the minutia of her doctrinal exploration, is to demonstrate what Newman had invested in this woman whom he only met a handful of times in person. He cared deeply for her opinions and displayed an openness to her observations that we do not see in all his correspondences.

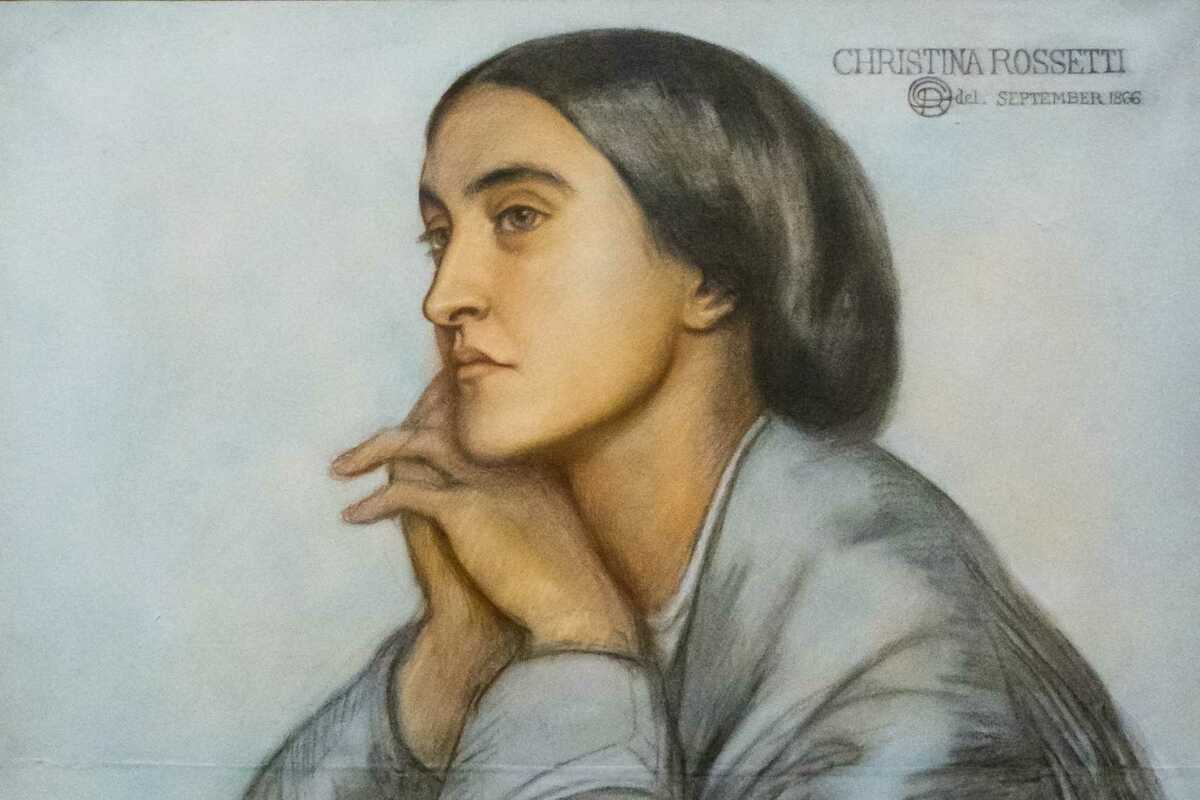

Christina Rossetti

Christina Georgina Rossetti was an English Romantic author and poet. Her major publications include “Goblin Market” and “Remember.” Her widest-reaching and best-remembered poem today is a Christmas carol by the title “In the Bleak Midwinter,” which was later set to music by Gustav Holst.

Christina Rossetti is the sister of poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, along with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais. Christina Rossetti is featured in many of her brother’s paintings and was intimately involved with the Brotherhood. A combination of her own publications along with her ties to the Pre-Raphaelites led to her fame, though her life was far from simple.

Beginning early in life, Rossetti would suffer from bouts of depression. She had a nervous breakdown at the age of fourteen, which led to her leaving school and returning home. It was during these bouts of depression in her teenage years that Rossetti became engrossed in the Anglo-Catholic movement sweeping the Church of England at the time, the Oxford Movement being one of the most well-known of this Anglo-Catholic movement.

Rossetti spent her life in London, where she attended Christ Church, Albany Street, which is known as the leading church of the Oxford Movement once the movement had spread to London. Along with her sister, Maria, Rossetti supported many Anglican sisterhoods, including The Society of All Saints, of which Maria would become a fully professed sister in 1876. Rossetti’s regular religious devotional practices were encouraged by members of the Oxford Movement (such as confession and receiving Holy Communion) would play a major role in her life and writings.

How was Rossetti influenced by the Oxford Movement?

Noted in the introduction to the 1925 edition of Rossetti’s Verses is that “Her [Christina Rossetti’s] religious views were Tractarian, that is to say, Anglo-Catholic without any leaning toward Roman Catholicism and strongly Puritan.”[3] Found in her private library are copies of Keble’s Christian Year, which she carefully illustrated herself, as well as Isaac Williams’s The Altar.[4] Rossetti held the writings of Isaac Williams in special esteem during the last years of her life, and in 1892 as she convalesced from cancer surgery, she enjoyed having her brother read from the Autobiography of Isaac Williams.[5]

Elizabeth Ludlow demonstrates how

Tractarianism informed the early Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic and how Rossetti took this aesthetic forward and, in turn, used it to inform and disseminate Anglo-Catholic theology, contributing to the maturing of the Movement’s theology rather than being simply an [and I quote from Tennyson] “inheritor of the Tractarian devotional mode in poetry.”[6]

This dissemination is demonstrated when, as Ludlow explains, “a number of her poems appeared in seminal Anglo-Catholic anthologies,” particularly, Orby Shipley’s Lyrica Mystica: Hymns and Verses on Sacred Subjects (published in 1865) and Lyrica Eucharistica: Hymns and Verse on the Holy Communion (1864).

Much of Rossetti’s religious poetry can be seen as a typological depiction of “the church as a space prepared for an experience of divine revelation.”[7] This is seen prevalently in the final lines of her unpublished poem “Yet a Little While”:

We have clear call of daily bells,

A dimness where the anthems are,

A chancel vault of sky and star,

A thunder if the organ swells:

Alas our daily life—what else?—

Is not in tune with daily bellsYou have deep pause betwixt the chimes

Of earth and heaven, a patient pause

Yet glad with rest by certain laws:

You look and long: while oftentimes

Precursive flush of morning chimes

And air vibrates with coming chimes.[8]

According to James Pereiro, much of the ethos of the Oxford Movement “considered religion and poetry closely related, for God has used poetical language to communicate himself to man, employing symbolical associations—whether poetical, moral, or mystical—to reveal a world beyond sense perception.”[9] This interplay between the earthly and the mystical can be seen in these lines of Rossetti’s poem.

How was Rossetti influenced by Newman’s writings in particular?

Christina Rossetti owned a copy of Newman’s Dream of Gerontius and admired Newman’s life and work, particularly his more poetic works.[10] Her poem, aptly entitled, “Cardinal Newman,” which was published on 16 August 1890, in honor of his death, demonstrates her admonition for Newman.

O weary Champion of the Cross, lie still:

Sleep thou at length the all-embracing sleep:

Long was thy sowing-day, rest now and reap:

Thy fast was long, feast now thy spirit’s fill.

Yea take thy fill of love, because thy will

Chose love not in the shallows but the deep:

Thy tides were spring-tides, set against the neap

Of calmer souls: thy flood rebuked their rill.

Now night has come to thee—please God, of rest:

So some time must it come to every man;

To first and last, where many last are first.

Now fixed and finished thine eternal plan,

Thy best has done its best, thy worst its worst:

Thy best its best, please God, thy best is its best.[11]

Many of the themes present in her poetry demonstrate the importance of aesthetics for our experience and understanding of the Christian experience, which are themes also found in the work of John Henry Newman, particularly within his Parochial and Plain Sermons. While Newman and Rossetti never physically crossed paths, it is important to note how Newman indirectly influenced her thought.

Conclusion

This article is only a small part of a much larger project that seeks to understand the female reception of the Oxford Movement. Represented here are three “profiles” or “categories” of influence. The first are the women family members of the core participants of the Oxford Movement. Represented here by Jemima Newman, John Henry Newman’s mother, these women can be sisters, aunts, wives, daughters, in-laws, or even grandmothers. The second category, represented here by Mary Holmes, features those who were contemporaries of the Tractarians and had direct contact, but who were not family. As we see in the case of Mary Holmes, these women are often drawn to the movement for spiritual or theological reasons, and they sometimes sought spiritual direction or theological or religious advice from the Tractarians. The third category, represented here by Christina Rossetti, are both contemporaries and later generations of women who were influenced by the Tractarians, but who were never correspondents. The published authors, such as Christina Rossetti, Edith Stein, Sara Coleridge, and Maisie Ward to name just a few, are the easiest to study because the source materials are plentiful and easily attainable, and we are able to trace elements of influence within their published works.

More difficult to study, however, are those women in the pews, silently listening to the Tractarian sermons and perhaps discussing the contents with their friends, or those reading the Tracts and allowed the preaching to influence the way they conducted their lives and the lives of their families. The source material for these women are often personal journals, letters, and parish registries and notes from parish council meetings, etc., which are often more difficult to track down, though the work is necessary to comprehend the nature of the Oxford Movement and its reception history more fully. The motivations of these women, who often made up the vast majority of those physically present in Anglo-Catholic parishes in the nineteenth century, are a major key to understanding what the Oxford Movement really was and how influential the movement was in its own day, as well as in the subsequent decades.

Editorial Note: This article was originally published in the National Institute for Newman Studies’ Newman Review.

[1] This becomes a frequent sentiment beginning around 1840. See LD vii.

[2] LD v, 314.

[3] Diane D’Amico and David A. Kent, “Rossetti and the Tractarians,” Victorian Poetry 44, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 93.

[4] See Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Christina Rossetti and Illustration: A Publishing History (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2002).

[5] D’Amico and Kent, “Rossetti and the Tractarians,” 93.

[6] Elizabeth Ludlow, “Christina Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelites,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Oxford Movement, ed. Stewart J. Brown, Peter B. Nockles, and James Pereiro (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 427–38.

[7] Ludlow, “Christina Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelites,” 434.

[8] Quoted in Ludlow, “Christina Rossetti and the Oxford Movement,” 434.

[9] James Periero, ‘Ethos’ and the Oxford Movement: At the Heart of Tractarianism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 98.

[10] See Rebecca Rainof, “Victorians in Purgatory: Newman’s Poetics of Conciliation and the Afterlife of the Oxford Movement,” Victorian Poetry 51, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 227–47.

[11] Christina Rosetti, “Cardinal Newman,” in New Poems by Christina Rossetti, hitherto unpublished or uncollected (New York: Macmillan, 1896), 261–62.