This is what God does and this is who God is: the phil-anthropos, the lover of the human being.

—John Behr

If we don’t see that the choice is inevitable between the two supreme models, God and the devil, then we have already chosen the devil and his mimetic violence.

—René Girard

Since its first appearance in the late twentieth century, the concept of the postsecular has maintained a strong current in contemporary philosophy and literary studies. What scholars mean by the term can vary quite widely.[1] But within American literary studies, scholars tend to share a certain tone: they are circumspect and often openly suspicious when it comes to professed religious belief. Many of these studies feel as if they have come from scholars trained in the age of theory, an age that taught them, among other things, to subordinate personal faith commitments while privileging the cultural work texts do over any transcendent truths they might represent. Tracy Fessenden, for example, simplifies American Protestantism in order to describe the tradition as an effort at cultural domination.[2] John McClure, albeit with the best intentions, sets up a rigid dichotomy between faith and religion, in which faith is good and religion is bad.[3] In this dichotomy, faith is free and expansive, and religion is necessarily authoritative and enclosing. To be postsecular, argues McClure, is to offer something that looks and feels like religion but without any proscriptions. It is characterized by a kind of thinking “that repeats the possibility of religion without religion.”[4] In short, American writers employ a rather milquetoast “strategy of perhaps” and thereby rescue spirituality from the inherent violence of dogma.[5]

As the rest of McClure’s study proves, for writers like Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon, and Tony Kushner, this strategy makes sense. But has the systemic suspicion of organized religion and actual belief caused any critical blindness? Has it led to limited readings, or even to misreadings, of some of our contemporary novels? To answer that question I turn to a favorite novelist of postsecular theory, Toni Morrison. McClure walks an interesting line with Morrison since it is clear (even to McClure) that she does not see theistic faith and formal religion as mutually exclusive. Morrison “rejects fundamentalism, but she also refuses to reduce the traditional church to a vessel of oppression or to insist that the alternative spiritualities of people like Baby Suggs and Consolata are without their own risks and excesses.”[6] But rather than revise his dichotomy, McClure concludes that in Morrison’s text, faith in God is necessarily “partial” and does not rely on truth claims. Similarly, Amy Hungerford argues that Morrison flatly rejects the traditional authority of the Bible or organized religion in favor of its structure of internal allusiveness. She thereby “gathers all literary authority into herself” like Hungerford sees in Cormac McCarthy’s work.[7]

I contend that with Morrison’s work, especially a text like Beloved, this view is crippling. In its desire to reject religious misbehavior, it drains the power from a novel so defiantly insistent on spiritual realities. Beloved is unhesitant and unapologetic. It is more premodern than it is postmodern or postsecular. It illustrates that the literary artist’s power is at its height not by borrowing authority from scripture but when she embraces one of the oldest and most universal of all plots contained therein: light has come into the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. Beloved is a grotesque novel, and the power of the grotesque depends on the world viewed theologically.

The Grotesque

“124 was spiteful. Full of baby’s venom.”[8] With these opening words of her most celebrated novel, Toni Morrison ensured that she would be remembered as one of the masters of the grotesque. The grotesque reveals by way of contradiction, and it is difficult to think of something more shocking and incongruous to us than a spiteful ghost of a murdered baby haunting its mother with such intensity. And this ghost eventually becomes even more shocking: it takes on flesh, grows up, and moves into the house. All of this is proof that Morrison knows her audience well. We like our hauntings to remain abstract, and therefore hardly know what to think when this spirit insists on being something more than a psychopathological fantasy, sitting down as it does with the other characters to eat breakfast.

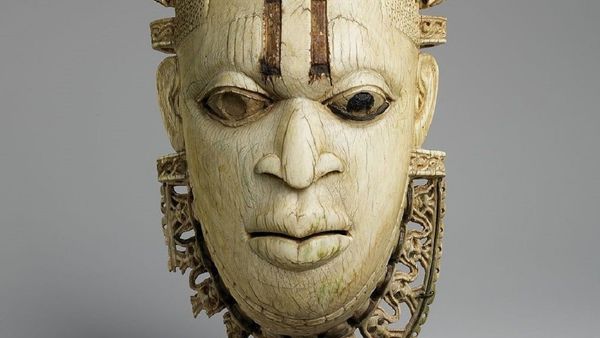

But as shocking as this ghost is for contemporary readers, Morrison’s literal use of the grotesque is quite conventional. The oldest appearances of the grotesque were the demons and gargoyles of painters and sculptors who actually believed in them—and in the corresponding angelic realm. These artists were trying to make the spiritual world visible to those who could not—or would not—see it. It is clear from Morrison’s interviews that she grew up with a family who, like these artists, did not find appearances from the beyond merely a psychological projection of troubled souls. In short, they were believers. And instead of chastising them as one might expect from an enlightened scholar, she insisted that her family’s experience of spiritual realities informed her sensibility as a writer.

They had visitations and they did not find that fact shocking and they had some sweet, intimate connection with things that were not empirically verifiable. It not only made them for me the most interesting people in the world—it was an enormous resource for the solution of certain kinds of problems. Without that, I think I would have been quite bereft because I would have been dependent on so-called scientific data to explain hopelessly unscientific things and also I would have relied on information that even subsequent objectivity has proved to be fraudulent, you see.[9]

Morrison’s antimaterialism is not merely a novelistic device; for her, much of human experience is “hopelessly unscientific.”[10] To rely on beings that appear from another realm is to insist, at the very least, that there are spiritual forces—forces for good and forces for evil. My argument thus begins with the observation that Beloved—whatever else she may stand for aside—is a demonic powerhouse.[11] This ghost is out to destroy Sethe and her family by crushing her spirit. And as soon as Morrison chooses to give real power and agency to the world of the beyond, she is also choosing to employ the grotesque in a conventionally theological way. The novel is thus powerfully premodern and rejects secular attempts to disenchant human experience.

Religious artists have often chosen to use gargoyles and devils to explain spiritual problems—particularly to warn us about encroaching evil, whether spiritual, physical, or moral. In his essay on the theological uses of the grotesque, Roger Hazelton argues that the “demonic is a matter of existential, and so of aesthetic, concern only for those who have faith in the divine.”[12] And, he adds, it is a matter of aesthetic concern only for those who ultimately believe that the divine is good, more powerful, and ultimately in control of the demonic. With a phrase that is precise but a bit of a mouthful, Paul Tillich named such an appearance the “divine anti-divine ambiguity of the demonic.”[13] In other words, God lets confusion reign by allowing the demonic have its way for a time, only to completely thwart it in the end.

The devil isn’t given his day only because it makes for a more interesting narrative. Instead, the purpose of the demonic grotesque is to demonstrate that the total revelation of evil—its full disclosure—is the necessary precursor to our struggle and victory against it.[14] The demon in Beloved makes a powerful appearance. Mimicking God, it demands total devotion, but behaving as a demon, it feeds like a parasite on being. But for all its power, it is clearly in the service of good, for, paradoxically, the more powerful the demonic becomes, the more it enables Sethe’s ultimate healing. Indeed, Sethe is freed from a living death and psychological slavery precisely at the moment in which the demonic makes its ultimate demands. And in this story about love, it is when the demonic most insists that love be reduced to the strangling reality of possessive desire that it is forced to yield to the greater power of love as charity.

To insist that Morrison’s use of the grotesque is theological is not at all to limit its rich symbolic significance, which has been aptly demonstrated.[15] Morrison resisted narrow readings of her novels, especially those that failed to take her fiction on its own terms and start with that. She tried to teach her students to “trust the tale and start with what you have.”[16] If we take that advice and also take a step back from the fiction as a whole, we find that the tale that Morrison tells over and over again is, at one level, remarkably simple. Her stories are about love and its absence, and they operate with the oldest narrative motivations: catharsis and revelation in characters and readers.

I am not making a claim here that Morrison’s ideas are explicitly or solely Christian; Morrison, following generations of African Americans, clearly draws religious ideas both from Africa and from the West. But far from the watered down versions of Christianity mentioned by McClure, she insists and demonstrates that African Americans found in authentic Christianity something that they needed to survive: a distinct focus on love. Not the western definition of erotic love, which Morrison saw as narcissistic and destructive, but love as charity extended through community to the “least of these.” Morrison said that it was these “love things” that were “psychically very important” to a people who have had to live a life of struggle against rage.[17] Africans coming to America incorporated Christianity into their spiritual lives because it included “the openness of being saved” and insisted on a transcendent love available to the “lamb, the victim, the vulnerable one who does die but nevertheless lives” (117). In other words, what appealed to them—in spite of the slaveholders’ abuse of Christianity—was the core of the gospel, the oldest promise of redemption and acceptance. “You were constantly being redeemed and reborn, and you couldn’t fall too far, and couldn’t ever fall completely and be totally thrown out . . . Everybody was ready to accept you” (117).

It is with this same “openness of being saved” that Toni Morrison begins Beloved. As Margaret Atwood argues, the epigraph from Romans 9—“I will call them my people, which were not my people; and her beloved, which was not beloved”—speaks to inclusiveness.[18] It is the promise of acceptance for a people previously scorned and rejected. It is, in short, a promise that good will win out over evil, no matter how powerful the evil. Morrison insisted that she wanted to dust off old myths like she dusts off words, and here she uncovers and represents the oldest of Christian myths: the devil will have his day, but love will prevail in the end.

The Grip of the Demonic: Despair

When the novel opens we find the demonic in control because Sethe is immobilized in despair. Isolated and scapegoated by the rest of the community, Sethe is perishing in stasis. By not actively choosing life, or trying to create a different future, she defaults to death. Indeed, to Sethe, “the future was a matter of keeping the past at bay. The “better life” she believed she and Denver were living was simply not that other one” (42). She is thus a model for Kierkegaard’s definition of the “sickness unto death.” For Kierkegaard, despair is a spiritual problem; it describes the condition of people who are not rightly related to themselves, who do not really have a self. It is important to point out that Sethe’s murder of her baby daughter only activated a deeper despair that had been there all along. Kierkegaard gives an example of a woman who has lost her lover; the loss merely reveals the self she never had:

This self of hers, which if it had become “his” beloved, she would have been rid of, or lost, in the most blissful manner—this self, since it is destined to be a self without "him," is now an embarrassment; this self, which should have been her richesse—though in another sense just as much in despair—has become, now that "he" is dead, a loathsome void, or a despicable reminder of her betrayal.”[19]

Sethe, had her daughter lived, would have still been living in despair (thinking of her children as her only good thing) but would have been a step further removed from ever discovering it.

The consciousness that one is in despair is the beginning of the way out of it, but no such recognition has been available to Sethe for eighteen long years. Her best hope for spiritual healing—receiving Baby Suggs’s lessons on loving one’s own self—was lost when Baby Suggs gave in to her own despair, a situation that the narrator points out in the opening pages: “Suspended between the nastiness of life and the meanness of the dead, she couldn’t get interested in leaving life or living it, let alone the fright of two creeping-off boys” (3–4). This suspension is the condition that Kierkegaard describes as the living death of despair: “despair is the sickness unto death, this tormenting contradiction, this sickness in the self; eternally to die, to die and yet not to die, to die death itself.”[20]

To keep people in a living death is the oldest goal of the demonic.[21] And this ghost is remarkably successful with that task until Paul D shows up. Paul D’s appearance is an immediate threat to the ghost because he represents the possibility of Sethe’s healing from despair—her hope for movement, growth, change—in short, new life. This potential new life for Sethe begins where it must, by Paul D’s simple expressions of love and care for Sethe that make her believe that she might be able to muster the courage to begin the pain of remembering (both her vicitimization and her own violent acts) that will finally begin her healing process. In the tender acceptance of his embrace, she wonders if “maybe this one time she could stop dead in the middle of a cooking meal—not even leave the stove—and feel the hurt her back ought to. Trust things and remember things because the last of the Sweet Home men was there to catch her if she sank?” (18). The ghost pitches the house in protest. This is going to be a battle.

Initially Paul D wins that battle, and overcomes the ghost’s power by coaxing Sethe and Denver out of the seductive trap of 124 and into the community’s participation in a carnival. As Susan Corey points out, Morrison’s use of the carnival here clearly suggests the positive grotesque as illuminated by Bakhtin.[22] Carnival represents everything that Sethe does not have: activity, fun, community, change, and new possibilities. Carnival celebrates a common humanity; it is the place where we laugh at ourselves, especially at our embodied existence. In this way, carnival epitomizes the positive grotesque, exaggerating the fact that our bodies are always changing, growing, transforming. Thus, as Bakhtin emphasizes, the laughter of carnival is productive; emphasizing sexuality and birth, it is “always conceiving.”[23] This carnival spirit enters Paul D, Sethe, and Denver. Paul D can come into their lives as a productive father, with new energy and growth—a possibility at first only adumbrated by the shadows of the three walking together. Their shadows are holding hands behind them on the way there, then leading them on the way back, suggesting that this new future is now within reach. “Nobody noticed but Sethe and she stopped looking after she decided that it was a good sign. A life. Could be” (47).

Since real life is the only thing that can loosen the grip of a living death, the ghost must now act more aggressively to keep its control. By the time the three get home from the carnival, it has emerged from the water, a fully grown woman now, and meets them at the house. The event is powerfully grotesque in its affront to readers’ expectations. When we witness Sethe’s sudden urge to urinate in a way that suggests her water is breaking, we know that Beloved is meant to represent the lost baby. But what is not immediately apparent to Sethe or to readers is whether this being is there to do good or evil. But readers quickly find out the answer to that question when Beloved begins to act in conventionally demonic ways. As René Girard explains, the devil can only be a parasite on being, one that functions by seducing its victims into making their own bad choices.[24] And right from the start, this ghost’s mode is seduction. It does not break in; it gets itself invited in. It gets itself fed and nurtured by promising love and attention. Its seductive power becomes most apparent in the way it has its way with Paul D, breaking up the potentially life-giving relationship between him and Sethe and moving him slowly out of the house, room by room.

But as powerful as this demonic ghost is, its power is markedly less than that of the divine because it cannot give or produce. It can only take away or destroy. Its power is like that of a vampire: it sustains itself on the lifeblood of others. The shared characteristic of all demonic grotesques is that they cannot act authentically but can act only by way of imitation. Beloved fits Girard’s definition of Satan in that its methods are necessarily mimetic. “Satan does not ‘create’ by his own means,” Girard writes. “Rather he sustains himself as a parasite on what God creates by imitating God in a manner that is jealous, grotesque, perverse, and as contrary as possible to the upright and obedient imitation of Jesus. To repeat, Satan is an imitator in the rivalistic sense of the word. His kingdom is a caricature of the kingdom of God. Satan is the ape of God.”[25] Beloved clearly apes the Christian God in order to rival God and to keep Sethe from healing. The demon becomes flesh, promises a biblical and pure love reminiscent of that from the Song of Songs, and seduces Sethe and Denver to form a perverse trinity with it. But because this anti-divine is ultimately in service to the divine, the demonic plan backfires.

Aping God: Incarnation

It is easy to see why some critics have argued that Beloved functions as a kind of Christ-figure in the novel. She is spirit become flesh, and her incarnation does, after all, ultimately lead to Sethe’s healing. But I think that it is more accurate to argue that Morrison offers Beloved as the ape of God, as a demonic being that tries the same strategies but desires completely opposite ends. There are two aspects of the incarnation of Christ that Beloved’s incarnation controverts to try to keep Sethe from healing: the acceptance of the body and the acknowledgment of the reality of time in human redemption.

First, when God chooses to become man in the incarnation of Christ, the action itself validates the beauty of creation, indicating that all human flesh has value. In short, it is God’s primary way of calling his people Beloved—in soul and in body. The theology of the incarnation has thus been the Christian Church’s answer to the western tendency toward Gnosticism—separating the soul from the body and valuing only the soul. Beloved implicitly argues that slavery as an institution is anti-Christian and essentially Gnostic because the body is seen only for what it can do or accomplish—not for having value in and of itself, simply because the person is made by God. When Baby Suggs preaches in the Clearing, she is preaching against the degradation of slavery by insisting on the spiritual value of the body. She insists that because the community cannot rely on others putting value on their flesh for itself, they must learn to do so themselves:

No, they don’t love your mouth. You got to love it. This is flesh I’m talking about here. Flesh that needs to be loved. Feet that need to rest and to dance; backs that need support; shoulders that need arms, strong arms I’m telling you. And O my people, out yonder, hear me, they do not love your neck unnoosed and straight. So love your neck; put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up (88).

In the theology of the incarnation, it is human flesh as well as spirit that has value and should be loved and cherished. Emily Griesinger thus turns to Baby Suggs’s sermon in order to reply to critics who argue that Morrison’s work is more pagan than Christian. “Not typically Christian in its emphasis on the holiness of the flesh, Baby Suggs’ sermon is genuinely Christian nevertheless in understanding that salvation includes the body and in recognizing that God does not look on outward appearance but penetrates the heart.”[26]

Second, Christian theology teaches that God, an eternal being, had to cross incongruously (and grotesquely) into time in order to redeem humanity. Jesus’s literal suffering, death, and resurrection are essential to the insistence that salvation for the Christian is never symbolic. In other words, the Christian conception of time is linear, not cyclical. Human redemption requires the passing of time; it requires that the redeemed one’s past action can remain in the past, and not be held against her. But Beloved, as a demonic force, is a vampiric, undead being whose goal is the exact opposite of God’s. Her task is to convince Sethe that time is cyclical and that she can never be truly free from the pain of her past except in death. She is trying to convince her to reject her own embodied existence completely in order to become free. Since this is the lie that Sethe already believed (proven when she killed her baby daughter in order to see her free), it is one that the demon has little difficulty seducing her with again.

This two-part demonic seduction can be seen in the section in which Beloved’s voice is made identical to those of the victims of the middle passage. All of these bodies are dead now, but their souls seem to live on, on the other side, existing in a place that sounds a lot like a conventional description of the eternal torments of hell. “All of it is now it is always now there will never be a time when I am not crouching and watching others who are crouching too I am always crouching the man on my face is dead” (210). Beloved’s goal is to seduce Sethe to achieve “the join” with her, which sounds like sexual union that will efface all individual identity.

I follow her we are in the diamonds which are her earrings now my face is coming I have to have it I am looking for the join I am loving my face so much my dark face is close to me I want to join she whispers to me she whispers I reach for her chewing and swallowing she touches me she knows I want to join she chews and swallows me I am gone now I am her face my own face has left me I see me swim away a hot thing (213).

Sethe’s beloved daughter is dead, we must never forget. For Beloved to act in this world she has to drain life from someone else. Thus the “join” of Sethe with this Beloved can ultimately only be the join of death, not of life. And Sethe, living in utter despair, is ready and willing to go down to this death. She thinks that she is taking Baby Suggs’s advice to “lay it all down, sword and shield” and live, but really she is moving toward death, as she tells Beloved:

When I put that headstone up I wanted to lay in there with you, put your head on my shoulder and keep you warm, and I would have if Buglar and Howard and Denver didn’t need me, because my mind was homeless then. I couldn’t lay down with you then. No matter how much I wanted to. I couldn’t lay down nowhere in peace, back then. Now I can. I can sleep like the drowned, have mercy. She come back to me, my daughter, and she is mine. (204)

The “peace” that she can have now can only come at the cost of choosing not to live, not to struggle. Beloved’s ultimate aim is to get Sethe to go all the way with her despair—to lock herself in the house and starve to death.

But as powerful as the demon’s seduction is, it is in this aping of the incarnation that the demonic sows the seeds of its own destruction and ends up serving the divine—and all because of the logic of the grotesque. The incarnation of Christ is grotesque because its shocking connection of human and divine is necessarily revelatory. In the incarnation, ultimate good appears in human form, healing and blessing. It reveals love. It shows the way and does it; it does not just teach about it. Likewise, Beloved’s very appearing ensures that eventually she will be seen for what she is: a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

And most important, it is in its grotesque insistence on incarnation that Beloved as ghost most parallels Beloved as text. When an interviewer told Morrison that her books had a haunting quality, Morrison was delighted. She wants her fiction to demand active participation from readers, like the call and response of black preaching. “I want a very strong visceral and emotional response as well as a very clear intellectual response,” she explained.[27] The logic of the grotesque in fiction, in other words, is inherently incarnational precisely because it insists that one’s intellect cannot be separated from one’s bodily experience. As Geoffrey Galt Harpham argues, the grotesque appeals to the parts of us that know instinctively that we cannot just vault over real pain and suffering by an act of will. The grotesque heals “the self divorced from the raw material of life and provid[es] a tonic affirmation of the wholeness of existence . . . [I]t is one of the large paradoxes of wholeness that it cannot be imagined or figured except as a violation of natural laws, in monstrous or distorted form.”[28]

Morrison turns to the grotesque because she wants her readers to enter the pain of Sethe’s past experiences as much as she wants Sethe to do so. It is a shock to anyone’s efforts to deny the impact of America’s slaveholding past as much as it is to Sethe’s denial of her own past. But the shock is also what makes experience thoroughly redemptive. For although the grotesque brings the real pain of Sethe’s past and the “60 million and more” victims of slavery to life, it also thereby proves that these past sins will ultimately fail to destroy Sethe and the African American community. Through the demonic grotesque, the past makes the redemptive “mistake” of drawing attention to itself, revealing the evil, injustice, and suffering for all to see. Theologically considered, the grotesque teaches us that evil can be more easily rejected when it is more clearly seen. When it appears so boldly, the community will no longer be able to ignore it; this is the truth to which Ella attests when she explains why she went on to participate in the exorcism at 124: “Whatever Sethe had done, Ella didn’t like the idea of past errors taking possession of the present. Sethe’s crime was staggering and her pride outstripped even that; but she could not countenance the possibility of sin moving on in the house, unleashed and sassy” (256). When the demon is forced to be sassy instead of seductive, we know its time is nearly up.

Editorial Statement: This excerpt comes from Christina Bieber Lake's forthcoming (October 2019) Beyond the Story: American Literary Fiction and the Limits of Materialism. It is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. Excerpts from other ND Press titles can be found here.

[1] A version of this chapter first appeared as “The Demonic in Service of the Divine: Toni Morrison’s Beloved,” South Atlantic Review 69, no. 3–4 (2004): 51–80; For an excellent overview of the complex topography of postsecular scholarship in literary studies, see Corrigan, “The Postsecular and Literature.” “By far the most agreed upon aspect of the postsecular is that, in some way or other, it includes both the secular and the religious. But scholars differ on how the two do or should relate to each, and on whether they remain distinct.”

[2] Fessenden, Culture and Redemption. Roger Lundin argues that Fessenden simplifies religious motives because the goal of the book “is not to laud the liberty of secular experience but to expose the poverty, even the venality, of secular Protestantism, which has sold its ethical soul for the sake of its subtly concealed cultural control.” Lundin, “Review of Culture and Redemption,” 106.

[3] In his review of the book, Timothy Aubry writes that “McClure is so intent on establishing the appeal of the postsecular by distinguishing it from traditional, dogmatic, fundamentalist religious practices and beliefs that his central concept at times runs the risk of losing its positive content, becoming merely a container for prevailing academic values with a vaguely spiritual inflection” (492). He continues, “The absurdity of religious orthodoxy is assumed rather than argued in his book, which is unsurprising given his audience, but this stance is somewhat ironic in light of his reflexive embrace of certain academic orthodoxies whose axiomatic status a study of postsecular thought might be a good place to question or at least rethink” (493). Aubry, “Partial Faiths.”

[4] McClure, Partial Faiths, 14. Yes, it certainly does resemble Hazel Motes’s Church Without Christ.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 128.

[7] Hungerford, Postmodern Belief, 105. For Hungerford, this authority is necessarily at the vampiric expense of biblical authority, for the effort is to make the literary text a substitute for scripture.

[8] Morrison, Beloved, 1. Subsequent citations appear parenthetically in the text.

[9] Morrison and Taylor-Guthrie, Conversations with Toni Morrison, 226.

[10] Morrison found a literal ghost no more incredible than the political realities illustrated in her novel: “The fully realized presence of the haunting is both a major incumbent of the narrative and sleight of hand. One of its purposes is to keep the reader preoccupied with the nature of the incredible spirit world while being supplied a controlled diet of the incredible political world.” Morrison, “Unspeakable Things, Unspoken,” in Solomon, Critical Essays on Toni Morrison’s Beloved, 92.

[11] Trudier Harris-Lopez begins with this observation and discusses the implications of gendering the demonic as female. Harris, Fiction and Folklore, 151–64.

[12] Grotesques “body forth the threatedness of human existence, whether in terms of moral temptation, spiritual failure, or physical catastrophe. Encroaching evil, natural or human, is their recurring theme” Hazelton, “The Grotesque, Theologically Considered,” 78.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Susan Corey argues that Beloved embraces both a positive and a negative grotesque, in that “the grotesque not only reveals the horror of slavery, but it also sets forth a vision of regeneration and healing.” Corey, “Toward the Limits of Mystery,” 33.

[15] Gurleen Grewel argues that “in a way it is important that Beloved remain somewhat inaccessible and mysterious so as to be a suggestive symbol of the unconscious, of desire, of the past, of memory—for none of these is fully graspable by the conscious mind.” Grewal, Circles of Sorrow, Lines of Struggle, 116.

[16] Morrison and Taylor-Guthrie, Conversations with Toni Morrison, 85.

[17] Ibid., 116.

[18] Solomon, Critical Essays on Toni Morrison’s Beloved, 39–42.

[19] Kierkegaard, The Sickness unto Death, 50.

[20] Ibid., 48.

[21] Augustine contrasts the devil, who is the mediator of death, with Christ, who is the mediator of life. St. Augustine, The Trinity, 162.

[22] Corey, “Toward the Limits of Mystery,” 38.

[23] Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 21.

[24] Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, 32–46.

[25] Ibid., 45.

[26] Griesinger, “Why Baby Suggs, Holy, Quit Preaching the Word,” 694; original emphasis.

[27] Morrison and Taylor-Guthrie, Conversations with Toni Morrison, 147.

[28] Harpham, On the Grotesque, 54–55.