I have heard the phrase “Christians are being persecuted” in the context of American politics enough times in the last few years to know that it has become a piece of folk wisdom. I have seen the tendency to view persecution as confirmation in political discourse in America, particularly in the context of what pundits refer to as “the culture war.” One risk within a democratic society is to think that a majority consensus proves the truth of a statement, that a sheer number of people believing something somehow confirms its truth. Wesley Walker recently drew attention to poll data showing that a majority of American Christians believe they are persecuted, and he wisely counsels against the development of victimhood complexes. It appears that the fact of persecution has reached this level of unquestionability amongst Christians.

Personally, I do not find the claims that American Christians are persecuted to be particularly compelling, unpopular as some beliefs might be in the mainstream, and initially, I thought people’s minds might be changed if they were made aware that persecution cannot prove Christian belief. Using persecution as proof of one’s Christianity is an example of the logical fallacy known as “affirming the consequent,” something I learned about in my brief time in seminary, of all places. The train of thought could be represented this way.

If P, then Q.

If I am a true follower of Christ, then I will be persecuted.

Q.

I am persecuted.

Therefore, P.

Therefore, I am a follower of Christ.

On further reflection, I was reminded that pointing out the illogic of my positions has only ever aggravated me, so “owning” someone with logic likely could have the opposite effect of my intention. Identifying a grievance is often one of the first steps in rallying people to a political cause, and I do not want to downplay Christian persecution’s galvanizing rhetoric in that arena, but it is also obvious to me that persecution does psychological work for Christians—the way that all “complexes” provide justifications for those afflicted by them—and a kind of spiritual work as well.

The truth is, Christians become more confident that they are Christians when they feel persecuted. I want to spend a moment exploring how a misunderstanding of certain Gospel passages can lure people into this way of thinking, and then I hope to show how attending to the logic of the gospel’s promise better prepares us to accept the burden of discernment and the calling to hope.

The Logic of Scripture

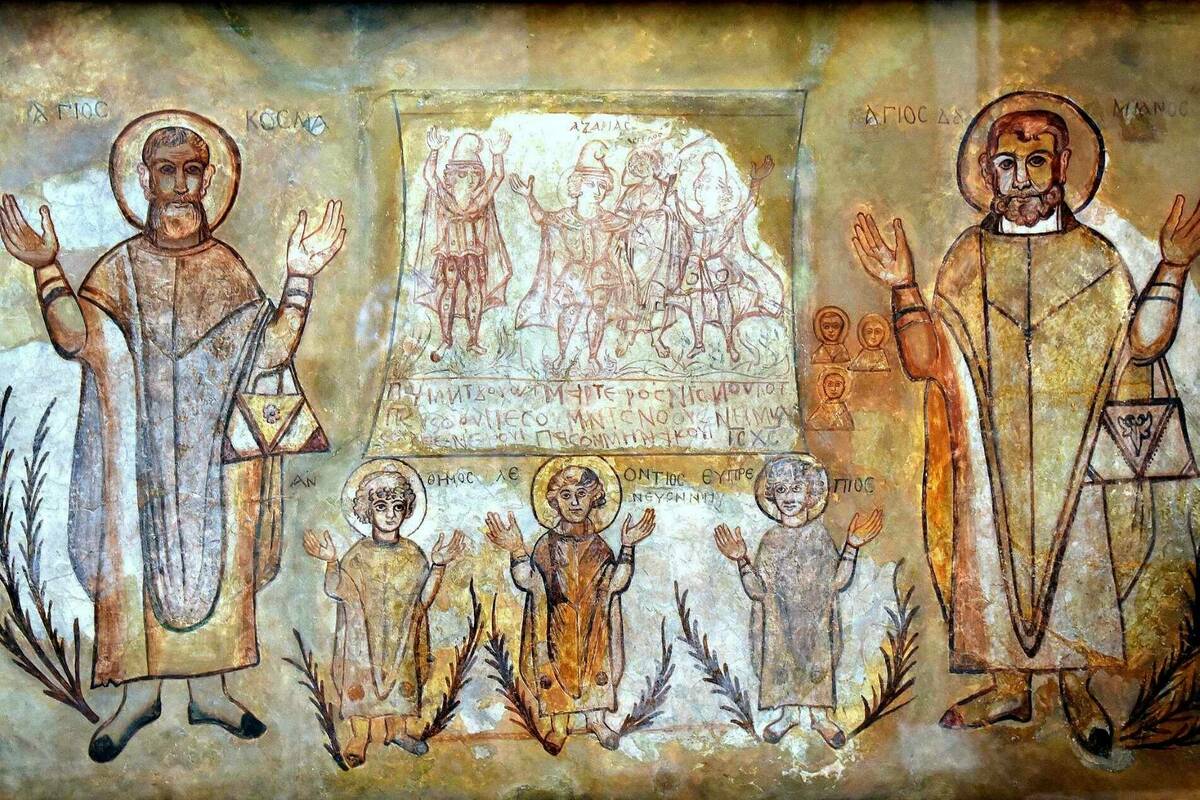

The illogical argument just mentioned has a kind of sense—it seems like persecution could be a sign that one is a Christian—because there are passages in the New Testament that associate the life of the Christian with persecution. The first passage comes from the beatitudes, whereas the second comes from St. Paul’s letter to his disciple Timothy, and they are fundamentally complementary.

- Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness' sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

- Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you. Yea, and all that will live godly in Christ Jesus shall suffer persecution.

Paul’s statement is more straightforward, so we will begin with it. All who “live godly in Christ shall suffer persecution.” It is that simple. As Paul crosses the finish line of the Christian life, he informs Timothy that the Christian life entails persecution. To reinforce his point, Paul provides several examples in the rest of the epistle. Paul’s statement is meant to be preparatory: if you (Timothy) live a godly life, prepare yourself for inevitable persecution. We can imagine Timothy tracing the logic of Paul’s statement.

If you live godly in Christ, you shall suffer persecution.

I live godly in Christ

Therefore, I shall suffer persecution.

If Timothy chooses to follow in Paul’s footsteps, he will become victim to the same kind of mistreatment. However, Timothy would be wrong to think that if he were currently suffering persecution, he was therefore godly in Christ. Timothy could wrongly interpret persecution as a sign that he is imitating Paul and Christ which would be to affirm the consequent.

If you live godly in Christ, you shall suffer persecution.

I suffer persecution.

Therefore, I live godly in Christ.

This train of thought mistakenly assumes that godly living is the only thing that entails persecution. But, as everyone knows, non-Christians are persecuted for many reasons in many different situations. Timothy’s present persecution might be the promised effect of his godly living, but it just as well might not be. Even though persecution comes with the Christian life, its appearance cannot give anyone certainty that they are being a true Christian. The consequences of Christian living cannot be used as verification of it.

But Paul’s statement says nothing of the future reward that the two beatitudes do, and Jesus’s words more explicitly associate persecution with blessedness. As is the case throughout the gospel, Jesus inverts the wisdom of the world (the belief that discomfort and oppression are undesirable and should be avoided when possible), teaching his followers that to be persecuted for his sake is a blessing in the scope of eternal life.

The passage in Matthew addresses a hypothetical present experience (someone suffering for righteousness’ sake) and prepares them for a guaranteed effect in the future (theirs is the kingdom of heaven). The “righteous” woman who is persecuted because she is righteous claims the kingdom of heaven. In the second beatitude quoted above, Jesus teaches his followers that rejection and persecution “for his sake” are desirable because “great is [the] reward in heaven.” His promise is similarly direct: if you suffer for Jesus, then you are rewarded in heaven. If P, then Q. Where people reviled for their loyalty might doubt their commitment, Jesus tells his followers to “rejoice, and be exceedingly glad.”

These beatitudes distinguish between kinds of persecution, promising the kingdom to both, but “great reward in heaven” only to the second. One of the primary distinctions between the two mentioned beatitudes is that the first speaks to all those who are persecuted for “righteousness’ sake,” whereas the second speaks to those who are persecuted explicitly “for his sake.” From these two promises, we can deduce that Jesus acknowledges at least three types of persecution which we can place in order of increasing generality: there is persecution for Christ’s sake, persecution for righteousness’ sake, and plain old persecution (left unaddressed but implied in the beatitudes). The beatitudes do not address persecution that is neither for righteousness’ sake nor Christ’s sake.

We cannot assume that the unnamed third category of persecution garners any kind of reward, though we can safely assume that it exists because “or righteousness’ sake” and “for Christ’s” sake are specific modes of a broader category of persecution, one that likely includes other modes. “Persecution for Christ’s sake” is a species of persecution and “persecution for righteousness’ sake,” and as such, it entails the first two.

Persecution for Christ’s sake is a specific kind of persecution that could also be described as “persecution” or “persecution for righteousness’ sake” without any contradiction. However, the reverse is not true, and we cannot safely assume that any kind of persecution is the specific “for Christ’s sake,” the same way that we can refer to all beagles as dogs but not all dogs as beagles.

Persecution Proves Nothing

Now that we have addressed what these passages from the New Testament do and do not imply, we can consider why it is tempting to think that persecution is a sign of faithfulness. To consider any persecution as validation commits two errors at once: it mistakes persecution for Christian persecution and a specific kind of experience as spiritual validation. All Christians place their hope in the Paschal Mystery, which is to say that they believe that Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection overcome the burdens and effects of their sins and win for them the possibility of eternal life in heaven. Different Christian denominations believe different things about the necessity of individual Christians’ participation in the process of salvation, but every living Christian regardless of doctrine must wait to see the promise of their salvation fulfilled after their death. For this reason, it is incredibly tempting to look for reassuring signs that one will be saved.

But the scripture passages do not perform two consoling functions we might want them to. They do not help readers identify Christian persecution and they do not promote persecution as desirable in itself. It would be nice if the scriptures provided some criteria for when persecution counts as Christian persecution because if they did, then we could absolutely use them as a way to verify that we are living a Christian life. Similarly, if the gospel endorsed all experiences of persecution as blessed and justifying, then anyone could actively provoke and pursue persecution to guarantee themselves salvation.

Neither Jesus nor Paul say anything in these passages about persecution being an indication of your Christianity, even if being persecuted for Christ’s sake puts you in good company with “the prophets that were before you.” Jesus does not say, “when you see that you are persecuted you will know that you are in the company of the prophets.” Jesus merely reminds you that you are in good company if you find yourself persecuted for your faith and works.

In order to know that you are in the company of the prophets, you must be confident in the cause of your persecution, which is to say, you need to understand the reason you are being persecuted. It is natural to ask why we feel the way we do, why this is happening to me when we suffer, especially at the hands of other people. When we look to persecution as a confirmation of Christian living, we misidentify a possible effect or consequence of Christian living as verification of something that we want to be true.[1]

Conclusions

There are some questions that we cannot address thoroughly, but that are worth discussing briefly, nonetheless. First of all, what distinguishes “persecution” from suffering, discomfort, or unpopularity? Persecution is different from other forms of suffering in that it is explicitly social. Especially today, the word persecution means a kind of pain or inconvenience inflicted on one person by another for reasons, and it often implies a kind of continuous and coordinated effort. Unless the form of oppression is articulated for reasons related to one’s Christianity or it is clear from the action or effort that it targets one group of people because of who they are or what they believe, we should be wary of attributing persecutionary intent to the actions. Both history and news from far corners of the world attest to real occasions of Christian persecution, but persecution is much more difficult to identify as an individual American.

But this begs the question, who decides when persecution has occurred? Today, we tend to sympathize with victims or those who want their situation to be understood in terms of victimization. To recognize persecution is to acknowledge imbalanced power, and since persecutors rarely justify their own actions in those terms, observers and victims are left to speak up and acknowledge unjust abuse.

In a 2018 article, Abigail Favale discusses how victimhood has become a indicator moral authority, a position that has become tempting to Christians. She rightfully notes that in a moral paradigm oriented by victimhood, “moral worth is relative [and] dependent on something external.”[2] This is to say that victim status, or, for our purpose, persecuted status, depend on a first-hand account of someone else’s actions, “I am a victim, and I am persecuted to the degree that I recognize someone else’s actions as violating me or singling me out in some particular way.” Wesley Walker similarly notes that “the victim-complex is boisterous because it must call attention to itself” in order to persuade anyone else.[3]

The second question worth considering is, how could one tell that righteousness or fidelity to Christ cause an instance of persecution? The New Testament promises the faithful Christian that they will be persecuted for their faith, and it also promises them that such persecution is “blessed.” As we discussed, all faithful followers of Christ will be persecuted, but not all those who are persecuted are Christian; so, persecution cannot be understood as an indication that one is living faithfully unless one knows that the reason that one is persecuted is his or her Christianity. The reasons for one’s persecution can be quite hard to identify, just as it might be hard to disentangle our own intentions for doing one thing or another. As a rule, it is unwise to attribute motivations to people unless there are clear signs to prove it.

If, for instance, a child was bullied by his peers because his family was large and poor, it would not be logical to deduce that the child is persecuted for his righteousness or faithfulness, even though the child’s status might be related to his family’s choices motivated by their faith. The bullies are mistreating him for qualities related to his Christianity, but from their perspective, Christianity likely does not factor into their singling him out. Neither the bullies nor any observer would say that the boy is bullied because he is Christian. They would all agree that he is bullied because he is poor, regardless of what choices contribute to his poverty.

Now let us consider a more common example: if people find themselves being ridiculed and oppressed because they voted in support of the pro-life agenda, is it reasonable to say that they are being persecuted for righteousness’ sake or Christ’s sake? It would seem reasonable to infer that one is being persecuted for both, if Christian doctrine and the virtue of justice are among the primary reasons that those people voted for one candidate. Without endorsing the actions of the persecutor, however, we can see that the pro-life voter has confused his reasons for supporting voting pro-life with the persecutor’s reasons for mistreating those who vote pro-life. The abuser likely does not act with purely noble motivations, but the abuser and any outside observer would certainly agree that the oppressor is not victimizing pro-lifers because they are Christian. Beliefs in Christianity, pro-lifeism, and particular candidates may hang together but they are not equivalent, nor do they necessarily entail each other.

The hypothetical pro-life scenario brings me to the final more local point I want to make about the Christian pattern of affirming the consequent. There are many, many reasons a person could be persecuted, and there are several forms of social discomfort that can be mistaken for persecution. Everyday inconveniences, social duties, disagreements, impoliteness, and many other experiences can all be misunderstood by the suffering person as persecution. Unless it is the case that an instance of persecution can be understood as being motivated by someone else’s attitudes towards one’s Christianity, it is probably best not to assume one’s virtue or faith are the reasons for the mistreatment. I tentatively suggest the formula: If what someone else finds intolerable in you is your Christianity, then you are persecuted for Christ’s sake.

We should be cautious in calling anything persecution for fear of cheapening the genuine persecution of other Christians and to ensure that we do not assume malicious intent on the part of other people involved. And, more to the point of this argument, if we determine that we are in fact being persecuted, we should patiently discern if our righteousness or Christianity are the reasons for that persecution. If they are, we can take consolation in our company with the prophets and hope in Jesus’s promise. If they are not, we can unite that suffering with our Savior’s passion. In neither case, however, can we take that experience of persecution to be proof of our faithfulness.

The Gospel distinguishes between the consequences of Christian living and the confirmations that one is in fact being a Christian. Followers of Jesus can anticipate certain experiences because his words are true. Those experiences, however, cannot be used as psychological justifications and for rationalizations of our Christianity. We cannot consider resistance to be a sign of righteousness, even if we know that persecution and resistance are part and parcel of the Christian life. If we want to prove our Christianity to ourselves and others, persecution is a false friend. Choices made in compassion, self-sacrifice, and love are better signs of Christian living than anyone else’s reactions and responses.

[1]. In making this argument, I run the risk of being misunderstood on the topic of Christian suffering. To be clear: interpreting persecution or suffering as the sign of a Christian living is very different from allowing suffering to sanctify us. If we are particularly cognizant of God’s involvement in our lives, we can choose to align our suffering with his suffering for our sins and believe that it is part of his plan for our salvation. It is not superstitious to believe that God’s hand is in our lives, and that events, encounters, and experience are brought about through his providence. All suffering can be sanctified, but not all suffering is persecution, nor is all persecution blessed.

[2]. Abigail Favale. “Dignity or Victimhood?.” Cynthia L. Haven has also argued that the prescient insight of the philosopher René Girard is our unflinching tendency to cast ourselves in the role of victim as we simultaneously persecute others in “René Girard and the Present Moment.”

[3]. Wesley Walker. “The Difference Between Martyrdom and a Victim-Complex.”