Mark Twain, in his travel novel Innocents Abroad (1839), records a characteristically ironic description of the “tomb of Adam” in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Having spoofed the “veracity” of the tomb and the credulity of guides and visitors alike, he exclaims:

The tomb of Adam! How touching it was, here in a land of strangers, far away from home, and friends, and all who cared for me, thus to discover the grave of a blood relation. True, a distant one, but still a relation. The unerring instinct of nature thrilled its recognition. The fountain of my filial affection was stirred to its profoundest depths, and I gave way to tumultuous emotion. I leaned upon a pillar and burst into tears.[1]

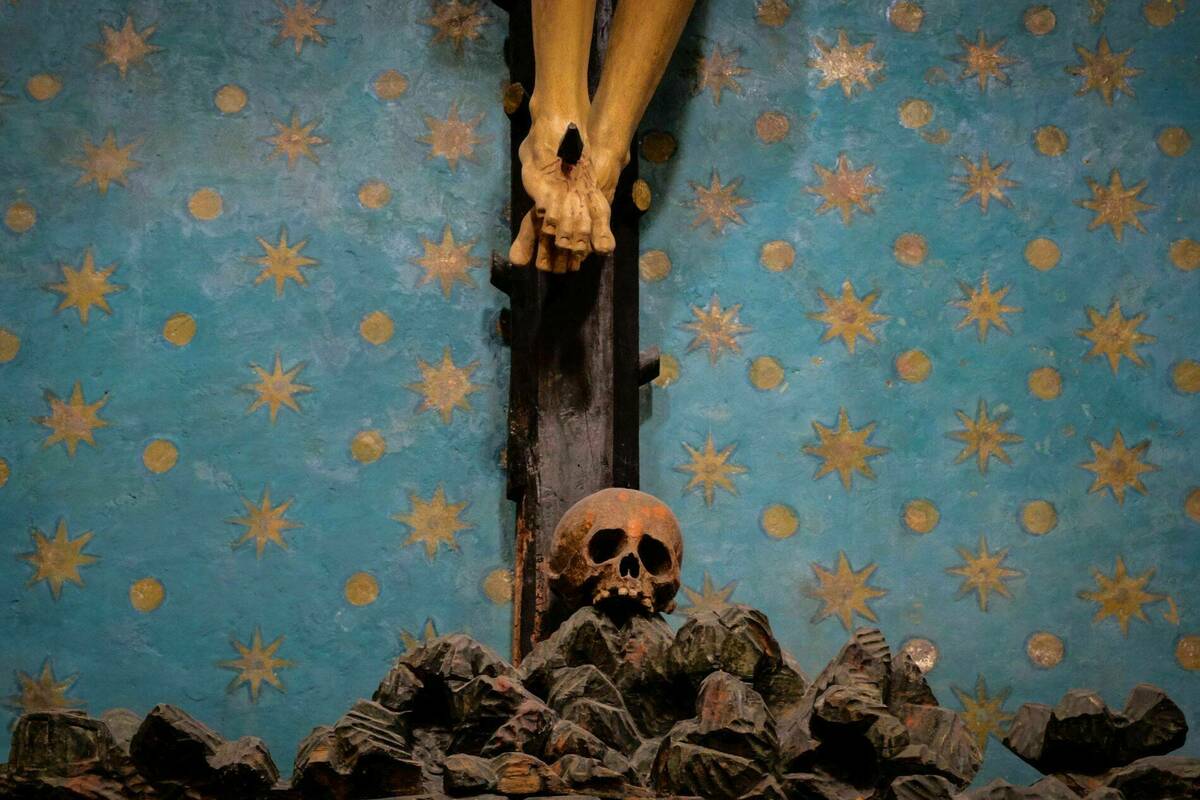

Last spring, entering the Holy Sepulcher for the first time, I felt none of that tumultuous thrill of recognition as I stepped into the quiet, unadorned, and unfrequented chapel that claims to house the bones of that “blood relation.” As crowds of pilgrims hurried to venerate the rock of Golgotha in the chapel above, I gazed at the crack in the wall where a reddish hue lingers from the blood that ran down from a Cross and onto the skull of the first created human being—or so the legend goes.

Dating in some form to the seventh century, the Chapel of Adam lies directly beneath Golgotha, built into and around the cracked stone that forms the hill where the Gospels record the crucifixion and death of Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews. This spot has been associated with the burial of Adam in Christian tradition since at least the fourth century. The difficulty of verifying where the bones of the first human repose intensifies a common, lingering question surrounding sacred sites of pilgrimage: whether or not the geographical site is actually what devotion claims it to be.

Twain’s ironic credulity only half exaggerates the sincerity with which Christian pilgrims—ancient and modern—venerate the sites of the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth. As I encountered such sacred and contested sites in and around Jerusalem, the tension between devotional claims and historical veracity was inescapable. Was this the place where Jesus was arrested, or imprisoned, or crucified? Was this the place of Adam’s burial? How can we know? And what difference does it make if we can or cannot know with perfect authority the historical veracity of a site?

The Chapel of Adam—a devotionally prompted space about a legendary figure—offers a perfect case study to explore how historical veracity and theological claims intersect in sacred space. Tracing the earliest sources of the chapel’s emergence in writing and architecture shows that early and medieval Christians were interested in questions of geography and history. Yet they were more interested in the fact of redemption accomplished by Christ and efficaciously encountered in the liturgy. The question of historicity is revealed as secondary to the true and efficacious work of the Cross accomplished in the liturgy. Thus, the legendary and architectural conflation of the burial place of Adam and the Crucifixion renders visible the central Christian understanding of what the Cross effects and liturgy renders participable: the salvation of all humanity.

Tracing the Beginnings: Scriptural Sources and Jewish Traditions of Adam’s Burial

How did the association between Adam’s burial and Golgotha emerge? It begins, however dimly, in Scripture: all four Gospels record that Jesus was crucified at Golgotha, the “place of the skull” (Matt 27:33; Mark 15:22; Luke 23:33; John 19:17). The gospels give this enigmatic place-name, clearly well known, without comment or explanation. It is in Origen (185–254 CE) that we find the first textual witness that explains the “skull” as Adam’s.[2] In his commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, he claims that a certain “Hebrew” tradition tells that “the body of Adam, the first man, is buried there where Christ was crucified, so that ‘as in Adam all die, just so in Christ all shall be made alive’ (1 Cor 15:22).”[3] Explaining the toponym “place of the skull” inspires a connection between the burial place of Adam, the first human being, and the place of the redemptive death of Jesus who “died for all humanity.”[4]

Origen famously refers to a “Hebrew” source for his claim that the explanation for the “place of the skull” was the burial of Adam. This seems to be a compelling strand to support a verifiable geographical claim: Christians inheriting a Jewish memory. Yet recent scholarship by Jordan Ryan and Sergey Minov have convincingly shown that the earliest evidence of Jewish traditions of Adam’s burial are contemporary with Origen. Ryan suggests that “there is no evidence from Jewish sources prior to the third century that would corroborate Origen’s claim about its ‘Hebraic’ origins.”[5]

Further, even if Jewish tradition had pre-dated Origen’s writing, the complicated witnesses in the multifaceted landscape of early Judaism make identifying one single “Jewish” tradition impossible. As Gary Anderson has shown, the figures of Adam and Eve attracted vibrant attention and elaboration in both Jewish and Christian textual traditions.[6]

Thus, Jewish tradition witnesses to at least four possible locations for the burial of Adam. One tradition locates Adam’s tomb at the cave of Machpelah in Hebron (in a place known as the Kiryat Arba, the “city of four”), where Adam and Eve form a fourth patriarchal pair to Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah.[7] Other (late rabbinic) sources locate Adam’s burial on Mount Moriah, which they identify as the center of the world.

In addition to geographically identifiable burials in concrete places (Hebron, Mount Moriah), other Jewish traditions place the burial of Adam in or around Paradise: the Greek Life of Adam and Eve locates the burial in Eden where Adam was created, returning to the same dust from which he was made (Gen 3:19).[8] A similar tradition in the book of Jubilees locates Adam’s burial by his descendants outside Paradise, where (according to Jubilees) Adam was created and spent forty days before entering Eden.[9] Interestingly, Jubilees names Adam as the “first to be buried in the ground,” sharing with the Life of Adam and Eve a tradition that Abel—the first human to die—was not interred until after Adam had died.[10]

Ultimately, these divergent sources share a central concern for the exegesis of Scripture (here, Gen 3:19) and an incorporation of Adam’s life and death into a broader narrative of creation. Neither unfounded fantasy nor strict historical factuality, the early Jewish narratives of Adam’s burial are rich sites for reflection on Scriptural account of human mortality and creation.

Beginning Again: The Burial of Adam in Christian Textual Tradition

If we cannot follow Origen in claiming Jewish tradition as the authority for Adam’s burial at Golgotha, we must turn to early Christian sources for the earliest evidence of the tradition. Like the Jewish sources, early Christian authors read Adam’s death in light of creation in Eden and the mortality occasioned by the Fall. But, in a key difference, Christian authors read Adam’s death and burial through the lens of redemption accomplished in Jesus Christ. This focus emerges forcefully in three important witnesses to the early Christian textual tradition of Adam’s burial: Jerome, Epiphanius, and Basil of Caesarea.

Jerome (347–419 CE) is the most complicated early Christian witness to this tradition. In his commentary on Ephesians (ca. 387 CE), he specifically rejects the Golgotha tradition for Adam’s burial, instead affirming a Jewish tradition of Adam’s burial at Hebron, in the cave of Machpelah.[11] Yet in a letter to Marcella dating around the same time (Epistle 46, ca. 386 CE), he repeats the tradition of Adam’s burial at Golgotha without comment.[12] This puzzling contradiction might be explained by the fact that this letter is written in the name of Paula and Eustochium—Jerome might simply be repeating a view that is not his own. Or, Jerome’s rejection of the Golgotha tradition of Adam’s burial might reflect his local Bethlehem-centered interest. As Brouia Bitton-Ashkelony has convincingly argued, Jerome is often hesitant to give any more attention to a sacred site in Jerusalem than is strictly necessary.[13]

Rather than forcing a choice between Jerome’s two expressed opinions, I suggest that attending the theological reasoning behind where he places Adam’s burial can harmonize his contradictory interpretations. His treatment of Adam’s burial emerged in reference to Ephesians 5:14 (“Awaken, sleeper, arise from death”), a text which emerged in reference to Adam’s burial at Golgotha very early in Christian tradition. Jerome repeats the connection between the crucifixion and Adam’s burial without comment in Epistle 46, but in his commentary on Ephesians, he scorns the suggestion Christ’s blood literally vivified the dead Adam.

Instead, for Jerome, the “place of the skull” referred to the fact that Golgotha was a place of common execution (Commentary on Matthew, ca. 398 CE). He insists that if anyone wishes “to contend that the reason the Lord was crucified there was so that his blood might trickle own on Adam’s tomb, we shall ask him why other thieves were also crucified in the same place.”[14] For Jerome, the “place of the skull” was a site of common, humiliating death that was transformed into a place of life through Christ’s crucifixion. Thus, “place of the skull” signifies the irony of the Crucifixion accomplishing a universal reversal of death in a place of common execution, rather than a specific reversal of Adam’s primordial death. Thus, even in his rejection of Golgotha as the site of Adam’s burial, Jerome expresses the same theological commitments which underly the Golgotha tradition: the reversal of sin and death through the Cross of Christ.

Another key witness to the association of Adam’s burial at Golgotha, less complicated than Jerome, is Epiphanius (310–403 CE), bishop of Salamis. In stark contrast to Jerome, Epiphanius emphasizes a graphic connection between Adam’s skull and the Cross in his Panarion (ca. 378 CE). Pursuing the same exegetical question that motivated Origen and Jerome, Epiphanius rejects the explanation of “Golgotha” through topography (the suggestion that a bare mound of stone might look like a skull). Instead, he asks why the place would be called “of the skull,” unless “the skull of the first-formed man had there and his remains were laid to rest there, and so it had been named ‘Of the Skull?’” Considering his rhetorical question answered, Epiphanius explains the significance of the conjunction:

By being crucified above [the remains of Adam] our Lord Jesus Christ mystically showed our salvation, through the water and blood that flowed from him through his pierced side . . . beginning to sprinkle our forefather’s remains, to show us too the sprinkling of his blood for the cleansing of our defilement and that of any repentant soul; and to show, as an example of the leavening and cleansing of the filth our sins have left, the water which was poured out on the one who lay buried beneath him, for his hope and the hope of us his descendants.[15]

For Epiphanius, the blood and water which pour forth from the side of Christ are a symbol of the redemption and cleansing offered not just to Adam, but to “any repentant soul” among Adam’s descendants.[16] Interestingly, in a later book of the Panarion he suggests that the “resurrection of the dead” mentioned in Matthew 27:53 began with Adam, betraying an unshakable conviction that the recapitulation of creation must also begin, somehow, with the first created human being.

Epiphanius witnesses to an important step in the growth of the tradition. Origen had connected Adam and Golgotha merely through reversal of Adam’s death by Christ’s own death. Epiphanius witnesses to the literal, graphic cleansing by water and blood dripping on the dead remains. This visceral connection through blood became increasingly ubiquitous in Christian tradition of Adam’s burial under the Cross (forming a conventional element in iconography of the Crucifixion to the present day). Further, Epiphanius explicitly connects Adam’s redemption with that of every repentant soul and sees the redemptive blood and water poured out upon Adam “for his hope and the hope of us his descendants.” The question of Adam’s burial is not a merely historical inquiry; it has direct significance for all humanity.

Our final textual witness to the Christian tradition of Adam’s burial on Golgotha in the fourth century is Basil of Caesarea (ca. 329–379 CE). In his commentary on Isaiah, relating a story from “unwritten tradition,” Basil narrates the expulsion of Adam from Paradise and settlement in Judea until his death, when the

sight of the bone of the head, as the flesh fell away on all sides, seemed to be novel to the men of the time and after depositing the skull in that place they named it Place of the Skull. It is probable that Noah, the ancestor of all men, was not unaware of the burial, so that after the Flood the story was passed on by him. For this reason the Lord having fathomed the source of human death accepted death in the place called Place of the Skull in order that the life of the kingdom of heaven should originate from the same place in which the corruption of men took its origin, and just as death gained its strength in Adam, so it became powerless in the death of Christ.[17]

Here, Basil does not repeat the tradition of Christ’s blood dripping on the skull of Adam seen in Epiphanius. Instead, he focuses on the graphic nature of human mortality, picking up strands common to a Jewish tradition that Adam settled in Judea after expulsion from Paradise. He meditates on the novel and unnatural shock of Adam’s death to a humanity who had so recently been in Paradise (strangely silent about Abel’s tragic end in Genesis 4:8).

Basil not only provides a witness to the tradition death and burial of Adam connected to Golgotha, but also offers a witness to early Christian concern with the transmission of the story itself. He answers a very reasonable question: how would the burial of Adam have been transmitted after the Flood? This parenthetical comment reveals an awareness of the fragility of human memory over time and in the face of catastrophe. It is not a question unique to Basil: Sergey Minov has recently traced several early Christian accounts which address the vexing question about how Adam’s body came to be under Golgotha through creative narratives.[18] The Jewish witnesses to the longevity of Adam (930 years in Genesis 5:5) simplifies slightly the question of how his burial place could have been known to Noah, but Basil provides an important reminder that early Christians were alive to questions of veracity and credible testimony.

Ultimately, the Christian textual tradition surrounding the death and burial of Adam emerges out of a desire to interpret Scripture. In their exegesis, each of these three witnesses—Jerome, Epiphanius, and Basil—read Adam’s death in light of a central Christian claim of redemption in Christ. Jerome emphasizes the typological significance of how Christ’s redemptive death subverts a place of common execution, while Epiphanius graphically illustrates the cleansing of sin in through the blood dripping on Adam’s skull, and Basil completes the image with a meditation on the novelty of death to a humanity who had only recently left Paradise.

Each author stresses God’s providential selection of the “place of the skull” to become the origin of life out of death. These textual witnesses suggest that rather than merely transmitting a static fact, a dynamic Christian tradition situates Adam’s bones under the Cross precisely because of what the Cross is, not for Adam alone, but for “all his descendants” who inherit both his image and his mortality.

Creation of the Space: the Chapel of Adam in Architecture

By the fourth century, the tradition of Adam’s burial offered a compelling answer of the enigmatic Scriptural “place of the skull.” Around the same time, increasing interest in historical sites of Scriptural narrative coupled with Constantine’s inauguration of building campaigns to enshrine those sites in monumental churches resulted in the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (335 CE) over the site of Jesus’ tomb, at a geographically probably and miraculously verified location.

An understandable assumption about the Chapel of Adam might be that it was created along with the whole church complex in the fourth century, bringing the narrative tradition to architectural light along with the Constantinian discovery of the empty tomb. In fact, it was not until the seventh century that the weight of the tradition surrounding Adam’s burial under the Cross became officially instantiated in architecture. Prior to that time, the rock of Golgotha was surrounded by a silver screen, but was not in enclosed within Constantine’s fourth-century church. Even a few centuries later, the Piacenza Pilgrim (570 CE) witnesses to the visibility of at least part of the rock, identifying the red veins in the stone as traces of the “sacred blood of Christ.”[19] These veins are still apparent in pieces of the stone surrounding Golgotha as it stands in the modern Church of the Holy Sepulcher—but the rock itself looks very different than it did when the Piacenza Pilgrim encountered it.

Following the devastation of the Persian invasion in 614 CE, the Holy Sepulcher underwent renovations and repairs directed by Modestus (d. 630 CE).[20] With the Constantinian-era silver screen gone, the rock was enclosed within the “Church of Golgotha,” a narrow space measuring 9–10 meters above the floor of the courtyard and between 3–4 meters in width.[21] Underneath, in the same renovations, the Chapel of Adam was constructed within the rock of Golgotha. Gibson and Taylor note that the cave was cut into a natural flaw or crack in the rock, and suggest that this space was enlarged deliberately as a result of speculation about Adam’s burial place.[22]

In sum, the architectural progression from an Iron Age quarry to a liturgically connected complex relies on Scriptural testimony read through the elaboration of the tradition of Adam’s burial under Golgotha. Devotion and narrative, in other words, prompt architectural instantiation—which itself authenticates of the location of the historical event.[23]

Critiquing the Place: Skeptical Readings of Golgotha and the Chapel of Adam

At this point, the initial question about how the Chapel of Adam emerged seems answered: the architectural creation of the Chapel of Adam relied on a narrative about Adam’s burial, which emerged from Scriptural exegesis about the passion of Christ.

Yet the question of historicity and its implications remains: the site of the Crucifixion was recorded in Scripture, but it took nearly two centuries at least for Christians to be interested in the geographic site itself, as Brouia Bitton-Ashkelony has compellingly shown.[24] Reminiscent of Basil’s concern about the fragility of memory after the Flood, some scholars take a skeptical stance toward the geographical and literary evidence of the traditional identification of Golgotha, suggesting that memory of the exact spot of Crucifixion, burial, and related events was not perfectly preserved.

To take one example, Joan E. Taylor objects to the identification of the Biblical place of crucifixion with the rock identified as Golgotha (Calvary) and venerated today in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. She argues that second-century evidence from Melito of Sardis identifies the place of Jesus’ execution in a different place, nearer to the main roads—a more logical place for public execution than the site traditionally identified as Golgotha from the early fourth century onwards. She concludes that “early literary evidence seems to suggest that biblical Golgotha was indeed closer to Gennath Gate than the traditional site under the Church of the Holy Sepulcher,” and suggests that the notable and elevated “rock of Calvary” was merely a natural geographic feature left over from the quarry due to a flaw in the rock.[25] In another study, Taylor suggests along with Gibson that Christians in the earliest centuries called the entire area of the Crucifixion “Golgotha,” gradually shifting the expansive name more narrowly to the rocky outcropping now identified as Calvary.[26]

The challenge to the site of the Crucifixion that Gibson and Taylor put forth is a valuable one, for it exposes the difference between theological and historical approaches to these sites. The question is whether the Crucifixion actually happened, but where to locate the historical site. Taylor’s reading of the architectural and archeological evidence pits the historical record against the traditional devotional site. In this view, the traditional site of the Crucifixion (the Chapel of Golgotha in the Holy Sepulcher) does not actually provide a concrete historical or geographical link to the event itself.

Though less dramatic than Taylor’s objections to the traditional site of Golgotha, a similar problem arises from what we have seen in the textual and archeological evidence for Adam’s burial under Golgotha. The evidence simply cannot provide conclusive certainty that pre-historic bones would be excavated from the crack under Golgotha. Does this inability to affirm the historical veracity of a sacred site impact the efficacy of the space, or its impact in the lived devotional encounter of Christians pilgrims?

One the one hand, it is a problem: even if the goal of Christian pilgrimage or veneration is not identical to the interest of a historian or tourist (whose only concern is to see a verified historic site), a credible connection between event and place still matters. The fervent engagement of the present-day pilgrims in Church of the Holy Sepulcher testifies that historical and geographical claims are the crucial attraction to these sacred sites. The whole idea of pilgrimage itself relies on a geographical connection to a historic event.

On the other hand, these objections offer a perfect frame to understand that Christian relationship to sacred space seeks far more than remote and absolute historical certainty of past events and places. The unique claim of Christianity means that Christian pilgrimage can and should seek not just the sacred space, but a living encounter with a living God through the sacred space. This is demonstrated nowhere better than the liturgical use of the Chapel of Adam, to which I now turn.

Effective Encounter: the Chapel of Adam in Liturgy

The tradition of Adam’s burial at Golgotha was as early as Origen in the second century, but it was not until the seventh century that we have the first evidence for a specific devotional space commemorating this burial. Our first witness to the liturgical use of a Chapel of Adam encapsulates the Christian understanding of what liturgy effects and renders visible.

Adomnan, the abbot of Iona, records a pilgrimage to Jerusalem by a cleric named Arculf around 680 CE, in a work on the holy places (De Loco Sanctis, written around 704). This text offers the first glimpse of a fully constructed “Chapel of Adam” proper under Golgotha, in the course of narrating various sites within the Church of the Holy Sepulcher:

Towards the east, in the place that is called in Hebrew Golgotha, another very large church has been erected. In the upper regions of this a great round bronze chandelier with lamps is suspended by ropes and underneath it is placed a large cross of silver, erected in the selfsame place where once the wooden cross stood embedded, on which suffered the Saviour of the human race. Now in this church, beneath the place of the Lord’s cross, there is a grotto cut out of the rock where sacrifice is offered on an altar for the souls of certain privileged persons. Meanwhile their remains are laid out in the court before the door of this church of Golgotha, until such time as the holy mysteries for the deceased are completed.[27]

Though not explicitly identified with Adam in Adomnan’s account, this “grotto” stands in the place that Christian writers link with the burial of Adam (as we have seen in Epiphanius and Basil). The focus here, however, is the decoration and liturgical use of the space. In contrast to the lavish upper church, the lower grotto was quite small (2m high and 1.5m wide), explaining perhaps why the deceased lay outside the chapel during the liturgy on their behalf.[28]

The restriction of this prayer to the “certain privileged persons” notwithstanding, the burial place of Adam reaches its fullest instantiation as liturgical site of commemoration and intercession. In one sense, the origins of the space lie in geographic claims about Adam’s burial which are likely more legendary than true. But in a more important sense, the liturgical use of the space expresses the same instinct which motivated the narrative in the first place (as we saw in Jerome, Epiphanius, and Basil): confidence that the Cross brings life out of death for all humanity.

The chapel brings to reality and fruition the underlying convictions of the Christian narrative of Adam’s burial under Golgotha. Questions of place and historicity are not unimportant—the geographical connection to the site of the Crucifixion heightens the efficacious encounter—but the place of the Crucifixion is secondary to the true and efficacious work of the Cross accomplished in the liturgy.

The liturgical use of the space proclaims the renewal of the human race in Christ: the corpse proclaims the mortality inherited from Adam, while the prayers for the dead underneath the site of the Crucifixion proclaim Christ’s life-giving transformation of that mortality. The liturgy effects and makes present the life-giving power of the Cross: the location merely intensifies what all liturgy effects.

The Chapel of Adam, like the monumental construction of the Holy Sepulcher itself around the tomb and Golgotha, arises from a central conviction that Christ has by the Cross redeemed the world and our mortality has become the means of our redemption. Thus, the chapel finds its truest expression in the liturgical use—entrusting the dead to the redemptive mercy of Christ in the very place where his life-giving blood had stained the rocks.

Conclusion: The Chapel of Adam and Christian Devotion

Much remains to be said, but I have at least sketched here the fascinating emergence of the Chapel of Adam and suggested some implications for the study of liturgy, devotion, and sacred space.

To answer my initial curiosity about how the Chapel of Adam came to be under Golgotha, three stages emerge: first, the earliest witness, Origen, demonstrates the theological instinct to decode the meaning of the name “Golgotha” as the “place of the skull,” through the Pauline reading of Christ’s death as redemptive for mankind through Adam. Second, this theological connection seems to prompt the graphic geographical connection between Adam’s corpse and the site of the Crucifixion, as seen in Epiphanius and Jerome. Finally, the seventh century saw an architectural instantiation of the legend in the Chapel of Adam in the Holy Sepulcher.

Ultimately, the origin of the Chapel of Adam in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher seems to be fundamentally the creation of space prompted by devotion or legend. An overly skeptical or historical lens could dismiss the space as a fanciful devotion, created by theology rather than recorded in history. But the question of a pilgrim is not the question of a historian, however valuable and useful that might be.

For the Christian pilgrim, a sacred space subverts the question of strict veracity. For the pilgrim, a core historical event must be affirmed—the Crucifixion and Resurrection really happened. But Christian faith and identity do not depend on strict certainty about the geography of the historical sites of the life of Jesus of Nazareth; the claim of Christian faith involves more than a geographic memorialization. The centerpiece of the Holy Sepulcher is, after all, an empty tomb. The attraction of pilgrimage is an increase in devotion and facilitation of an encounter with God; the danger of pilgrimage is being subsumed in fascination or concern with merely historical reality. Instead, all pilgrimage to sacred sites is intended to form and facilitate worship and growth in Christian identity.

The Chapel of Adam demonstrates the tension between these two poles of sacred space: the connection to history and the orientation to eternity. And, indeed, the sparse textual and architectural record, as well as its lack of decoration, serves to intensify its utility for the discussion. Unlike the other sites in the Holy Sepulcher (even today!) the Chapel of Adam is not sought or venerated on its own terms; it defies in its very unadorned walls and lack of identification the voyeuristic instinct of pilgrimage as tourism to a merely historical site.

I began with Mark Twain’s half-satirical instinct to reflect on Adam as a “distant relation” because it hints at the deeper truth communicated through the narrative and architecture of the Chapel of Adam. As witnessed in Jerome, Epiphanius, and Basil, the tradition of Adam’s burial on Golgotha grows from the central conviction of the redemptive and vivifying power of the Crucifixion. Ultimately, the question of strict historical convergence of site and event is secondary in Christian life to the fact of redemption accomplished by Christ and encountered in the liturgy: for as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.

[1] Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad (New York: Harper and Bros., 1911), chapter 53.

[2] For a discussion of evidence attributed to Origen’s contemporary Julianus Africanus (ca. 180–250 CE) which witnesses to Adam’s burial in Jerusalem and also refers to a “Hebrew” tradition, see Jordan Ryan, From the Passion to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Place, 2021), 29.

[3] Origen, ‘Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew,’ §126 (c. 212– 216 CE). For a recent English translation, see Ronald E. Heine. The Commentary of Origen on the Gospel of St Matthew. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. Vol. 2, 740.

[4] See Ryan, From the Passion, 26.

[5] Ryan, From the Passion, 48.

[6] Gary Anderson, The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001).

[7] For a discussion of the Jewish sources attesting the burial of Adam and Eve, see Jordan Ryan, “Golgotha and the Burial of Adam Between Jewish and Christian Tradition,” Nordisk Judaistik 32 (2021): 7–8.

[8] Greek Life of Adam and Eve 38.4. For critical edition see Johannes Tromp, The Life of Adam and Eve in Greek. Vol. 6 (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

[9] For the creation of Adam outside Eden, see Jubilees 3:9 (“After 40 days had come to an end for Adam in the land where he had been created, we brought him into the Garden of Eden to work and keep it.”) For the burial of Adam, see Jubilees 4:29 (“At the end of the nineteenth jubilee, during the seventh week—in its sixth year [930]—Adam died. All his children buried him in the land where he had been created. He was the first to be buried in the ground.”) Translation and commentary in James C. VanderKam, and Sidnie White Crawford. Jubilees (Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2018), 206, 236.

[10] Jubilees 4:29. Cf GLAE 40:4–5. See commentary in VanderKam and Crawford, Jubilees, 265.

[11] Jerome, Commentary on Ephesians, trans. in Ronald E. Heine, The Commentaries of Origen and Jerome on St. Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 648–650. See also Comm. in Matt. 27:23 (SC 259:280–290). On the dating of the letter in relation to Jerome’s other writings, see Pierre Nautin, “La Lettre de Paule et Eustochium à Marcelle (Jérôme, Ep. 46),” Augustinianum 24, no. 3 (1984): 441–49.

[12] Ep. 46.3, in Nautin, “La lettre de Paule,” 445.

[13] Bruria Bitton-Ashkelony, Encountering the Sacred: the Debate on Christian Pilgrimage in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), chapter 2, esp. 73–85.

[14] Thomas O. Schenk, St. Jerome: Commentary on Matthew: The Fathers of the Church Patristic Series (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2008), 315–16.

[15] Pan. 46.5.1–9, trans. by Frank Williams, The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Book i (Sects 1–46), Nag Hammadi and Manichean Studies 63, Second Edition (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 379.

[16] Epiphanius here attends to both blood and water described in John 19:34, while most other witnesses to the Adam/Golgotha conjunction in text and later in iconography focus on the blood alone. For a survey of views on the blood and water flowing from the side of Christ, see Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John: Volume 2 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966), 946–52.

[17] Comm. Is. 5.141 (PG 30.478), trans. by Nikolai A. Lipatov, St. Basil the Great: Commentary on the Prophet Isaiah, Texts and Studies in the History of Theology 7 (Mandelbachtal: Edition Cicero, 2001), 162.

[18] Sergey Minov, “Translatio Corporis Adæ,” in Igor Dorfmann-Lazarev (ed.), Apocryphal and Esoteric Sources in the Development of Christianity and Judaism, (Leiden: Brill, 2021).

[19] Piacenza Pilgrim, Itin.,19. In John Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims Before the Crusades. Second edition. Warminster: Aris & Philips, 2015, 220. Gibson and Taylor suggest that “the mizzi hilu stone is white with red veins, and it is probably these veins which are referred to by later Christian pilgrims as traces of Christ's blood.” Shimon Gibson and Joan E. Taylor. Beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem: The Archaeology and Early History of Traditional Golgotha (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1994). 11.

[20] Justin, Kelly, The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Text and Archaeology (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2019), 110.

[21] Gibson and Taylor, Beneath the Church, 83; Kelly, Church, 110–111.

[22] This structure was destroyed in 1009. Gibson and Taylor Beneath the Church, 83.

[23] See the conclusion that it was only in the seventh century that the “tradition of Adam’s burial was given ‘official’ architectural codification.” The relation between “official” and “popular” narrative or tradition remains an interesting strand to develop in further research into architectural sites. Ryan, “Golgotha,” 21.

[24] Bitton-Ashkelony, Encountering the Sacred, 19–29.

[25] Gibson and Taylor, Beneath the Church, 60, citing Joan E. Taylor, Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish–Christian Origins (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1993), 113–122, 134–136.

[26] Gibson and Taylor, Beneath the Church, 60, citing Cyril (bishop of Jerusalem) who uses of “Golgotha” to refer to the entire area (Cat. 1:1; 4:10, 14: 5:11; 10:19; 12:39; 13:4, 2, 28, 39; 16:4) and the pilgrim Egeria’s similar use of the term (Itin. 25:1–6, 8–10; 27:3; 30:1; 37:1; 41:1).

[27] De Loc. Sanct. 1:5.2, translation as in Denis Meehan (ed.), Adamnan’s De Locis Sanctis (Dublin: Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies, 1958), 48. Cf translation in Wilkinson Jerusalem Pilgrims, 173.

[28] Cited in Gibson and Taylor, Beneath the Church, 83.