Maybe all theology in the end is confession, even if not so in grammatical form. Perhaps this is especially true of the theology of Joseph Ratzinger, who becomes in order Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI, and in his fading years pope emeritus. Confession is to the fore in his classic Introduction to Christianity and it is an unmistakable note of “here I stand and can do no other” in the myriad of essays he writes reminding us either of a truth of Christian faith or a contemporary untruth masquerading as the truth. Of course, to stand for and behind the truth is not an act of self-assertion. It is always “our” truth, the truth of the Church, the truth gifted to the Church in Christ, renewed in the Eucharist, and borne in prayer and action by a Church that is the “light of the world” despite the stains of sin and scandal that mar her.

The reluctance to opine, to invent, to be original does not signal that confession is impossible, but rather that confession only becomes possible, as Augustine suggested in the Confessions, when one has been released from vanity and, above all, the libido dominandi that is at the root of every individual act of sin and the agent of its reproduction and transmission. There is then the Augustinian paradox that in a sense constitutes the voice Ratzinger/Benedict: as the voice represents a silencing of self-assertion, it becomes more replete, and more transparent to God who loves us into being, remembers us with a passionate and heartbreaking fidelity, and who is both the ground and lure of our hope of true communion in and with his tri-personal love. However “objective” the voice of Ratzinger/Benedict may be, it is also and always personal. One could even say that it is deeply and abidingly existential.

This is what I want to suggest by borrowing the title of a great book on Romanticism by M. H Abrams, who would plausibly forgive me for transferring a distinction made in literary theory, to the theological domain, given his own penchant to transfer categories from the theological sphere to the literary. The “mirror” and the “lamp” are two metaphors, which literature does not own, indicating two quite different stances towards reality, the first, the mirror, indicating the interest in an accurate representation of the world, the second, the lamp, indicating a stance expressive of the self, its deepest motivations and hopes.

While across his oeuvre Ratzinger/Benedict overcomes this binary, I want to suggest that this is even more the case in his classic Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life (1977) in which he articulates his vision of Christian hope against the backdrop of the gravity of our being torn from this earth, at once beautiful and cruel, the scene of our greatest betrayals as well as loves, and undergoing a frightful disintegration that reason takes to be final. It seems apposite to speak to this text at this moment, even if one cannot validate it by invoking an anniversary. Even if the rumors of failing health that routinely come out of the Vatican can be dismissed as “gossip,” the Pope emeritus is now very old, very frail, and his life is moving inexorably towards its end.

This celebrated text of Ratzinger, now over four decades old, not only gives Ratzinger’s fullest statement of what Christian hope allows, but provides a space for himself and his readers to live through personally and validate in their dying the ecstasy towards God who is a God of the living. Ratzinger’s classic text is therefore at once a presentation or representation of the classic Four Last Things, death, judgment, heaven, and hell—thus a mirror—and a passionate plea that classical eschatology makes sense of each of our lives as well as our death—thus a lamp. Indeed, with only a little reaching it can be said that as Eschatology lays out the classical tableau of Last Things, it is self-involving in that it inscribes Ratzinger’s own movement through life towards death as an entry into the fullness of mystery, thus an encounter not with the void but with Christ who is the icon of the love that moves all things.

Eschatology in Light of the Mirror

In the foreword to the second edition of Eschatology, originally published almost three decades earlier, Cardinal Ratzinger looks back wryly at a time when he could act as a scholar and dig down deep into his subject matter. Ascension to various ecclesiastical offices had made that impossible, and due regret is expressed with regard to the book or books that did not get written. Because of his adamantine sense of mission, “due regret” is conditional rather than unconditional: to the degree to which he allowed only his likes, affections, and elective affinities into the picture, the backward glance at the first edition of Eschatology involved less a wrenching than an ache accompanied by the very brief burst of imagining a road not travelled that would joyously have involved long hours of study, reflection, and discernment that would go hand in glove with the contemplative he naturally was.

In any event, though it may have come across as written by a quite independent edition of himself, the future Pope Benedict XVI felt sure that it was a kind of text he could stand behind, one that married technical capacity with theological imagination in speaking to the Four Last Things, all the while being faithful to Church doctrine and in line with the broad Catholic tradition, and especially in line with Aquinas and Bonaventure, whom he was always reluctant to choose between, and his beloved Augustine who grounded both. He understood his text then, as well as at the time of writing, to be an intervention at a moment when theology seemed to have left behind—or at a minimum become embarrassed by—the highly reticulated eschatology of the intermediate state where the soul separated from the body awaited the general judgment and resurrection of the dead. From his perspective, none of the arguments against the classical view could be sustained either on biblical grounds or on grounds of the tradition. Nor did he find persuasive any of the alternatives that had as their base the view that death involved the immediate communion of a human being in fully resurrected form with Christ.

The argument for the traditional view of Last Things constitutes the focal aspect of Ratzinger’s theological intervention and makes sense of the chapters that deliberatively treat of death, judgment, heaven and hell. In the case of the latter, while Ratzinger found it easy to shuck off the pornographic and phantasmagoric violence of the retribution meted out to evildoers in the non-canonic apocalyptic tradition, on biblical and traditional grounds he felt obliged to affirm its reality while lifting up the mercy of God. What constitutes the horizon for the intervention, however, is less issues of adequacy regarding the traditional view and problems with the theological alternatives, both of which operate broadly in terms of a traditional grammar of the afterlife, than the proposal of an entirely different eschatological grammar. Historically speaking this grammar came into existence in biblical studies at the beginning of the twentieth century with a host of German biblical scholars drawing attention to the acute eschatological consciousness of early Christianity concerned with the in-breaking kingdom of God that transforms a world in which wealth and prestige rather than justice is the shared value, and where only some count, others little, and some not at all.

If it was biblical studies that inaugurated the paradigm shift of the kingdom away from heaven and the afterlife to the transformation and rectification of the world, in the middle 1970s in which Ratzinger was writing the text the contemporary instance of the new grammar was provided by the theology of hope, which found its most influential representative in Jürgen Moltmann, and its foundation in the thought of heterodox Marxist Ernst Bloch who, self-consciously arguing against an Augustinian view both of history and eschatology, thinks of Christianity as providing the immanent utopian code that expresses itself later in the visionary Benedictine, Joachim de Fiore (1135-1202), the Anabaptist, Thomas Münster (1489-1525), and latterly and crucially in Hegel and Marx.

While Ratzinger devotes the bulk of Eschatology attempting a persuasive rendering of the traditional eschatological model, in hindsight we can see the future Pope tentatively enter into the thickets of exegesis to chasten the political view of the kingdom of God to which the academy seemed to be in thrall and to question whether the theology of hope is any more adequate to the theological tradition than it is to the scriptural word. Ratzinger argues that the kingdom of God is not simply a set of mandates for the transformation of society that corrects wrongs and brings about greater freedom and equality. With regard to the kingdom the prophetic imperative is ineluctable. In the light of Gaudium et Spes Christians are obliged to do everything and more when it comes to the poor, the stranger, the outcast; they are mandated to do everything to ensure that those who are invisible become visible, and enable those who are voiceless to have a voice.

At the same time, the kingdom cannot be reduced to the prophetic imperative. It is not only that history gives numerous examples of reversal of such critique, with Marx’s prophetic discourse being turned into a justification of tyranny being the prime example, it overlooks what is most important. From a biblical point of view, the critical clue is missed that in the New Testament the kingdom is tied specifically to the person of Christ (autobasileia) who is the hope of the world because in him the kingdom is already realized. At once the burden of manufacturing the kingdom is lifted from human beings, while setting them free to participate in the bringing forth of the kingdom that is not yet fully realized. Though the worldly dimension cannot be erased from a theological account of the kingdom, neither should the immanent and transcendent dimensions be confused. The power of death means that the transcendent dimension remains enduringly relevant.

In Eschatology Ratzinger wished to maintain a distinction between the kingdom of God and the kingdom of the world that is disavowed by the soft Marxism of Moltmann. Cleverly—whether intentionally or not—Ratzinger’s refusal of the theology of hope seems to mimic the language of Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach. He insists: “The kingdom of God is not a political norm of political activity, but it is an ethical norm of this activity” (59), and proceeds to draw a line in the sand between the path followed by Jesus and that of the Zealots (60). Influenced by Solovyov’s and Dostoyevsky’s reflection on the anti-Christ—an influence that is still in full-force in his encyclical Spe Salvi (2007) and in Jesus of Nazareth—Ratzinger judges that an interpretive stance overdetermined by political rectification yields to the temptation of confusing the kingdom of God with the kingdom of the world. As he does so, he is conscious that he is supporting Augustine’s political theology that is anathema to Bloch and on his authority the object of critique in Moltmann.

Two particular points might be noted. First, Ratzinger’s balancing act between the immanent and transcendent dimensions of the kingdom are of a piece with his emphasis regarding the hermeneutic of Vatican II, that is, the responsibility to retrieve Lumen Gentium together with Gaudium et Spes and not set it aside as if it belonged merely to the letter and not the spirit of the Council. Second, Eschatology is a very different book than Hans Küng’s Eternal Life?: Life After Death as a Medical, Philosophical, and Theological Problem (1984). Unsurprisingly, given that these two theologians seem theologically to be mirror-images of each other, they have a very different understanding of the nature of his theological and apologetic task.

Judged in light not only of Eschatology but also “Some Current Questions in Eschatology” (1992), which comes out of the ITC but definitely bears the imprint of Cardinal Ratzinger, Küng can only be seen to have essentially set aside the theological task by abrogating the responsibility to speak about death and eternal life both from and to the Church. In addition, on the apologetic front Ratzinger thought that the more urgent challenge to be met was not that posed by secular unbelief, but rather by the reconstruction of Christian faith proposed by political theology in general and the theology of hope in particular. Precisely because the theology of hope appeals to the imagination rather than the intellect, it presents a far more compelling alternative to the classical eschatological tradition than the kind of intellectual reservations regarding the afterlife that Küng speaks to in his book on eschatology and with respect to which he prescribes Christian eschatology to dialogue and in due course come to some accommodation.

It is not surprising that in the Foreword to the second edition Ratzinger once again highlights his engagement with the theology of hope. After all his dissertation in the early 1950s is on Augustine’s political theology and his habilitation on Bonaventure is concerned with Joachim de Fiore and the immanentist pneumatic tendency in his apocalyptic thought which he is convinced has become the lingua franca of modernity to which all theology, not excluding Catholic theology, is exposed and in various measures intimidated. Whatever reservations Ratzinger might have felt about the lack of sustained argument against the theology of hope in Eschatology, in the essays that make up in Truth and Tolerance, again and again he strikes the note that the immanentization of the kingdom of God is a particularly acute problem from a theological point of view, and reminds that the basic grammar of faith is the refusal to identify the kingdom of God with the kingdom of man which, as Augustine pointed out, is always the kingdom of power and human apotheosis. Despite the lack of a sustained case against the theology of hope, on the basis of his later writings such an argument is easily constructed.

The first issue—one that was clear to those like Ratzinger who experienced both the horrors of fascism and communism in the twentieth century—is that it is not always easy to distinguish between the priority of the community and the priority of the collective, which disregards the individual and tramples on her freedom and her conscience. His question is John Paul II’s question: in terms of having a vision of community, is it any more sufficient to construct it by means of an appeal to the collective than by an appeal to the individualist modern subject? Inspired by John Paul II’s personalism, Ratzinger wants to say that when it comes to salvation the person and community are correlative. No person can call herself Christian if she fails to recognize the dignity of all and fails to wish eternal life for all. Equally, there is no community, if the irreducibility of each person before God is not crucial to its very definition. The second issue concerns the definition of the Church and whether there is any prospect in the political theology of Moltmann and others (e.g. Metz) to make the kind of avowal of the Church that is central to Lumen Gentium: the Church is sacramental, hierarchical, and participates in Christ even as it demonstrates time and again that it is not equal to this gift and continually requires forgiveness on God’s behalf and repentance on hers.

When writing Eschatology Ratzinger focuses his dispute with the theology of hope on the hinge issue of whether to think of redemption as occurring in history or being irreducible to history, though as he articulates judgment and death as eschata, one gets the feeling that should the theology of hope articulate them, it would do so otherwise than the classical Catholic theological tradition. This is certainly borne out by the appearance in 1995 of Moltmann’s definitive statement on eschatology, The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology. As is well-known, in Eschatology Ratzinger provides a spirited defense of Plato’s distinction between soul and body, or at least its Christian use in the theology of the intermediate state in which the soul preserves the identity of a lived bodily life and looks forward to the resurrected body, the spiritual body (soma pneumatikon) that Paul insists is the same, while radically different. Of course, the defense of Plato does not come from nowhere. It has been provoked by the theology of hope’s master narrative that in its history Christianity came to be dominated and corrupted by Platonism, thereby ensuring that classical forms of Christianity lack the appropriate emphasis on the body and the appropriate scriptural emphasis on resurrection.

Ratzinger denies all the charges, while recommending theology’s negotiation with classical philosophy and with Plato in particular. In his affirmation of Plato it is important to understand what Ratzinger accepts and what he rejects. He does not accept the reading of Plato’s metaphysical dualism in which the body and soul are two distinct metaphysical substances. Rather he accepts Aristotle’s emendation that the soul is the form of the body and largely follows Aquinas in thinking this to be the standard state for a human being. In classical eschatology, however, the crisis of death brings about the state of the exception. What if anything survives the trauma of death?

In light of the destructive phenomenon of death that puts the reality of survival in question, but also in light of the distinction between individual and general judgment (and thus resurrection) drawn from scripture, Ratzinger argues for the intelligibility of the intermediate state in which the soul alone continues to exist even as it waits for unification with its body. If the doctrine of the intermediate state was in the medieval period a more or less consensus view, in modernity most Christians are aware of it through the Divina commedia in which Dante succeeds in finding an imaginative correlative for a theological construct articulated with profundity and panache in the City of God. And it is Dante rather than Augustine and Aquinas who is to the fore in the twentieth-century apologetics of C.S. Lewis and Dorothy Sayers, both of whom divine that unless the poverty of eschatological imagination be overcome, there is little or no chance for a theological defense of the intermediate state upon which stands all Christianly credible views of the afterlife.

Beyond justifying a particular use of Plato that speaks to the separation of body and soul at death, Ratzinger is intentional in his attempt to rescue Plato from his would-be Christian detractors who sideline him with a clear conscience. While Christians cannot repeat Plato’s metaphysical dualisms, no less history and eternity than body and soul, what will prove nourishing to Christianity are Plato’s underlying motivations for speaking of postmortem existence and the deep existential concerns that issue in his positing a justice that is absolute, that is, not the justice that ratifies the power and morality of the victors, but the justice that is the expression of truth and goodness that countermands power and violence. This is a view that Christianity justifiably has taken over, even if because of revelation it has translated Plato’s impersonalism into a personal key.

Given the rampant injustices in history, Ratzinger thinks that Plato is being slandered by emergent political theologies: what criterion of justice has a theology of hope for those who have been sacrificed at the slaughter bench of history? More importantly, what form of rectification? Is it really sufficient that theologians-turned-prophets protest against history and demand justice? Is it enough to posit an end of history, whether arrived at incrementally or as an apocalyptic occurrence, where justice will reign? The problem is obvious: what about the totally broken and incomplete lives and even the less broken and less incomplete lives whose death leaves them beyond reach? What rectification for them? That in Endzeit we recall them, that we effectively either expand our list of heroes—those we make visible—by plucking some from oblivion, or just as likely changing our list of heroes according to a new set of criteria? Is there not, as Plato suggested, a distinction between immortality of name and real immortality? And with the move to the Christian dispensation is there not all the difference in the world between our impotent recall of these fragile bodily lives and the recall of God which preserves the bodily lives of human beings and their unique histories in an unaccountable remaking?

Ratzinger’s defense of Plato is best seen in light of one of what is perhaps the most dominant theme in all of his writings, that is, the compatibility of reason and faith. Still, this does not mean that Ratzinger does not make himself extraordinarily vulnerable in adducing Plato in a modern and/or postmodern context in which any compliment afforded Plato is likely judged at best to be anachronistic and at worst incurably wrongheaded. Ratzinger’s turn to the issue of justice and a trans-historical form of judgment is his basic apologetic move in that here Plato seems to operate in a truly existential key. Though this in itself is probably sufficient to mark the prospects for something like a rehabilitation of the philosopher who is the most criticized thinker in the canon of philosophy, it is clear that Ratzinger does not mount the kind of sustained and holistic defense of which he is capable.

In the moving section on death in Eschatology Ratzinger underscores how despite the distractions and evasions licensed in modernity we are beings-towards-death. There is good reason to think that Ratzinger has been reminded of Heidegger’s call to appropriate our ineluctable finitude, though Heidegger may well have been mediated in and through an encounter with Rahner’s theology of death. In the background, however, there is Plato, who in the Phaedo not only underscores death as the decisive moment of human existence, but suggests in his maxim that philosophy is the practice of death and that in one’s life death is a reality to be embraced in every moment. Death is not simply the separation of soul from body in a traumatic event in the indeterminate future, but a consciously enacted process from moment to moment in which distraction is cured, attention restored, enslaving projection abandoned and truth received. Death is also the site of the irreversible judgment as to whether one lived in truth or in the lie.

Eschatology in the Light of the Lamp

Thus far I have treated Eschatology as a magisterial text in which Ratzinger presented what he believed to be the position of the Church on Last Things, while also providing hints of the existential pathos that underlies their representation throughout Christian history. No less than the Creed, the best the Church has to offer on Last Things matters. Furthermore, as the Church’s confession of the truth of the former has deep existential as well as historical foundations, such is also the case regarding the confession of the latter. Nonetheless, this is still to continue to talk of Last Things in light of theological explication and thus within the light of the mirror.

But what about theological application of the classical eschatological model, how it is lived out by the Christian subject becoming ever more conscious of life’s end and the summing up in and through judgment whether that is imagined as a self-judgment or a judgment issued by Christ or at the very least a judgment issued because of him? What about Ratzinger’s eschatology in light of the lamp, that is, in light of the non-reproducable appropriation of finitude that death makes possible? Though the confession on our lips is the confession of the Church concerning Last Things, its purpose is to be owned and that it become the expression of an unsubstitutable subject standing before God.

As his life winds down, both the rumors of the pope emeritus’s imminent demise and the vehement denials may or may not make into the Mater Ecclesia convent in the Vatican where the pope emeritus spends his time praying and reading, and receiving the occasional visitor. Should he hear either they would likely have no weight. More than ever his life is the practice of death. More particularly, his life moves toward a silence that has threaded the needle to memory and waiting. On quiet winter evenings he accepts without rage the bent back, the stiffened legs, the weakened voice, and the mind that works well enough but has to the extent possible begun to steer clear of the present. The light on the East side of Mater Ecclesia where he sleeps welcomes even on a chilly day, as it brings the hint of autumn, a memory of a breeze just right, neither hot nor cold, and a waft of oranges from the garden to go with the tinkle of a fountain.

The perfection is too much and too little; too much in that it tends to seduce one to believing that there cannot be more; too little in that it does not match up to the memories of the perfect imperfections of his growing up a devout Catholic who lacked the interesting angularity of doubt, and of his brother George whose store of kindnesses, he feels, never runs out. He remembers places too. Here memory is more voluntary than involuntary, glances at the picture of the cathedral at Munich where he had been archbishop and a drawing of his home town Marktl in Bavaria. The longing for home is deep. It is not only the smallness and neatness of the town that speaks belonging that he recalls, but the forest nearby, its light tinctured leaves, its irrepressible cool, the life happening in the tangled undergrowth, the nervous scuttling of small creatures that refused to be seen, and the birds creating a canopy of noise that would make Francis of Assisi ecstatic.

Neither can he escape the inimitable Pole. Pictures of his predecessor are everywhere in the convent dedicated to praying for popes. Everywhere his smile. Yet he is the mountain that he would not dare to climb; he is the one who taught him to love hearts, outsized and reckless, full of joy. It is down to Augustine now: he comes and goes when and where he pleases in the fractures in time in which the pope emeritus reads him and finds in turn that Augustine reads him, whose journey is coming to a close and who has been marked by a Church pliant and stubborn, holy and always straying into scandal. He is mindful that Augustine has laid down this double reading in classics such as the Confessions and the City of God, but nowhere as explicitly as in Ennarationes in psalmos in which his voicing of complaint, thanksgiving, wonder, and joy is Christ’s voice such that it is impossible to distinguish between sounding and resounding.

In the spirit of the convent the pope emeritus prays often, even as he understands that he is always learning how to pray, for prayer is a response to a word spoken first by him who wants you to be in communion with him. That the flesh has almost disappeared from a face that is moving towards the condition of bone excites no horror in him. Rather it evokes the tenderness for the flesh that the Word made holy by assuming it and thereby promising its resurrection. He believes, as fervently as he always has, in the promise, and in awaiting death is waiting on the eternal life to come that will arrive out of the impossible future. In his Eschatology the pope emeritus was ascetic in his description of heaven other than lay it down that it consisted of a person’s fullness of communion with Christ and with other persons, and perhaps through these genuine communions with oneself. And hell—however populated or not—was understood to be the breakdown of communion and the construction of a mirror world in which one is endlessly alone.

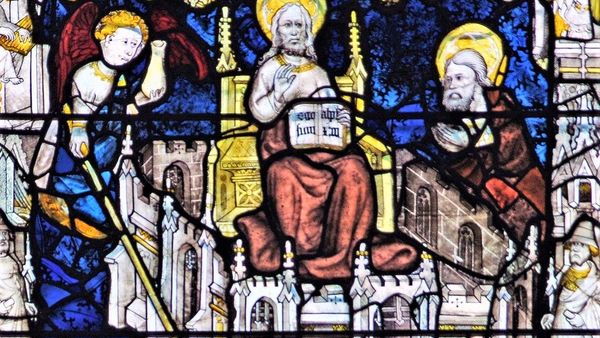

As a text Eschatology is more postulate than description, more conjecture than imagination. Too often imagination is only fantasy projection. The pope emeritus finds that old age happily reduces strictures. Imagination finds a space as it finds a rule. To read scripture, to resound it, is to become aware of what is promised: our bodies no longer in thrall, expressive of the gratuity of existence, infinitely capable of surprise and being surprised, being connected through love that has gone through the water and fire of forgiveness, and having learned how to praise and abide in the sharing laid down in the Last Supper. And, after Guardini, and understood properly, the pope emeritus is convinced that the liturgy tells us all that we need to know about heaven: it is there that we meet the High Priest and the Lamb whose fidelity has been as relentless as his love has been reckless, whose solidarity with us in our sin and alienation was the way to communion and the blessing of a peace that will not age and degrade into boredom.

Moreover, in the years that now seem to have flown the pope emeritus has come to see that heaven is beautiful and participates in the beauty of the triune God. The Confessions constantly remind him of this, though he knows that the meditation on divine beauty is Hans Urs von Balthasar’s gift to the Church. As a reflection of the principle that grace merely perfects nature, there is Mozart, the perpetual friend, especially his Coronation Mass and The Magic Flute. Or, a tune he plays on the piano just before he goes to bed, perhaps Ein kleine Nachtmusik, a celebration of joyous innocence. Sleep is not a curse; more a curator: every night is a night in which he might slip away into the dark. The thought does not confound. It releases hope that the end of the journey is the dazzling light of Christ and the profound sense that finally he has arrived at the beginning.