When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.

―Viktor E. Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning

This academic year educators are finding the intellectual and interpersonal dynamics of their classrooms radically reframed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to reimagined classroom spaces and the development of hybrid models of course delivery, strategies which seek to mitigate the potential for infection in the classroom, COVID’s greatest impact upon education might be the manner in which it couples the learning experience with an acute awareness of death and dying as an imminent—and not merely abstract—reality.

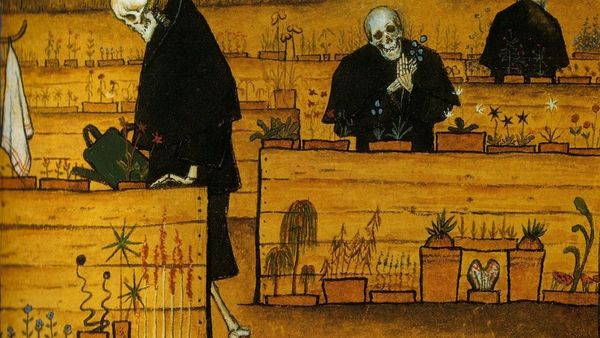

For the humanities, grounded in the “burial” act of its latin root humando, death hovers implicitly around the classroom already: to ask what it means to be human across history is to ask what it means to be mortal. The pedagogical dilemma, of course, is convincing students the fundamental questions of our disciplines bear meaning not merely for “man in general” but for the inner recesses of our individual selves.

We can very easily claim to know we are mortal—“Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal”—without ever recognizing the claims such truths place upon our lives. But the shift from syllogistic assent to epiphanic conviction does not come easy. To be sure, death’s emergence as an imminent possibility is by no means the only way to awaken the unreflective self to the meaningfulness of humanistic inquiry. Yet it might be the most effective. “The prospect of death,” Dr. Johnson writes, “wonderfully concentrates the mind.”

As such, the imposition of awkward pandemic protocols in the classroom—the transformation of learning through a liturgy of sanitization, social-distancing, and masked discussion—offers an unusual opening for educators to recover the urgency of their subjects by the light of mortality rather than the traditional quietude of contemplative autonomy.

The benefit of confronting death within the classroom was made clear to both of us this past spring when we co-taught an undergraduate course on “Death and Dying in Literature” just as the pandemic began to spread. As a course which foregrounded literature’s treatment of death across genres and time-periods, our class became an intermediary space wherein the mounting panic surrounding the pandemic could be considered through the prism of literature. By the time the coronavirus death-toll became a daily headline in mid-March, our students had already ventured into the underworld with Odysseus, considered the “wisdom” of the cemetery with the Graveyard Poets, and occupied Auschwitz alongside Viktor Frankl.

The evolution of death from narrative topos to subjective reality, spurned by the confluence of a global pandemic and honest classroom conversations, brought death to life for each of us in powerful ways. Far from death-denying Don Juans, as David Randell of the National Association of Scholars recently dubbed today’s college students, our students faced death with a disquieting calm. They were at once sensitive to the shape-shifting presence of death within both life and literature while suspicious of anyone claiming to outmaneuver it. In short, our students were more Prufrock than Poe in their dispositions toward human mortality. Death was not a complex riddle that could be resolved through analysis, as detective Auguste Dupín contends, but more of an “eternal Footman” standing by as we conducted class.

The explicit presence of death reinvigorated our readings in unexpected ways. If the day-to-day death tolls of a pandemic era depersonalize death by reducing it to mere data, literature enlivens death as a felt reality that demands a response rather than remote reflection. The stories we read, the poems we discussed, the very words on the pages before us became a living picture of suffering and death; simultaneously, and so markedly at odds with the statistical rendering of death on the screens surrounding us, they were balm to our wounded souls, reminding us of the dignity and beauty of life.

While Dante had Virgil to lead him through a terrain in which “death so many had undone,” William Styron and C.S. Lewis were our initial guides as we and our students grappled with our own complex reactions to the growing pandemic death tolls around us and the requisite disconnection embedded into remote learning. Styron and Lewis’s intimate engagements with depression, grief, and mortality gave us language to describe our own shared and solitary grief.

In his 1989 memoir Darkness Visible, a bracing account of his battle with depression, Styron recalls a “murky distractedness” and a “failure of mental focus and lapse of memory” that seems a snapshot of our times. The routine pleasures which once punctuated his day—a well-prepared breakfast, an unread newspaper—are sullied by feelings of “panic and dislocation” that emanate from a crippling sense of “being engulfed by a toxic and unnameable tide that obliterate[s] any enjoyable response to the living world.”

Grief, while less amorphic than depression, similarly unsettles the routines which tend to order our lives. Grief frustrates the habitual, Lewis notes in A Grief Observed, disrupting those routines which once lent meaning to our lives with a “ghastly sense of unreality.” Our students empathized with Lewis, who clung desperately to his sorrow, unwilling to “return to normal” after his wife’s death, unable to rebuild his “house of cards.” In the final section of his observations, Lewis admits that when he began writing he misunderstood the nature of sorrow. He writes, “I thought I could describe a state; make a map of sorrow. Sorrow, however, turns out to be not a state but a process.” His grief, he finds, is not something to “get over” or move beyond. It is, rather, an “a universal and integral part” of his “experience of love.”

Lewis’s grief shatters his ideas about love, about reality, about God. But this shattering, he comes to realize, is actually a reminder of God’s presence, not of his absence. After all, it is God himself who does the shattering. Daily—minutely—we find ourselves worshipping our idea of God, not God himself. And he, in his goodness and grace, obliterates that idea. Not for his sake, but for ours. Not to find out the quality of our faith for himself, but to reveal the quality of our faith to us. Lewis writes, “He always knew that my temple was a house of cards. His only way of making me realize the fact was to knock it down.” Moving through the crucible of grief and doubt, Lewis returns to rest in faith. He holds in tension these two truths: death is “even more inexorable . . . than our severest imaginings can forbode” and, nevertheless, “all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

For the rest of the semester, Lewis became a focal point for our students, an epiphanic voice that woke our students up to their own sorrow and the world’s sorrow. Through agonizingly honest observations of his grief, Lewis resuscitated an abstract truth that had suddenly become very real to each one of us: death’s inevitability, far from rendering meaning absurd, demands that the search for meaning become the central focus of each of our lives. One need not be an educator to appreciate the enthusiasm of a young mind awoken to the meaningfulness of life.

When we asked our students to reflect on death and dying at the end of the term, we were met with perspectives that restored meaning to mortality. Alongside Dickinson, Dostoevsky, and Donne, each student glimpsed in death something more than mortal ruin. “Death acts as a shock to our dull senses,” one student wrote in her exam, “and this shock pushes us beyond reason into a transcendent realm where reality is experienced more as an epiphany than an explanation.” The epiphany of reality—including that of our newly masked and socially distanced reality—our students determined, entails living more intentionally, more empathetically.

The risk remains, however, for death to descend back into abstraction: a concept to map rather than a reality we must learn to live meaningful lives in light of. This risk is perhaps heightened rather than diminished now that there are a number of viable vaccines looming, carrying with them the flickering promise of life returning to normal.

With most of our students now occupying half-empty classrooms amidst a pandemic that seems less of a panic than a pain, death is less pressing than the present week’s deadlines. The ominousness of our masks, even, has softened into a fashion accessory. “How thoroughly departmental,” Frost reflects, death becomes in the hands of the living.

While we as educators seek to train students to discern what is meaningful within our disciplines, we seldom (if ever) anticipate the moments in which meaning emerges to make a holistic rather than a syllogistic claim upon us. Such moments hinge upon truths which exceed any syllabus. By welcoming mortality into our classroom, we invited our students to combat the nihilism and depression that permeates our culture’s response to the pandemic. We invited them to cultivate hope in the one who has promised that he is coming to defeat even death. We invited them to glimpse the immortal importance of their day to day lives. And that is not so grim an encounter to court.