Fine writers help us "see" things in tangible ways and "feel" things through intangible means. Their ability to turn the world at a tilt, to explore our humanity and inhumanity challenges.[1]

—Emile Townes

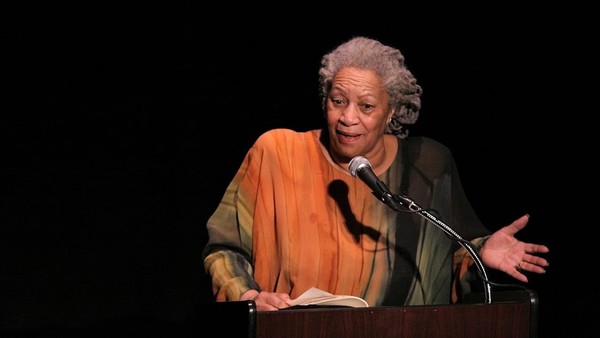

Unquestionably, the late Nobel laureate Toni Morrison is such a writer. In Song of Solomon, Morrison blends elements of African Traditional Religion (ATR), of African and African American history and folklore, and of Catholicism in order to turn our world at a startling tilt.[2] Critics write appreciatively of this intricate religio-cultural mélange in Song of Solomon, but typically link the characters, especially Macon Dead III (aka Milkman) and his aunt Pilate Dead to quest figures or to failed rites of passage or to Greek mythology. Few critics explore connections between Song of Solomon and Christianity; even fewer consider the novel’s relation to themes or elements of Catholic spirituality.[3]

Therefore, in what follows, we will consider how spirituality, memory, sacramentals, and communion—themes and symbols with special Catholic resonance—figure in the novel. Part 1 briefly sets out the structure of the novel, calls attention to literary devices, chronology, geography, and references to historical events and persons. Song of Solomon is a psychological novel, more concerned with an examination of the inner lives of its characters and their responses to historical and familiar circumstances, than with action. Part 2 sketches the relationships between some of the characters and their efforts to resolve friction between themselves and to wrestle with their inner tensions. Part 3 focuses on spirituality and emphasizes resonances to Catholic spirituality and theology.

Two caveats: First, although Toni Morrison was Catholic and a novelist, the aim here is not to determine whether Song of Solomon is a Catholic novel.[4] Scottish born novelist and Catholic convert Dame Muriel Spark once remarked, “there is no such thing as a Catholic novel unless it’s a piece of propaganda.”[5] Second, an apologia or account of guiding principles for the critical reading or interpretation that follows is in order. This should ward off suspicions about theologians distorting or instrumentalizing fiction. The philosopher of aesthetics Theodor Adorno reminds us that “art may be the only remaining medium of truth in an age of incomprehensible terror and suffering.”[6] Literature teaches and tutors us, coaxes and coaches us—all of us, even theologians—in the mysteries of the human mind and human heart. The essay intends neither to probe every passage in search of the supernatural, nor to shove the novel into doctrinal suppositions. Well-written, demanding novels challenge; they resist reduction to both naive literalism and over-blown symbolizing. Theology and literature draw our attention to what is vital and important, turn us toward what is transcendent, toward what transcends us, toward potentialities of our own self-transcendence. In an act of sublation, literature and theology gather us and move us to other (and deeper) densities of experience and thought, of understanding and judgment, of pleasure and beauty, of terror and awe.[7] The intensity of encounter with literature requires the theologian (indeed, any interpreter) to proceed with humble respect for the act of literary creation, to meet the work with courtesy and with sensitivity to the writer’s language;[8] to inhabit patience and sympathy in reading; and, in the words of literary critic Derek Attridge, “to read creatively in an attempt to respond fully and responsibly to the alterity and singularity of the text.”[9] Moreover, the theologian (read: interpreter) must, to quote Attridge again, “work against the mind’s tendency to assimilate the other to the same”[10] and, finally, move with great delicacy and daring in creative interpretation.

The Structure of Song of Solomon

Song of Solomon is a complex, open-ended, paradoxical novel crafted within an Afrocentric horizon in which story-telling or narrative “has never been merely entertainment.”[11] The novel opens in media res, that is, in the middle of things; gradually, the omniscient narrator fills us in through literary devices such as flashbacks, re-creation of dialogue, exposition of the various characters’ innermost thoughts and motivations, and reconstructions of past events. Chronologically or temporally, the novel covers nearly a century—three generations of a black family, enslaved then emancipated. The reader learns the family’s history through gradual disclosure of fragments of memory and legend, folksongs and children’s games, folk beliefs, rituals and historical events. All this “coalesces into a past.”[12] In Song of Solomon, Morrison creates a cosmology redolent of the worldview of the BaKongo peoples, whose ancient kingdom included parts of present-day Angola, Gabon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Congo Brazzaville or the Congo Republic. From this culture comes the powerful and empowering metaphor of flying that opens and closes the novel. For, this particular African people possessed the power of physical flight.[13]

In Song of Solomon, Morrison builds “detailed chronological [and historical] scaffolding” that not only tracks the destiny of the descendants of Solomon, the Flying African,[14] but situates their lives within documented historical events and persons—the First World War, Prohibition, the Depression, the death of Emmett Till, “Jim Crow,” movements for Civil Rights, Father Divine, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and John Fitzgerald Kennedy. The historical context of the narrative “stands as a reminder of the consequences of living as the characters do, with little awareness of the historical forces affecting their lives.”[15]

Summary Sketch of Some of the Main Characters

Song of Solomon begins in media res—quite precisely, on Wednesday, the 18th of February, 1931. Mr. Robert Smith, a black North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance[16] agent has promised to fly from the top of Mercy Hospital to the other side of Lake Superior at 3:00 p.m. By 11 o’clock in the morning 40 or 50 people, mostly black, have gathered to watch. The crowd mills about, uncertain, perhaps daydreaming, until a woman bursts into song.

This is our introduction to the novel’s central female character, Pilate Dead: She wears a knitted navy cap pulled far down over her forehead and is wrapped in an old quilt rather than a winter coat (6-7). “Her head cocked to one side, her eyes fixed on Mr. Smith, she sang in a powerful contralto:”

O Sugarman done fly away

Sugarman done gone

Sugarman cut across the sky

Sugarman gone home . . .

Also standing among the crowd is Ruth Foster Dead, well-dressed in a “neat gray coat … a black cloche, and a pair of four-button ladies’ galoshes.” Ruth is married to prosperous black property owner and landlord Macon Dead, Jr., Pilate’s brother. The shock of Mr. Smith’s attempt to fly away on his own wings causes Ruth to go into labor. The next day the novel’s central male character, Macon (known as “Milkman”) Dead III is born in what previously was the all-white Mercy Hospital (3-9). If Pilate sings to comfort the crowd, perhaps, even to explain the insurance agent’s actions, the song is the thread that the adult Milkman will follow, scaling rough physical, relational, and spiritual terrain, to find himself, to find wholeness.

Rather quickly, the narrator moves us backward, relating the origin of the peculiar surname, Dead. Following the end of the Civil War and Emancipation, Jake arrives to register at the Virginia office of The Freedmen’s Bureau.[17] When questioned, Jake replies that he is from Macon, Virginia, and that his family is dead. The Union soldier charged with recording the information is unfocused, half-listening, and drunk; he “scrawl[s] in perfect thoughtlessness” Jake's name as “Macon Dead.” Jake is the first Macon Dead; he passes this name on to his first born son Macon Dead, Jr., who, in turn, passes the name on to his first born son, Macon Dead III.

The first Macon names his daughter by opening the Bible at random and putting his finger on a word. When he performs this ritual, the first Macon is soaked in angry grief; his wife Ryna has died giving birth to the infant girl. Unable to read, Macon carefully copies the letters on a slip of paper that he hands to the midwife, Circe, who promptly shouts that he cannot name his daughter “Pilate.”

“Like a riverboat pilot?” Macon asks.

“No not like no riverboat pilot. Like a Christ-killer Pilate. You can’t get much worse than that for a name. And a baby girl at that.”

“That’s where my finger went down at.”

“Well your brain ain’t got to follow it. You don’t want to give this motherless child the name of the man that killed Jesus, do you?”

“I asked Jesus to save me my wife.”

“Careful, Macon.”

“I asked him all night long.”

“He give you your baby.”

“Yes. He did. Baby name Pilate.”

“Jesus, have mercy.”

“Where you going with that piece of paper?”

“It’s going back where it came from. Right in the Devil’s flames.”

“Give it here. It comes from the Bible. It stays in the Bible.”

And it did stay there, until the baby girl turned twelve years old and took it out, folded it up into a tiny knot and put in a little brass box, and strung the entire contraption through her left earlobe (19).

The first Macon was clever, industrious, and successful; after 16 years of backbreaking labor, he had one of the best farms in Montour County, Pennsylvania (235). But the wealthy white gentlemen farmers of the Butler family resented, even envied, this black man’s progress. They killed him for his property. Fearful, 16 year-old Macon Jr., and 12 year-old Pilate bury their father in a shallow rock-covered grave, then take refuge with the midwife Circe. For two weeks, Circe hides the siblings; but they are nervous and edgy, and so head out for Virginia, where Macon Jr., thinks they might have family. Along the way, they seek shelter in a cave. After a fitful night’s sleep, Macon Jr., walks deep into the cave’s interior to relieve himself; there he accidentally awakens an old white man. When the man groggily stumbles toward him, Macon, fearing for his sister and his life kills him. In trying to hide his body, the siblings discover sacks of gold nuggets in a shallow pit deep in the cave. Macon wants to take the gold; Pilate, thinking it wrong, does not. They argue, come to blows, then part company. Three days after their fight Macon Jr., returned to the cave to recover the gold, but the sacks are gone; he assumes that Pilate has taken them. Macon Jr. leaves and will not see his sister again for nearly 50 years. When the siblings finally meet, Pilate acknowledges that she did return to the cave, but seven or eight years later and only at the bidding of the spirit of their deceased father to collect the bones of the murdered man.

After the fight with her brother, Pilate becomes a wanderer. For nearly four years, she zigzags her way from Pennsylvania to Virginia to West Virginia, to upstate New York, and back to Virginia. Along the way, she joins migrant workers picking crops or finds work in laundries. All the while, she carries a geography book and souvenir rocks—one collected from each place to which she traveled. When she reaches Culpepper, Virginia, Pilate takes work washing laundry in a hotel. In town, she hears talk of 25 or 30 black families who live on an island off the coast. She pays the then-extravagant sum of a nickel for passage across from the mainland. After three months of hard, but re-creative outdoor labor, Pilate takes a common-law husband and roughly a year later gives birth to a daughter, Reba. The narrator explains that in the thick fog of depression and loneliness following Reba’s birth, the spirit of her father Macon came to Pilate and admonished, “Sing. sing,” and “You just can’t fly on off and leave a body” (147). Pilate took this to mean that she should sing and she did; and that she should return to the Pennsylvania cave to collect what was left of the man murdered so many years ago.

When Reba was two years old, Pilate surrendered again to restlessness and struck out to wander (about 1913). The two of them moved around until, Reba was 16 or 18 years old; then Pilate settled them in the colored section of a small unnamed town and began to work as a bootlegger. Not too long after, Reba gives birth to a daughter whom she names Hagar. When Hagar is of school age, Pilate determines that her granddaughter “needed family, people, a life very different from what she and Reba could offer” (151). She searches for and finds her brother Macon Jr. In 1930, a year or so prior to Milkman’s birth, Pilate, her daughter Reba and granddaughter Hagar take the train to an unnamed town in Michigan where her brother and his family live.

Pilate found her brother Macon Jr. conventional and embarrassed by her manner of dress and decorum. He had become a prosperous and pitiless landlord, belligerent and vindictive. Macon Jr. is contemptuous of his wife Ruth, disdainful of his daughters Magdalene (Lena) and First Corinthians, suspicious and hostile toward his son Milkman. If the brother has grown mean, selfish, and grasping, fixed on getting money and property, the sister is opposite. Pilate is a natural healer, a root-worker; her experiences of rejection have “ripened” into deep compassion for troubled people, generous hospitality, gentleness with animals, familiarity with and love of the earth, and “deep concern for and about human relationships” (149). Macon Jr. receives Pilate grudgingly, but remembers the gold and, surprisingly, assumes that his sister still has it.

As a boy, Macon Jr.’s son Milkman was mesmerized by his aunt Pilate, alternately shy and sullen, genial and eager for her attention. As a young adult, he is sexually attracted to Hagar, his emotionally fragile second cousin, and begins an intense, but careless sexual relationship with her. Self-absorbed and spoiled, after several years, the 32 year old Milkman tires of Hagar, discards her, and abandons her to an emotional breakdown. To avoid her ongoing attention, Milkman decides to leave town for a year or two, and asks his father to finance the escape. Macon Jr. tells him about the gold from the cave and convinces his son that it is hidden in Pilate’s house, stealing it would support Milkman’s getaway and augment his own finances.

Milkman imagines that the gold is hidden in plain sight in the old moss-green sack suspended from the ceiling in Pilate’s house; after all Hagar once told him that Pilate calls the bag “her inheritance” (39). Milkman and his best friend Guitar Baines steal the bag, but it contains only rocks and human bones. Angry at coming up empty, they decide that the gold must still be in the cave. Milkman resolves to recover the gold and promises a share to Guitar, who plans to use the money to fund a secret society that avenges injustices perpetrated against African Americans. But Milkman wants to make the journey alone—without his friend.

Milkman traveled by plane, train, bus, and automobile first, to Virginia, then to Pennsylvania. Much like a detective, he asked questions of all the people he met, searching for clues to the puzzle of his family. For days, Milkman marveled as old men relived their youth, recalling their admiration for his grandfather; listened intently as Reverend Cooper, Circe, and Susan Byrd recount memories of his great-grandfather, grandfather, father, and aunt. The fragments of their memories stretch Milkman; he wrestles with their implications, but the whole eludes him.

On his last day in Shalimar, Virginia, at six-thirty in the morning, Milkman waits for the repairs to his car to be completed. Restless, he walks around the bustling little town and catches the sound of children playing (299-300). Almost in spite of himself, he is drawn to their singing; he leans against a large cedar tree to listen and to watch. The children begin a familiar song, one he had heard off and on all his life, the old “blues song” Pilate sang: “O Sugarman don’t leave me here,” except the children sing, “Solomon don’t leave me here” (300-301). Milkman listens more intently and recognizes that the children are singing about his ancestors, his family:

Jake the only son of Solomon

Come booba yalle, come booba tambee

Whirled about and touched the sun

Come konka yalle, come konka tambeeLeft that baby in a white man’s house

Come booba yalle, come booba tambee

Heddy took him to a red man’s house

Come konka yalle, come konka tambeeBlack lady fell down on the ground

Come booba yalle, come booba tambee

Threw her body all around

Come konka yalle, come konka tambeeSolomon and Ryna Belali Shalut

Yaruba Medina Muhammet too.

Nestor Kalina Saraka cake

Twenty-one children, the last one Jake!O Solomon don’t leave me here

Cotton balls to choke me

O Solomon don’t leave me here

Bukra’s arms to yoke meSolomon done fly, Solomon done gone

Solomon cut across the sky, Solomon gone home.[18]

Clutching the words to the round, Milkman returns to Susan Byrd who helps him to sort and rearrange the pieces of his genealogical puzzle. One day his enslaved paternal great-grandparents, Solomon (Shalimar) and Ryna were working in a cotton field. Suddenly, Solomon threw down the hoe, ran up a hill, spun around, and flew off into the air back to Africa. Although he gains freedom, Solomon’s flight from slavery wounds the family. He left behind his wife Ryna, who in anguish goes insane, and their 21 male children. Solomon tried to take the infant Jake with him, but the infant slipped from his grasp. Heddy, perhaps an Algonquin woman, who has come up to the big house to help with soap-making and candle-making, finds and raises Jake, who, as a young man, marries her daughter Sing.

Once Milkman grasps that the children’s song is about Solomon, the song of Solomon, he is fundamentally and profoundly changed. What began as a material quest evolved into a spiritual journey; Milkman has found a treasure far more precious than gold. He has found “his family’s history in fact and [in] feeling.”[19] The people of Shalimar, Virginia, have given him a powerful and empowering spiritual gift—the key to his past, his identity, his wholeness.

After surviving an assassination attempt by Guitar, who has been trailing him, Milkman returns home to Michigan with the startling story of his paternal great-grandparents and grandparents. He and Pilate return to Shalimar to bury Jake’s bones on Solomon’s Leap, the mountain from which Solomon flew back to Africa. After burying the bones, Pilate is struck dead by a bullet that Guitar had intended for Milkman. Shattered and heartbroken at Pilate’s death, Milkman calls out Guitar’s name and leaps toward him.

Spirituality in Song of Solomon, A Catholic Reading

Some readers may find the notion of spirituality in relation to Song of Solomon surprising. Others may think that linking the novel to Catholicism or Catholic spirituality to be dubious or odd or even, flat-out wrong. On the one hand, Catholicism in the United States presents itself, almost exclusively, as the faith of European immigrants, thus, separate from or exterior to African American experience. On the other hand, literary critic Erin Salius suggests that “when we look closely, Catholicism appears at the margins of a significant number of significant works throughout the canon of African American literature.”[20] In the third part, the essay interrogates some striking features of Catholicism in Song of Solomon. The purpose is to open space for appreciation of the protean spiritual potential of aesthetic creation.

Spirituality in Song of Solomon: What is meant by spirituality? The most basic and heuristic definition of spirituality is that it is a way of life, a way of living, a way of being in and moving with and through the world. This shorthand definition coincides with that advanced by biblical exegete Sandra Schneiders. Spirituality, according to Schneiders is “a relatively developed relationality to self, others, world, and the Transcendent, whether . . . called God or designated by some other term.”[21] Catholicism is, of course, a religion, yet, to put it radically, Catholicism is a spirituality. In other words, first and foremost, Catholicism is a way of life, a way of living, a way of being in and moving with and through the world. Thus, as a way of life, a way of living, Catholic spirituality enfleshes and sacralizes memory and word, mystery (sacrament) and materiality (sacramentals), community and communion. Moreover, this way of life and living extends the presence of the Word made Flesh through community and communion in and through and beyond time.

Some of the chief features of a Catholic spirituality include: focus on Jesus of Nazareth and his Mother; the incorporation of material objects in devotional life; concrete expression of the “the principle of both/and”—e.g., both grace and freedom, both faith and reason, both order and charismatica, both tradition and innovation; and the prioritizing of memory, community, and communion.[22] To quote Schneiders again, spirituality “denotes experience . . . personal lived reality which has both active and passive dimensions;” it is an “experience of conscious involvement in a project of life-integration, pursued toward self-transcendence toward ultimate value.”[23]

The way in which Pilate Dead lives her life, the way she is, the way in which she moves in and with and through the world discloses a developed and developing relationality to self, others, world, and the transcendent. Developed and developing, because human living always is fragile praxis, enfleshing vulnerabilities and virtues, judgments and decisions, surrender and discipline, atonement and conversion. To be sure, the very name Pilate is problematic; but, perhaps, the first Macon Dead presciently grasps the irony of his girl-child’s name: Pilate Dead will be turn out to be a strong and certain healer, not a weak and equivocating executioner. Pilate Dead is a riverboat pilot: She perceptively and subtly, rather than ham-fistedly or didactically guides her family as they traverse the shoals of the river of life, navigate reckonings with moral and psychic challenges. Like a riverboat pilot, Pilate’s experience of moving with and through nature has resulted in much practical and useful knowledge; her talent as a natural healer has been augmented by training as a skilled rootworker or herbalist;[24] and she has gained valuable moral and social insight through her varied interactions with others.

Because early in her life Pilate was blunt and would not suffer fools; because she displayed little, if any, patience for condescending behavior and malicious gossip, she was driven repeatedly from the warmth of human companionship and community. This may account, in part, for her wandering. But, at some point, she makes a decision regarding her own life-integration. She throws away “every assumption she had learned and began at zero,” then tackled the problem of trying to decide how she wanted to live and what was valuable to her. When am I happy and when am I sad and what is the difference? What do I need to know to stay alive? What is true in the world? Throughout this fresh, if common pursuit of knowledge, one conviction crowned her efforts: since death held no terrors for her (she spoke often to the dead), she knew there was nothing to fear (159).

Always, Pilate is respectful and polite to everyone she meets and offers the hospitality of food and conversation to visitors; always, she is gentle with animals. Making wine and cooking whiskey not only stabilized her, but allowed her to root herself in a place and afforded her the freedom to sacralize or sanctify her time—hour by hour, day by day. Pilate seemed to lack a fixed schedule, rather she lived according to nature’s horarium (or daily schedule). She sanctified her time, engaging tasks that left her calm, still, and open to the currents of life. Pilate lived life on her own terms, measuring her choices by the extent to which they support her in realizing her humanity, in orienting herself toward self-transcendence.

Pilate collects rocks and bones, and she holds these objects as precious, as sacred; they are sacramentals. Sacramentals are physical objects, gestures, prayers that remind us of and orient us toward transcendence, toward the Transcendent.[25] The tiny brass box dangling from Pilate’s ear was her deceased mother’s snuff box; it contains the slip of paper on which her father has laboriously written her name. Wearing the earring venerates and memorializes her parents—the mother whom she never knew and the father who gave her the ambiguous gift of her name. The moss-green sack suspended from the ceiling in Pilate’s house functions as a reliquary for the bones she has retrieved and the rocks she has collected. Perhaps, we might appreciate this retrieval, preservation, and protection of the bones as an act of atonement. Pilate did not kill the man in the cave, but she took responsibility for the murder: She and her brother Macon Jr. were a unit, the orphaned brother and sister were one. At the conclusion of the novel, we learn that the sack, in fact, holds the bones of their father, Jake, the first Macon Dead. His shallow rock-covered grave flooded, his body floated up, and someone placed his remains in the cave. The spirit of the first Macon Dead appeared to his daughter so that she might bury him properly.

If Pilate is a riverboat pilot, she is also a harbor: She is grace and gift. She provides refuge to those who need home. When her nephew Milkman and his friend Guitar visit her house for the first time, they enter into sacred space conjured through memory and sacramentals. Milkman is swept up into a near trance by the incantatory sound of Pilate’s voice as she tells stories about his father and grandfather, by the way she pronounces words, by the smells of winemaking, and by the effect of strong sunlight streaming through uncovered windows. The narrator tells us that this visit was the first time in his life that Milkman “remembered being completely happy” (47). In this setting, Milkman receives and Pilate offers communion: Nourishing her nephew and his friend spiritually with fragments of family stories; and nourishing them existentially with joyous and companionable acceptance, with communion and community. Pilate’s memories and her singing not only evoke and transmit to Milkman knowledge of the past, but re-create the present, thereby, generating conditions for the possibility of a future for him that might be different from her own and that of her brother. Pilate’s lack of fear and her capacity for hope in facing death opens Milkman to risk: “Now he knew why he loved her so. Without ever leaving the ground, she could fly” (336).

Conclusion

Catholic spirituality? Spirituality encompassing Catholic resonances? While the novel invokes neither Jesus Christ nor his Mother, it does display affinity for material Catholic devotional life. In addition, it illustrates the strength of character required to hold together opposing forces–hope and fear, gladness and sorrow, freedom and constraint; and prioritizes memory, community, and communion. The novel shows what “experience of conscious involvement in a project of life-integration, pursued toward self-transcendence toward ultimate value.”[26]

Like the African griots of old, Toni Morrison is an “oral weaver”[27] and like the best folktale or dilemma story, Song of Solomon is “indirectly didactic.”[28] The characters of the novel illustrate what it means to value family, venerate ancestors, cherish children and old people, honor friendship, and treat with courtesy and respect all those encountered along the way—what it means to be an authentic human being. Song of Solomon also illustrates just how dangerous it is to be found at crossroads, dangerous and decisive moments in life, without the healing and protective knowledge (sacred medicine) of one’s history, story, people, and family; the healing and protective knowledge of one’s purpose and direction.

A great novel, writes literary critic Ron David, “is not a list of facts that someone can explain to you. A great novel is an experience, aesthetic or spiritual (or both), that can only be known directly, one-on-one.”[29] This essay is meant to encourage the reader to engage Song of Solomon, and other Toni Morrison novels as well—and to do so for your own aesthetic and spiritual development and for the aesthetic and spiritual development of our nation’s realization of the common human good.

[1] Emilie M. Townes, Womanist Ethics and the Cultural Production of Evil (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 5.

[2] Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon (1977; New York: Plume Books, Penguin Books USA, 1987). Quotations will be taken from this edition and page numbers cited in the text.

[3] See Manuela López Ramírez, “Icarus and Daedalus in Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon,” Journal of English Studies, 10 (2012): 105-129. See Emily Paige Anderson, “Pilate Dead: Christian Love and Self-Sacrifice in Morrison’s Song of Solomon,” The Explicator 76, 1 (2018): 14-16 at 14; Nadra Nittle, “The Ghosts of Toni Morrison: A Catholic Writer Confronts the Legacy of Slavery,” America Magazine (November 3, 2017); and Erin Michael Salius, Sacraments of Memory: Catholicism and Slavery in Contemporary African American Literature (Gainesville: Florida, 2018).

[4] The second of four children, Toni Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford in Lorain, Ohio, a small then-industrial town twenty-five miles west of Cleveland. Inspired by a cousin from the ‘Catholic wing’ of her extended family, Morrison at the age of twelve became a Catholic, taking as her baptismal name Anthony, after St. Anthony of Padua. Reportedly, family and friends shortened it to Toni. In a 2015 interview with NPR’s ‘Fresh Air’ host Terry Gross, Morrison said that she no longer followed a “structured” religion but that she could be “easily seduced to go back to church.” She said: “I like the controversy as well as the beauty of this particular Pope Francis. He is very interesting to me” https://relevantmagazine.com/culture/books/toni-morrison-was-baptized-a-catholic-and-was-moved-by-the-beauty-of-pope-francis/

[5] Robert Hosmer, “An Interview with Dame Muriel Spark,” Salmagundi 146/147 (Spring 2005): 127-158, at 155.

[6] Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (London: Routledge, 1984), 27, cited in Susie Paulik Babka, Through the Dark Field: The Incarnation through an Aesthetics of Vulnerability (Collegeville: Liturgical, 2016), 3.

[7] I use sublation here as does Bernard Lonergan, Method in Theology 2nd ed., rev. aug., Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan, Volume14 (Toronto: Toronto, 2017), 227.

[8] See George Steiner, Real Presences (Chicago: Chicago, 1989), esp. Part III..

[9] Derek Attridge, The Singularity of Literature (London & New York: Routledge, 2004), Kindle ed. Loc 1637 of 4038.

[10] Ibid., Loc 1637 of 4038.

[11] Morrison, The Nobel Lecture in Literature, 1993 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 7.

[12] Morrison, “Memory, Creation, and Writing,” Thought 59, 235 (December 1984): 386.

[13] See: John M. Jantzen and Wyatt MacGaffey, An Anthology of Kongo Religion: Primary Texts from Lower Zaire (Lawrence: Kansas, 1974); Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Vintage, 1984).

[14] Melissa Walker, Down from the Mountaintop: Black Women’s Novels in the Wake of the Civil Rights Movement, 1966-1989 (New Haven: Yale, 1991), 134.

[15] Ibid., 132.

[16] The North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance was founded in 1898 to serve the insurance needs of African Americans who were overlooked or turned away from other insurance companies.

[17] Formally known as The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, the Freedmen’s Bureau was an agency of the U. S. Department of War, established in 1865 and initiated by President Abraham Lincoln. Tracey Baptiste writes: “The Bureau helped solve everyday problems of the newly freed slaves, such as obtaining clothing, food, water, health care, communication with family members, and jobs. Between 1865 and 1869, it distributed 15 million rations of food to freed African Americans as well as 5 million rations to impoverished whites. Its most significant achievements were in the fields of education—establishing day, night, industrial, and Sunday schools and assisted new established institutions of higher education such as Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), Howard, Fisk, and Atlanta (now Clark Atlanta) universities,” The Civil War and Reconstruction Eras (New York: The Britannica Educational, 2016), 48-49.

[18] Morrison insisted that “[Song of Solomon] is about black people who could fly. That was always part of the folklore of my life; flying was one of our gifts. I don’t care how silly it may seem. It was everywhere—people used to talk about it, it’s in the spirituals and gospels,” to Mel Watkins, Review of Tar Baby, The New York Times Book Review, September 11, 1977, cited in Ron David, Toni Morrison Explained: A Reader’s Road Map to the Novels (New York: Random House, 2000), 84.

Narratives about “flying Africans” are found in the Slave Narratives, see Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies among the Georgia Coastal Negroes (Athens: Georgia, 1940), 79, 81, 145. Variants of the story are found in folklore, see Langston Hughes and Arna Bontemps, eds., The Book of Negro Folklore (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1958), 62-65, Julius Lester, Black Folktales (New York: Grove, Inc., 1969), 147-152, and Virginia Hamilton, The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales as told by Virginia Hamilton (London: Walker, 1986), 166-173, and Monica Schuler, Alas, Alas, Congo: A Social History of Indentured Africans in Jamaica (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1980).

[19] David, Toni Morrison Explained, 80.

[20] Salius, Sacraments of Memory, 2. Morrison told Terry Gross on NPR that she no longer followed a “structured” religion but that she could be “easily seduced to go back to church.” She said: “I like the controversy as well as the beauty of this particular Pope Francis. He is very interesting to me.”

[21] Schneiders, “Religion vs. Spirituality: A Contemporary Conundrum,” in Spiritus A Journal of Christian Spirituality 3(2): 165.

[22] Gerald O’Collins and Martin Farrugia point out that some of these characteristics apply to other Christian traditions and some even apply to other religious traditions: “What is distinctive about [Catholicism as a religion and a spirituality] is not always and necessarily unique to Catholicism,” Catholicism: The Story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: OUP., 2003), 368.

[23] Schneiders, “Religion vs. Spirituality: A Contemporary Conundrum,” 167.

[24] Theophus Smith writes that “Rootwork … probably has to do with the preparation of potions from roots. In a broader sense rootwork can be defined as a highly organized system of beliefs shared by blacks who were raised in the Southeastern U. S. or who retain close ties there with family and friends . . . [and] consult a rootworker known also as a conjurer. The rootworker is believed to possess power to cast spells as well as remove them,” Conjuring Culture: Biblical Formations of Black America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 51 n. 52; see also Zora Neale Hurston, The Sanctified Church (Berkeley: Turtle Island Publishers, 1983), 15-40.

[25] These may include physical objects (e.g., candles, rosaries, medals, relics, statues, reliquaries), music (e.g., instrumental and sung), gestures (e.g., making the sign of the cross, processions, dancing), prayers (e.g., novenas, litanies).

[26] Schneiders, op. cit., at 167.

[27] Roger D. Abrahams, African Folktales (New York: Pantheon, 1983), 4.

[28] Gayle Jones, Liberating Voices: Oral Tradition in African American Literature (New York: Penguin, 1991), 177.

[29] David, Toni Morrison Explained.