The city of Milan was in lockdown, at least for those less fortune residents who had no choice but to remain in their homes. The shadow of death was in the air as disease had returned to the northern Italian city. The “new normal” was the cancellation of Carnival, and a Lent in which no one could attend the celebration of Holy Mass or other processions. Hospitals were full. The public authorities were less than thrilled when the Cardinal Archbishop attempted to enter the hospital and provide Viaticum to the dying. And yet, there the Archbishop of Milan stood, offering the Blessed Sacrament, risking his very life that women and men might have their sins forgiven and receive the Body and Blood of Christ before they died (and many would). During this outbreak, nearly 6,000 citizens of Milan died in two months. Over 17,000 citizens of Milan would die over the year.

You probably know by now, that I am not talking about the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020 and 2021 (and likely 2022). I am speaking about the 1576 outbreak of bubonic plague in Milan. Although we have all heard of the Black Death (1347-1351), bubonic plague was a persistent threat to Europe and Asia for over 400 years. What follows will contemplate the saints that arose during this long period of plague. We do so not as an object of historical interest but as an invitation to think anew about sanctity in times of pandemics, to consider anew our response to our own plague.

Like many, I was first introduced to the Black Death through Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The dark, comedic moment in which the dead are brought out, tossed upon a cart (even if they were not dead) captures the real dis-ease brought about by the bubonic plague. It was not only the terror of the illness, of death, that caused such fear. Life was short in the first place. Rather, Black Death was an occasion of abandonment by Church and family alike. Normal practices of dying—ubiquitous in late medieval Europe—were replaced by getting rid of bodies. For most, there would be no viaticum, no last confession of sins, no Eucharistic liturgy praying for the dead, no procession from the home to the church and then to the grave. There was death, and death alone.

What is bubonic plague, and why was it so dreadful? The Black Death, or the Bubonic plague, is caused by fleas. Our forebears did not know this. Before the plague, “doctors” (a rather loose category) presumed that disease was caused by an imbalance of humors in the body: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. The imbalance of humors in the body would result in sickness—hence, the practice of bleeding.

Before we mock our forebears for this theory, let us remember that they did understand something about sickness, which we still struggle to grasp. Sickness and therefore healing is a holistic affair. Humors could be placed out of balance because of the quality of air, but also because of the sadness or sorrow in one’s life. Further, this theory of humors—even if incorrect—ironically led to the only way to treat the plague “Cito, longe fugeas, tarde redeas” [Leave quickly. Stay away for a long time. Come back slowly].

This advice worked in the end, because it enabled (at least the well-to-do) to escape from the bacteria that caused Black Death, Yersinia Pestis. Yersinia Pestis was passed on from fleas that fed initially upon the blood of rats. When the rats died, the fleas found news hosts. Either more rats, or when there were no more rats to feed upon, human beings who shared the very same spaces as the rats. Late medieval Europe’s population was growing rapidly, and they needed a new supply of food. Grain arriving from the east, ships bringing in goods across land and sea, re-introduced the plague into Europe in a swirling wave pattern that devastated every European country.[1] Although it is difficult to know exact death rates, plague killed off at least somewhere between 25% and 50% of Europe’s total population in five years. John Aberth estimates that England’s towns lost 60% of their population between 1347 and 1500.[2] To give a scope for these numbers, in the United States today, COVID-19 has killed roughly .2% of the United States population or around 680,000 people. To have a similar impact as the Black Death, COVID-19 would have needed to kill between 25%-60% of the U.S. population. That is, between 82 and 197 million people.

Dying from the plague was (and is) miserable. After the flea bite, the infected person would have between a day and a week before symptoms appeared. The flea-bitten person would have a black mark on his leg, experience fever, headaches, nausea, and unquenchable thirst. The lymph nodes would swell near the bite, giving the disease its name (bubo or bubonic plague). These swollen nodes swelled, burned, felt like thousands of needles were pricking one’s skin. The dying person produced a virulent smell out of every one of his orifices. The last physiological stage of the plague was systematic organ failure. In his book Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present, Frank M. Snowden writes:

By producing degeneration of the tissues of the heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs, and central nervous system, the systemic infection initiates multiple organ failure. At this point patients have wild blood shot eyes, black tongues, and pale, wasted faces with poor coordination of the facial muscles. They experience general prostration, teeth-shattering chills, respiratory distress, and a high fever that normally hovers in the range of 103F to 105F, in some patients reached 108F. In addition there is progressive neurological damage manifested by slurred speech, tremors in the limbs, a staggering gait, and psychic disturbances ending in delirium, coma, and death. Pregnant women, who are especially vulnerable, invariably miscarry and hemorrhage to death. Sometimes there is also gangrene of the extremities. This necrosis of the nose, fingers, and toes is one probable source of the terms “Black Death” and “Black Plague.”[3]

Imagine living over 400 years afraid of an outbreak of this plague, of a disease in which few recovered. And among those who did recover, not a few would be infected again. At least at first, there would be no herd immunity.

Like other diseases, the plague was not only physiological. Economic, psychological, political, and social unrest came along with the plague. Plagues were often followed immediately by famines. There were no workers to harvest the land, and supply chains shut down. In the case of the Black Death itself, an entire feudal system came crashing to a halt, while economic prosperity quickly followed due to the decrease in demographics. Psychologically, plague was an occasion of either religious, ascetic fervor or an Epicurean delight in music, dancing, and drink. Political distrust followed plague, especially early on, as leaders fled their cities and states for personal protection. Concurrently, the state began to take on more public health measures including sanitation and in Italy, the opening of lazarettos.

The social unrest caused by pandemic was especially virulent. Someone had to be scapegoated for the plague. And in towns, it was presumed the “stranger” was the source of a disease that could not entirely be explained by traditional medical theories.[4] Black death was too virulent, moved too quickly through entire populations to simply be an imbalance of the humors. In Germany, a theory developed that Black Death was caused by Jewish poisoners, who placed some potion in a well, infecting the entire population. Jewish persecutions arose in Barcelona, Bern, Basel, Frankfurt, and Cologne over the course of two years. Thousands of Jews were killed in cities, as pogroms spread throughout Germany. Poor Christians, vagabonds, and mendicants were also accused of working with Jewish Germans to poison wells. Any stranger was suspect, to be avoided, because he either had the plague or could poison the town well.[5]

Thus, like any pandemic, Black Death was not just about sickness of a person. It was a social and cultural illness that affected every dimension of society. And that included the Church. To understand the Church’s reaction to Black Death, something must be understood about lay medieval religious practice. A prominent narrative is that lay men and women were mostly spectators of a professional religiosity ordered more toward clerics than the baptized faithful.

This narrative is problematic, the result of Reformation era polemics rather than careful historical inquiry. While reception of the Blessed Sacrament was rare, late medieval society was suffused with a liturgical or sacramental culture. The individual stories of men and women were shaped by rites of the Church, especially the feasts and fasts of the liturgical year, as well as the presence of the Lord in the Blessed Sacrament. The liturgical feasts of the year were civic occasions—as Augustine Thompson has shown in his Cities of God: The Religion of the Italian Communes 1125-1325:

Feasts had a social as well as a religious role. Cities fixed their court sessions according to the liturgical calendar. Padua and Mantua courts scheduled recess from Christmas to Epiphany and during the week of Michaelmas (29 September). In the spring, courts closed from Palm to Low Sunday, the time of Holy Week and Easter Week . . . Courts always closed on Sunday. Christmas and Easter were the very minimum days of rest. Cities suspended sessions on the feasts of the Virgin, the apostles, and their local patron saints, including the titulars of every city chapel.[6]

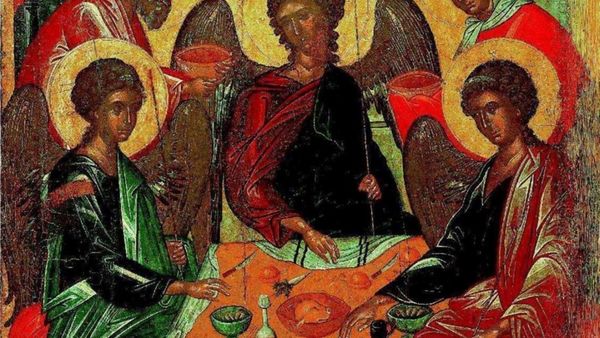

The Eucharist—as other medievalists have shown—was not only an encounter with Jesus Christ but a renewal of the social bonds of men and women. Kissing the pax board at Mass united Christians together in worship.[7] Seeing Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, what was known as ocular communion, was itself an occasion of union with Jesus. Medieval sight was akin to the sense of touch, and therefore to gaze upon the Host was to encounter Jesus.[8]

The ubiquity of liturgical practice also surrounded death. The Blessed Sacrament was carried with candles to the bedside of the sick. Men and women were encouraged to follow along, praying outside the house. Death was a public and thereby liturgical affair. Again, turning to Thompson’s account of Italian liturgical worship:

Led by the priest, acolytes and other clerics took up the cross and other items needed for the funeral. The men carrying candles followed two by two. After them came the bier, the widow, and last of all the women. The procession might stop along the way to let the women raise the pianto . . . Even if it did not stop, the procession passed through the major streets of the contrada, the deceased paying one last visit to the neighborhood . . . the community bade farewell to their deceased, commending them to the saints and angels who would lead them before the judge of all.[9]

Jesus Christ and his Church were therefore present throughout the lives of men and women. Especially in times of dying, when loved ones were carried home “together” to God. During the plagues, all of this disappeared. Liturgical feasts were postponed. Public processions ceased. The dead, even if buried in an orderly way, were not accompanied home to God.

What happened, for the most part, was abandonment. Now, this is not to say that every clergy member left his post, abandoning the city. It is clear, based on death rates, that many clergy died in the plague itself. The new mendicant orders, the Franciscans and the Dominicans, suffered a great number of deaths. But the entire liturgical-sacramental system of the Church, during the plague, was questioned. Who could hear the confessions and bring viaticum to the dying if there were no priests around? Worse, if the local priest fled the city for the sake of his own protection, what did this reveal about clerical commitment to the Church? Who would pray for the dying, especially if at least some family members abandoned their spouse, parents, or children? Remember the Cito, longe fugeas, tarde redeas?

We know, at least some ire during this time, was directed toward the Church. New lay movements came into existence including the flagellants.[10] A pilgrim group of penitents, the flagellants roamed from town to town, thousands in number and engaged in public penance. A master—not a clergy member—would whip penitents, while they cried out in lamentation for the sins of the Church and the world. Flagellants, although not always beloved by city or Church, were greeted with enthusiasm by the faithful. With the challenge brought about to sacramental confession, with so many dead, what were people to do?

EDITORIAL NOTE: This is the first part of the a three-part series on the Black Plague. We will bring you the next installments early next week.

[1] John Aberth, The Black Death: A New History of the Great Mortality in Europe, 1347-1500 (New York: Oxford University Press), 14-31.

[2] Ibid., 32-58.

[3] Frank M. Snowden, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 47.

[4] David Herily, Black Death and the Transformation of the West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

[5] Aberth, The Black Death, 169-194.

[6] Augustine Thompson, Cities of God: The Religion of Italian Communes 1125-1325 (University Park, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 274.

[7] Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England c. 1400-c. 1580, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 91-130.

[8] Hans Henrik Lohfert Jorgensen, “Sensorium: A Model for Medieval Perception,” in The Saturated Sensorium: Principles of Perception and Meditation in the Middle Ages, ed. Hans Henrik Lohfert Jorgensen, Henning Laugerud, and Laura Kathrine Skinnebach (Gylling, Denmark: Aarhus University Press), 24-71.

[9] Thompson, Cities of God, 407.

[10] Aberth, The Black Death, 145-168.