For the Son of God to become man means that it was actually the person of the Son (in his esse personale) who was truly the experiencing and acting subject within his human existence as man. The subjective identity of the man Jesus, who this man was, was God the Son. Moreover, the Son, as the sole subject, actually experienced the whole of human life and acted in a fully human manner from within the confines of his own human “I.” This assures the authenticity of his human experience and action. Last, I argue elsewhere that the Son did not assume some generic, antiseptic, or immunized humanity, which would quarantine him from our sinful human history and condition, but rather he assumed a humanity which bore the birthmark of sinful Adam, and so entered into our human history as one like ourselves.

All of the above must now be taken to the event of the cross so as to discern the soteriological significance of Jesus's death. I now want to argue that on the cross the Son of God as man simultaneously performed three actions:

- He assumed our condemnation.

- He offered himself as an atoning sacrifice to the Father on our behalf.

- He put to death our sinful humanity.

Assuming Our Condemnation

Sin, it must be remembered, is contrary and hostile to all that is good, holy, and loving, and so is an affront to the perfectly good, holy, and loving God. As such the unredeemed (or unrepentant) sinner reaps sin's intrinsic and inevitable consequence—separation from God. God and sin cannot abide with one another. Biblically, physical death gives expression to the deeper death of having been separated from the God of life.

However, while sin had made humankind God's enemies, the Father's response to sin was not that of allowing humankind to suffer its just fate. Rather, the Father's salvific goal reconfirms his plan first inaugurated at the dawn of creation. He desires that we share fully in the eternal life of the Trinity (see: Eph 1:3-14). Being conformed into the likeness of his Son through the Holy Spirit, the Father becomes our Father. The Trinity then is the source and goal both of creation and redemption. Thus, in love, the Father sent his Son into the world so that we might not perish in our condemnation, but have eternal life with him (see: John 3:16; 1 John 4:9). This is the point of our soteriological departure.

First then, in this “sending” the Son assumed not only our sin-marred humanity, but also, in his death, the full weight of its condemnation. The Father sent “his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, and to deal with sin, he condemned sin in the flesh” (Rom 8:3). The cross actualized the Father's condemnation of our sinful flesh, for sin itself, “when it is fully grown, gives birth to death” (James 1:15). “The wages of sin is death” (Rom. 6:23; see Gen. 2:17). Even though Jesus never personally sinned (see Heb 4:15, 1 Peter 2:22, John 8:46, 1 John 3:5), yet the Father, for our sake, “made him to be sin who knew no sin” (2 Cor. 5:21 ). This he did both in sending the Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and in having him mount the cross upon which sin was condemned. Thus the Incarnation leads directly to the cross, for the cross expresses the Son's complete solidarity with our sinful condition and its condemnation. The Son of God was truly born under the law, and thus under its curse (see Gal. 4:4).

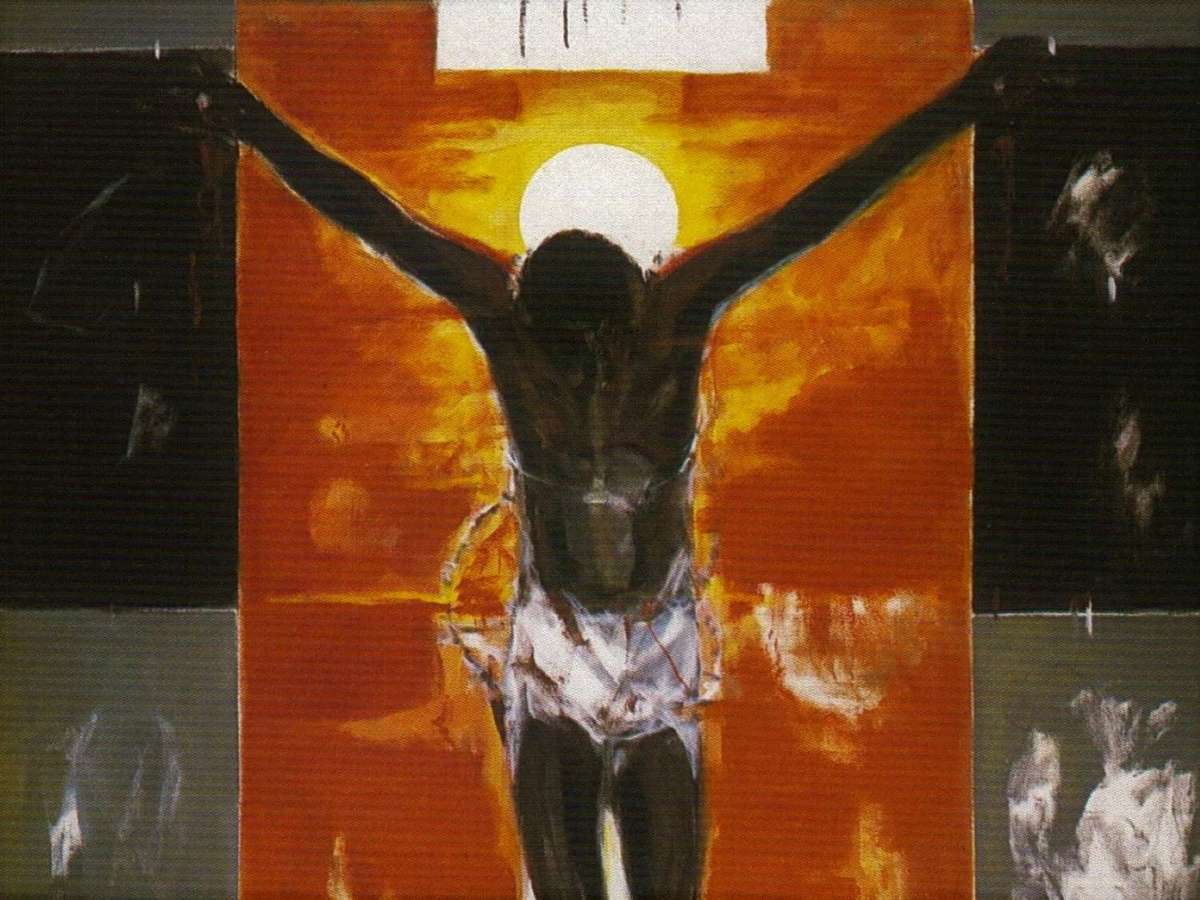

This condemnation, due to sin, is nothing less than being separated from God. In the garden of Gethsemane, it was this cup of condemnation that the Son, in agony, saw set before him in its full horror, and ardently implored the Father to remove (see Matt 26:36-46; Mark 14:32-42; Luke 22:39-46; John 12:27; Heb 5:7-9). Thus, the Son's human cry from the cross “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (Matt 27:46)—was no mere charade, but the authentic lamentation of one who was suffering the wages of humankind's sin. The Son of God truly tasted death for us, not just the suffering of physical death, but the deeper “second death” of being separated from God (see: Heb 2:8-9). Having been “made sin,” the Son of God, as man, literally suffered the pains of hell, for hell is simply the experience of the absolute loss of God's loving presence.

Moreover, the loss of God's loving presence is experienced not as a mere absence. This would indeed be horrendous in itself. But, more positively and abhorrently, the divine Son actually experienced, as man, the very wrath of God. While this must be properly nuanced, yet it must not be mitigated, for here we discover the depths to which the Son was willing to descend so as to seize the extreme limit of human suffering.

As stated above, sin is an act contrary to all that is good and holy, and thus an affront to the all-loving God. Thus sin is a free act of separation—the separating of oneself from God. It is this sinful act of separating oneself from God which literally creates hell, for that is what hell is—being separated from God. If this separation is not healed, the sinner experiences this separation not merely as the absence of God, but more emphatically as his actual abandonment. “To be abandoned by God” adds to the conception of “separation” the positive notion of God's wrath, for such an abandonment testifies to God's righteous judgment upon the sinner. There is no other manner in which the sinner can now experience the absence of God, not because God has changed from being a loving God to being a wrathful God, but because the sinner now literally embodies all that is ungodly.

To experience the wrathful abandonment of God is but the self-verification of what one has indeed become: ungodly. Obviously then, to experience the wrath of God is not an experience of God avenging himself in rage or capriciously punishing in anger. God does not hate the damned. God remains the God of love, but within and because of his love, he hates and despises what the sinner has become. God is experienced as being wrathful, for God judges or sanctions that such a separation is the proper and only just consequence (and so punishment) of sin, not because he has so said, but because sin itself has so said. The wrath of God is simply God's approval of what sin itself rightfully demands.

It is the wrath of God in this sense, as the ultimate necessary consequence of the playing out of sin in the presence of the good and holy God, which the Son of God experienced. Having assumed our condemnation, he experienced the wrathful abandonment of God. He plunged to these depths of suffering in a manner that was genuinely human, and not in some abridged, and so humanly inauthentic, divine manner. He stood in our stead, and he did so out of love for us, that we might never encounter such a tragic end. In conformity with the ancient patristic principle, he assumed our condemnation that we might be saved from it.

It is difficult to overstate this point, and it is equally difficult to appreciate its full significance. Because of our present sinful condition and, more so, because of our own personal sin, we, as human beings, are incapable of experiencing full communion with the loving Father. However, the Son of God, while he assumed a humanity marred by sin, nonetheless lived in perfect obedience to the Father, and so humanly experienced, as far as is humanly possible in this life, the consummate love of his Father. Only when one has experienced the fullness of the Father's love, can one fully know the utterly depressing agony and despair of being abandoned. But how, in taking on and experiencing our condemnation, did the Son of God save us from it? Again, it is not enough for him just to have experienced the ultimate in human suffering.

Offering an Atoning Sacrifice

Jesus in his death did not just experience our condemnation. Rather, his death also achieved humankind's reconciliation to the Father. One of the common refrains throughout the New Testament is that Christ “died for us” (see: Rom 5:6 and 8, 14:9 and 15; 1 Cor 8:11, 15:3; 2 Cor 5: 14-15; Gal 2:20-21; 1 Thess 5: 10; 1 Peter 3:18) or that “he gave himself up for us” or that “he was given up for us” (see Matt 20:28; Mark 10:45; John 3:16; Rom 4:25, 8:32; Gal 1:4, 2:20; Eph 5:2 and 25; Titus 2:14). Humankind, not God, is the beneficiary of Jesus's death. Through his death God is not reconciled to us, but we are reconciled to God. But how does Jesus's death alter our relationship to God and in so doing change us? Here we must examine the sacrificial nature of Jesus's death.

The biblical understanding of sacrifice can only be understood within the equally biblical context of God's relationship to his people and the sin that violates that relationship. While sin initially broke humankind's relationship with its Creator, God established a covenant with Israel. This covenant was ratified by a sacrifice. Moses, in the sprinkling of the blood (the symbol of life) upon the altar and the people, manifested that through this covenant God and Israel would share a common life (see: Exod 24).

Yahweh would be the God of Israel and Israel would be his holy people (see Deut 7:6, 14:2 and 21, 28:9). The commandments embodied the holy life that Israel was to live. It is sin that repudiates this holy life and so transgresses the covenant. Sin itself, if not fully the sinner, embodies all that is ungodly. In itself it knows no goodness, justice, truth, love or holiness. The sinful act not only repudiates them, but also positively wars against them in order to achieve, at whatever the cost to them, its own selfish ends. This is the arrogance of sin. It warrants neither God nor others but itself alone.

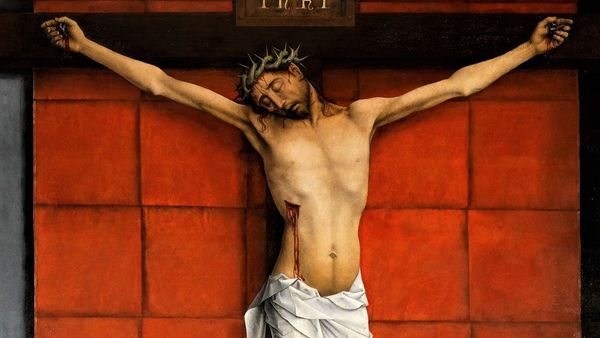

In contrast, sacrifice, as a means of atoning for sin, is always seen within the Old Testament liturgical rites as the act whereby human beings lovingly offer something to God, for example a lamb, that is pure and unblemished, and so precious. The act of sacrifice outwardly represents and expresses, and so embodies, the interior desire to atone or make reparation for the sinful actions committed so as to be cleansed of ungodliness with its condemnation, and so assume once more a godly state within the covenantal relationship. The sacrifice, by its very nature, entails suffering, for one suffers the loss of something precious, but here the suffering is experienced as something good and right, for one has lovingly offered it to God, instead of claiming it for oneself. It is the repentant or atoning love with which the sacrifice is offered that makes it meritorious, and it is the suffering (not of the animal but of the one making the offering) contained within the sacrifice which manifests the depth of the love. Only within this Old Testament understanding of sacrifice can we discern the sacrificial nature of Jesus's death.

Jesus stated that “the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as ransom for many” (Matt 20:28; Mark 10:45). Jesus ransomed us in the sense that he freed us from our condemnation—the slavery of sin, the dominion of Satan, and the fullness of death. He did so by offering, in our stead and on our behalf, his life to the Father. But why did Jesus have to become a sacrificial offering on our behalf in order to ransom us?

It was not the Father who, in righteous anger, vindictively imposed such a sacrifice, but rather, as prefigured in the Old Testament, sin itself demanded such a sacrifice. Only a pure, holy and loving sacrifice of atonement could ultimately free us from sin's condemnation, and so reconcile us to the Father. It was actually the Father who provided, in the person of his incarnate Son, the means of our reconciliation. “All of this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ” (2 Cor 5:18-19; see: Rom 5:10-11; Col 1:19-20). It is God himself who “has rescued us from the power of darkness and transferred us into the kingdom of his beloved Son, in whom we have redemption the forgiveness of sin” (Col 1:14). God himself obtained the Church “with the blood of his own Son” (Acts 20:28; see: Titus 2:14).

Jesus assumed the debt of sin in assuming our condemnation, and he paid the debt of sin in offering his life in love to the Father on our behalf (see: 1 Cor 6:20, 7:23). He freed us from the debt that sin imposed. While Jesus offered himself in sacrifice to the Father, such a sacrifice was offered not for the Father's benefit, but for ours. We, not the Father, are the beneficiaries of such a sacrifice. “You [Jesus] were slaughtered and by your blood you ransomed/purchased for God saints from every tribe and language and people and nation” (Rev 5:9). On the cross Jesus not only became “a curse for us” in assuming our condemnation, but he simultaneously redeemed us “from the curse of the law” through his sacrificial death (Gal 3:13). Jesus set aside our condemnation by “nailing it to the cross” (Col 2:14).

Thus, Jesus is the lamb of God (see John 1:36; Rev 5:6, 12), who takes upon himself all sin with its punishment (see: Isa 53; Acts 8:31), and offers his life blood in expiation (see Lev 17:11, 14). Jesus “loves us and freed us from our sins by his blood” (Rev 1:5). Equally, he is the Passover lamb of our redemption (see: Exod 12:46; John 19:36; 1 Cor 5:7). “You know that you were ransomed from the futile ways inherited from your ancestors, not with perishable things like silver or gold, but with the precious blood of Christ, like that of a lamb without defect or blemish” (1 Peter 1:18-19). Because Jesus, as the lamb of God, offered his life (blood) to the Father to free us completely and forever from the bondage of sin, so his blood is equally the blood of the new and everlasting covenant with the Father (see Matt 26:26-28; Mark 14:22-24; Luke 22:19-20; 1 Cor 11:23-25).

Furthermore, within the Pauline corpus, “Christ died for the ungodly,” for it was “while we still were sinners [that] Christ died for us” (Rom 5:6, 8). Thus, “we have been justified by his blood,” and “saved through him from the wrath of God,” for “while we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through the death of his Son” (Rom 5:9-10). The logic is straightforward: Sin made us ungodly enemies of the Father and so subject to his wrath. Jesus justified us through his sacrificial death on the cross, thus reconciling us to the Father. Again, it is humankind, and not the Father, who reaps the benefits of Jesus's sacrifice. His atoning sacrifice allows us to be once more at one with God. In fact “God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross” (Col 1:20). Thus, “in him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses” (Eph 1:7). Humankind is reconciled to the Father and made holy “through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as an expiation by his blood” (Rom 3:24-5). While living within our sinful condition, Jesus reversed or counteracted the sinful disobedience of humankind, by living under obedience to the Father even unto death. His one righteous act of obedience brought “acquittal and life for all” and so “many will be made righteous” (Rom 5:18-19).

The Letter to the Hebrews confirms that, while the Son of God was of our same sinful stock (see Heb 2:11, 14-15), and so was tempted in every way, yet he nonetheless lived, unlike us, in complete obedience to the Father and so never sinned (see Heb 2:17-18, 4:15). The Father prepared a body for his Son, and it was within that body that the Son declared: “Lo, I have come to do your will, O God,” and “it is through that will that we have been sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus Christ once for all” (Heb 10:5-10). It was through the Son's human will, through his human “yes” to the Father, that we have been sanctified. Jesus himself is the High Priest and victim for he offers himself for our cleansing from sin. “He entered the Holy Place, not with the blood of goats and calves, but with his own blood, thus obtaining eternal redemption” (Heb 9:12; see: 9:22). It is only because the Son offered his human life through the Holy Spirit that such an offering is holy and so efficacious. If the blood of animals was able, in the past, to purify the flesh, “how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to worship the living God?” (Heb 9: 14).

From this brief exposition of the sacrificial nature of Jesus's death, a number of points must be highlighted. I especially want to note the various causal connections, that is, the efficacious nature of Jesus's passion and death.

First, Jesus's sacrifice of himself was a twofold act of love. It was an act of sacrificial love offered to the Father, for in love the Son offered his own life to the Father to atone for and so offset or, literally, counteract all humankind's ungodly sinful acts. This act of love was done out of complete obedience to the Father for it was ultimately the Father who was reconciling the world to himself through his Son. Moreover, it was an act of sacrificial love performed out of love for humankind, for the incarnate Son did, out of love for humankind, what it could not do on its own behalf. It was this twofold perfect act of love which made Jesus's sacrifice meritorious. Moreover, it was the suffering of death contained within this sacrifice, the very handing over of his holy and precious life on our behalf to the Father, which embodied and manifested the consummate depth of his love, so making it supremely efficacious.

From the above we must, second, grasp the causal connection between the atoning nature of Jesus's sacrificial death and its reconciling effect. In offering himself out of love for us, the incarnate Son offered a sinless, perfect, and holy sacrifice to the Father, one that would fully and adequately express humankind's reparational or atoning love in the face of sin. Thus, this sacrifice atoned for all the sin of humankind, but in so doing it effected a reconciliation with God. This is why Jesus's blood is the blood of an everlasting and unbreakable covenant. Jesus's pure and holy sacrifice so abundantly atoned for sin that there is no longer any sin that has not been dealt with. Every human being can reap the benefit of Jesus's atoning sacrifice and so be reconciled to God within the new covenant established in his blood.

Third, it must be equally clearly perceived that, while it was truly the person of the Son who offered the sacrifice, he did so, in accordance with the truth of the Incarnation, as man. The merit of the sacrifice, which expiated our guilt and condemnation thus reconciling us to the Father, was precisely located in the Son's human love for the Father and for us. The Son of God then did not offer his divine life to the Father in a man. If this were the case, it would demand that his human life, with his human love, and the suffering that that love entailed, were of no salvific value. They would become mere symbols attesting to what the Son was doing as God. It must be the Son of God as man who lovingly assumed our condemnation and, as one of us on our behalf, who offered his human life in love to the Father. The merit of this love is actualized and expressed in the extent of the human suffering he willingly endured. In his suffering, the very Son of God actually experienced, as an authentic man, the depth of humankind's sinful plight, and he equally experienced as man the price that needed to be paid in order to rescue us from it—the atoning sacrifice of his own human life. The humanity of the Son, the humanity that was offered to the Father, was the efficacious means through which redemption and reconciliation was obtained.

Fourth, Jesus triumphed over or vanquished the suffering of our condemnation by or through the sacrificial suffering of offering his life to the Father on the cross. This causal connection, to my knowledge, has never been adequately discerned. Jesus suffered our condemnation on the cross and, in the very same act of assuming our condemnation, he simultaneously and equally offered, in love, his life to the Father as an atoning sacrifice on our behalf for that condemnation. His sacrificial offering of his life to the Father on our behalf transformed the suffering of our condemnation into an act of freeing us from such condemnation. This was due to the perfect love simultaneously contained and expressed within both aspects of this one act of suffering death on the cross. In death Jesus assumed and so suffered, out of love for us, our condemnation, and, in the same suffering of death, Jesus lovingly offered his life to the Father out of love for us. The love contained and expressed within the sacrificial suffering vanquished the suffering of our condemnation, so freeing us from it.

Fifth, as I have emphasized above, Jesus's sacrifice must not be seen as placating an angry God, as if he were an offended person, who demanded in justice, to be propitiated and appeased. It is sin itself, in conformity with the justice of God, that has justly imposed upon humankind a debt, and it is this debt that is expiated through the death of Jesus. Jesus rightly offered his life as a sacrifice of atonement to the Father for our benefit and not his. Through his sacrificial death he made reparation for us. Such a sacrifice vanquished our sin and our condemnation, and in so doing enabled us to be reconciled to the Father.

Putting to Death Our Sinful Humanity

Simultaneously with the experience of complete abandonment and the offering of his human life in sacrifice to the Father for the forgiveness of sin, the Son also put to death our old sinful humanity, the same sin-marred humanity that he himself had assumed. “We know that our old self was crucified with him so that the body of sin might be destroyed, and we might no longer be enslaved to sin” (Rom 6:6). On the cross our sinful flesh died, for that is the flesh that the Son assumed.

Paul also states that “in him also you were circumcised with a spiritual circumcision, by putting off the body of the flesh in the circumcision of Christ (Col 2:11; see: 2 Tim 2:11). “Flesh” for Paul, similar to “the body of sin,” connotes the whole person mastered by the disposition of sin with its passions and desires. Jesus's death on the cross was the true and authentic circumcision for it was there that he was freed of our sin-marred humanity.

Now the reason that our sinful flesh died on the cross is twofold. It died for in Jesus it had experienced its just condemnation—not only physical death but also the absence of God's presence. Simultaneously, it was offered lovingly to the Father in reparation for sin. “One has died for all; therefore all have died” (2 Cor 5:14). Because the Son of God lived a pure and holy life of obedience to the Father as a member of the sinful race of Adam, with his own sin-marred humanity, the loving offering of that humanity on the cross brought about its demise. Our sinful human nature was put to death for the Son of God transformed it into a pure, holy, and loving sacrifice to the Father.

From our examination of these three soteriological truths we have seen that Jesus not only suffered, but that in so doing he also confronted the very source of all suffering: sin. This is what makes Jesus and the suffering he endured unique. All human beings suffer because of sin. The incarnate Son also suffered because of sin, though not his own. But in suffering Jesus freed himself and the whole of humankind from suffering's cause: sin. He did this by enduring the full consequence of sin: our sinful condemnation. More positively, he suffered in love, for he offered his own life as a sacrifice to the Father on our behalf.

Together these resulted both in the death of our sinful nature and in our being reconciled to the Father. On the cross then, Jesus thoroughly dealt with sin. However, this was not the only result of the Son's death on the cross. Because his sacrifice was the loving offering of his holy life by which we were reconciled to the Father and so set free from sin with its condemnation, Jesus won for us the new resurrected life of the Holy Spirit.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is an excerpt from Does God Suffer? It is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. You can read our excerpts from this collaboration here. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.