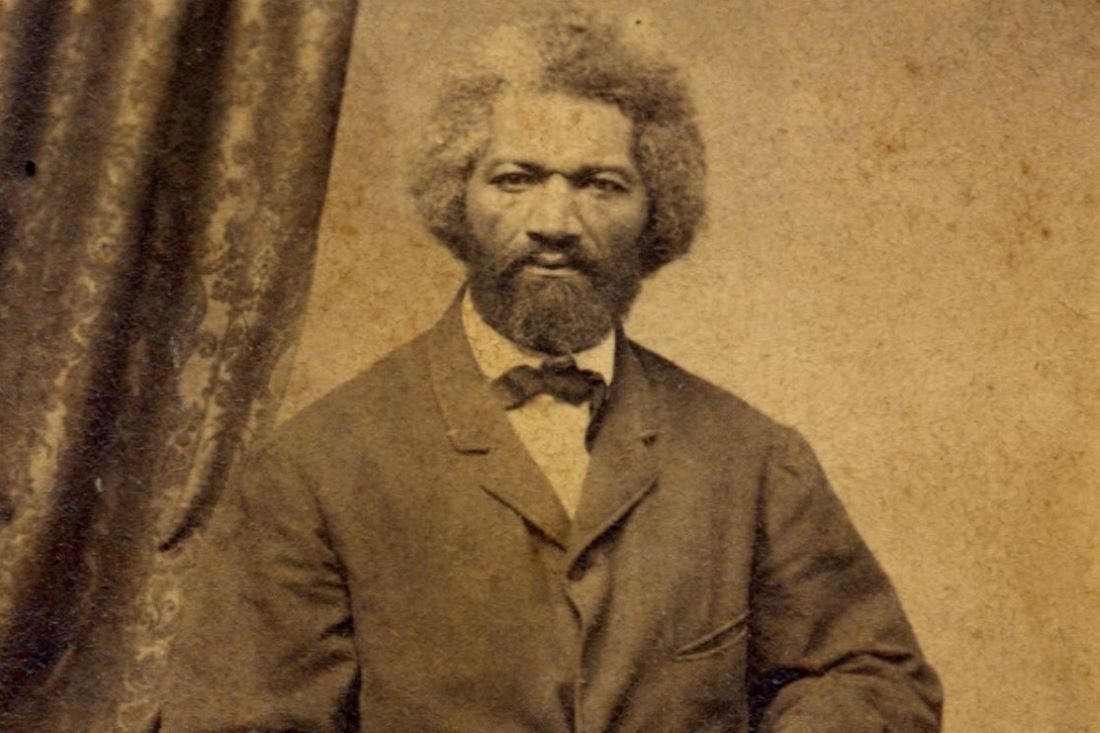

Human dignity is at the heart of Black politics. Claims to dignity circulate widely in Black activist spaces today, including in the first line of the Movement for Black Lives platform. This emphasis on dignity is nothing new. In the most influential piece of nineteenth-century Black writing, Frederick Douglass’s recognizes human dignity at the decisive turning-point in his autobiography.

An enslaved boy of sixteen, Douglass is loaned out by his owner to a notorious slave-breaker, Edward Covey. The man’s cruelty was so great, the violence he inflicted so grave, that Douglass ran back to his owner to seek protection. Unsuccessful in his appeal, Douglass must return to face Covey. At first, Covey acts as if nothing is the matter, ordering Douglass to begin his morning chores. Then, Covey sneaks up on Douglass and tries to tie his legs with a rope.

Douglass leaps. His legs elude the rope. For the first time in his life, he resolves to fight back. Covey tries again and again to capture Douglass, first alone and then by enlisting the help of others, but Douglass eludes capture and matches his blows. In the struggle, body grappling with body, Douglass no longer sees himself as Covey’s inferior. “I found my strong fingers firmly attached to the throat of the tyrant,” Douglass recalls, “as if we stood as equals before the law.”

As they struggle, Douglass can envision a world where he and Covey are equals. He also knows that world is foreclosed. Enslaved, living in world where Blacks have nothing approaching equality, the world Douglass envisions is wholly other from the world he inhabits. The more he struggles, the more he is motivated to pursue that world of equality, even as he knows it is impossible to chart a path from where he is to where he wants to go. After the fight, Covey will still rule over him. And yet, conjuring a world free of domination as he struggles, Douglass achieves his humanity. “I was nothing before; I was a man now.” He concludes, “A man without force is without the essential dignity of humanity.”

What Douglass depicts in this passage is the primal scene of domination. A master is defined by his ability to impose his arbitrary will over his slave. Domination requires dehumanization. For the master’s inclination toward domination to overcome his inclination to charity and empathy, he must employ a battery of lies that make his slave count as less than human. In fact, this is too much work for him alone; he depends on pseudo-scientific, pseudo-philosophical, and pseudo-theological ideas embedded in his culture, its laws, and its institutions in order to turn domination into common sense, to make the end of slavery seem irrational and impossible.

Those ideas that authorize domination infect not only Covey but also Douglass. Until he fights Covey, Douglass believed he was “nothing”—unworthy of humanity. Through struggle, at once bodily and psychic, Douglass comes to see the lies that authorized his domination, even if he cannot end that domination. In fact, Douglass gains something Covey lacks. Covey inhabits a world of lies. He accedes to these lies rather than struggles against them. Covey not only ignores Douglass’s humanity, he accepts a false image of himself as master, godlike—which is, in fact, a rejection of his own humanity.

Protesters marching under the banner of Black Lives Matter today claim that we must constantly refer to the primal scene of domination. Slavery has been illegal for a century and a half, but the set of ideas embedded in culture, norms, and institutions that made slavery plausible remain: anti-Blackness. Racial domination remains. The primal scene of slavery—one master commanding one slave according to his arbitrary will—never really existed, yet describing it accurately names the logic of domination at work in slavery, segregation, police violence, discrimination, and microaggressions. And in struggle: dignity comes in struggle against the various manifestations of anti-Blackness.

+

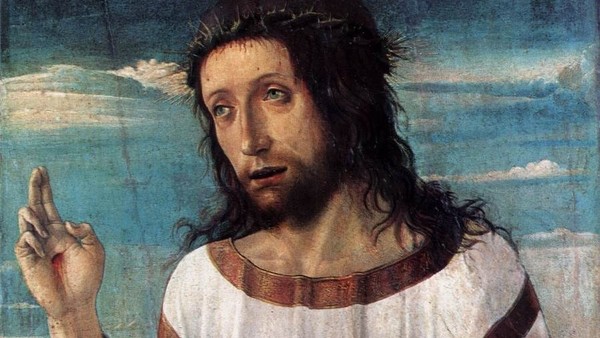

Augustine’s City of God is a story of domination. His Confessions is a story of struggle. We humans are under the sway of a libido dominandi, a will to dominate, to set ourselves up in the position of master. It is unquenchable. The more we set ourselves up as a master, the more we desire mastery—but of course mastery is impossible for a human in the world. We aspire to be gods, and we necessarily, catastrophically fail. At the end of the day, we are dominated by the will to dominate: our lives and souls become increasingly disordered as we pursue our caprices, turning further and further away from truth. We are ruled by pride, which stokes our false sense of mastery and control, and blinds us to a God who is greater than all of us, greater than the world, illegible from the world.

The will to dominate tempts us, causing discord in our selves, our communities, and our polities. But it does not have the last word. The will to dominate promises confidence and clarity, but we are creatures who doubt. Augustine’s Confessions is a celebration of doubt, of the fundamental opacity of our humanity—to ourselves, but not to God. When we think we are seeing things rightly, we must doubt more. As Jean Elshtain writes, the bedrock for Augustine is not “I think, therefore, I am” but rather “I doubt, therefore, I know I exist.” Doubting is one facet of the struggle that animates Augustine’s own journey, a struggle with himself that is really a struggle against domination, against the desire for mastery.

In his commentary On Genesis against the Manichees, Augustine turns to another primal scene of domination, in the Garden of Eden. As Augustine interprets Genesis, lust for domination and bodily lust blend into each other. The serpent promises that the forbidden, desired fruit will turn the humans into gods. They will know good and evil; in fact, they can define good and evil according to their whims. Augustine concludes that Adam and Eve “were persuaded to sin through pride,” by their desire to become gods. They came “to love to excess their own power.” But domination is no path to happiness, just the opposite. Human happiness will only be achieved when the will to dominate is renounced, allowing the human will to come into conformity with God’s will.

We live after the Fall, and our world is infected by domination. Recalling what happened in Eden reminds us that the will to dominate is unavoidable. But we also live with the promise of a world without domination, a world to come, across an unbridgeable divide from our present world. Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden is not the end of the story. We are promised new life conformed to truth. We are promised happiness that dazzlingly exceeds its hollow copies. We are promised freedom.

The two characters whose fight Douglass stages, master and slave, are both within our self. We are tempted by mastery. We are used to acceding to domination. But we are also capable of struggle. For both Douglass and Augustine, struggle involves psychic as well as bodily dimensions. For both, as we struggle, we realize our humanity as it images the divine. The world propagates false claims about who counts as a human and who does not, but the more we struggle against domination, the more we doubt the wisdom of the world. As we struggle, we realize we are more than what the world says we are; indeed, our humanity is inexpressible in the language of the world. As we struggle, therefore, we conjure (in song, poetry, and images, not prose) a world wholly other than the present, where the humanity of each is recognized as God recognizes our humanity today.

+

The language that is often used to speak about racism introduces a great deal of confusion. We talk about violence, oppression, marginalization, exploitation, and injustice. We talk about discrete wrongs that need righting and systems that need transformation. We talk about the value of diversity and the need to attend to cultural difference. We talk about the need to hear the voices of theologians and theorists speaking from their own distinctive cultural contexts.

We should be talking about domination. If Adam and Eve’s temptation by the serpent is what prelapsarian domination looks like, Douglass’s fight with Covey represents postlapsarian domination. In both cases, the animating force is the lust for mastery. The Middle Passage attempts to literalize mastery: completely extinguishing the connections between a slave and her family, language, and culture. Where Adam and Eve succumbed to their own desires and lost the opportunity to realize their humanity, the postlapsarian world is interminably struggling against itself, the will to domination (Covey) attempting to subdue the spirit of humanity (Douglass) and so quash hope for freedom, for life lived in truth.

It is tempting to end here, with irreducible complication and interminable strife. But Douglass’s narrative not only teaches lessons about domination in general, it instructs us about one very specific system of domination. When we look at a world, rather than a garden, we find individuals formed in communities; we find the will to domination infecting communal practices, norms, and institutions in addition to an individual’s mind and body. For a community to be infected by domination is to be able to tell a story about how a particular primal scene of domination explains multiple ills of that community. In other words, we must theorize a disease (a species of domination) to explain the symptoms (instances of oppression, marginalization, injustice, etc.). Anti-Blackness, the species of domination rooted in the primal scene of African slavery, explains the varied ailments experienced by Black people today. (Similarly, we might posit rape as the primal scene of patriarchy, indigenous genocide as the primal scene of settler colonialism, and so on.)

The varied ways that anti-Blackness expresses itself can seem remote from the libido dominandi, and talk of systemic racism emphasizes a level of abstraction that precludes locating an errant will. Housing and employment discrimination, educational and medical inequities, and the disproportionate exposure of Black people to environmental hazards all seem far removed from a desire to dominate. Racist comments and microaggressions seem to flow more from ignorance than malicious desire. Perhaps police violence against Black people grows out of toxic police cultures, but that seems distinct from the will of a white person to dominate a Black person.

Yet historians and sociologists (and even more importantly, writers and artists) have produced an overwhelming body of evidence demonstrating that discrimination, inequities, police violence, and everyday racism against Black people flow from the legacy of slavery. Even Frederick Douglass himself is engaged in this work: he mapped his own, complex experiences onto the primal scene of domination through writing his narrative. After all, it was not simply Covey against Douglass. Covey was standing in for Douglass’s owner, who himself was standing in for the system of slavery as a whole, a system that was not isolated to those who legally owned slaves but that warped a whole community. Douglass, too, did not struggle alone; he was aided directly and indirectly by other enslaved people with whom he lived. Even with all these complications, it still makes sense to talk of the will to dominate and the struggle against domination as Douglass fought Covey.

Put another way, each of us is formed in a community infected by various systems of domination. This channels our will to dominate, to find law and order for ourselves at the expense of others. Simply identifying and struggling against our own will to dominate, in isolation from systems of domination, is an inadequate response. The power that systems of domination have to stoke and direct our will to dominate would overwhelm any of our individual efforts. This is a facet of our fallen world. Struggle must be rightly oriented, not only against ourselves but also against those specific systems of domination that corrupt our community. The more struggle, the more clarity we achieve about the machinations of domination, and the greater the foretaste we receive of a world without domination—participation in the divine.

+

It can be tempting for progressive Christians, horrified at racist violence, to simply align themselves with protesters or to support demands for policy reforms. The Augustinian tradition emphasizes that dignity is achieved through struggle, but this struggle is at once bodily, psychic, social, and political. Domination, including anti-Blackness, infects all of these levels, in people of all races. Struggle must happen at all of these levels as well. And it must continue into the future, as far as we can see. Visioning what is beyond the horizon of worldly time, a world without domination, is essential for orienting struggle, just as that visioning work is made possible by struggle. Protest and policy change will not save the world; it is from the perspective of a redeemed world that we must discern the appropriate protest and policy change. That requires cutting through the obfuscations of domination, all the tricks that systems of domination use to conceal themselves.

James Baldwin—like Augustine, a preeminent theorist of the connections between bodily, psychic, and political domination—once wrote, “The thing that most white people imagine that they can salvage from the storm of life is really, in sum, their innocence. It was this commodity precisely which I had to get rid of at once, literally, on pain of death.” We all are formed in communities infected by domination, and we all participate in systems that dominate. But Baldwin’s suggestion, one that is common in Black thought and theology, is that those who feel the violence of domination most severely are due an epistemic privilege. Baldwin writes hyperbolically, conjuring another primal scene, but his point is intuitive. Those who face the full force of domination every day have particular expertise on domination. Those who are less severely affected by domination tend to be enraptured by the will to dominate, with its pretensions to innocence and, as Baldwin puts it, fantasies of “security and order.”

The epistemic privilege of the oppressed is defeasible; it is a fallen world, after all. But it helps to make sense of some of the claims of Black theology that can seem outlandish. Theology must start from the perspective of Blacks. Which is to say, those who have the most reason to doubt the wisdom of the world, who are least captivated by the libido dominandi, ought to serve as guides to Christian thought and practice. Black dignity is the paradigm for human dignity.