We rightly approach Scripture with reverence and a certain solemn spiritual hunger. Therefore, we do not often think of these inspired texts as having any sort of humor or laughter in them. This is especially true if we are Fundamentalists, or, take every word of the Bible literally.

Nonetheless, there are a number of Scripture passages that make me pause every time I hear or read them. These are in the Bible itself. They are not just the result of insufficient preparation on the part of the lector in regard to a particular text. One passage in particular comes to mind as an example of the latter: Luke 2:16. The text may say, “The shepherds went in haste to Bethlehem and found Mary and Joseph, and the baby lying in the manger,” but the lector almost always proclaims instead that they “found Mary and Joseph and the baby, lying in the manger.” I will leave to your imagination how the “flaming brazier” of Genesis 15:17 comes across from some lectors.

What I am considering is something rather different. The Bible has a special status as the Word of God, but it is also quite simply literature and needs to be considered, at least at times, in that light if we wish to properly understand the manner in which each author wrote. Reflect on the fact that Shakespeare himself would include humor even in tragedies like Hamlet or Macbeth, and you will not be surprised to raise an eyebrow (or the corners of your lips) when you encounter certain biblical passages.

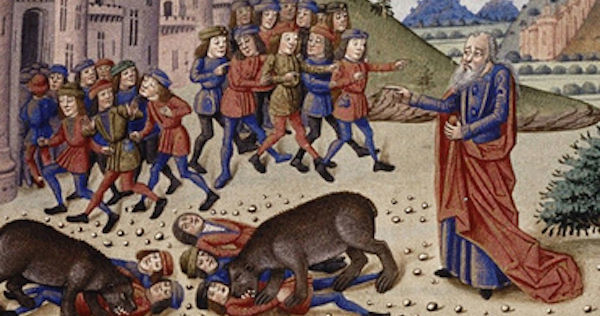

Elijah, for example, has a fine old time in his contest with the priests of Baal in 1 Kings 18:20-39. Their frustration and his mockery is definitely funny all by itself. Some young men mock old Elisha for his baldness in 2 Kings 2:23-24, and the prophet gets his curmudgeonly revenge with the help of 2 hungry bears. This anecdote is funny in modern eyes, partially because the young men mock his baldness, partially because of the brevity of the story, in part for the “instant karma” involved, and in part because the antagonists are sometimes identified as “boys.” One scholarly interpretation suggests that this is a story of Elisha's ability to call down death juxtaposed with a tale of how he could also give life, while another interpreter proposes that these “young men” were prophets supporting a rival shrine at Bethel and were mocking Elisha on that basis. I doubt that the Israelites would have seen any humor in these verses, but to modern ears they cry out for at least a chuckle.

Matthew 8:34 (Mark 5:16-17; Luke 8:37) has the villagers unhappy when Jesus drives the demons out of the man who lived among the tombs. At the demons' request, Jesus sends the demons into a herd of swine, who then commit suicide in the Sea of Galilee. The pagan villagers do not see the significance of the miracle, and I can understand their dismay over their rather severe economic loss, even if it is a matter of “unclean” swine. I can also comprehend their anxiety over what Jesus might do next, but there is still something humorous here in their panicked response.

When Zechariah returns home after his vision in the Temple (Luke 1:62), his friends and relations make signs at him as they try to discover what name he wishes for his son. Zechariah is not deaf but dumb, and yet the people make signs at him instead of speaking?

Mark 3:16-17 lists rather formally the names of the apostles: “And so He appointed the Twelve: Simon, to whom he gave the name Peter, James the son of Zebedee and John the brother of James, to whom he gave the name Boanerges or 'Sons of Thunder' . . . ” Can you just picture Jesus actually calling them that? There is a reason for that nickname, though, as in their fervor they are unhappy with a man using Jesus's name to heal the sick and they zealously try to stop him (Mark 9:38-40; Luke 9:38-39). They show the same zeal in a passage which soon follows in Luke (9:53-56), where the brothers want to call down fire upon a Samaritan village for refusing to welcome Jesus. There is a certain innocence about the directness of their apparently youthful response, but the very idea of Jesus hanging such a nickname on them, one rooted well-enough in reality to appear in Scripture, puts Christ in a much more human light than the austere, thoughtful, driven, combative, instructive, and empathetic Christ who dominates the Synoptics and our own concepts of the Lord.

I have a strong sense that Jesus is teaching these men by teasing them, and I see something akin to that in the exchanges that Jesus has with some other people, especially with the Samaritan Woman (John 4:1-42) and with the Syrophoenician woman (Mark 7:24-30; Matthew 15:21-28). Why only women? Because they would respond better than men to the respect and love that good teasing can imply?

The case of the Man Born Blind (John 9:1-41) is different. We see a carefully calculated theological argument in the man's sarcastic response to the Pharisees (vv. 24-34), a response that can raise in us a warm appreciation of his sly wit, a response beautifully balanced by the humble words he then offers to Jesus (vv. 35-38). This blind man sees further than the experts and has the courage to respond in faith and understanding.

Acts 14:11-15 shows how the healing of a cripple leads to the consternation of Barnabas and Paul as they suddenly find themselves worshiped as Zeus and Hermes. The scene most definitely reminds me of the hilarious witch's trial at the beginning of Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Do we get a sense here of a God who can be simply affectionate and playful at times?

Should we then consider the story of Jesus in the Temple when He was 12 years old? In a rather serious vein, we do see what is going on here (Luke 2:41-51) with the adumbration of his mission (which he will actually commence about as far from the Temple as he can get, and in a very “non-liturgical” form), but I still see how the Perfect Man is acting like a Perfect Teenager as he walks away from his parents without saying goodbye and then gives his Mother lip when she asks what he thought he was doing. And it would seem like he was grounded until he learned his lesson: he returned home with them and grew in age and wisdom and grace (or, in a more literal translation, the NRSV): “Jesus increased in wisdom and in years, and in divine and human favor” (Luke 2:52). But you need a special sort of mind to see the humorous in this, which really isn't that funny, right?

And I'm not even mentioning the entire book of Jonah, from start to finish a satire of our human pettiness and our resistant response to God's passion to bring us to life.

Humor is often the result of two “readings” of a text or a situation which are in some sort of conflict. This conflict can affect us in a positive and light-hearted way, or, can even be instructive. As I see it, the humor in these passages I cite is not simply for the sake of laughter but can be an educational tool or a revelation of some sort (as in showing us the affection of Jesus when he teases those he loves). The authors handle their material in a unique manner in each passage, and the results are as individual as the style of any really good comic.

What do we get from this, and what difference does it all make? That is always the question.

Maybe it opens a means for us to enter more completely into biblical passages to test for what each one says or can say to us; it might also be a means to let the passage enter into us, to make every aspect of a passage available to us, not simply the humorous, so that it can change us. Both directions of that opening to the Bible are actually aspects of that same listening and truly hearing God's word to us. A readiness to hear a passage in depth, free at least in part of our previous understandings and insights, is a true openness to God's word.

That answer is far from satisfactory to me. I see the humor and I feel a certain joy in reading such passages, but as for what value does it have? I think that I shall have to wait until I am older and hopefully wiser to find a satisfying explanation for this aspect of Holy Writ.