I think that if there is any value in hearing writers talk, it will be in hearing what they can witness to and not what they can theorize about. My own approach to literary problems is very like the one Dr. Johnson’s blind housekeeper used when she poured tea—she put her finger inside the cup.

These are not times when writers in this country can very well speak for one another . . . Today each writer speaks for himself, even though he may not be sure that his work is important enough to justify his doing so.

—Flannery O’Connor, “Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction” (1960)

It is clear watching Flannery, a PBS “American Masters” documentary about the life and work of Flannery O'Connor, that directors Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco, S.J. are enamored with their subject. One would imagine that this is a requirement for making a full-length documentary about any person. To be honest, it is refreshing—especially now as the weather warms and we mark the first anniversary of the COVID-19 lockdown and all the polarization that followed—to watch a film that is a celebration of a life, where all those gathered are unanimous in their love and praise.

But as a long-time reader and lover of O'Connor's work, I tuned in on Tuesday evening to my local PBS station (popcorn ready) with one eye squinted. Her good friend William Sessions, who is a sobering presence in the documentary, cautioned that the popular persona created in the nearly 50 years since her death was not, is not, could not possibly be O'Connor. The cult of Flannery, led by an exit-through-the-giftshop sort of marketing mentality to make her palatable to the contemporary reader who "demands," as O'Connor once wrote, "the redemptive act, that demands that what falls at least be offered the chance of restoration," is irritating.

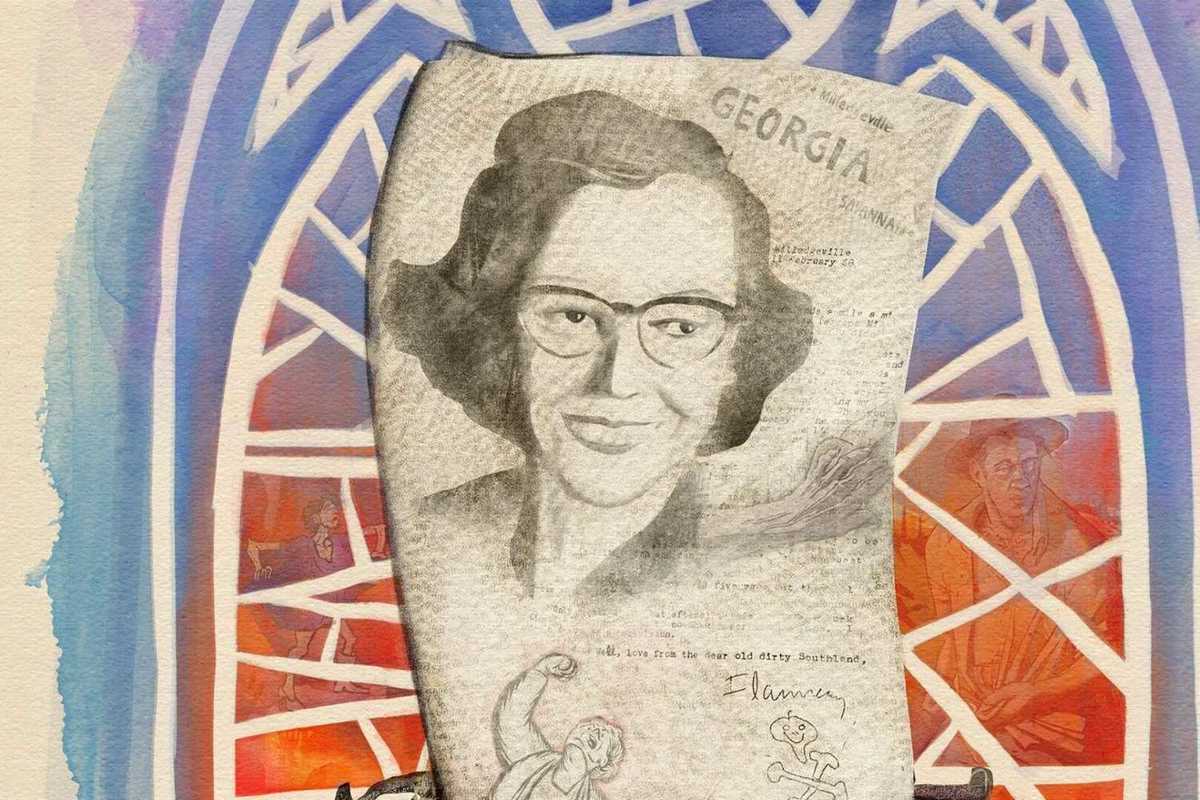

It is hard to imagine what she might have thought about the hand-lettered Etsy store quotations from her work, and the prints and t-shirts of a Cheshire cat O'Connor, represented synecdoche-like by her iconic horn-rimmed glasses. I was bracing myself for this to be another contribution to the Flannery-industrial-complex.

The documentary succeeds in striking a balance between hagiography and serious critical appreciation, but those who have read her whole output and try to stay current on scholarly conversations about her work will likely find it lacking in some key areas. For example, very little space is given to O'Connor's non-fiction on fiction and faith, especially touchstones like “The Catholic Novelist in the Protestant South” and “Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction.” These seminal works, which set the standard for what are today known mawkishly in the writer biz as "craft essays," are instead gestured toward as things written on the occasion of O'Connor being invited to this or that college or university to speak on things like "The South" or the job of the writer in society—work that merely paid the bills.

In lieu of engaging with O'Connor's own words on the craft, the filmmakers give us what we want: an illustrious slate of fans, friends, critics, and heirs to her legacy. Actor Tommy Lee Jones (whose credentials for speaking on O'Connor are unclear, except, maybe, that he played Sheriff Tom Bell in the Coen Brother's adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's ultra-violent No Country For Old Men) gives one of the first appreciations, followed closely by late-night talk show host and comedian Conan O'Brien, who is here to tell us that O'Connor was, not exactly to the surprise of O'Connor's readers, Catholic.

These celebrity appearances feel positioned to grab our attention, which they do, in that squinty-eyed way, but they also show how pervasive O'Connor's influence is; something that is unique and noteworthy, especially when one considers that there are precious few American writers from the 1950s and early 1960s who command such attention today. James Baldwin is one of these, and his relationship to O'Connor helps to broach the subject of O'Connor's attitudes toward race and racism, a topic that has been simmering for years, but came to a boil this past summer with Paul Elie's New Yorker article, “How Racist Was Flannery O'Connor?”

Baldwin, as is recounted in O'Connor's letter to her friend Maryat Lee in April 1959, was visiting Georgia and overtures were made to set up a visit between the two. O'Connor declines, writing that it would be too scandalous: "I observe the traditions of the society I feed on—it’s only fair. Might as well expect a mule to fly as me to see James Baldwin in Georgia." In another letter to Lee, not mentioned in the documentary, written just months before O'Connor's death in 1964, she writes: “About the Negroes, the kind I don’t like is the philosophizing, prophesying, pontificating kind, the James Baldwin kind.”

Apologists for O'Connor's racist attitudes, like senior O'Connor scholar Ralph Wood of Baylor, who appears only briefly in Flannery, have written that in such letters O'Connor is playing at the persona of a backwards, conservative, Catholic, Southern misanthrope set against her friend and foil, Lee, who, though also from the South, was Northern educated, an avowed feminist, and gay. In a 1962 letter to Lee, featured in the film, O'Connor begins: "Dear N***er Loving New York White Woman . . . "

What is interesting about the film, and will surely spark debate, is that O'Connor's distaste for Baldwin (and other "pontificating" Black leaders) and this apparent bombshell of a letter is defused by the support of two hugely influential Black writers, Hilton Als, whose 2000 New Yorker essay on O'Connor is one of the finest considerations of O'Connor and race not written by an O'Connor scholar (see Angela Alaimo O'Donnell's recent book for that), and The Color Purple author Alice Walker.

Both writers mount direct defenses against allegations that O'Connor was racist. Als defends O'Connor on the grounds that her work shows the "disruption of the fantasy of whiteness"—a point that is debatable and not universally held by recent critics of O'Connor. More poignant is his view that O'Connor was "an artist" not a "spokesperson" and so her rebuff of Baldwin in 1959 is strategic and crucial if she was to retain her deep cover as a "reporter" of what she saw.

Walker's comments will be shocking to some. She intimates that Southern white writers are victims of circumstance, born into "ideologies" that "they were often not able to see," and, as a result, unfairly "sold down the river"—a phrase that has its roots in the American slave trade.

Those looking for a serious treatment of O'Connor's faith and how her work engages with Catholicism might come away somewhat disappointed. Mary Gordon, Mary Karr, Tobias Wolff, and Richard Rodriguez, all writers who identify as Catholic, make appearances and make theologically-tinged observations. Gordon asserts how important bodily suffering was to O'Connor's work—a statement that deserves much more unpacking, and would have opened the door to O'Connor's interest in the Jesuit Paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, from whom O'Connor cribbed the title "Everything that Rises Must Converge" (and whose eugenicist beliefs have sparked controversy of late).

The documentary does not go into that mystical territory, nor does it enter into her late interest in the work of Dorothy Day. Those looking for a documentary that is decidedly more Catholic in its sensibility should seek out the excellent 2017 documentary by Beata Productions, Uncommon Grace.

But these directorial decisions are understandable considering the wide audience the filmmakers are clearly trying to attract. What is less understandable, and in my view, a near-fatal decision, is the use of lurid, comic book style illustrations to bring to life some of O'Connor's stories and absolutely miss the mark. It would seem that the directors were interested in capitalizing on O'Connor's dedication to the grotesque as a mode of representation and also the fact that, in college, she made a serious go at becoming a cartoonist—even sending some of her work to The New Yorker—but the result here is just cartoonish, which is very different than the grotesque.

The grotesque, as O'Connor understood it, is not merely illustrative of grossness; it is a kind of prophesying. It is a way of rendering visible those things that are hidden or far away; a way of bringing those hidden things closer and into the light. The animations in Flannery fail to do that. They lack the depth of O'Connor's most grotesque characters—The Misfit, Mrs. Hopewell, Hazel Motes, Hulga, or Manley Pointer—and do not feel not in the least urgent, threatening, or revelatory. And yet, the failure of these illustrations is proof of just how rare and inimitable a gift she possessed despite all the reservations we might have about her.

In the end, what is so complicated about O’Connor’s work and legacy is that she is both a racist and, as we know from those who knew her best, also aware of, and horrified by, her sin of bigotry. As Hilton Als suggests, she is a kind of double-agent: “She could only write about the South,” Als says, “if she was one of its citizens. If they met in Georgia it would be a Civil Rights cause and she would not be able to live in that town unobserved. And that was the whole point of writing for her was to be almost a reporter.” Or, as O’Connor metaphorizes at the beginning of her essay on the grotesque, she is the blind housekeeper who must put her finger inside the cup.