Responding to the protests for Black lives, Dr. Rob McCann, President and CEO of Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington made a video calling upon the Catholic Church in the region and the organization he leads to face their complicity with racism. At the heart of his message was his recognition that the Catholic Church, Catholic schools, and affiliated organizations, even while calling for a just social order, organize themselves around the comfort of whites and the protection of white society.

The negative responses to McCann only confirmed his point. On July 5, 2020, the Catholic bishop of Spokane, Washington, Most Rev. Thomas Daly, felt compelled to respond because, he said, “Many faithful Catholics, whose lives evidence a daily commitment to compassion and justice, expressed their disappointment and frustration with Dr. McCann’s message.” Bishop Daly wrote,

BLM [Black Lives Matter] is in conflict with Church teaching regarding marriage, family and the sanctity of life. Moreover, it is disturbing that BLM had not vocally condemned the recent violence that has torn apart so many cities. Its silence has not gone unheard.

The bishop’s pronouncement that BLM and Catholic doctrine are in conflict was strange for several reasons.

With decentralized leadership and diverse affiliation, “Black Lives Matter” is a movement, not an organization. Furthermore, BLM’s central message appears to be in harmony with Catholic convictions of the sanctity of human life. So why would “faithful Catholics” and their bishop see the need to distance Catholicism from BLM?

Kurtis Robinson, President of the NAACP in Spokane, connected the local church’s response to the ongoing operation of the “doctrine of discovery,” the religious justifications and legal structures that gave Europeans the right to violently separate indigenous people from their land. He said:

It’s no surprise they’re having a hard time coming to terms with it . . . They’ve been so saturated and permeated with that, and many times don’t see anything wrong with it. That’s the dilemma.

Robinson recognized that the same actions that subjugated indigenous people organized the church’s identity around a white polity.

I grew up near Spokane, in the Palouse region of the northwest. On the Palouse, the first Catholic permanent residents were American Indians. White Catholic settlers who later arrived in this region often worshiped in churches built by indigenous hands. Mirroring the legal processes that transferred land from American Indians to whites, the Catholic Church’s territorial boundaries would be transferred from the Indian missions to that of dioceses and parishes. The church I was raised in was built on land once part of Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) territory.

It was established for white settlers as the attention of the clergy shifted from serving Nimiipuu Catholics on the reservation to constructing a white Catholicism in the nearby off-reservation town. The white church, as Robinson recognizes, was established within the framework of a settler colonialism that organized society around whiteness. This is why its lack of solidarity with Blacks is no surprise. The local church’s stance toward racial justice is consistent with its history and it exposes the operation of a lived ecclesiology.

The Whiteness of the Church

American ecclesial identity is shaped by, and continues to operate out of, a matrix of whiteness. Whiteness refers to the constellation of processes by which a distinct group is accepted as white. Whiteness was constituted through slavery and colonization but is sustained today by “racial capitalism,” that is, systemic conditions that continue to perpetuate the transfer of resources from one group to another. Race is not something someone is; race is something done to one group of people by another group. The “color line” is not natural or stable; it is fluid and something that must be continually remade.

Whiteness was produced and can only be sustained by the processes that reinforce dominance and marginalization, that is, processes that “racialize.” To racialize means to confer race upon another. Persistent systemic inequality forms the means of racialization through economic policy, police impunity, housing, access to medical care, and myriad other conditions. In the face of horrifying incidents of racism, like the recent killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis (May 25, 2020) and Breonna Taylor in Louisville (March 13, 2020) at the hands of police, it is easy to see only the immediate effects of racism—the victims of violence, grieving families, and traumatized communities—and overlook how violence continually establishes the border between whiteness and its others. In the words of Achille Mbembe, whiteness is a “way of anchoring and affirming power” in white bodies and at the same time excluding the “Remainder,” that is, “the dissimilar” and “empty” being.[1]

For Christians, it is too easy to point exteriorly to the racist conditions of society. But racialization also occurs within the Church, both in its theological articulations and in the patterns of human relationship modeled within it. Willie Jennings explains, we live in a “history in which the Christian theological imagination was woven into processes of colonial dominance.”[2] In the United States, Christian theology and white supremacy have historically been entwined.

American exceptionalism, which prioritizes white Anglo-Saxon identity, and Manifest Destiny, which destines white people to the land, are secularized versions of God’s calling of a people and God’s providence over the people of Israel. Christian identity and whiteness intersect within America’s “racial projects” to establish an ideology of white Christian supremacy.[3]

Not only have racial ideas and Christian theological ideas been entangled, but whiteness has oriented the patterns of relationship belonging within the Body of Christ. Cyprian Davis, OSB, the historian of Black Catholicism, called for theologians to interrogate not only the ideas about the Church and salvation, but also the living ecclesiology and soteriology expressed historically in the Church. He asked, what does it mean theologically that,

A slave had to have his owner’s permission to receive communion? What kind of sacramental theology did we have in this country when it was the regular practice in much of the southern United States for white Catholics to receive communion first and Blacks to receive last?[4]

We might add, what ecclesiology did the Maryland Jesuits hold when they sold 272 slaves in order to keep Georgetown University’s doors open? Or—what might strike the heart of a dominant narrative of American Catholicism—what is the theological implication that, for waves of European immigrants, the Church served as an institution key to their racialization, their transformation from Catholics of various European ethnicities into American whites?

The practices of the Church possess an ontological density; they reveal its identity. In catechesis and education, in sacramental life and prayer, in the formation of a people, in charitable work, and involvement in wider society, there is a set of practices that anchor the Church’s identity and structure its relationship to the outside. What if these practices served to inscribe whiteness into ecclesial life?

The United States Catholic Church, for most of its history, was openly racist, segregationist, and prioritized whiteness as the chief form of belonging. Since the civil rights movements of the 1950s to 1960s, there has been a shift in teaching and practices toward addressing structural inequalities and white privilege and moving toward models of multicultural inclusion. But as Katie Walker Grimes explains, describing racism as white privilege fails to attend to how whites are not simply “complicit” with social inequalities that benefit them. White subjectivity itself is shaped by anti-blackness.[5] This is why models of inclusion in the US Catholic Church tend to dissolve into the inclusion of all (non-white) people in the (white) church.

I once attended a gathering of Black Catholic theologians attended by a prominent white archbishop, who was invited to give brief remarks. He appealed to St. Paul’s “many parts, one body” (1 Cor. 12:12)—each part is different and has something unique to contribute to the whole—as an image for cultural diversity within the Church. He asked, because Black Catholic theologians speak of a distinctive culture and experience of Black Catholics, and since the diversity of gifts is destined to contribute to the whole, what are the distinctive gifts Black Catholics bring to the church? What is it that they contribute to the whole? The archbishop wished to open a conversation around gift-giving; he was confident in the unique gifts of Black Catholics offered to the whole.

Yet, the uninterrogated assumption was that Black Catholics must justify their full membership in the Church by way of their distinctive gifts whereas for white Catholics full membership is assumed and that whites constitute the foundational point of reference against which all other participants are viewed. Blackness remains a barrier. Blackness cannot be fully included except through a method of universalization, by translating its particularity into something that is transactable by white people.

Some Catholic attempts at inclusion, however well-intentioned, position whiteness as the core identity of the U.S. Catholic Church. Whiteness becomes a soteriology, a form of catholicity through which all others find ecclesial belonging. It is not simply that the Church fails to address the racism outside its doors, but that it fosters a discursive formation in whiteness that appears both in the corporate forms of relating that it cultivates (pastoral, educational, economic, familial) and in the expression of its identity (ecclesiology).

Evidence of ecclesiological whiteness appears even within the very attempts of the American church to address racism. A recent example stands out to me from the 2018 pastoral letter on racism by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Open Wide Our Hearts. Despite its renunciation of individual and systemic racism, the document opposes Catholicism and non-white identities throughout its pages. Only once does it explicitly identify a Black, Latino, or American Indian as being authentically Catholic.

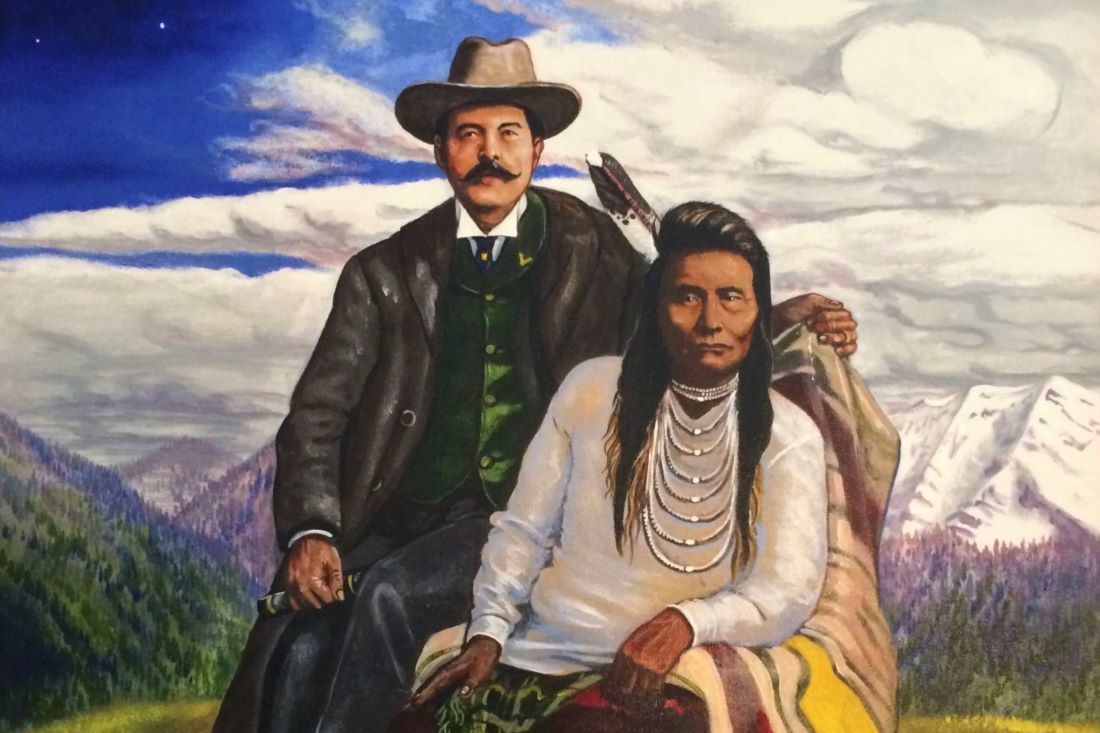

In a section discussing the historical relationship between the Catholic Church in the Americas and American Indians, it reads, “Many, but certainly not all, Native peoples accepted the Gospel willingly. For instance, St. Kateri Tekakwitha, Nicholas William Black Elk, Sr., and the martyrs of La Florida Missions were moved by Christ’s message of love, and by the example of Christians who honored their dignity.”[6] The document places indigenous people in a position of passive reception of the Gospel while never identifying them as Catholic. At the same time, Christians, who are supposedly white, set the example by which the indigenous people were moved. Whites are placed in the position of “honoring their dignity”: recognizing, judging, determining, and accepting them into the story of salvation.

American Indians are given only the role of attuning themselves to whiteness, orienting their lives around white bodies. The historical record, however, speaks not of the passivity of Kateri, Black Elk, or the La Florida martyrs, but of their heroic sanctity in the form of active evangelization and mysticism. Thus, Open Wide Our Hearts, by obscuring the Catholic identity of native people, preserves whiteness as the gatekeeper to Catholicism against the stated intentions of its authors. It shows that whiteness is durable and resilient.

The American Heresy

Racism is frequently described as “America’s original sin.”[7] If racism is its original sin, it would be fitting to describe whiteness as America’s original heresy. Ecclesiologically speaking, it is heresy, an (often-polemical) category describing communities that separate themselves from orthodox faith. In its expansive meaning, heresy is not only the rejection of doctrinal formulae, but a rejection of normative Christian practice that causes division within the body of Christ. In this sense, Augustine counted as heretics those who were enemies within the Church who introduced dissension and confusion among the faithful, scandalized potential converts, and gave the enemies of the Church ammunition against it.[8]

Whiteness is a pathological ecclesial identity insofar as it proposes a false unity. It neutralizes the capacity for connection, belonging, and love. It mutes the possibility of encounter. It is incontrovertible that the Catholic Church in the United States taught and practiced heresy for most of its existence through its collaboration in slavery, Jim Crow, segregation, and racial inequality. Those practices by which one enters into the Church and one’s life is continually inscribed in it were at the same time formations in white supremacy. This does not imply that masses and sacraments celebrated were somehow ineffectual as a means of grace. But it does suggest that the U.S. Catholic Church proposed a false catholicity, a counter-witness to the gospel that reverses the meaning of creation and redemption.

There is justification to use the language of heresy with regard to whiteness. In his book Black Theology and Black Power (1969) James Cone (1938–2018) framed his argument in the oppositional terms of orthodoxy and heresy. “Black power,” he said, is not a “heretical idea. It is, rather, Christ’s central message to twentieth-century America.”[9] Reminiscent of early Church polemicists, he charged the white church in the United States (particularly white Protestantism) with heresy for its conspiracy in dehumanizing oppression:

It was, rather, white Christianity in America that was born in heresy. Its very coming to be was an attempt to reconcile the impossible—slavery and Christianity. And the existence of the Black churches is a visible reminder of its apostasy. The Black church is the only church in America which remained recognizably Christian during pre-Civil War days.[10]

For Cone, heresy is not a moral failure (individual or social), but the disfiguration of the Church’s identity and failure of its calling. In this sense, he explained that the “white church has not merely failed to render services to the poor, but has failed miserably in being a visible manifestation to the world of God’s intention for humanity and in proclaiming the gospel to the world.”[11]

The white church’s complicity in slavery, Jim Crow, segregation, and ongoing inequality is not only a moral failure, but an apostasy of its identity, a failure to be the community in which God’s plan for humanity is unfolding. Cone specifies the church’s “basic heresy” as the pathological desire by whites to have God without blackness, a desire that infects both doctrine and practice.[12]

This heresy persisted from its beginnings in the white American church and, according to Cone, had to be continually confronted in the history of American Christianity. In his Preface to the 1989 edition, he states “civil rights activists did much to rescue the gospel from the heresy of white churches.”[13] With the passion and intellectual rigor reflective of the patristic period, Cone treats white Christianity as a heretical sect rather than as the Christian Church.

In his dialogues with Catholic theologians, Cone presented Black liberation theology as a challenge to a heretical tendency within the Church. His article, “Black Liberation Theology and Black Catholics: A Critical Conversation” (2000), renewing his persistent question whether “one can be racist and Christian at the same time,” addressed American Catholicism. He said,

If one concludes that it is impossible to be racist and Christian, he or she will be forced to interrogate the meaning of racism in order to oppose this terrible evil. If one concludes that racism is not an issue that involves Christian identity, one will not feel the need to make a theological examination of it.[14]

Cone suggested that Black Catholic theologians so far had been fighting for their place at the table, but had not yet risen to critically challenge the racism embedded in the theological tradition. I do not believe Cone fully appreciated the historical and methodological work that Black Catholic theologians like M. Shawn Copeland, Cyprian Davis, Jaime Phelps, and Diana L. Hayes had already accomplished at the time. Their theology was not simply an apologia for one’s place at the table. They drew from a Black Catholicism that had been there all along, discovering in Black Catholic communities the methods for theological transformation. And they also inhabited contemporary theological language, sources, and methods to direct them toward a critical challenge of racism in the tradition.

Nevertheless, Cone grasped the struggle of Black Catholics to preserve an identity that was both Black and Catholic, and his criticisms were aimed at preserving the fidelity and integrity of Christian life. He wrote,

The contradictions that Black Catholics seem to express in their writings are not primarily with the Catholic faith but with its practice in ethics, liturgy, and other pastoral aspects. But how can the ethics of the Church be flawed and not its theology? How can people think correctly about God and treat their neighbors as subhuman?[15]

For Cone, the lived practice of the Church and its noetic expressions of faith are inseparable. And just as white American Protestantism had succumbed to heresy, so did Catholicism. The mission of Black theologians was to restore the gospel.

Cone’s provocative language to describe white American Christianity is more than rhetorical. His understanding of heresy has much in common with recent scholarship on heresy in the early Church, which focuses more on heretical communities than they do on individual heretics. As Michael Stuart Williams explains, in late antiquity:

Christian communities were thus rather broad-based and loose-knit, constituted by shared symbols and rituals rather than by common allegiance to a narrowly defined doctrinal agenda. For the most part they were bound together by a “common Christianity” rather than by any strong sectarian identity.[16]

The borders of the Christian church in the first centuries were not fixed and statically tied to shared belief.

They were complex and fluid, operating in relationship to overlapping ethnic, linguistic, social, and economic identities based on shared practices. Often, opposing doctrinal parties were more like temporary coalitions than strictly delineated sects.[17] Heresy in late antiquity was less a matter of a cohesive doctrinal ideology with clearly articulated boundaries than it was a matter of a division in the community opened by the mobilization of distinct practices and articulations of belief in the formation of opposing ecclesial identities.

By these definitions racism has been church-dividing in the United States. White U.S. Methodism separated itself from the orthodox faith preserved in the African Methodist Episcopal church because of its racist ecclesial practices. White U.S. Catholicism also aligned its sacramental and institutional practices with white supremacy in opposition to orthodox faith. Benedict Joseph Flaget (1763–1850), the first bishop of Bardstown, Kentucky was one of the largest slaveholders in Kentucky.[18] He bought slaves for the diocese and gave them to his successor, Bishop Martin John Spalding (1810–1872), who was already a slave-owner when he became bishop.[19]

Flaget insisted that slaves were happier in the state of enslavement than freedom. Pope Gregory XVI, in 1839, condemned the practice of enslavement of Blacks and Indians in In Supremo apostolatus: “We consider it to belong to our pastoral solicitude to avert the faithful from the inhuman trade in Negroes and all other groups of humans.”[20]

But the pope’s teaching was largely rejected or ignored in the United States. In an 1840 letter to U.S. Secretary of State John Forsyth, Bishop John England of Charlestown argued that Pope Gregory XVI’s condemnation of slavery did not apply to the United States. Since slaves were no longer being brought stateside from Africa, slavery in America was not a “trade in Negroes.” In a circular argument, he reasoned, if the pope’s prohibition did apply, the bishops would be required to deny sacraments to slaveholders, who are “among the most pious and religious of their flocks.”[21] Since they do not withhold sacraments to slaveholders, he reasoned, the condemnation could not possibly apply to domestic slaveholding. The U.S. Catholic bishops frequently rejected both Catholic doctrine and moral practice in favor of an ungodly alliance with American slavocracy.

Moreover, throughout the history of the American Catholic Church, its alliances with dispossession of indigenous lands, segregation, racial discrimination, and white supremacy continued.[22] We can see this tacit alliance within a single city. When it came to segregation, the Louisville Archdiocese generally declared its neutrality. In 1960, the Louisville Archdiocese stated segregation was at odds with Christianity, but it also explained that forcing integration would be counterproductive. In 1976, an anti-desegregation rally began at a Catholic church in Louisville’s west end and continued with a parade of one hundred vehicles in the “Spirit of ‘76” protest.[23]

While there are certainly instances in the city’s history of individual Catholics struggling for racial justice, diocesan schools, parishes, and clergy generally oriented their responses to accommodate white parishioners. A telling incident occurred in 1954, after Charlotte Wade and Andrew Wade, a Black World War II veteran, bought a home in the Rone Court housing development in Shively, at the time a near-Louisville suburb.

The Wade family was harassed and threatened. A cross was ignited on the adjacent lot, rocks were thrown through their window, their house was shot at, and then bombed. When Wade and his advocates sought support from local clergy, the local Catholic priests denied that his house belonged within their parish.[24] This position was jurisdictional, a denial that this incident was something occurring within the parish boundaries. But, furthermore, it was a denial that the Church had any resistance to the violent policing of the borders of whiteness, a space organized by the exclusion of Blacks.

The problem that Cone identifies in his engagement with Black Catholic theologians is that racism is often narrowly-construed as an ethical failure of individuals rather than a radical departure from collective Christian identity. But the papal condemnations of slavery have historically interpreted that racial exploitation of human beings opposes God’s plan by shattering the union of humanity in the body of Christ, placing the souls of slavers at risk, and creating obstacles to the spread of the faith. As slavery was generally eliminated as an economic institution, papal teaching from Gregory XVI to Pius XI generally echoed the understanding that racial oppression was an obstacle to ecclesial unity and ideological rationalizations for it contravened Catholic doctrine.

Practices of racialized oppression relegate a group of people to a lower plane of humanity; but this relegation is a deformity of ecclesial existence. The “color line” is drawn across the unity of the Church. I believe that the authors of the 1968 Statement of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus understood this. Like the Barmen Declaration (1934), which condemned the German church’s complicity with Nazism, the Black Catholic Clergy Caucus condemned the American church’s complicity with racism, recognizing it as a corruption of ecclesial identity. Its opening sentence was a bombshell: “The Catholic Church in the United States, primarily a white racist institution, has addressed itself primarily to white society and is definitely a part of that society.”[25] The statement rebukes the Church for what it has become—an institution that aligns itself with whiteness—while prophetically calling it to be what it should be. Whiteness is a pathological ecclesiology that opposes the unity of the catholica.

After Ecclesiological Whiteness?

Open Wide Our Hearts stated, “Racism is a moral problem that requires a moral remedy—a transformation of the human heart—that impels us to act.”[26] While this is true, calling racism a “moral problem” risks becoming a deflection. It rightly points to the interior of the human heart; it fails to point to the interior of the Church. It correctly locates racism in the individual; it fails to locate it in the collective. And by restricting racism to morality, it does not identify the damage racism inflicts on the faith, doctrine, and identity of the Church.

Fifty years ago, James Cone called out the white churches for their heresy. If whiteness is a pathology infecting the ecclesial identity, we might conclude that the U.S. Catholic Church is a sect with profoundly heretical tendencies. Although it no longer explicitly teaches heretical doctrine, these heretical tendencies persist within the very transmission of Tradition. The very institutions and actions by which the faith is passed on are also sites of the pathological transmission of Tradition where whiteness is written into the religious aspirations of a community. Can the American Catholic Church imagine itself apart from the false catholicity that calls and convenes it?

Despite the resilience of ecclesiological whiteness, we can imagine a different form of belonging in the body of Christ. In 2001, the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus (NBCCC) issued a statement contextualizing racism historically by narrating the 500 years since the first slave was brought to Hispaniola, and the genocide of indigenous people in the Americas.[27] It was a hemispheric, rather than national, approach to the problem of whiteness, reflecting an understanding that colonization brought together Europeans, Africans, and indigenous Americans through relationships of exploitation.

Within an historical account of colonization, it narrated the Genesis story of Joseph, a story of a family wounded by jealousy and the sale of a brother into slavery and of Joseph’s mercy towards his family. Joseph’s family is a theological type of the Church that suggests two ecclesiological implications. First, like Joseph’s brothers, the Church in the modern American hemisphere is not whole. It is fragmented by violence and its lasting trauma. To be the agent of God’s will, it must submit itself to a difficult course of conversion and redemption. Second, Joseph—the one rejected by his family and sold into slavery—is the one who has the capacity to reunite the family and to make it whole.

Like Joseph, those who are often perceived as peripheral, external, or irrelevant to the Church are those who possess the capacity to convene it under an authentic catholicity. The image of Joseph, in the phrase of M. Shawn Copeland, “(Re)marks the flesh of the church,” fundamentally reorienting where the body of Christ is to be found.[28]

[1] Achille Mbembe, Critique of Black Reason (Durham, NC: Duke, 2017), 33, 11.

[2] Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination (New Haven: Yale, 2010), 8.

[3] See: Jeannine Hill Fletcher, The Sin of White Supremacy (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2017).

[4] Cyprian Davis, OSB, “Reclaiming the Spirit: On Teaching Church History: Why Can’t They Be More Like Us?,” in Black and Catholic—The Challenge and Gift of Black Folk (Milwaukee: Marquette, 1995), 46–47.

[5] Katie Walker Grimes, Christ Divided (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2017), xxiii.

[6] United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love: A Pastoral Letter Against Racism (Washington, DC: USCCB, 2018), 12.

[7] One example is Jim Wallis, America’s Original Sin (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2017).

[8] See Aurelius Augustine, City of God (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1960), 18:51.

[9] James H. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1997), 1.

[10] Ibid., 103.

[11] Ibid., 71.

[12] Ibid., 150.

[13] Ibid., vii.

[14] James H. Cone, “Black Liberation Theology and Black Catholics: A Critical Conversation,” Theological Studies 61 (2000): 737.

[15] Ibid., 739.

[16] Michael Stuart Williams, The Politics of Heresy in Ambrose of Milan (Cambridge: CUP, 2017), 37.

[17] Ibid., 31.

[18] C. Walker Gollar, “Jesuit Education and Slavery in Kentucky, 1832–1868,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 108, No. 3 (Summer 2010): 220.

[19] See: Grimes, op. cit., 112.

[20] In Pius Onyemechi Adiele, The Popes, the Catholic Church, and the Transatlantic Enslavement of Black Africans, 1418–1839 (Hildesheim, Germany: Georg Olms Verlag, 2017), 399.

[21] John England, Letters of the Late Bishop England to the Hon. John Forsyth on the Subject of Domestic Slavery (Baltimore: John Murphy, 1944), 20.

[22] See, Fletcher, The Sin of White Supremacy and Bryan N. Massingale, Racial Justice and the Catholic Church.

[23] These examples are taken from Tracy E. K’Meyer, Civil Rights in the Gateway to the South, 1945-1980 (Lexington: Kentucky, 2009), 93, 265.

[24] Ibid., 65.

[25] “A Statement of the Black Catholic Clergy Caucus,” 111 in “Stamped with the Image of God”: African Americans as God’s Image in Black, eds., Cyprian Davis, OSB, and Jamie Phelps, OP (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2003).

[26] Open Wide Our Hearts, 20.

[27] The National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus, “The National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus Statement on Racism: A Sankofa Observance of the 500th Anniversary of the First Enslaved African to Enter the Western Hemisphere (1501-2001)” (2001).

[28] See: M. Shawn Copeland, Enfleshing Freedom (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2010), 81.