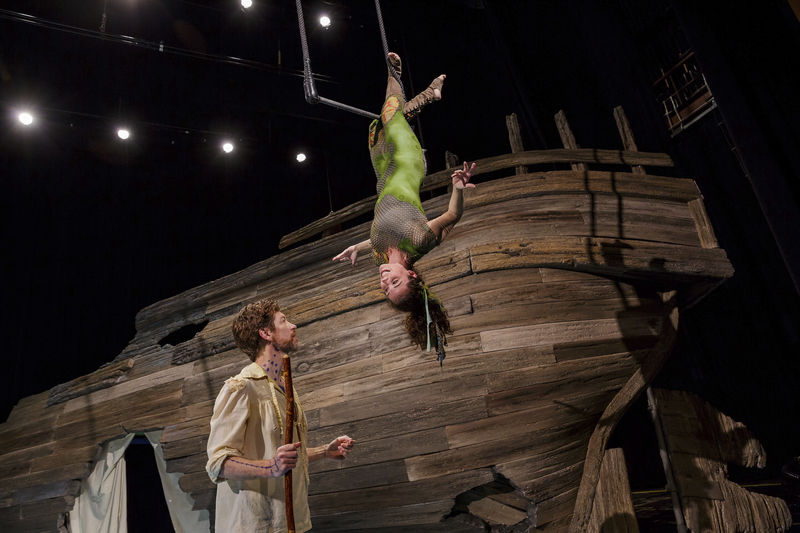

Over the last several weeks, the Notre Dame Shakespeare Festival put on a visually stimulating and highly comedic production of The Tempest. While the acrobatic feats of Ariel (who was hanging from a trapeze the entire production) captured the eye, it was the relationship between Prospero and Ariel that deserves our attention.

The Tempest takes up themes found throughout Shakespeare's corpus. Prospero, the erstwhile Duke of Milan, has been shipwrecked upon an island with his daughter Miranda through the plotting of his brother Antonio and the king of Naples, Alonso. Prospero, a student of the liberal arts, is also a powerful user of magic. Yet, his power is dependent on Ariel, a spirit who is enslaved to Prospero (after he has rescued Ariel from the power of the witch Sycorax).

The action of The Tempest pertains to Prospero's opportunity to avenge himself against both Antonio and Alonso. Prospero causes a tempest that results in the shipwreck of Antonio and Alonso's boat (with a number of other characters in the mix), separating the traveling party from one another. After stopping a poorly conceived plot by the comic troop that would lead to his own murder, Prospero begins to enact his own revenge against Alonso and Antonio. But in the end, he doesn't. He forgives. And he releases Ariel, bestowing the gift of freedom.

Why does he forgive? The Tempest suggests that there is a love between Prospero and Ariel that eventually converts the former toward the act of forgiveness. Ariel's relationship with Prospero in the play is necessarily marked by her identity as Prospero's slave. She must obey. But she wants more than this master-slave relationship. She wants to be loved:

Ariel: Before you can say 'Come' and 'Go',/And breathe twice, and cry 'So, so',/Each one tripping on his toe/Will be here with mop and mow/Do you love me, master? No? (4.1.44-48).

The production at Notre Dame played upon this desire for Ariel to be loved. Prospero, played by a younger man, develops chemistry with Ariel, herself a young actress, throughout the play. In this production, as Ariel hung from a trapeze, she alone could perceive every moment of the story. She is everywhere. And she can knows better than anyone else her master, Prospero. She loves him. The actress playing Ariel made this visible on her very face, manifesting to the audience again and again an unmet eros.

Yet, Prospero for his part cannot return this gift of love until the very conclusion of the play. As he prepare to enact his final revenge, it is Ariel's voice who interrupts:

Ariel: ...Your charm so strong works 'em/That if you now beheld them your affections/Would become tenderProspero: Dost thou think so, spirit?

Ariel: Mine would, sir, were I human.

Prospero: And mine shall/...The rarer action is/in virtue than in vengeance.

It is Ariel's very love that makes possible Prospero's forgiveness, his return to the fullness of his humanity. In her love for him, for his humanity that she alone can fully perceive, Ariel becomes the protagonist of forgiveness. Prospero, through this love that comes as total gift, completes Ariel's lines. Ariel's love converts, opening up Prospero to the value of "virtue" above vengeance. The ease through which Prospero forgives is not itself the result of magic. It is instead the power of Ariel's love, which was forming Prospero throughout the play, that makes possible a return gift of love upon the part of Prospero.

In this sense, perhaps The Tempest is actually Shakespeare's greatest love story. It reveals a love, which cannot be consummated (for a spirit cannot unite with body), that nonetheless makes possible the "comedy" of The Tempest. It is a love that opens up Prospero to a world of values, which only slowly (throughout the play) become his own. Such love ironically is offered by a non-human character, who nonetheless humanizes the protagonist.

The genius of Shakespeare's comedies (and The Tempest is at least kind of one of these) for the Christian is that it opens us up to the manner in which love humanizes the world. It manifests to us in dramatic form what happens when a kind of "divine" love leads to conversion.

Dietrich von Hildebrand, writing on this aspect of love, writes:

When a person loves—and this is once again eminently the case with spousal love—he discovers a whole new world of goodness; he becomes alert to an aspect of the world that had before not intuitively revealed itself to him, he becomes alert to a new dimension of beauty and depth in the universe…In love I awaken to a deeper view of all values and to a new and deeper relationship to them...(The Nature of Love, 77).

It is the power of love itself that allows us to dwell in a meaningful universe. And only in this kind of world is it possible to offer the mercy of forgiveness. To offer a return gift of love in response to the love first received.