How you are fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! How you are cut down to the ground, You who weakened the nations! For you have said in your heart: “I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God; I will also sit on the mount of the congregation. On the farthest sides of the north; I will ascend above the heights of the clouds, I will be like the Most High.” Yet you shall be brought down to Sheol, To the lowest depths of the Pit. “Those who see you will gaze at you, And consider you, saying: ‘Is this the man who made the earth tremble, Who shook kingdoms, Who made the world as a wilderness, And destroyed its cities, Who did not open the house of his prisoners?’” (Isa 14:12-17).

Angelic Vision

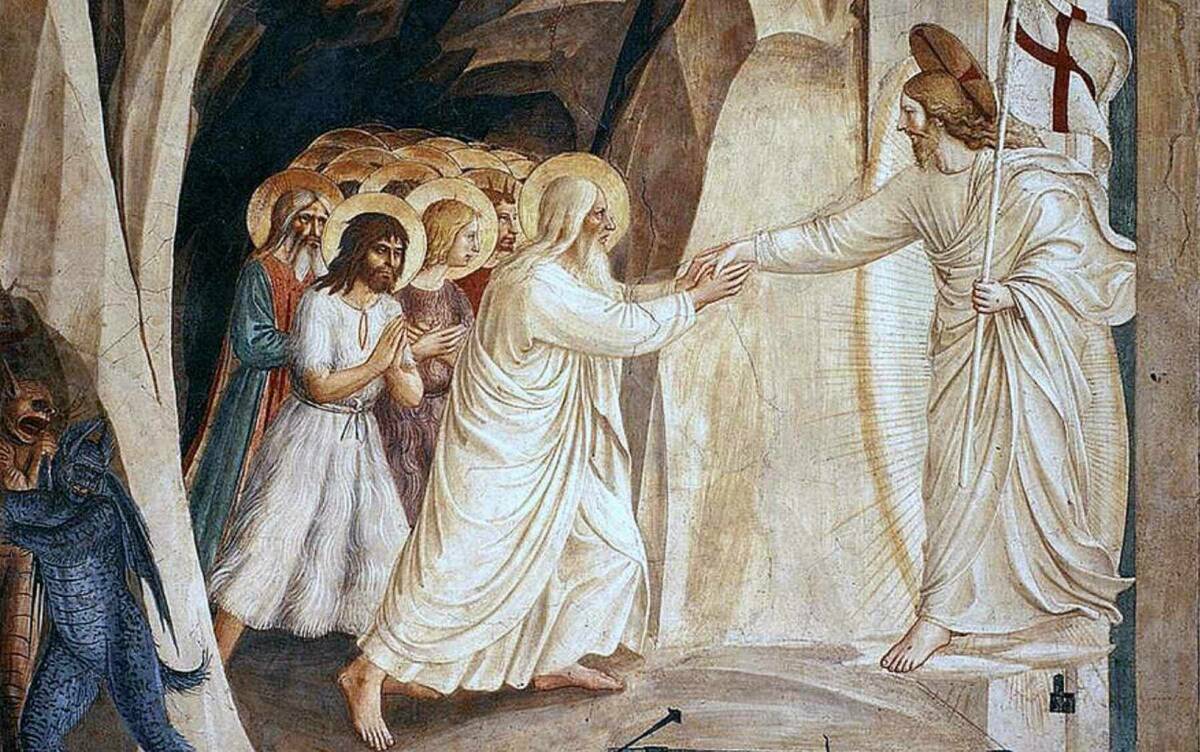

Lucifer sought to grasp the city of God and created wilderness, to attain the heights of the Most High and yet fell to the pit. Lucifer’s ultimate defeat, however, rests in the altogether different “fall” of Christ who gave himself over to death on the cross and descended into the grave, for in that fall he reverses sinful motion and extends his authority to the pit itself. Just as sin grasps upwards in self-interest, so Christ’s salvific gesture reaches down in self-denial. Capturing this reality, Fra Angelico, in his fresco The Harrowing of Hell (Figure 1), portrays Christ reversing the power of Lucifer in an ultimate gesture of victory.

He enters the wilderness, destroys Lucifer’s city, and opens the gates to free the prisoners. In this work, Christ does not only reach into the pit of hell to draw man to salvation but also accomplishes a greater victory. He enters into the wilderness of Lucifer and transforms it into the realm of his kingdom.[1] Therefore, the wilderness entered through descent into sin has become a place from which to ascend again to God. Christ has brought the light of God, through his presence providing a foretaste of the final, permanent light of the city of God.[2]

Within Fra Angelico’s depiction, he highlights the arrival of Christ into a lifeless wilderness through the barrenness of the cavity from which the prisoners arise—a monochrome, rocky, and barren cave. This desert land seems appropriate for contextualizing the Old Testament figures awaiting God’s promised kingdom from the depths of hell. In the Exodus account, the Hebrew word for “wilderness” or “bamidmar” itself derives from the desert in which the Jews wandered for 40 years in Exodus.[3]

And yet that wilderness always bore with it the hope of God’s presence, God’s covenantal promise for future glory in the promised land. As Paley observes, the desert of “bamidbar” also suggests the presence of the “word” or “devar.”[4] And so, figuratively, the wilderness becomes a place to encounter the word. Throughout the Old Testament, God’s word of the covenant had transformed the wilderness with hope of a future city, and now, in The Harrowing of Hell, the very Word of God fulfills that hope by entering into hell and establishing the City of God out of the wilderness of humanity’s fall.

We will examine the Old Testament figures of the fresco who lead the crowd toward Christ, though their histories, tracing God’s continual redemptive plan for the wilderness. Reflecting on these stories and their culmination in Christ’s entry through the gates of hell gives us a sense of past and present time conjoined, allowing us to simultaneously enter the wilderness and participate in Christ’s Kingdom, descend into hell while ascending to heaven. Finally, we will look at the fresco’s location within a Dominican cell in the monastery San Marco of Florence as a way to capture the power of the world of prayer and preaching to bring heaven into the wilderness of this world.

Adam, the First

Fra Angelico’s depiction in The Harrowing of Hell includes five recognizable figures leading a crowd processing from the darkness of the cave to join Christ. Adam is at the head, grasping Christ’s hands, followed by John the Baptist, Abel with bloodied head, Moses with horns of light, and David with a gold crown adorning his head.[5] Though these figures are consistently present throughout images of the Harrowing of Hell, the Italian tradition diverged from previous Byzantine images through its asymmetrical composition, with the prisoners emerging from one side towards Christ, as opposed to gathering around him.[6]

As a result, Adam is emphasized as the first man, the first to fall to the grave, and now the first to be saved. Fra Angelico further emphasizes his centrality by placing him directly in the center of the painting, larger than the figures behind him. Furthermore, he grasps Christ’s hands, directly engages Christ’s gaze, and is clothed in white robes mirroring those worn by his savior. Worthen argues that, in evoking the Old Adam-New Adam relation of Christ and Adam, Fra Angelico is distinct in portraying their union, with Christ redeeming rather than replacing Adam.[7]

However, in emphasizing Adam’s role as the first to be redeemed by Christ, Fra Angelico does not ignore his original Fall. Adam’s gesture rushing forward and reaching upwards is reflected in the blue demon, flying into the darkness of the bottom left corner, reminding us of Adam’s potential for reverse motion into the dust. Just as Lucifer had grasped for the authority of God, in the Genesis account, Adam had sought to become like God and was banished to the desert. Though imbued with God’s very own image, Adam cast aside God’s authority in favor of his own, losing his very source of life and being, returning the image of man merely to dust.[8] And so, to capture the heart of the salvation narrative, Fra Angelico, in depicting the Harrowing of Hell within San Marco, Florence, begins in that dust. In fact, he begins at the lowest point of Lucifer’s and likewise man’s fall—hell itself.

Christ’s humiliation in taking on the dust of man becomes his glory. In taking on man’s form, he is able to offer it back in triumph, creating a new Adam in the weakness of flesh: “He takes our ‘flesh,’ together with all its limiting factors and inherent flaws, and through a work of supremely ‘inspired’ (Spirit-filled) artistry, transfigures it, before handing it back to us in the glorious state which its original maker always intended it to bear.”[9]

That glorious state, ultimately allows man the freedom to grasp hold of God, no longer in denial of his identity as a creature, but in pursuit of that identity. For Christ hands back to man the dust he had sought to deny, glorified anew through God’s presence. In Fra Angelico’s fresco, Christ holds Adam’s wrist in the traditional gesture of salvation.[10] Man had presumed to grasp the Most High, and now the Most High extends his grasp to the lowest realms, allowing them to grasp hold of him out of their very weakness.

In Genesis, after eating of the forbidden fruit, Adam, aware of his nakedness, sought to hide his shame and ran from God’s voice. And God, in response, sends him from the realm of his presence within the garden into the wilderness, punishing Adam with the downward gesture and movement towards dust he himself had chosen. Within The Harrowing of Hell, not only does Christ reverse that gesture, but Adam is seen embodying the new movement of salvation. Fra Angelico’s depiction of Adam is unique in creating an active figure, running to Christ and taking hold of Christ’s hands himself. For the first time in the iconography of Christ’s descent, Worthen describes, “Adam’s hands are as active as Christ’s.”[11] His body of dust has been reformed, no longer tied to the ground, but actively participating in his ascent.

Furthermore, though still joined to the dust while rising from it, Adam and Christ are ideal and shining, crowned in haloes, with elegant gestures, flowing robes, and radiant faces, lightly floating over the surface of the ground below. Fra Angelico followed the Christian artistic tradition in emphasizing the human nature of Christ, placing him on the same scale as the other figures, including his wounds, and including a sense of bodily presence below his flowing robes. However, he rejects the new tradition of depicting Christ as wasted by that human form. At the time, often while entering hell, “[Christ] is haggard, he wears a shroud, his back is to us, or His is embraced by the just.”[12]

Instead, Fra Angelico, though showing Christ’s entry into the dust of man, simultaneously demonstrates his transformative power through his idealized form. Dust is no longer haggard or worn, but glorious. The transformed wilderness has become an image of the promised city of God because the ground itself has been granted the transformative power of God. Fra Angelico asks us not to run from the physical reality but rejoice in God’s ability to transform it.

Raising Abel

The role of dust in the re-creation of man is enhanced by and reflected in the nature of art itself. Imitating the creative act of God, the artist creates form out of the formless dust of the walls, bringing them to life and imbuing them with meaning. Art reminds us that participation in the glory of God, in his new creation, brings us beyond the dust of life, but never leaves it behind. Jeremy Begbie highlights this point in his comparison of beauty permeating music to the incarnation of Christ:

That God has graciously placed himself in our midst for touching, hearing and seeing means that this same “physical” and historical manifestation must always be the place where we put ourselves in our repeated efforts to know him again and ever more fully. We cannot appreciate Mozart’s artistry unless the sound of his music remains our constant companion; we may appreciate more than the sounds themselves, but never less. There is something more than the “flesh” to be considered, but the two levels must be held together inseparably if the essential significance of each is not to slip from our grasp.[13]

Within The Harrowing of Hell, Fra Angelico particularly emphasizes the relation of the creative power of God to that of art, using the same coloration found throughout the monastic cell walls as foundation for his work, creating the cave of hell using the very material around him. And so now, entering into the dusty cavern of the cell, we too can encounter the image of Christ. The dust originally used to form Adam may become a barren wilderness or the prison of hell itself devoid of Christ’s presence, but through the creative power of the Word of God, that dust can become a symbol of hope for all creation.

Placing Abel behind the figure of Adam adds further richness to Christ’s transformation of the dust of the wilderness. Specifically, Abel demonstrates the power of God to hear man, even when he has been engulfed in the silence of the ground in death. Though Adam was cut off from communion with God in the garden, the Lord remains present with mankind, specifically inclining his ear to the sacrifices of Abel. When Cain, jealous of his brother, seeks to, in essence, sever him from life in God, this first death fails to cut man off from God’s redeeming glance: “The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to me from the ground. And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand” (Gen 4:10-11).

Abel, as the first man to enter the grave, to become cut off through death itself, remained able to call out to the Lord. For the love of God inclines its ear to the very plea of the dead. And so, “death strengthens the consciousness of such a love,”[14] and rather than becoming cut off from God, Abel’s blood, which crowns his head in Fra Angelico’s work, becomes a symbol of God’s care. Entering into the mouth of the ground, Abel points towards God’s loving faithfulness, not only in following man out of the garden, but even when swallowed back into the dust of the ground. Abel’s cry of suffering demonstrates not only man’s longing for communion, but God’s faithfulness to provide that communion. Describing the transformative power of Christ’s descent into the grave, Pope Benedict XVI writes, “Suffering without ceasing to be suffering—becomes, despite everything, a hymn of praise.”[15]

Abel had continually offered sacrifices in praise of the Lord, and so his very own life, when sacrificed, preserves that communion of love. Likewise, within the monastery, even in the simple action of casting himself into the solitude of the monastery cell, the monk can be confident in becoming heard and loved. This small tomb becomes a place of adoration and communion.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This is part one of two in a series reflecting on Fra Angelico’s fresco, The Harrowing of Hell in San Marco, Florence. The second may be found here.

[1] “When it says, “He ascended,” what does it mean but that he had also descended into the lower parts of the earth? He who descended is the same one who ascended far above all the heavens, so that he might fill all things” (Eph 4:9-10).

[2] Revelation 21 presents an image of the final city of God corresponding with Christ’s transformative power in Hell, bringing light and breaking down the gates. See: Rev 21:23 and Rev 21:25.

[3] Paley, “Torah Study; Wilderness of Words Offers Our Best Hope”

[4] Ibid.

[5] Worthen, The Harrowing of Hell in the Art of the Italian Renaissance, 125.

[6] Ibid., 46.

[7] Ibid., 125.

[8] “Till you return to the ground, For out of it you were taken; For dust you are, And to dust you shall return” (Gen 3:19).

[9] Begbie, Beholding the Glory: Incarnation through the Arts, 20.

[10] Worthen, The Harrowing of Hell in the Art of the Italian Renaissance, 43.

[11] Ibid, 126

[12] Ibid, 119

[13] Begbie, Beholding the Glory: Incarnation through the Arts, 25.

[14] International Theological Commission. “Some Current Questions in Eschatology”, 8.2.

[15] Pope Benedict XVI. Saved in Hope: Spe Salvi, 80.