The Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross on September 14th is nestled into the many-month expanse of liturgical “ordinary time.” In this calendrical “green space,” the memory of Eastertide sustains us as we live into Christ’s resurrection daily and anticipate his Incarnation; as we stand between the poles of Eastertide and Advent in the liturgical calendar, we exalt the Cross. But why? In April, we observed the Cross’s crowning achievement—the Paschal Mystery. What more does the Cross hold for us and why does it beg “exaltation”?

A 21st century, Western perspective on the cross, or any religious symbol, tends to fall into theological abstractions. However, the origins of the Exaltation reveal a feast rooted in liturgical devotion—a movement from lex orandi to lex credendi. Furthermore, at the center of this liturgical feast is an actual object, an image that has excited devotion since its first appearance in late antiquity. The theological implications of this liturgical devotion reveal not simply another occasion to commemorate Good Friday, but an opportunity to acknowledge the potency of the Cross itself and its polyvalent meaning.

History of the Feast

The feast has its origins in 4th century Jerusalem, where a relic of the True Cross was lifted up (“exaltio”) during the eight-day commemoration of the dedication of the Church at Golgotha and the Church of the Resurrection (the Anastasis). The Old Armenian Lectionary records that on the second day of the dedication (September 14th): “the venerable, life giving [and] holy Cross was displayed for the whole congregation.”[1] This simple liturgical act lies at the heart of the Exaltation. Even before it becomes the independent feast we know today, early Christians were compelled to venerate the Cross and from this act, the feast day grew.

The 4th century pilgrim, Egeria, may have participated in one of the earliest forms of this commemoration; she connects the Cross with the Church Dedications because the “the Cross of the Lord was found on this same day.”[2] While there are some variations on how the relic of the True Cross was found, a tradition of St. Helena founding the Cross takes hold in early Christianity. In his 4th c. History of the Church, Rufinus recounts one of the earliest versions of the story:

It was at this time that Helena, Constantine’s mother, a woman matchless in faith, devotion, and singular generosity . . . was alerted by divine visions and traveled to Jerusalem, where she asked the inhabitants where the place was where the sacred body of Christ had hung fastened to the gibbet . . . when, as we said, the pious woman had hastened to the place indicated to her by a sign from heaven, and had pulled away everything profane and defiled, she found deep down, when the rubble had been cleared away, three crosses jumbled together.[3]

The founding of the Cross was essential to the emergence of the Exaltation. For one, it is unlikely the practice of exalting a Cross would have taken hold in Jerusalem without a Cross to lift. In her book, The Cross, Robin Jensen suggests that the founding of the True Cross contributes to the gradual integration of the Cross in early Christian art.[4] Prior to the 4th century, representations of the Cross are uncommon in Christian iconography despite its recurring literary significance in the New Testament and other early Christian writings; but Jensen observes: “Shortly after its discovery in the fourth century, the True Cross became an object of veneration for its own sake.”[5] The practice of exalting the Cross on September 14th proves that the Cross did, in fact, emerge as “an object of veneration for its own sake.” And as Jensen suggests, it is very likely these kinds of liturgical practices, made possible by the Cross’s founding, contributed to the Cross’s emergence as the Christian symbol.

Cross as Relic

Rufinus’s account highlights an aspect of the Cross, which will become essential to its meaning in the Exaltation and other feasts: its potency as the relic par excellence. Not knowing which of the three crosses was the Cross of Christ, Helena takes them to Bishop Macarius of Jerusalem, who then takes the three crosses to a woman on her death bed:

The first touched her with one of the three, but it did not help. He touched her with the second, and again nothing happened. But when he touched her with the third, she at once opened her eyes, got up, and with renewed strength and far more liveliness than when she had been healthy before, began to run about the whole house and glorify the Lord’s power. The queen then, having been granted her prayer with such a clear token, poured her royal ambition into the construction of a wonderful temple on the site where she had found the cross . . . part she put in silver reliquaries and left in the place; it is still kept there as a memorial with unflagging devotion.[6]

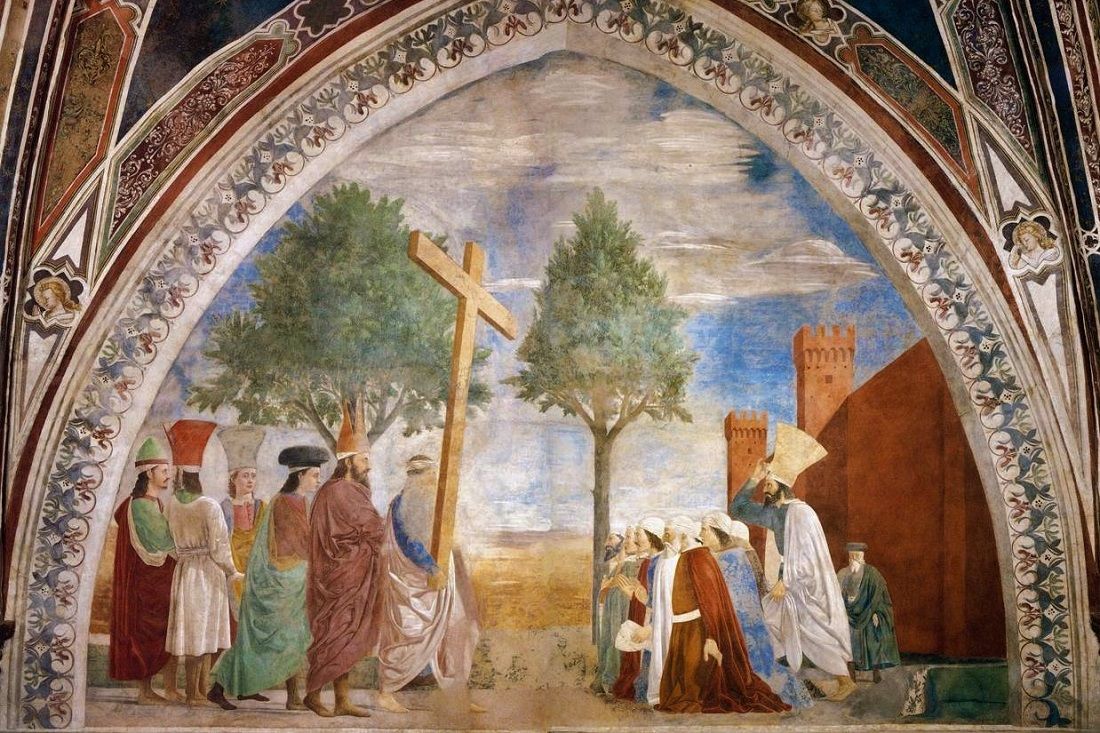

The miraculous power of the Cross was its measure of legitimacy. Indeed, stories detailing the power of the Cross relic becoming commonplace as fragments of the True Cross make their way around the Christian world. As the relics of the True Cross spread, so too did the Exaltation. The spread of relics and the feast outside of Jerusalem made way for the Exaltation’s gradual separation from the dedication commemorations at Jerusalem. The first record of an independent Exaltation of the Cross Feast in the West appears in the Old Gelasian Sacramentary from the 7th century. While various factors played into the Exaltation’s growth into an independent feast, the story of Emperor Heraclius’s recovering the Jerusalem Cross in 630 C.E. plays no small role. According to tradition the Persians seized the Jerusalem Cross in 614 C.E., which prompted a military attack by Heraclius. In the process, he recovered the Cross from the Persians and restored it to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Hagiographical accounts understand his restoration as a kind of refounding of the Cross that mirrors that of St. Helena a few hundred years before. The triumphant “rediscovery” seemed to excite devotion of the Cross in subsequent centuries and likely contributed to the growing popularity of the Exaltation of the Cross.

Symbolism of the Cross

Eventually, Jerusalem’s relic of the True Cross disappears, but the devotion surrounding the paradigmatic Christian symbol remains. The Cross’s potency in the Exaltation Feast and beyond was not restricted to “true” relics:

In practice, any likeness of the cross, however ordinary or grand, could contain and convey the spiritual power of the original object . . . the image itself became a relic, a transformation that grew even more important in the centuries after the original relic had been captured and desecrated by its enemies.[7]

Veneration of the relic’s fragments and of the Cross as a potent symbol of the Christian faith endures and, with it, the feast commemorating this sacred object and symbol. The Church worldwide exalts the Cross on September 14th whether it possesses a Cross relic or not.

But what meaning lies behind this symbol with “spiritual power”? In the Exaltation Feast and beyond, the Cross signifies more than the dramas around St. Helena and Heraclius. At its core, the Cross stands in as a metonymy of the Paschal mystery: once a means of humiliating capital punishment, Good Friday recasts the Cross and awards it a role in the drama of salvation. The Jerusalem calendar also venerated the True Cross on Good Friday; Egeria records that the faithful, one-by-one, would come up and kiss the relic of the True Cross in the midst of liturgies mourning the death of Christ. The veneration during the Exaltation feast seems different than the veneration performed on Good Friday. While the Good Friday veneration punctuates the significance of the Cross as a symbol of Christ’s Passion, the Exaltation punctuates an empty, triumphant Cross. The Holy Wood testified to a crucified Lord, but the fact remained that the he no longer remained on it. This is the fundamental paradox of the Cross, the reason that an instrument of death could be lifted up in an act of triumph during the Exaltation.

In St. Ambrose’s account of St. Helena finding the True Cross, her search is spurred on by her zeal for the Cross as a symbol of triumph:

She drew near to Golgotha and said: “Behold the place of combat: where is thy victory? I seek the banner of salvation and I do not find it. Shall I,” she said, “be among kings, and the cross of the Lord lie in the dust? Shall I be covered by golden ornaments, and the triumph of Christ by ruins? Is this still hidden, and is the palm of eternal life hidden? How can I believe that I have been redeemed if the redemption itself is not seen? I see what you did, Devil, that the sword by which you were destroyed might be obstructed . . . let the sword by which the head of the real Goliath was cut off be drawn forth; let the earth be opened that salvation may shine out. Why did you labor to hide the wood, Devil, except to be vanquished a second time? . . . I shall search for His cross. [Mary] gave proof that He was born; I shall give proof that He rose from the dead. She caused God to be seen among men; I shall raise from ruins the divine banner which shall be a remedy for our sins.”[8]

The speech of Helena crafted by St. Ambrose does not identify the Cross as a symbol of Christ’s suffering or death. Instead, she casts it as “the triumph of Christ,” “redemption itself,” “the sword by which [the Devil was] destroyed,” and “the palm of eternal life.” She specifies that in finding the Cross, she will not prove that he died, but rather that “he rose from the dead.” In this, the Cross appears as a sign of Resurrection more than it does a sign of death. The focus is not on the wounds of Christ, but the wounds Christ inflicted on Satan in his defeat of death.

Ambrose’s oration also highlights the early Christian tendency to see images of the Cross throughout the Hebrew Bible. In Helena’s speech, Christ wielded the Cross as a sword to defeat the Devil in a manner that mirrors David’s beheading of Goliath with a sword.

Early patristic exegetes made frequent use of vignettes in Israelite history as typologies of Christ’s salvation on the Cross. In his Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, John of Damascus sweeps through Israelite history and identifies foretastes of the Cross:

The tree of life which was planted by God in Paradise pre-figured this precious Cross. For since death was by a tree, it was fitting that life and resurrection should be bestowed by a tree. Jacob, when He worshipped the top of Joseph’s staff, was the first to image the Cross, and when he blessed his sons with crossed hands he made most clearly the sign of the cross. Likewise also did Moses’ rod, when it smote the sea in the figure of the cross and saved Israel, while it overwhelmed Pharaoh in the depths; likewise also the hands stretched out crosswise and routing Amalek; and the bitter water made sweet by a tree, and the rock rent and pouring forth streams of water and the rod that meant for Aaron the dignity of the high priesthood: and the serpent lifted in triumph on a tree as though it were dead, the tree bringing salvation to those who in faith saw their enemy dead, just as Christ was nailed to the tree in the flesh of sin which yet knew no sin.[9]

In these typologies, John of Damascus associates the saving work of wood in the Hebrew Bible to the saving work of the Cross. The Cross is exalted as a new Tree of Life—a promise of restored paradise, paternal blessing, and salvation from oppression and danger. The lectionary continues in this tradition, for the Exaltation Feast includes Numbers 21:4 –9 and a passage from the Gospel of John that typologically interprets it:

No one has ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life (Jn. 3:13 –15).

In the same way the Israelites were saved from death by the lifting up of the bronze serpent on a wooden pole, so too is the world saved by the lifting up of Christ on the Cross.

In early Christianity, the Cross indicated Christ’s eschatological triumph with as much force as it indicated his initial triumph over death in the Resurrection. Some early exegetes understood that the “Sign of the Son of Man” Christ promised in Matthew 24:30 would be an image of the Cross. (e.g. John Chrysostom, Homily 76 on Matthew). A feast celebrated by the Orthodox Church on May 7th commemorates the appearance of a Cross of light in the sky over Jerusalem in 351 C.E. Bishop Cyril of Jerusalem interpreted this staurophany as a fulfillment of the Sign promised by Christ in his apocalyptic message in Matthew 24; the gospel reading for subsequent liturgical commemorations of this event employed Matthew 24 and incorporated lectionary readings that framed the Cross as this eschatological sign.[10]

In the West, there is not a feast that commemorates the eschatological nature of the Cross (exclusively); but the eschatological promise of Christ’s return is embedded into the narrative of Christ’s death on the cross and his Resurrection. Early Western iconography acknowledges the eschatological force of the Cross. The 5th–6th c. apse mosaics in the basilica of Sant’Apollinare and Santa Pudenzia both display images of a jeweled, empty cross looming above scenes that evoke the eschatological future Christ promises.

The Exaltation of the Cross Feast also encourages an understanding of the Cross that transcends crucifixion. Jensen illustrates that Cross imagery did not focus on the suffering Christ until the middle ages: “Before the tenth or eleventh century, both Eastern and Western depictions typically refrained from showing Jesus as suffering physical agony and death.”[11] A theological and iconographic shift begins to occur in the 10th–11th century; but interestingly enough, the Exaltation of the Cross Feast does not follow suit. In his study of the Exaltation of the Cross Feast in the West, Lois von Tongeren notes that the image of pain and suffering does not make its way into the liturgical texts for the Exaltation.[12] Even in the lectionary for the Feast mention of Christ’s death on the Cross is always to the end of his exaltation:

who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.Therefore God also highly exalted him

and gave him the name

that is above every name,

so that at the name of Jesus

every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father (Phil. 2:6 –11).

Quite simply, the message of the Exaltation Feast is just that—a message of Christ exalted. While the Cross is given fame in the Passion, it is transformed into an image of victory. But the Exaltation of the Cross Feast does not offer a single, easily digested nugget of truth. Instead, it melds soteriology, typology, and eschatology. The Cross evokes Christ on the Cross, but also Christ in Glory. It recalls the Israelites in the wilderness and yet also the liturgical life of 4th century Jerusalem. It simultaneously evokes the life of Christ and the life of the saints. It points us to moments in time and yet remains completely apart from time. This is, in fact, is what liturgical time is all about. The Exaltation of the Cross feast teaches us what every liturgical feast and season should—that daily we remember a faith that is both before and after us, within time and without time.

And yet even in this more general lesson, the Exaltation of the Cross maintains specificity. The Cross is a particular object that came from a particular place and time; while it transcends time, the role it had in the Paschal mystery granted it power. It emerged as a symbol that not indicates Christ’s suffering and death, but also his triumph and glory; the Exaltation gives us an opportunity to acknowledge and adore it. As members of the Body of Christ, the Cross comes to symbolize our own suffering and triumph as well. We are lifted up on the Cross in Christ’s crucifixion but we also wield the empty Cross, which promises new life and eschatological fulfillment.

[1] Armenian Lectionary 67-68 in Louis von Tongeren, The Exaltation of the Cross: Toward the Origins of the Feast of the Cross and the Meaning of the Cross in Early Medieval Liturgy, (Sterling, VA: Peeters, 2000),17.

[2] Egeria, Itinerarium, 48.2.

[3] Rufinus of Aquileia, History of the Church, 10.7 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University, 2016), 391.

[4] Robin Margaret Jensen, The Cross : History, Art, and Controversy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 2017), 120.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 10.8.

[7] Jensen,122

[8] Ambrose of Milan, “Funeral Oration for the Death of Theodosius,” 43-44 in Funeral Orations (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University, 2004), 326-7.

[9] John of Damascus, Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, 4.11 in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers—Second Series, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994), volume 9, part 2, 80–81

[10] Cyril of Jersualem, Letter to Constantius II in Cyril of Jerusalem and Nemesius of Emesa, Library of Christian Classics, ed. Willian Telfer, (Philadelphia, PA; London: SCM Press, 1955).

[11] Jensen, 151.

[12] von Tongeren, 284.