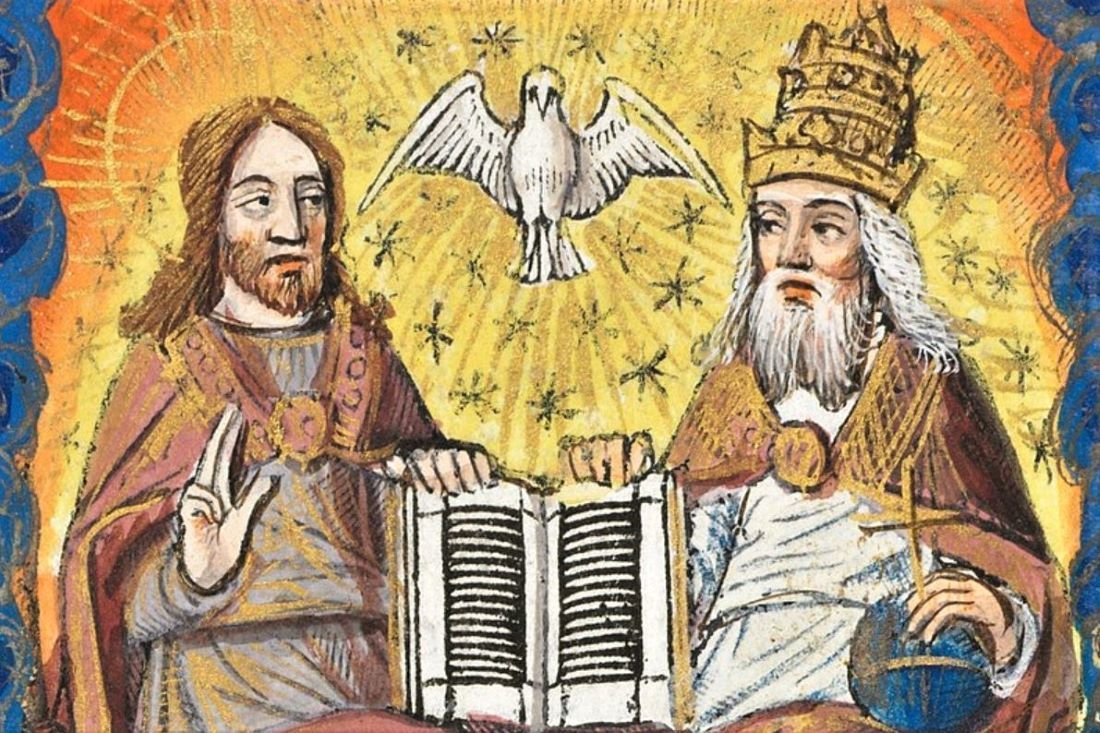

Scripture does not bear witness to itself but instead to God. The divine res of Scripture are its true end and purpose. The language of Scripture does mediate historical and doctrinal truths. The reality to which Scripture refers, though, is not a set of discrete, logically or conceptually related propositions of doctrine. The reality to which Scripture refers is the recapitulation of all things in Jesus Christ in the history that is. Every teaching and doctrine of Christian faith has this reality as its referent. This reality is a divine mystery. It is the gift of God’s self to humanity through the cross of Christ and sending of the Holy Spirit. “It is already a first abstraction,” writes de Lubac,

. . . to separate completely the gift and the revelation of the gift, the redemptive action and the knowledge of redemption, the mystery as act and the mystery as proposed to faith. It is a second abstraction to separate from this total revelation . . . certain particular truths, enunciated in separate propositions, which will concern respectively the Trinity, the incarnate Word, baptism, grace, and so on.[1]

De Lubac states that such abstractions are necessary given the constitution of our created minds. We cannot help but naturally raise questions. We cannot help but understand the unity of the work of an infinite God through our finite and discursive minds. We must, however, take care to remember that:

In Jesus Christ all has been both given and revealed to us at one stroke; and that, in consequence, all the explanations to come, whatever might be their tenor and whatever might be their mode, will never be anything but coins in more distinct parts of a treasure already possessed in its entirety; that all was already really, actually contained in a higher state of awareness and not only in ”principles” and ”premises.”[2]

What the Triune God proposes to us through Scripture has intelligible content, but the good news of the redemptive work of the Triune God is more fundamentally a call to us. The entry of divine meaning into human history in the person of Jesus Christ and the mission of the Holy Spirit requires a response. The Holy Scriptures, after all, are able to instruct us for faith in Jesus Christ (2 Tim 3:15). At Pentecost, Luke testifies that Peter preached the message of the crucifixion and resurrection of the Lord of Glory, foretold by the prophets, which was fulfilled in their own time. The people were cut to the heart and responded in faith (see Acts 2:14–42). That is the appropriate response to the work of the Holy Spirit in the exposition of Scripture. Engagement with Scripture is a means through which God addresses and so transforms us.

Revelation, in fact, is at the same time a call: the call to the Kingdom, which is not open to men without a “conversion,” . . . an inner transformation and, as it were, a recasting not only of will but of being itself. Then the entrance into another existence is produced. It is a new creation, which resounds in one’s entire awareness: it upsets the original equilibrium, it modifies the orientation of it, it opens up unsuspected depths in it. Eyes open anew on a new world. The community of life allows the giving of new meaning, its whole meaning to the divine object of faith.[3]

The ultimate end of Scripture, in the missions of the Son of God and Holy Spirit in history, is the ongoing processes of conversion in those who engage it. The study of Scripture provides a means through which Christians can be “transformed by the renewing of [their] minds, so that [they] may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect” (Rom 12:2).

Scripture does not merely mediate judgments about things that have taken place in the past or about the doctrinal truths of Christianity. That is only part of its purpose. Scripture, like all literature, is an invitation to encounter. “Literature,” writes John Topel, “invites the reader into its world and asks for a commitment to that world. In so doing, it works the transformation of the reader’s experience, imagination, understanding, and action.”[4] Scripture is a privileged literature for the Christian community because Christians have historically discerned the Triune God calling them through it towards Godself. De Lubac explains, “All that Scripture recounts has indeed happened in history, but the account that is given does not contain the whole purpose of Scripture in itself. This purpose still needs to be accomplished and is actually accomplished in us each day.”[5] “Exegesis is a kind of ‘exercise,’” he writes elsewhere, “through which the believer’s mind progresses.”[6] Christian engagement with Scripture facilitates the Holy Spirit’s work of transforming the believer spiritually, morally, and intellectually, conforming her to the likeness and form of Jesus Christ who reveals the Father through the Holy Spirit.

The ultimate telos of engagement with Scripture is encounter with the transcendent God who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Such an encounter reorients the horizons of the reading and hearing communities of Scripture towards transcendent values. Those in Christ set their minds on “heavenly things” (see Col 3:1–4, 12–17). “For the Spirit,” Paul writes elsewhere, “searches everything, even the depths of God” (1 Cor 2:10). The indwelling of the Holy Spirit radically reorients Christians’ focus and direction towards the transcendent Lord of the universe. I described this momentous transformation in chapter 4 of Divine Scripture in Human Understanding as religious conversion. It is the reception of the love of God flooding our hearts (Rom 5:5), so that we are able to return that love to God with “all of our heart, soul, strength, and mind” (Mark 12:30). Christians return to the texts of Scripture again and again to be “trained in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16), which is the very righteousness of the Triune God.

But the love of God that floods the hearts of Christian believers entails a love of all that God has created. It is impossible to love with God’s love if one does not love all that God loves (1 John 4:7–12). The dual end or purpose of Scripture, the finis of the law of God (Rom 13.8; 1 Tim 1.5), is this love of God and neighbor (Matt 22.37–40). “So if it seems to you that you have understood the divine Scriptures, or any part of them,” Augustine declares, “in such a way that by this understanding you do not build up this twin love of God and neighbor, then you have not yet understood them” (Doctr. chr. 1.26.40). The purpose of reading, studying, meditating upon, remembering, and hearing Scripture is this ongoing divine work in the Christian believer. It is impossible to understand Scripture in any adequate measure if the reader stops short of these divine intentions. Scripture has as its purpose the transformation not only of our minds, but of our wills; such transformation entails new possibilities for new action in the world. God frees us to love all who God loves and all that God loves. And we act in accordance with that change.

“The Christian gospel is an invitation to metanoia, to change,” writes M. Shawn Copeland, “the standard against which that change is measured is the life of Jesus Christ.”[7] The experience of the Holy Spirit’s work conforms the Christian believer to the form of Christ through giving her the mind of Christ. That divine work transforms readers so they are able, like God, to love even their enemies (Rom 5:10). Engagement with Scripture is a means of grace-oriented towards that end. Scripture, as inspired by and used instrumentally by the Holy Spirit, represents an especially apt resource for the Christian believer’s growth in the fruit of the Spirit, “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, gentleness, faithfulness, and self-control” (Gal 5:22).

Even the stumbling blocks of the history of Scripture have roles in the transformative pedagogy of the Triune God. Critical biblical scholars, for all of their tremendous work, must recognize in humility the historical gaps in our knowledge of the ancient worlds in which Scripture was first written and transmitted. The recognition that Scripture, though written through the movement of the Holy Spirit, has nevertheless—and necessarily—been mediated in human language and by human hands, minds, lips, and ears throughout Christian history requires a measure of humility in all Christians; we must admit both our dependence upon faith in the providence and wisdom of the Triune God for acting in such ways and our dependence upon the countless believers—and even scholars—who have handed on these texts before us so that we could possess and read and hear Scripture today.

As they return to the Sacred Page again and again the Spirit conforms those who read to the image of Jesus Christ. The transforming work of the Triune God in Christian believers through Scripture thus entails ongoing moral transformation. The processes of reading, hearing, studying, meditating upon, memorizing, and reciting Scripture reorient believers towards God, and that reorientation transforms their priorities and values to align with the priorities and values that God reveals are God’s own.

Engagement with Scripture can also induce changes in the philosophical horizons of those who study it. The achievement of being able to recognize the plurality of human perspectives in Scripture can be an invitation for one to take responsibility for one’s own perspective. That achievement can help one to reflect on why and how the language of Scripture and the realities attested in Scripture should have a place in informing one’s own perspective. Recognition of the historical distance between the world(s) of Scripture and the contemporary world can be an invitation for readers to make explicit an awareness of the historicity of human language and culture. The modern discipline of historical scholarship is built upon the recognition and thematization of historical consciousness.

Historians, including those whose life work involves the study of the texts of the Christian Bible, operate within a scholarly differentiation of consciousness through which they are able to selectively study and hypothesize about social, cultural, and religious developments in the past. Because of the legitimacy of such questions and answers about the past, McEvenue notes, “the rejection of scholarship cannot be tolerated once scholarship has become a cultural possibility.”[8] Biblical scholarship cannot be ignored because it raises, and sometimes answers, actual authentic questions about the origins and intelligibility of the Christian scriptures as the human artifacts that they are. “The questions remain important and valid,” Young writes, “even if we are unsure of the answers.”[9] The exigencies of attentiveness, intelligence, reasonableness, and responsibility require that such questions be asked and answered to the best of our abilities. But questions about the historical particularity of the authors, audiences, and cultures of Christian Scripture are not the only questions we can ask about the text. In fact, authentic engagement with Christian Scripture is a divine means through which further questions of commitment and response occur in and to readers, hearers, and interpreters of these texts.

The recognition that those who engage Scripture, both historically and in the present, employ diverse culturally conditioned forms of reasoning in order to make sense of it can serve to help one become aware of the ways in which one’s own education, family histories, political allegiances, and faith traditions have formed one’s own questions. The fact that reading always takes place in cultural circumstances, coupled with the judgment that the Triune God addresses or intends to address and speak to all people in all cultures, requires the concomitant judgment that authentic readings are possible precisely from and within the particularity of specific cultures.[10]

The work of sorting out faithful and responsible interpretations that reflect and promote the redemptive economic work of the Triune God and those that oppose it remains an ongoing task for the global and historical body of Christ. The recognition of the differences in the kinds of language that are employed in Scripture, in the creeds, and in systematic theology, respectively, can serve as an invitation for individuals to consider the possibilities that the specialization of languages provides for understanding and making judgments about divine and created being and for expressing those judgments in forms of commonsense language, the specifications of technical language, and symbolic and artistic representations.

In each of these ways, engagement with Scripture can facilitate a process of self-appropriation, whereby readers recognize what it is that they know about and through Scripture, how and why that knowledge is actually knowledge, and, finally, what it is that they know when they are in possession of that knowledge. It is not possible to approach Scripture from nowhere, but it is not necessary for readers to remain in ignorance of where they stand when they are engaging it. “Everybody has his filter,” writes de Lubac,

. . . which he takes about with him, through which, from the indefinite mass of facts, he gathers in those suited to confirm his prejudices. And the same fact again, passing through different filters, is revealed in different aspects, so as to confirm the most diverse opinions. It has always been so, it always will be so in this world. Rare, very rare are those who check their filter.[11]

Authentic engagement with Scripture can provoke readers and hearers to check their filters and so serves as a performative means of spiritual, moral, and philosophical renewal. Scripture is thus an apt instrument for enabling its readers to undergo religious, moral, and intellectual conversion. While concrete history demonstrates that such conversions do not automatically or of necessity follow from engagement with Scripture, Scripture both reflects the influence of such conversions and, when engaged authentically, leads to such conversions. The kinds of attention, intelligence, critical reflection, and deliberation that Scripture requires of its readers and hearers impel individual and communal readers towards the self-transcendence that is both natural to them as human beings and is supernaturally possible for them through the grace of God healing and elevating their whole selves.

Christian Scripture is an instrument of the Holy Spirit and Son of God, and its purpose is to facilitate the transformation of its readers for their participation in the recapitulation of all things in Christ. It is the Holy Spirit’s broad, historically multifaceted work in inspiring Scripture—in the loci of its authors, the worlds it projects, and its interpreting communities—that has affected and will continue to affect the manifestation and actualization of the work of the Son in history. As Paul writes, “No one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except by the Holy Spirit” (1 Cor 12:3b). The Christian Church, the Body of Christ, participates in this work through the continuing missions of the Son and Holy Spirit in history. The Church takes up and reads Scripture again and again to discern the will of God, to be convicted of the sins of her members, and grow “to maturity, to the measure of the full stature of Christ” (Eph 4:13b).

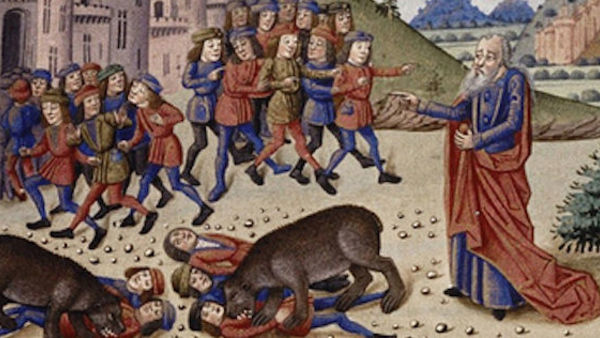

Christian Scripture is a potentially dangerous instrument, however. Because Christian believers recognize it as an instrument of the Triune God, it possesses a profound symbolic authority.[12] And some readers and hearers have mistakenly construed its authority in demonic and idolatrous ways. Scripture has proven itself useful as an instrument for the work of the Triune God in history, but it has tragically also proven to be a useful instrument of violence and oppression.[13] To use Scripture in the latter way, however, is to reject the authority of the Son of God Incarnate, Jesus Christ, to whom Scripture testifies. The authority that Jesus Christ exercises in his incarnation, life, teaching, death, resurrection, ascension, and lordship over all of creation is self-sacrificial; it is kenotic.[14] Jesus declared to his disciples,

You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. Whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave; just as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many (Matt 20:25–26).

Paul writes that Christians should have the same mind-set:

That was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross (Phil 2.6–11).

The humility of Christ is the measure of all exercises of human authority, including those that appeal to and utilize Christian Scripture. Those who utilize Christian Scripture authoritatively must take caution; for Christ testifies that everyone will give an account for every careless word uttered (Matt 12:36; see also Rom 14:10–12). Given the high responsibility of speaking for the Triune God, James cautions that not many should become teachers, because those who do will be judged more harshly (Jas 3:1).

As a textual and linguistic artifact, Christian Scripture does not impose itself on readers in ipse because it is not an agent. “The Word of God,” on the other hand, “is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing until it divides soul from spirit, joints from marrow; it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Heb 4:12). The written Word of God mediates this living Word of God in the processes of attentive, intelligent, reasonable, responsible, and faithful Christian use and interpretation of Scripture. A Christian reading of Scripture thus requires a posture of openness and vulnerability. Scripture is useful for correction and rebuke (2 Tim 3:16).

The Christian reader must be self-critical above all else. Christian reading requires one to have experienced the Holy Spirit’s internal work, refashioning the inner person in conformity with Christ. It requires one to have an openness to mystery, to transcendence, to perplexity, and to suffering. To participate in the economic work of the Triune God, one must lay down any desire to control God or God’s authority. One must become as Christ. It is possible to read Scripture in willful ignorance and blindness, utilizing it to promote our selfish desires. To turn Scripture from its purpose towards such selfish ends, though, is to reject an invaluable treasure and to shirk the authority of the Triune God to whom it bears witness. Those trained for the kingdom of heaven, however, are able to draw out of this treasure “what is new and what is old” (Matt 13.52b).

EDITORIAL NOTE: This excerpt comes from the book Divine Scripture in Human Understanding: A Systematic Theology of the Christian Bible (pages 252-260) by Joseph K. Gordon. It is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. You can read our excerpts from this collaboration here.

[1] Henri de Lubac, “The Problem of the Development of Dogma,” 274.

[2] Ibid., 275.

[3] Ibid., 275.

[4] Topel, “Faith, Exegesis, and Theology,” 342. So also Boersma: “As we read Scripture, we come to understand ourselves in the process—and, of course, vice versa: as we come to understand ourselves better, we become better equipped to read Scripture.” Boersma, Scripture as Real Presence, 114.

[5] De Lubac, Medieval Exegesis, 1:227.

[6] “L’exégèse est de la sorte un ‘exercice’, grâce auquel l’esprit du croyant progresse.” Ibid., 2.2:86; translation mine.

[7] Copeland, Enfleshing Freedom, 6.

[8] McEvenue, Interpreting the Pentateuch, 28. For two apologies for this judgment, see Fitzmyer, The Interpretation of Scripture; Harrisville, Pandora’s Box Opened.

[9] Young, Virtuoso Theology, 18.

[10] This compact judgment reflects my assent to the legitimacy of “so-called” contextual reading strategies (all reading, after all, is contextual). But such reading strategies find their own legitimate place within the historic Christian community’s discernment of the actual redemptive and transformative work of the Triune God in history.

[11] De Lubac, Paradoxes of Faith, 102.

[12] For discussion of the “status” authority of Scripture, see: Cosgrove, Appealing to Scripture, 9–11.

[13] See Siebert, The Violence of Scripture; and the works listed in its bibliography.

[14] For a brilliant discussion of the kenotic dimensions of Christ’s lordship, see Copeland, Enfleshing Freedom, 63–65.