The human condition is not pain only.

Yet pain rules us and has much power.

Wise thoughts fail in its presence.

Starry skies go out.[1]

The sense of touch is the building block of the five senses. The largest internal organ in humans might be the liver, but the conduit of touch, the skin, dominates overall. Touch is the basis for how we commune with the world. The Incarnation also means that Christians believe God touches us directly, especially in the Eucharist.

As you read this piece you are either touching your keyboard or device screen. You are absorbing the rest through other senses that rely upon touch. The priority of touch is encoded in idiomatic phrases such as, “This is touching,” or, “That touched me.” They denote a profound encounter that touches the whole person (the Biblical heart), that is, mind, body, and soul.

Touch is so ever-present and inescapable, because it both opens us to the world and (one might say “therefore”) vulnerable to the world and dependent upon it. The constant intrusions of the outside world upon our exposed skin, occasionally painfully wounding, remind us that we are not the center of the universe, and definitely not ensconced within its command center.

Yet, paradoxically, healing does not issue from avoiding touch and ignoring pain. We did not need neuropsychologists to tell us that infants will not thrive without touch and that it is likely they will die without it. We speak of people who are unmoored from life as being “out of touch” with their world. Not surprisingly, the only way to heal our wounds is to humbly acknowledge our dependence and gingerly get back in touch with the world and its Creator. This is why the sense-deprivation of solitary confinement is the most inhuman form of imprisonment and an analogue for hell.

The 2018 New York Encounter, an annual conference hosted by the Communion and Liberation ecclesial movement,[2] was the incubator for the metaphysics of the above reflections. The Encounter is a three-day carnival of lectures, conversations, and readings. The event is animated by a charism for making connections between the neuralgic points between the secular and the sacred. This year’s gathering included the usual mix of respected established thinkers (sociologist Amitai Etzioni,[3] political scientist Mark Lilla, poet Ed Hirsch), relative unknowns (who shall remain unnamed), and a dizzying array of sessions about Dorothy Day, poetry, economics, Terrence Malick's films, political extremism, and medicine. In between were lunches, museum visits, making new friends, and discussions with Communion and Liberation friends from all over the States.

There was such a natural rhythm between the official sessions and the personal encounters that it was impossible to posit where “serious” serious study was being done and where you were hanging out with folks you know. Sometimes the presenters were friends. At other times they became friends. The whole seamless three-day spectacle made you question standardized education requires the mind and heart to be disjointed, when we need both to be fully in touch with reality, because, at the most basic level, mind and heart only work in tandem. Pure experience without mind is merely a rush of unprocessed impressions to the head. Pure mind without experience is the definition of schizophrenia.

To my surprise the most fascinating session of the conference was the one on medicine—a topic I usually have as much interest in as I do for going to the dentist to get my teeth pulled. This was supposed to be my nap time, but surgeon Michael Brescia talked about inventing a billion dollar procedure, getting talked out of monetizing it by his pious his blue-collar father, using the fame from the invention to get the palliative care Calvary Hospital certified, and, down the road, getting an assisted suicide bill thrown out in New York state.

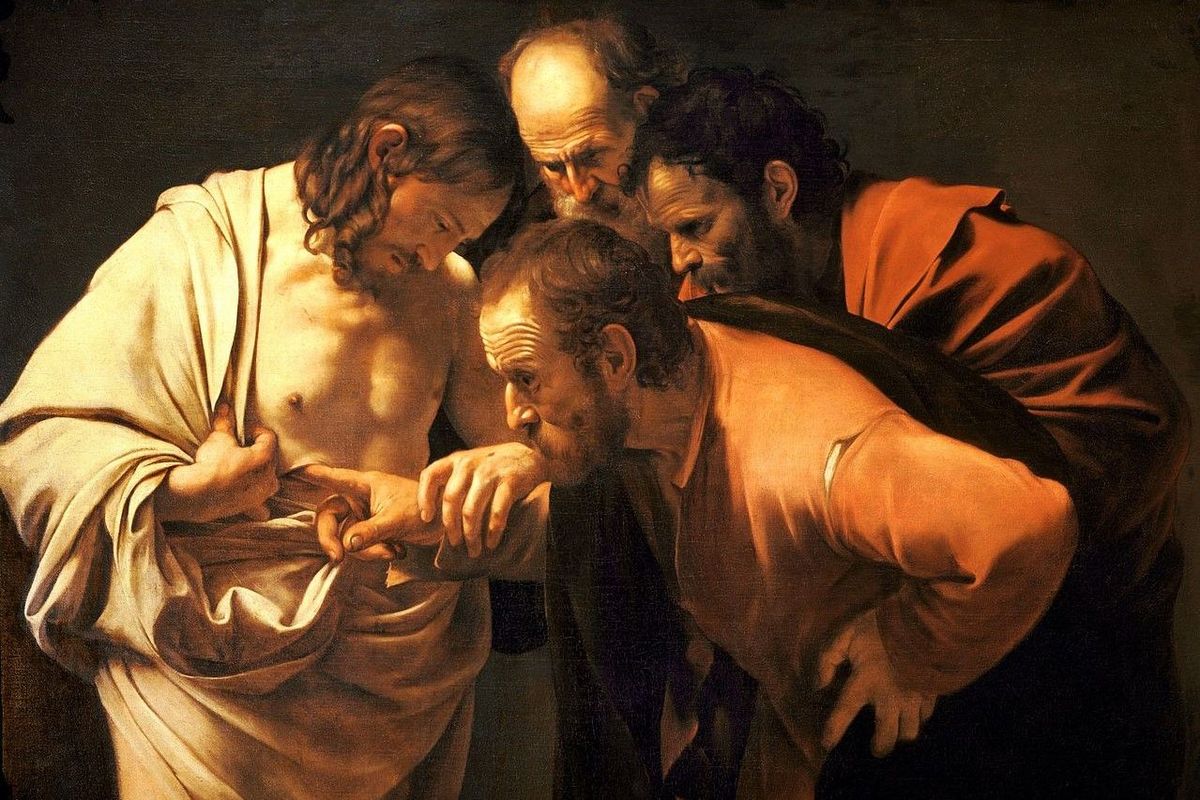

Why did it move me so? Because all of Dr. Brescia work, as secular as some of it looks, is imbued by a profound faith in both the Wounded Healer and of Christ in even the most miserably aggravated pain-stricken patient—some of them shouting in their agony. Dr. Brescia reminded us that Christ was resurrected with his wounds, which he offered to Doubting Thomas to touch.

The healing power of touch is at the center of the Calvary Hospital revolution in palliative care and what ultimately doomed assisted suicide in New York. Doctors and nurses at Calvary are asked to form close bonds with their deeply-suffering patients who are never restrained in any way. They are encouraged to touch patients with care, to treat them like human beings of infinite value, once trust is established. These caretakers are instructed to always remember that the human condition is not pain only, because, even if sometimes pain rules us and has much power, there nonetheless remains an ineradicable metaphysical core of human dignity to every person. That core can be touched and healed even in cases where extreme pain does not go away and Kant's starry skies seem distant.

[1] Czeslaw Milosz, “Body,” in Selected Poems (Krakow: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1996),

[2] See: Sofia Carozza’s interview about What is Communion and Liberation? on the digital pages of Church Life Journal.

[3] Whose book Happiness is the Wrong Metric (New York: Springer, 2018), true to his communitarian philosophy (an inspiration for Catholic thinkers such as Patrick Deneen and Charles Taylor), is now available online for free, open-source.