George Steiner made the controversy over whether one prefers Tolstoy or Dostoevsky famous in his 1959 book by that title. The idea may have been sparked by a 1953 essay by Isaiah Berlin, where he posited a divide in great literature between hedgehogs (who see the world through one great idea—Plato, Dante, Dostoevsky) and foxes, who create panoramas of human experience (Aristotle, Shakespeare, and maybe Tolstoy?). Berlin was playing an “intellectual game,” by his own admission, but Steiner dug deeper into the possible delineation between these two particularly mammoth thinkers and artists. He proved true the Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev’s claim that “two patterns, two types [exist] among men’s souls, the one inclined toward the spirit of Tolstoy, the other toward that of Dostoevsky.”[1] For Steiner, this pattern divides between the epic storytellers and dramatic tragedians, exemplified by Tolstoy versus Dostoevsky. While Berlin could not quite decide whether Tolstoy belonged in the camp of hedgehog or fox, with Steiner’s lines in the sand drawn, let me classify Tolstoy as fox extraordinaire.

When David Bentley Hart weighed in on the question, he reframed Steiner’s either/or as a both/and “Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (And Christ).” Despite his suggestion that the Church needs to be reading both writers, he decries Dostoevsky’s art while he uplifts his meaning. Dostoevsky had one overriding objective: throw every reader down before the blood of the Cross and the humiliation of the God-Man tortured there. If we could not face our guilt at the Crucifixion, we had no hope of understanding the extravagant grace of resurrection. All of his fiction aims at the Incarnation, even if his art does not meet worldly standards. From Hart’s assessment, in contrast with Dostoevsky, Tolstoy rises higher as an aesthetic master, though he “was practically a liberal Protestant, who thought Jesus principally as a divinely inspired teacher of moral truth: he was not only indifferent to, but scornful of dogmatic tradition.” Yet, Tolstoy should be praised for his realism, his depth of insight into the morals and manners of people. In spite of his loosey-goosey theology, Tolstoy is justified by the psychological depth of his humanizing art.

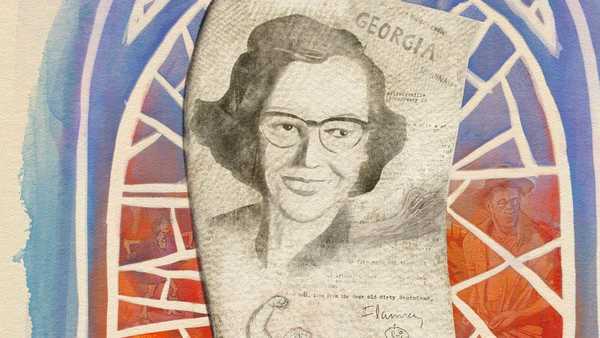

I want to begin to understand two markedly different American Christians authors within this framework: Marilynne Robinson and Flannery O’Connor. Could it be that the controversy between Tolstoy and Dostoevsky might shine a light on the division between these two writers? I probably feel about Robinson how she feels towards O’Connor: she describes O’Connor as a beautiful prose writer with an appalling imagination.[2] Although I teach Gilead regularly and can acknowledge the superb talents of Marilynne Robinson as a novelist, I would rather read a Flannery O’Connor story. Because of my penchant for O’Connor, I have read much more of her than I have of Robinson. As I publicly admitted, I have read a dozen or so of Robinson’s essays, articles on her, but for her other novels, only bits of Home and Lila. Now that readers have the fourth novel in the series, Jack, is there anything new we can say about Robinson and O’Connor?

On Jack

Robinson set the first of the Gilead series in a sundown town by that name, where the “white Christian failure,” as one reviewer puts it,[3] hovers on the edge or out of sight of the main character John Ames, who prefers to ignore the problem as a way of keeping peace. In Jack Robinson tackles explicitly the history of race relations in America by setting her story in 1950s St. Louis, where the divides between blacks and whites and the regulations between their relationships aligned more with the Jim Crow South than the Midwest. The story follows the romance between the wayward white Jack Boughton and the gentile black Della Miles, an interracial Romeo and Juliet plot that delights contemporary readers but would have been unfathomable to publish in its historical era.

The opening of the novel provides one lengthy scene of epic proportions: Jack and Della accidentally/providentially meet in a white cemetery where they are locked in overnight. Their conversation among the tombstones turns to apocalypse, poetry, their innermost confessions. For those familiar with the Gilead series, Jack’s admission that he is the “Prince of Darkness” seems apt after all we know of his history and how he robbed a young girl of her innocence and let their child die of neglect. When Della confesses to wrath, we understand: what African American would not be angry at the unjust mistreatment and the limitations placed on one’s freedom to live and be in the world? At the end of their nighttime wanderings, they wash their face as though preparing to climb Mount Purgatory, as they envision the act, and thus the rest of the novel, readers imagine the two as suffering sinners destined for sainthood and Edenic union.

Between the two of them, they exchange books and verses, sharing their love for Paul Lawrence Dunbar and Hart Crane. The love for literature has freed their souls to see each other as souls. While Robinson’s story is a testament to the truth that people all image God, that we are embodied souls, it seems to be a story that expects readers to already know this before reading the story.

Perhaps the intended audience are those who believe in the equity of human beings without the theological premise for why we are all equal. Robinson describes her audience as those with “a tentative but very respectful interest in religion.”[4] In a sense, she writes for the “Jacks” of the world, the atheist deplored by the Church, who, in her words “may be on his way to God’s love and favor in a day or a year” but may enjoy his grace “even now because God knows his intention for him.”[5] This sentiment correlates with the wise words of the African American preacher Rev. Hutchins to Jack, “If He’s showing you a little grace in the meantime, He probably won’t mind if you enjoy it.”[6]

Although an apostate, having fled his family and turned away from the faith of his childhood, Jack begins to live for Della, to pursue the goods listed in Philippians 4:8, whatever is noble, right, pure, lovely, admirable. Like Dante whose love for Beatrice led to an encounter with Christ, this soul lost in the dark wood/cemetery moves towards goodness because of his love for Della. You can imagine why people love Robinson’s work. The world is dark and troublesome, but her characters find the beauty and goodness in it. For those despairing of the emptiness and hollowness of existence, Robinson provides a look upwards towards the eternal transcendent.

O’Connor in Contrast

Flannery O’Connor, writing in 1952-1963, wrote for a hostile audience that differs entirely from Robinson’s readership; she wrote for those within the Church who lived as though God was dead. As a narrator says of one character, “She was a good Christian woman with a large respect for religion, though she did not, of course, believe any of it was true.” This statement epitomizes how O’Connor viewed her readers. Perhaps both Robinson and O’Connor find respect for religion in their reader, but O’Connor thought this respect was not enough to face the evil in the world. She writes to convert readers, to shock them into guilt, to bring them to a moment of self-knowledge in which they judge themselves by the Truth and not the other way around. Whereas Jack examines himself by being surrounded by mirrors in a dance studio, O’Connor’s characters must confront the devil they are possessed by; they must see themselves by God’s eyes through the icons, by the rubric of the scriptures, by the evidence in the newspaper, and at the end of a gun.

In our distracted age, Robinson’s novels are welcome antidotes, for they compel readers to slow down, to meditate on her sentences, and to contemplate the images that she sets before them. O’Connor writes stories that act on us like a Johnny Cash song—“steady like a train, sharp like a razor.”[7] They are both acting against the narratives offered by our culture that we are mere consumers and expressive individualists. They are both adhering to Christian doctrine over impotent talk of “personal savior” or kitschy bumper sticker versions of faith. And both of them confront white bigotry, especially within the Church where such prejudices should be anathema. Does the aesthetic and theological divide, then, have more to do with their particular homes within the Church, Protestant versus Catholic?

Protestant Versus Catholic Imagination

Theologians have debated Robinson’s work as Calvinian and Calvinist. They show how she draws inspiration from Jonathan Edwards and how her fiction is reminiscent of Bonhoeffer’s theology. In fact, Robinson writes as though she is preaching. In Gilead the epistolary genre hides the didacticism of the narrative, but in Jack, his existential angst and interior monologue dominate the story—a bit like reading the more introspective sections of Augustine’s Confessions. Likewise, the emphasis in Protestantism is on preaching. In The Givenness of Things, Robinson uplifts sermons as the act “to speak in one’s own person and voice to others who listen . . . For this we come to church.” She meditates on the communication between people as the central part of the church service. When Jack attends an African American church in St. Louis, the preacher steps up to the pulpit to “speak my mind,” in his words, “That’s my job.” Jack feels targeted, remembering all the years that his father preached on him and his waywardness as the “sermon text.”[8]

Yet Lauren Winner argues that preaching should be about more than the exchange of ideas. She borrows a familiar O’Connor phrase in her pushback against Robinson’s claim: “If the sermon is just one person talking to other people about important things, to hell with it.”[9] Instead, pastors and priests pray before they begin explicating the scriptures to ask for God’s words and for God’s Spirit to move in the listeners as well. The Word should be at the center of preaching, and those in the room commune on it. There is an authority to the expositor as a mediator of interpretation and an expected humility on the part of the recipients in the congregation. If Robinson’s way of understanding preaching parallels her stance as a writer, she hopes as author to convey matters of significance to another person, her reader. However, unlike our reading of O’Connor, in Robinson’s fiction, we should not expect revelation, prophecy, or analogical vision. We should expect a respectful discussion.

Alternatively, O’Connor considered her writing a “hymn to the Eucharist,” the centerpiece of Catholic mass. To become the body of Christ is a mystical gift through the sacrament, one not cognitively attained. Whereas Robinson’s fiction is intellectual, O’Connor’s is imaginative. We could enjoy Robinson’s fiction transferred to screen—it would be like watching one of Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales. But O’Connor, as a descendent of Dostoevsky’s drama, would need her stories performed on the stage. Her world is not only dramatic but also sacramental; the meaning is in things—from the red sun to the tattoo on Parker’s back. Thus, while Robinson rationalizes sin into “impulses,” as Jack calls them (though Rev. Hutchins tries to label them “temptations”), O’Connor images sin as fatal, akin to getting gored by a bull. Robinson says that O’Connor does not “credit” her characters with “enough intelligence” to have a soul.[10] Yet, the soul in O’Connor is more than mind; it is enfleshed.

Enlightenment Versus Medieval

Instead of delineating these differences as merely Protestant versus Catholic, since we have already seen those confessional boundaries collapse in some of what I said above, it might be more appropriate to engage them as post-Enlightenment versus medieval. In imitation of a good nineteenth-century theologian, Robinson prefers to think through problems, so her characters do as well. One reviewer lamented that Ames and Robert Boughton sound unrealistic as preachers because their conversations focus more on theological debates than pastoral concerns, facilities needs, budget problems, and so forth. Where is the mundane in all this realism? Where is the body? Whether the character is John Ames or Jack Boughton, Robinson’s characters struggle interiorly with a host of philosophical dilemmas more than against their demons. Perhaps that is why some readers misinterpret Robinson’s fiction as though it were “a Thomas Kinkade painting.”[11] Jack’s whole goal is not to keep from evil or try to be good, whatever that might mean, but to be “harmless.” Even her attempts to deal with sin sound like ethical predicaments rather than temptations towards evil.

In Robinson’s cosmology, fallenness becomes a misunderstanding to be solved by attention to the gift of creation, love for one’s neighbor, and true communication. These are real goods, but they are little more than a weak humanism in the face of horrifying injustice, violence, and suffering in our world. Too many readers, like Robinson, commit the error of seeing O’Connor’s fiction as misanthropic, accusing her of not loving her characters. In defense of O’Connor, she believes that the “friends of God suffer.” Violence is something that O’Connor describes as an observed reality, not something that she causes or enjoys. What shocks readers is that, as Rowan Williams says in his defense of O’Connor to Robinson, “that’s not the whole story.”[12] Instead, God works through the tragedies that we cause for our redemption. What is the Crucifixion but the bloody mess we make when God offers us his love? Yet, we praise him for the salvation and resurrection that he works through our own destructiveness.

In the medieval world, people meditated on the crucifix, on the cross. In The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ (a book that deserves much more than this sentence of attention), Fleming Rutledge shows that the crucifixion is the mainstay of our faith; it is the foolishness of our faith. She points out that it is not the teachings of Jesus that Paul quotes over and over but the “cross.” O’Connor’s characters suffer violence because Christ did. They are purged of sin in imitation of him. Like a true medievalist, O’Connor rewrites the story of Christ’s gory death without wincing from its reality. Of her own work, O’Connor said the Incarnation was central, but by this she points to the cross, the resurrection, and the Eucharist.

The Cross and Racial Justice

Although some contemporary critics have accused O’Connor of racism, her fiction was, as Hilton Als asserts, progressive for its time. In “The Artificial N—” O’Connor depicts race as an artificial construct, and that racism must be taught to persist, which means it also can be trained against to die out. Als writes how we hear throughout our current culture the echoes from “O’Connor’s voice the uneasy and unavoidable union between black and white, the sacred and the profane, the shit and the stars.” O’Connor knew her own sins, and she tries to eradicate them in her fiction, as she hopes to purge her readers from them as well. In her unpublished manuscripts where O’Connor attempts to fictionalize cross burnings that occurred across from her farm, she seems unable to unmask the evil in these events that haunted her. If only James Cone had written The Cross and the Lynching Tree 50 years earlier, if only O’Connor had read Countee Cullen’s poems where he imagines Jesus as “the first leaf in a line / Of trees on which a Man should swing / World without end, in suffering / For all men’s healing, let me sing.”

For African Americans in the Church, the cross provides hope that many other messages fail to provide. One can speak of grace and mercy all day long, but what do those words mean to those who have suffered decades of the lynching tree? O’Connor knew the centrality of the Crucifixion to the faith, not as one who longed for justice, but one who felt suffering in her very flesh. She endured lupus for fourteen years, and it claimed her life young at 39.

This year, she would have been 96, and I wish we could have seen what she would have written in the late 1960s, 1970s, and so on. Her suffering revealed to her the necessity of a God who suffers. If we extend suffering outwards beyond her physical ailments or our own individual difficulties and struggle to understand how whole cities can be destroyed by racism, how little children can be bombed, how innocent men can be hung or shot, we should demand a God who does more than comfort us but who can say, “Can you drink the cup I shall drink?”

The problem that I continue to have with Robinson’s fiction is that the cross looks so clean and empty in her work. In his explanation of Robinson’s metaphysics, Keith Johnson probes the abstract grace in her fiction: “But forgiveness without justice compromises goodness, because it tolerates evil.” Robinson focuses so much on human beings’ capacity for love that she neglects our penchant for evil. In her writing, evil is little more than happenstance, mistaken actions from generally good intentions, and thus the crucifixion of Jesus need not have happened. As she writes in her essays, she chooses to emphasize Jesus’s great love for us exhibited in the Cross, rather than the idea of sacrifice or atonement. Perhaps I am too much of a sinner to be satisfied with that depiction of the Cross.

In Jack when Boughton seeks Rev. Hutchins’s advice regarding Della, the preacher cautions him against a relationship, not because things would turn violent (which is what I would expect during that time period) but because Jack would not like Mr. Miles’s disapproval. Surely this explanation pales in comparison to the real struggle of Jack and Della’s situation in 1950s America. If readers are like me, they want Della’s wrath to come out. They disbelieve the easygoing nature of this relationship between people who would have been hearing racial slurs and have received regular threats to their lives. I expected Della’s brother to play the part of Mercutio and challenge Jack to a twentieth century version of a duel. Without the real sense that these two lovers are combatting not just disapproval but evil biases, their union falls rather flat. Not to mention how weak their sacrifice for one another appears. The drama of the Cross has been deflated.

Two Writers, “Both Alike in Dignity”

Regarding her dislike of O’Connor, Robinson admits, “I’m sure, I will, in some cosmic moment of justice, eat my words.” Her humility reminds me of the apocryphal wit of Karl Barth who, when questioned about a divergence he took from John Calvin, responded, “Calvin’s in heaven now; I’m sure he’s been corrected.” For now, as readers and writers, we exist in the broken space where we must give our imperfect works to him who will make all things new. Until the Lord perfects all our incomplete stories and thoughts, we must stumble forward as the Church, filling in the gaps for one another.

In Dante’s Paradiso two circles of wise sages circle the sun dancing together, singing one another’s praises. St. Thomas, the emblem of scholastic ministry, lauds the story of St. Francis, that dramatic theologian who brought sheep and asses into church on Christmas Eve that believers might see and smell the humble circumstances of God’s birth in the Incarnation. Although a Domincan, St. Thomas concludes by chastising his own order for giving into gluttony and other temptations. Following St. Thomas’s biography, St. Bonaventure, a Franciscan, relays with admiration the life of Dominic, who taught the world doctrine and ensured faith would be free from errors. He then chides his own order of Franciscans for going astray. Might we imagine a paradise where hedgehogs and fox wheel around the sun dancing while Dostoevsky and Tolstoy praise for their gifts, respectively, Robinson and O’Connor.

If we look to cathedrals, we see how the architecture represents the body of Christ as much as the believers that worship within them. On the outside are spires that point towards God and lift up the human heart with elation for his good gifts. They are beautiful. In the shadows of these spires hunch gargoyles with contorted faces and outstretched tongues. They have fangs. They are ugly. They warn you: do not enter this place with evil thoughts. While the spires of a cathedral remind us of God’s grace, the gargoyles exorcise our demons. Robinson herself has commented on the diversity of Christian denominations in America, “Christianity has a richer presence for the variety of its expressions.”[13] In this current kingdom, where we are all part angel and part beast, we can read both Robinson and O’Connor, on our journey towards that paradise where the saints sing.

[1] L’Espirit de Dostoievski (trans. A. Nerville, Paris, 1946)

[2] “The Revelations of Marilynne Robinson,” Interview with Wyatt Mason (New York Times Magazine, 1 October, 2014)

[3] Elisa Gonzalez, “No Good Has Come,” The Point (March 2021)

[4] “The Protestant Conscience,” Balm in Gilead 174

[5] Ibid 178

[6] Jack 167

[7] “Walk the Line” film quote

[8] Jack 222

[9] “Thinking about Preaching with Marilynne Robinson,” Balm in Gilead, 97

[10] “Conversation Between Marilynne Robinson and Rowan Williams,” Balm in Gilead 190.

[11] Gonzalez

[12] “Conversation Between Marilynne Robinson and Rowan Williams,” Balm in Gilead 191.

[13] “The Protestant Conscience,” Balm in Gilead (IVP 2019)