Overture on Silence

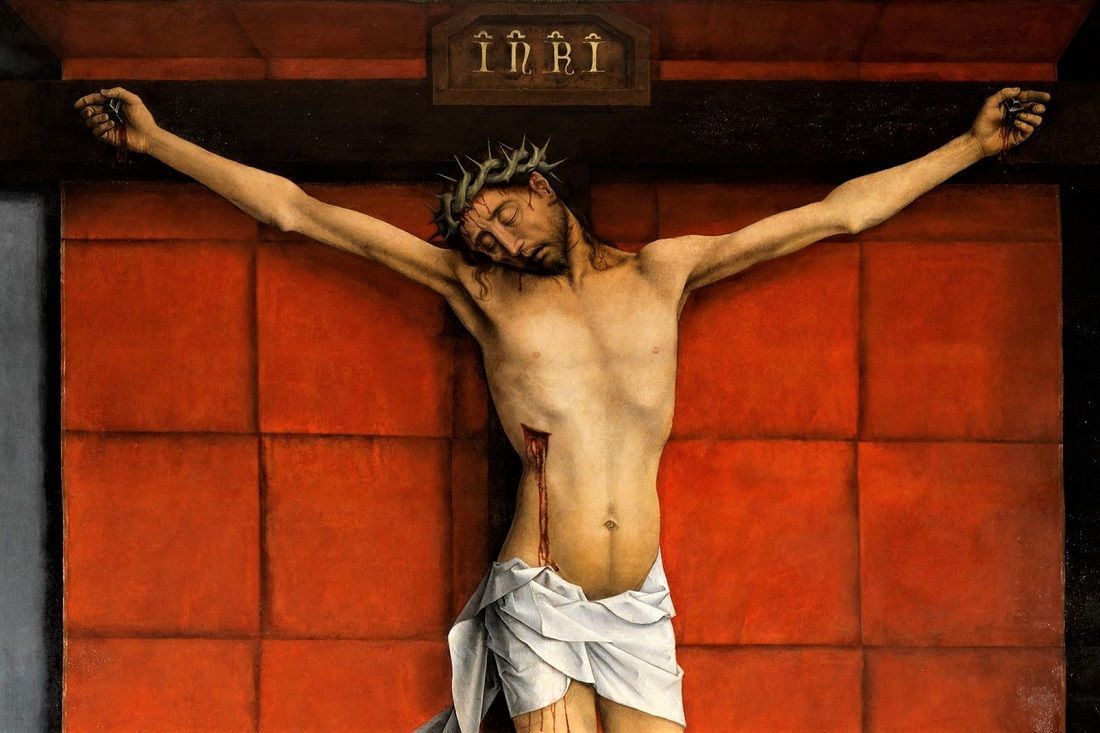

There are many kinds of silence: the stony silence of hatred, the crimped silence of hurt, the directed silences of envy and contempt, the silence that is the pause between our chattering and nattering, the concentrated silence of an attempt to find oneself in the scattering of oneself across work and home, task and function, busyness and the distractions we pile on in our leisure, the silence that is the time of planning and plotting, the silence rutted by fantasy, the silence that is the relief of withdrawal from a worn day with even more worn words, the silence before one drifts off to sleep, the silence which marks our having been beaten down and become abject, and the silence that is the acceptance of one’s death now coming in from the wings. There is happily also the silence of waiting on a sign that we are loved, the silence from which a work of art emerges and returns, the blessed silence from which scripture comes and the silence with which it is received. And even more happily for those of Catholic and Orthodox persuasion there is the contemplative silence that marks our meeting with God who is before, after, and beyond words. And there is the great silence of the Cross that we can only meet in silence and pinched awaiting, which is a background at the very least, and sometime even the foreground, of the deepest and most fruitful silence of all, the Father’s generation of his own Son in and as Love, which is the ground of the universe and the fountain of our wild hope that the crooked things of the world and the bent back of our own desire will be straightened. With respect to this last silence we can only answer in and with a silence that is rich, deep, ebullient, and joyful.

Silence is a general theme of the Christian mystical tradition, and this Christian mystic and saint, this spiritual master of the 16th century, Saint John of the Cross, knows them all. He knows the venial silences as well as the ordinary ones, and he also knows the silences that truly count. Thus, he knows and focuses on the silence that unites one with the great silence of God unspeakably uttering his Word. He shows that he knows the silence of illumination by eloquently etching the silence in which one is granted an intimation of divine presence, even if one impossible to hold. And he is a familiar with the depth, height, and edges of the silence in which, despite our apparently successful efforts to quell distraction and be ready for a visitation, one experiences nothing, or one experiences the absence rather than the presence of God. More of this shortly, but first I want to say something about drama, which only seems to be out of place talking about saints in general and this saint in particular. There is a drama of life, with forward momentum and setback, with surprising gifts and unexpected frustrations. This drama of life is connected with the drama of love, in which we give and receive love or find ourselves unable to give or receive, in which we love the right or wrong thing, the right or wrong person. And there is the drama of the spiritual life which, on Saint John of the Cross’ account, displays the same pattern. The drama of life and love that is our lot and the drama of spiritual life and love are related by analogy. It is this analogy that made Saint John suspect to some, since they feared that he untied the relationship between spiritual life and liturgy and spiritual life and the Church, was psychologizing the spiritual life and in effect reducing it to our capacity to have special experiences that just the very few have had and very few will ever have. It was this analogy that equally made Saint John of the Cross a hero to some: finally, it was thought, we can celebrate and enjoy a reflection on spiritual life capable of making sense to us without the apparatus of the Church or doctrine. We have, if you like, the outline of a secular or at least unaffiliated mystic and saint. Thomas Merton, however, thought that one could underscore the existential and experiential side of Saint John of the Cross while thinking that the great Carmelite was not only a loyal son of the Church, but impeccably orthodox across the entire arc of Catholic doctrines, not excluding the doctrine of the Trinity. We could, and perhaps should, think of Saint John of the Cross as belonging to two different but related spaces. This mystic and spiritual master is, indeed, from the heart of the Church and cannot be explained except by appeal to it. Moreover, he has imbibed all the tradition available to him. Augustine is hugely important, particularly his Confessions, On the Trinity, and Commentary on the Psalms; Aquinas is a loadstone from his theological studies in the university of Salamanca; and John of the Cross knows not only the work of Pseudo-Dionysius, the master of unknowing and before Saint John of the Cross the master of silence and darkness, but also the long reception of the extraordinary work of the unknown Syrian monk who shows the learner the way towards God through language, its destruction, and the experience in silence of divine silence where speech has become unnecessary. Still, as much as any other figure up to, and maybe beyond, the 16th century Saint John of the Cross speaks also to those who are at the margins of Christianity, either in a state of separation from the Church, but perhaps still in a state of belief, or outside the Church entirely, but perhaps wanting to believe, who cry out with the father of the possessed boy “Lord help thou my unbelief.” Saint John of the Cross is, I would submit, the mystic and saint of the threshold.

Saint John of the Cross in Context and the Basic Outline of the Journey of Love

I have not yet properly introduced this saint and connoisseur of silence. Saint John of the Cross is a 16th century Spanish saint, mystic, born in 1542 near Avila, who died in 1591, who was imprisoned from time to time by Carmelites who thought his reforms went too far, who was beatified in 1675 (Clement X), who was canonized in 1726 (Benedict XIII) having gone through the juridical process of canonization. He was also, and non-incidentally, the friend of the other great mystic and saint, Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), for whom, though younger, he served in the role of spiritual director. Like her he is a spiritual master, and like her (1970) declared a doctor of the Church (1926 by Pius XI) in the 20th century. If any pair were complementary spirits it is they: she a spiritual master with a genius for organization and a penchant for being a public figure; he a spiritual master whose genius lay in his elaboration of the spiritual life with all the artistry and passion of a poet with a fine-tuned logic that was in its own way as meticulous as that found in Aquinas. Saint John of the Cross is the writer of spiritual classics such The Dark Night of the Soul, Spiritual Canticle, Ascent to Mount Carmel, The Living Fame of Love, in which is articulated the path to the union with God that is the true goal of human life that surpasses understanding. The experience of union with a triune God who unfathomably and lovingly gives birth to his Son can only be in darkness and silence. As in all things spiritual, emphasis is, indeed, important and one could argue that few in the spiritual and mystical tradition have spoken in quite such an apophatic way of the self’s ultimate encounter with God. This is not untrue. Still, intellectual honesty forces us to face the fact that the union of a self with God in darkness and silence is a trope in the tradition of mystical theology. We find it in Pseudo-Dionysius (6th c.), even earlier in Gregory of Nyssa (4th c.), in Meister Eckhart (14th c.), and the author of the Cloud of Unknowing (14th c.) to name but a few. This is not to downgrade John’s marvelous achievement, but rather to look for it elsewhere.

One of the crucial identifiers of John’s speaking of the mystic way is to say that all that is genuine in it is out of sight and occurs in the night (noche) that is usually qualified as a “dark night” (noche oscura) or “the black of night” (aunque es de noche). Night is everywhere in the poetry and mystical commentaries of Saint John of the Cross. The discovery that it is God we seek occurs in the night; it occurs only when we have temporarily managed to suspend our routine way of thinking and have been temporarily detached from the all too determinate objects of our desire, whether fame and fortune, sex, power to wield over others and society, or envy and mimetic desire. In the night we discover that our deepest desire has a different aim or perhaps even an aim for the first time. Since this aim is not determinate like all other aims, one needs a guide for the journey in which there will be a struggle to keep the desire pure and rid oneself of all the attachments that inhibit, misdirect, or occlude this pure desire. In terms of basic theological structure, all of the texts of Saint John of the Cross are Augustinian. What defines us is the orientation of our desires or loves, whether we look for satisfaction by possessing some good in the world that both props up and feeds our self-love (amor sui), or love is aimed at God in whose spousal embrace we become our true selves (Ascent to Mount Carmel, 1.4-6). Saint John of the Cross spends plenty of time elaborating the spousal union in contemplation beyond knowledge and will, certainly enough for us to grasp why it would motivate us to curb our passions, divest ourselves of attachment, and be so extraordinarily scrupulous in ferreting out when and where the “world” that we boast of having overcome leeches back in. This ever so brief union, which Saint John of the Cross is supposed to have experienced on a few occasions, is worth all the difficulties and deprivations that we experience, and, though Saint John of the Cross does not draw our attention to it, this experience of union is a symbol of that union with God in the next life of which only a poet as great as Dante can risk elucidating. Of course, there is no guarantee that even with the destitution of senses, natural affections, and imaginings or fantasizing, and the destitution in my spiritual life, this spousal union will occur. The spiritual life is risky and all that can be achieved is that one is open to the triune God who makes in silence the last as well as the first move: one would never be seeking God in the first instance without God’s initiative. The last move of God as well as the first move of God is the move of grace, which by definition is beyond our deserts and which cannot be attained in and through what has come to be called the “technology of the self.” Union with God is not a “work”; it is not our accomplishment. In insisting on this it might seem as if Saint John of the Cross is responding directly to the Reformation. The claim is not without merit. Yet, it is far more likely that John is continuing the dominant emphasis in the Catholic spiritual and mystical tradition, even if occasionally some spiritual masters in that tradition (i.e. Eckhart) seemed to suggest the breaking down of the self and the openness to God serve as something of a guarantee for union. Grace, God’s discretion with regard to consummating the relation, is underscored in all of John’s texts, with maybe the Ascent to Mount Carmel and The Dark Night of the Soul being the plenary examples.

Even more, Saint John of the Cross thought that we should not plan for consolations short of union that so many religiously oriented people in the 16th century Spain mistook for the essence of spiritual life. That is, we should not be seekers of special visions, auditions, the charisms of levitation or speech, or become the kind of people to whom the working of miracles is ascribed. All of this drawing attention to the spiritual person as an exceptional individual (the guru complex) misinterprets the spiritual life which is precisely not the life of spectacle, but a life that is out of sight, precisely because it is a life hidden in God. As a faithful Catholic who did not separate himself from those of simple faith, Saint John of the Cross believed that such gifts were possible. Yet he also thought that they were not essential, and he and Teresa worried that with the spiritual seekers of his own day these gifts would be taken for the real thing, and be substituted as idols for the transcendent and loving God who comes in silence. The singular genius of John of the Cross, what makes him our contemporary, is his reflections on a darkness that is neither the “radiant or luminous darkness”—to use the phrase of Pseudo-Dionysius—of union nor the darkness sprinkled with the light of illumination, but rather a darkness in which one does not so much experience the presence of God, but his absence. Here one finds that after all the discipline of taming the senses and imagining, after all the strenuous training of the intellect, and after the exposure of the orientation towards God as the object of our deepest will and love that everything seems to have been for naught: one experiences nothing, is given nothing, not even the promise that this negative experience has an expiration date. Saint John of the Cross is anxious to counter the illuminati, who appear to continually bathe in the presence of the divine to which they have facile access, and to remind the faithful that the spiritual road is long and hard and leads, as Origen thought, through the desert in which images, concepts, and the very prospect of goal appear to be lost. In the desert not only does God have no name, neither does the self. One can find this vintage Origen of desertification more in his Commentary on Numbers than in his Commentary on the Song of Songs. But in any case for both it is of the essence of spiritual life that it will drink the cup of bitterness to the very dregs. Moreover, this view is not in the slightest esoteric: it follows the very pattern of the Cross in which Christ gives up all that he is without the comfort of a divine presence or a reply from the Father. In the gratuitous, representative, and exemplary suffering and death of Christ on the Cross all that is divine is hidden. Spiritual life will necessarily express this emptying of glory, which is an essential feature of love, that is, the giving up of the very aim of love for love’s sake. If this aspect of Saint John of the Cross, which is beautifully articulated in book 1 of the Ascent to Mount Carmel, reminds Christians that their spiritual life is not something that can be segregated from Christ, it is also perhaps the aspect of Saint John of the Cross that has most attracted modern readers on the margins of the Church who truly long for the presence of God in their lives. In Four Quartets T. S. Eliot seems to be speaking to them throughout as he mines the wisdom of Carmel for searchers who have not given up on meaning and truth. The first of the four poems, “Burnt Norton,” reads like a commentary on the Ascent to Mount Carmel or the Dark Night. Part 3 of the poem is about darkness, in principle a negative in that it is a suffering that deprives us of light and divine presence, but also a site and opportunity for purification:

Emptying the sensual with deprivation

Cleansing affection from the temporal (97-98)

And above all curing us of “fancies” (102) and stiffening us in giving us “concentration” (103) that enables us to move beyond “this twittering world” (113). The climax of this borrowing from Saint John of the Cross and the making serviceable of this wisdom for modern man comes a bit later in glorious passage that puts Saint John of the Cross’ quiet meditation of the dark night into a sermonic mode of almost hysterical exhortation:

Descend lower, descend only

Into the world of perpetual solitude,

World not world, but that which is not world,

Internal darkness, deprivation

And destitution of all property,

Desiccation of the world of sense,

Evacuation of the world of fancy,

Inoperancy of the world of spirit;

This is the one way, and the other

Is the same . . .

In the second of the four poems, “East Coker,” Eliot continues to lime John’s reflections on the dark night of the absence of God. Again John’s words are taken on for our most unpropitious and empty time in section 3 of a five-part poem, and thus function as the critical hinge of the poem as a whole. The theme is the dark, or our going into this particular kind of dark, in which our faculties are deranged, our intellectual and volitional competencies negated, and the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love entirely amped down. Eliot speaks first of a silence that is merely a cessation of speech. This is a venial silence, but from it he hopes can sprout a deeper silence at once patient of nothing, that is, holding to the silence that will not get distracted by sense, concept or image. Eliot again transposes the wisdom of the master of spiritual life into a secular sermon and an exhortation:

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without

Love

For love would be love for the wrong thing; yet there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

But if Eliot is interpreting the mystical commentaries of Saint John of the Cross, he is also carrying forward the poetry of Saint John of the Cross which is regarded as one of the peaks of Spanish poetry in the 16th century. Saint John of the Cross is no more a theologian who writes verse than Dante is someone who writes verse who happens to have theological subject matter. And in many ways, Saint John of the Cross is almost, although not quite, as brazen as Dante who is also featured in Four Quartets, especially in “Dry Salvages” and “Little Gidding.” What I mean by this is that Saint John of the Cross does something quite extraordinary when he constructs major texts of spiritual experiment such the Dark Night of the Soul and The Living Flame of Love as interpretations of poems by the same name that he himself writes. Although not in fact, in principle he has made “original” poems the foundation of his theology. This is dangerous as well as extraordinary, since it seems to be granting an authority to poetry that is usually only granted to scripture and the theological tradition. Of course, both of the original poems are rooted in scripture and tradition. The “original” poem the “Dark Night” presupposes the Psalms of the lament and the Gospel accounts of the Cross, and, arguably, the entire mystical tradition which in various ways and degrees speak to moments in which the eros for God slackens and one feels stranded between a leaving of the sensory, imaginative, and conceptual worlds and the real possibility that one will not arrive at a renewed world beyond sense, imagination, and intellect in which we have union with God. The original poem the “Living Flame of Love” clearly bases itself on the Song of Songs, but also the tradition of theological commentary that begins with Origen and which has a high point in the interpretation of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, an interpretation of vibrant physicality that sets the immediate terms for Saint John of the Cross’ poem, which although spiritual holds on to all of eros of spousal union with its longings and deferrals and blissful consummation in which the distinction between lover and beloved is entirely lost.

Saint John of the Cross: Our Contemporary

Let me turn to the Counter-Reformation context within which John of the Cross wrote, and propose the spiritual theology of Saint John of the Cross as one option within a broad vocabulary of Catholic response. One way of responding the Reformation was to bring greater clarity to Catholic theological principles, for example, to deny scripture alone and affirm the prerogatives of scripture, tradition, and magisterial authority and their relation, and also to articulate important doctrines with greater exactitude and comprehensiveness and in particular producing biblical as well as traditional warrants. This was the tack the Catholic Church took in the Council of Trent (1545-63). For example, Trent replied to the Reformers “grace alone” with a far more penetrating theological account of the relation between grace and free will and grace and works than supplied by the somewhat “bumbling” Erasmus in his debate with Luther, however much it may jar us to think of Erasmus as bumbling. Trent also made a theological case for all the seven sacraments, the centrality of the Eucharist, and offered a cogent defense of the real presence of Christ. The kind of response illustrated by Trent was not the only mode of Catholic response. Other ways included making a fresh start with Christianity as a missionary religion and leaving behind a Christianity at once jaded and divided (Francis Xavier). Another way again was to take Christianity seriously in terms of the corporal works of mercy, thereby reminding that Christianity is a practice before it is a theory, albeit a practice that has its center a vision of the figure of Christ who gives away all, even life, to a world in chronic need (Francis de Sales). Finally, another cogent response to the Reformation was to demonstrate the possibility of holy lives by illustrating their reality and drawing a map whereby the seeker would be purified and become a possible object of the grace of God who alone makes holy. In the Reformation personal holiness was denounced both as a theological matter (holy lives are specious forms of religious heroism that distracted from the centrality of Christ) and as practical matter (the attempt to live a holy life inevitably ends in failure): we are riddled by sin and addled by systemic weakness. Like other Christian masters before them, for example, Thomas a Kempis and Tauler, Saint John of the Cross and Theresa of Avila thought that a life of prayer and holiness was possible, even if such a life placed exorbitant demands upon oneself. One could and should funnel all one’s energy into the search for God that was the “real,” but not necessarily fully acknowledged, desire or love in all human life. The main task of the religious life with its discipline of prayer, scripture reading, and reflection is to peel away the many desires and wants that cover over the desire for unconditional love that is primitive, that is our last and first love. John thought himself unoriginal in thinking of this excavation as the one thing necessary to begin the journey towards God marked by risk and vulnerability. The desire or love of God, however, is not autonomous. It is rather a response to the love that God has for us, which if it is generically benevolent, is always particular. God’s love does not disperse and dissipate; I do not get an exhausted droplet of this love. This love, all of it, is given to me particularly as a unique unreplaceable lover and seeker; it is a love that loves me and loves the journey that will make me who I am, a love, moreover, that is infinitely patient of my idling and my falls.

Yet, if the carrying forward of Saint John of the Cross in 20th century poetry is anything to go by, then perhaps Saint John of the Cross can serve also as a reply to the secular focus on immanent satisfaction in comforts, commodities, persons as instruments of satisfaction, and in distraction that then as now we can rely on to sabotage the hard work of the love of God. In any event, in addition to reminding the secular word of the saint as the icon who goes the way of vacuity (“Dry Salvages”), Eliot has a specific reason for putting Saint John of the Cross into play in our secular age. The darkness of the dark night is an opportunity: in order to defeat modern experiences of emptiness it is not sufficient to keep insisting that God is the fullness that cures it. We can suppose this apology and it may even have some measure of success. What Eliot envisions is the prospect of one form of emptiness and silence harrowing and converting another form. More specifically, he imagines the transport of the emptiness and silence of the dark night into the venial silence and speech of our modern world and providing a seed that catalyzes the desire for God, which has been merely temporarily and necessarily suspended, and in which lies the hope or the hope against hope that the self can be released from its arrest. Perhaps we might want to conclude that if it is true that all of John’s poetics of the drama of spiritual life remains valuable in our secular times, Eliot underscores this, maybe this is even more true of John’s stunningly luminous reflections on the darkness in which God appears lost.

I have favored John’s speaking of the dark night over his equally powerful reflections on the experience in darkness of the darkness of God who is superabundant light and the experience in silence of the silence of God which though beyond language says everything the self would hope for. I have done so largely for reasons of how Saint John of the Cross has been received in modern times in which the dark night of the absence of God has been dominant. This is hardly the death of God of which modern theologians pontificate: the dark night of the senses and spirit is a moment (whose duration we cannot measure) in which we experience in agony the absence of a compassionate God who wants to crown our eros with union. Moments of union in this life remain the goal, as permanent union is in the next. No greater union could possibly be thought: it is nothing less than the meaning of this life and the next. Nonetheless, the way forward has ingredient in it the experience of being stranded. This is only relieved by hope or hope against hope, a tensile waiting for the capacity to move on again. Should we once again begin to experience God in some way, this too will be a divine gift. Of course, the experience of the dark night, the experience of the absence of God, is figured by Christ. Saint John of the Cross does not get this ascription for nothing: beyond the mapping of a dramatic spiritual itinerary there is Christ uttering the cry of dereliction: God, God, why has thou forsaken me (eli eli lama sabachthani). This is Mark 15:34 recalling Psalm 22. It might be the case that this is where not only those wanting to believe, but all of us within the Catholic Church, find ourselves at the moment. In a world in which the Church scandals that beset the faithful threaten to extinguish the desire for God, the believer feels stranded and hopeless. We perhaps are more familiar with this hopelessness than we believe. Saint John of the Cross did not only write the “Dark Night,” but also a poem of lament that imitated Psalm 136, “By the Waters of Babylon.” Here are some of the lines in which the poem presses towards a strangled form of hope:

By the waters of Babylon

I sat down and wept,

And my tears

Watered the ground,I took off my holiday robes,

Put on working clothes,

And hung my harp

on a green willow,laying it there in hope

of the hope I had in you.

There love wounded me

And took away my heart.

Lament is the communal correlative of the dark night of the soul whose register is individual. Still neither lament nor the dark night of the absence of God is for Saint John of the Cross the last word, even if we have to abide for a time with lament and the dark night in which God is silent in absence, and our circumstance does not yield the divine gracious silence of the triune God that surpasses everything. But make no mistake the goal remains union with this God who is dark only because of the excess of light and fire and of a holiness that makes us holy. This making holy will continue in this our communal dark night: saints are a sign; and if Eliot is right, perhaps for the moment the necessary and only sign. They are icons of Christ and the Cross, icons of Christ on the Cross.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay was originally delivered as a Saturdays with the Saints lecture entitled “Saint John of the Cross: Silences and the Spiritual Life” on 1 September 2018. Please take a look at the past Saturdays with the Saints schedule here.