Medieval Rites

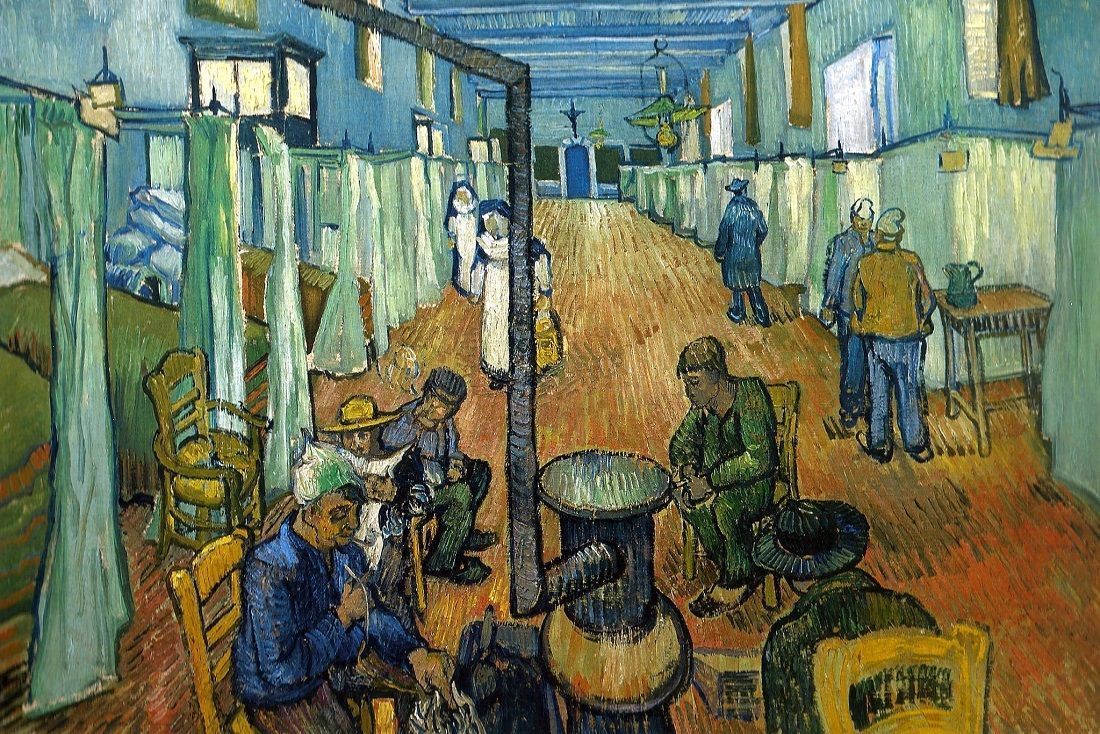

The scribes lived over 700 years ago, but their documents give us insight into the monastery’s practices when a brother became seriously ill: The leader of the community, the prior, came to the brother’s sickbed to hear his confession. The others gathered and processed to the infirmary with oil for anointing, incense, the communion host, a cross, and candles. They assembled in the room, singing antiphons and psalms as their sick brother was anointed. The gathered brothers sang songs of petition, using words from the Gospels: “Lord, come down to heal my son before he dies,” and songs of hope: “Jesus said to him, Go, your son lives.”[1] After the anointing, the brothers arranged a schedule so that at least one person remained always at his bedside. Prayers were said for him at the daily public Mass.

If the brother did not regain strength, but instead seemed to be nearing the end of his life, the entire community gathered again. In their brother’s presence, they sang a litany, naming members of the heavenly community and calling upon them to intercede, to protect the brother “from every evil.” And when the moment came—when his sufferings ended, when the soul migrated, when death occurred—one brother among the gathered community began to sing: “Hurry, saints of God . . .” The others joined: “Make haste, angels of the Lord, who are taking his soul and offering it in the sight of the Most High.” The brother who began the chant continued again by himself, singing words addressed to the departing brother: “May Christ, who called you, now take you and place you in the bosom of Abraham.” The community finished together: “Offering your soul in the sight of the Most High.”[2] They then offered a prayer: “Go forth, soul, from this world, in the name of God . . . ”[3] After the prayer, cymbals rang out to mark the end of the life. The brothers then began to wash the body and prepare for the burial rites, while singing chants and psalms.

This particular account is drawn from fourteenth-century manuscripts of the Augustinian priory of Klosterneuburg, Austria.[4] But such practices were not unique to that community. Medieval manuscripts throughout Western Europe reveal a rich variety of rites for the sick and dying, practiced in cathedrals, parishes, and monastic orders. Even in their diversity, the rites have commonalities:

- Music played an integral role. Chants were interspersed among prayers and readings; sung litanies often formed a large portion of the material for the time immediately preceding death.

- The community played an integral role. Community members provided physical care and offered spiritual support with their presence and prayers. Sickness and death were not individual experiences.

- Death was understood to involve more than the body. While ameliorating the physical sufferings to the greatest extent possible, sickness and death were also given spiritual responses and integrated into the liturgical life of the community.

Contemporary Dying

Distant as they are from our own time and circumstances, the medieval rites of Western Europe give us occasion—and comparative material—for reflection upon our own practices. Medical advances of the 20th century pushed death to the periphery of American discourse and—to the extent possible—to the periphery of our experience, displaced by hopeful, determined scientific research and treatments. We were privileged to develop a conception of death as a medical failure. But casting the doctor as the hero of end-of-life care has come with a cost. Beginning in the last decades of the 20th century, we began to articulate the cost and consider whether it is too high: loved ones dying in medical facilities, surrounded by staff rather than families; invasive, unsuccessful procedures that bring physical suffering to fragile bodies; family members caught unaware by death, having placed outsized trust in the potential of medical treatments.[5]

As a society, we are learning afresh to acknowledge the limitations of curative treatment and to accept sickness and death as an integral part of being human. As we re-discover our mortality and find ways to reclaim the ends of our lives from an overly medicalized model, the medieval rites offer us robust, developed traditions of confronting sickness and death and integrating them into the experience of communities. We do not look to the historic practices for scientific information: that is our specialization. We look to them for suggestions of how to respond to our weaknesses.

1. Acknowledging Mortality: Accepting the Gift

Where we have the tendency to avoid acknowledging and discussing the unavoidable fact of our own deaths, medieval communities did not. An open confrontation with mortality has benefits; it reveals that the end of life offers gifts not available elsewhere.

Clarity

An encounter with mortality can lead us to a discovery—or re-discovery—of our highest priorities. The sickness and death of someone in our community or the diagnosis of our own terminal illness tells us that time is limited; we are reminded of the ultimate deadline for living the good life—our best life. The pressure of mortality moves us to sort through the “many things” occupying us and determine our one “good part.”

When I was an undergraduate, the accidental drowning of a classmate became the central focus of the student body. In the time following Andy’s death, some of us left the high-powered conservatory to pursue teaching or music therapy degrees; some of us renewed our commitment to performing music as a way of offering beauty and solace to others; all of us participated in conversations that were decidedly more mature and urgent than before. The young man who had previously entertained us in the dining hall by imitating how dinosaurs ate now leaned across the table to ask, “If you knew you only had a few more months, what would you change? Would you keep doing what you’re doing now?” He is not alone in asking such questions in the face of illness and death. The confrontation with mortality can guide us to our highest good.

Community

The end of life offers us the opportunity to reconcile and strengthen our most important relationships. At the medieval abbey of Cluny, France, the rites for the dying began by gathering the community and allowing each person the opportunity to ask for and offer forgiveness.[6] The words of the dying Christ, addressing Mary and John from the cross, lay open this possibility of re-defining relationships: “‘Madam, look at your son.’ To the disciple he says, ‘Look at your mother.’”[7]

From my own experience, I understand well the authority of a dying person who strengthens bonds. My father called me to his bedside in the last hours of his life. He called my sister, as well. As we sat on opposite sides of his bed, we had to lean close to hear his words through shallow, labored breaths. “You two are very different. I love you both. This is not going to be easy for your mother. I need you to work together to help her. Will you do that?” My ego will probably fortunately never recover from that conversation. My relationship with my sister will never be the same, either. The memory of that exchange guards us from old patterns of indifference and false ideas of superiority. My father was a most gentle and soft-spoken person during his lifetime, but there is no arguing with him now.

My mother speaks of the gift of being able to care for him in his last days. She had the opportunity to express her love and solidify the depth and profundity of their 50 year marriage in many acts of service, large and small. Such experiences are not unique to our family. Those of us given the opportunity to be with our loved ones in the acknowledged presence of approaching death will have possibilities for expressing thanks, asking for and offering forgiveness, and uncovering the loving core of our relationships.

2. Death Involves More than the Body: Medical Resources as Tools

Perhaps the starkest divide between our own practices and those of the Middle Ages involves the presence of medical care. The medieval rites were honed and refined amidst an absence of meaningful pain control and symptom management; they guided people through physical agonies most of us will not have to endure, thanks to the accomplishments of our medical community. We face a different challenge. We must guard against allowing medical care to displace the spiritual and emotional aspects of the dying process. The medieval rites remind us that our humanity extends beyond our body. The rites could not relieve physical suffering, but they answered profound human needs: the need for comfort and assurance in the face of death, the need for reconciliation and affirmation of intimate relationships, the need for peace that passes intellectual understanding.

Contemporary medicine offers tremendous possibilities for end-of-life care. Our task is to communicate clearly with medical professionals so that resources for pain control and symptom management can be put in the service of the true hero—the person confronting mortality and living with full humanity in the presence of death. Our challenge is to subordinate medical resources to the service of the suffering person, to make possible the conversation or the last act of service he desires.[8]

3. Avoiding Isolation: The Community Gathers

The medieval documents are clear: “When anyone is sick, the brothers gather.”[9] The sickness and death of an individual engaged the entire community. Too often, our contemporary practices have the opposite effect: a sick person is drawn away from home, family, neighbors, and friends into an unknown medical environment. As we reconsider end-of-life care, providing ways of fostering existing relationships and keeping communities intact are paramount.

4. Incorporating Beauty: The Community Sings

The immediate response to death in many medieval communities was song. Why? In discourses of the time, music reflected realities beyond the human sphere; it joined the individual soul and the motions of the heavens. The words of the chant Subvenite—recorded above and sung at the moment of death in Klosterneuburg—depict a connection between the earthly and heavenly communities. The music itself would also have been understood to bridge the two realms. Music was considered capable of transforming chaos to harmony. If “music orders time, domesticating without trivialising it,”[10] what more appropriate response could there have been for the unfathomable moment when time ceased to be relevant for a loved one?

Regardless of how we conceptualize music today, we recognize its ability to incorporate beauty into sterile medical environments and transform chaotic, depersonalized surroundings into spaces of serenity. Music has an important role to play as we reconsider end-of-life care.[11]

Interactions: Re-enriching Contemporary Rites? Appropriating Material?

The historic material of the medieval rites might interact with contemporary care in a variety of ways, but from my perspective, the goal cannot be to re-create the rites within contemporary settings. The historic practices were developed by communities within the specificities of their own physical spaces, their own resources of personnel, and their own customs of interacting. A more appropriate goal, in my opinion, would be to use an examination of the historic practices to help us reflect upon and shift our actions towards more thoughtful and compassionate care—care that provides a greater place for the non-physical needs of the dying person, a greater place for community, and a greater place for beauty.

Those within the Catholic Church have the benefit of contemporary versions of the historic rites. Recovering material from the medieval manuscripts could enrich these current practices. Historic chants could contribute beauty; the practice of singing together—be it chants or contemporary songs—could re-affirm and re-establish the role of the community.

The melodies from the historic rites have the potential to extend beyond contemporary Catholic practices; they have the potential to function in diverse religious and secular contexts. Beauty is attractive. The musical parameters of timbre, pitch, and repetition have effectiveness and applications beyond that of spoken words and beyond any specifically religious context.

Meaningful ritual, practiced in circumstances of great need, is also attractive. This is evident in the current phenomenon of creating rituals to mark the profoundest moments of life.[12] Those of us who are privileged to be part of ritualized religion and who have experienced the solace of communal responses—transmitted and refined through generations and shared by those we love most—might have the ability and responsibility to reach out to those who are struggling with the same momentous events but lack the spiritual and liturgical resources.

The witnesses of the medieval rites invite us to acknowledge and address the suffering that occurs today in the fear and avoidance surrounding death, in the aggressive, curative treatments continued beyond the point of benefit, in the loneliness of a person isolated in a medical facility, in the loss of communal responses to an event so terrifying and universal as death. How we choose to manifest the faith, hope, and love so evident in the historic rites will differ, depending on whether we are stating intentions for our own end of life, attending to a devoutly Catholic parent, or visiting a friend confronting a terminal illness without a faith tradition from which to draw strength. The medieval witnesses do not demand one specific form or set of actions as we address the suffering of the dying; they simply ask us to begin.

From the author: With gratitude to the fellows at the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study, undergraduate research assistants Jarek Jankowski and Yutong Liu, as well as Professors Lacey Ahern, Kimberly Belcher, Thomas Burman, Michael Driscoll, and Timothy O’Malley for rich conversations on the medieval rites for the sick and dying.