- To have reneged on beauty, as considerable parts of the Christian tradition have done, is to have cast aside phenomena that open up depths of meaning and truth to which we are attracted and to which we feel compelled to give our assent. Even more importantly, it has reduced the purchase of Christianity, for as the phenomenon of phenomena in the end Christ is neither fact nor rule but the reality who enthralls, consoles, and energizes.

- Art provides us with ears to listen, eyes to see, and language to express where God’s love is signed in matter and history and often enough in blood.

- Beauty will save the world. Yet it will do so only to the extent to which it opens out beyond our standard notions of aesthetic order and leads us into a depth in which the wounds and disfiguring death of Christ are paradigmatic. The enormous coverage given to literary production in a theological oeuvre is simply a homage to the intimations provided by art of the disclosure of reality that make for human integrity consistent with an ecstatic and caring relation towards the world, others and God made possible by and secured by the Cross.

- The glory of God (kabod, doxa) is God’s absolute otherness as it approaches us in solicitude and love with the aim of transforming us and thereby enabling us to participate in the dance of divine life. God’s love is vulnerable because the glory of God respects human freedom. It persuades rather than coerces. The drama of divine glory in its manifestations and the correlative human response is what unites the Old Testament and New Testament and equally forbids Marcionite reductions and Gnostic speculative elaborations.

- Catholic theology will find itself again when Christ is no longer simply the object of our reason and even our imagination, but their subject and their regulator in cooperation with the Holy Spirit.

- The great “world-stage” motif shared by Calderon and Shakespeare is a metaphor for the drama of existence Christianly specified. If the person of the Father can be appropriated to the dramaturge, the Spirit to the director, and Christ the Son to the central protagonist around whom the plot weaves, we are the players on the stage involved in improvisation and playing our role well or poorly. How we act matters utterly and has eternal and not simply temporal consequences. While it risks being facile, there are obvious links here between the great Swiss theologian and C. S. Lewis despite extraordinary differences in style.

- There is a logic of divine love that is more than reason. Though intrinsically intelligible, this logic can be seen clearly to sidestep the law of contradiction when it comes to Christ and logical necessity when deployed to understand creation. The incarnation, and the Cross even more, belong to the order of paradox. The creation of the world is why-less. Moreover, the building up of the communion of saints does not obey the law of sufficient reason. Yet all of these acts are fitting and becoming of who God is and render God precisely. There is much that is different in the theology of Balthasar and those of Hans Frei and David Kelsey. Enactment of character, however, is not one of them.

- The Catholic tradition is not only the memory of the doctrinal formulas and magisterial pronouncements of the Church, but also of the myriad ways Christians have responded in word and silence, conversation and argument to the glory of God as testified to in scripture, enacted in liturgy, and expressed in ascetic and mystical forms of life as well as in common acts of charity that flow from being a disciple of Christ.

- The Church’s art of memory is to remember broadly and deeply. Its task is not to remember everything and certainly not everything at once. To think otherwise is to think of tradition as moving towards the condition of an encyclopedia or a museum. Memory is selective: from the store of memory it puts into play, first, what makes for the Church’s perdurance and, second, what is apt for the current moment. While judgment and prudence, which are always in stunningly short supply, are necessary if tradition is to be alive, in the final analysis the agent of memory is the Holy Spirit who alone can read the signs of the times in the hour of our need.

- The erudition displayed by a Catholic theologian is in the service of the Church’s memory. It should not be read as an expression of the cultural superiority of the theologian. Consequently, it should provoke neither idolatry nor resentment. Erudition is especially not to be confused with elevation to the divine point of view. This is not only to confuse much knowing with all-knowing, it is to mistake the purpose of erudition: to point out to us in a time in which Christianity is assailed from without and hollowed out from within just how many resources the Church has available to her to sustain the individual Christian, to enable conversion, and to evangelize the world and especially a post-Christian culture. Not just the number of resources, but their variety, is the best hope of seeing us through the night of the erasure of Christian truth and hope.

- To be a lover of tradition is not to be a lover of the past as such, but a lover of the past to the extent to which the past bears on and is potentially transformative of the present. The Church loves the medieval not for itself as, for example, in Chateaubriand, but because of its fidelity to the revelation of Christ and its opening of the horizon of the triune God. The Church loves the Fathers for being inceptional as well as exceptional, for being font and fountain refreshing us in the here and now.

- As the Church finds its ground in the self-giving of Christ on the Cross, it finds its archetype in Mary’s yes, which puts all that one is at the disposal of God’s will to save the world. With respect to the latter Balthasar anticipates Lumen gentium every bit as much as de Lubac. Other obvious lines of affinity with de Lubac include the Church considered as the mystical body and the bride of Christ. In addition, as much (if not more than) de Lubac the Church is dynamic rather than static, an ecstasy rather than a reality with the posture of staying at home. While the basis of the Church lies in God’s gift of self from the foundation of the world, its orientation is to the apocalyptic Second Coming of Christ that provides a real symbol of God as the absolute future.

- The Church is not the magisterium, but the entire body of the faithful united across space and time, distinguished by different charisms, spiritualities, and practices cooperating in the building of the kingdom of God that begins in this world and finds fruition in the next. The reminder of the Catholic whole, however, does not subvert the office of Peter nor suggest an inalienable conflict between the Church as institution and the Church as prophetic and contemplative.

- There are good and bad ways of sounding the Catholic “and.” One of the more problematic ways is to speak loosely of scripture and tradition as if the relation were entirely extrinsic. One avoids speaking loosely when one reminds oneself of two things: first, that scripture is itself the fruit of Christian reflection; and second that the theological and magisterial traditions are normed by scripture as disclosive of the God of history who at the same time serves as guarantor of the meaning and truth of the text that witnesses to this God. If the first reminder helps us to recall that the interpretive circle between scripture and tradition can never be broken, the second provides the basis for Dei verbum’s emphasis on scripture as the Word of God and not another artifact of culture.

- Catholic interpretation of scripture must necessarily be “catholic.” Given its superabundant disclosure of the meaning and truth of who God is and God’s relation to the world, Catholic interpretation resists all claims for the authority of a particular form of interpretation. This embargo applies to claims made on behalf of historico-critical method as well as claims to extract the essential kerygma of faith from its cultural integuments. Both are examples of the fallacy of misplaced concreteness and, ironically, examples of the very ideological formation they wish to uncover. When it comes to the general principles of biblical interpretation the line from the Swiss theologian to Benedict XVI is straight.

- The connection between Christianity and Judaism is as unbreakable as the link between the old covenant and the new. Thus, the rejection of ancient Marcionism, and even more the Marcionisms of the modern period that tout the superiority of the New Testament from either a moral or aesthetic point of view. If the general optics of the relation between the Old Testament and New Testament operate in terms of the patristic model of fulfillment, nonetheless, the covenant with Israel is irrevocable.

- It is not simply the case in Balthasar, as with the Church Fathers, that of the New Testament writings the Gospel of John is preeminent, it is that as Glory of the Lord makes clear that while the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke present unique perspectives on Christ and possess an integrity of their own, each point to the Gospel of John as providing the most expansive horizon for their singular contributions. The judgment here is just the opposite of the common judgment emanating from historico-critical circles about the belatedness of the Gospel of John and the excessive theologization that should be set aside in favor of the more theologically underdetermined Synoptic Gospels.

- Nowhere in modern Catholic theology does one find an equivalent highlighting of the Book of Revelation as the horizon of human imagination and the telescoping for God’s relation to and expectation for the world. Although the Book of Revelation is discussed in detail only once in the five volumes of Theo-Drama, it would not be an exaggeration to claim that the book of Revelation is everywhere in this part of the triptych and influences not only discussions of Christ, but discussions of the triune God for whom the Lamb is a real symbol, the drama of history and the Church’s place in it, and discipleship as constitutive of the Church. While Balthasar and Sergei Bulgakov have much in common when it comes to Christology and Trinity, arguably, the ground of their commonness is the elevation of the Book of Revelation.

- Central to the book of Revelation is the idea of the anti-Christ as the counterfeit of Christ and the extolling of a kingdom of the lie as the kingdom of truth. As in Solovyov and Dostoevsky, but also in Claudel, one of the most conspicuous problems of the modern world is the reality of anti-Christian ideology and demagoguery.

- Though Kierkegaard may be too angular when it comes to thinking the relation between nature and grace and too contrary when it comes to the relation between Christ and culture, nonetheless, he is right in thinking of Hegel as the great spider who captures and consumes Christianity in his dialectic web. Kierkegaard is also right when he thinks of Hegel as the counterfeiter par excellence: he presents a simulacrum of Christianity to us enervated and intellectualizing moderns who for reasons of nostalgia as well some inkling that not all is well comfort ourselves by wrapping ourselves in a Christian mantle.

- Heidegger is a hater of Christianity. Yet despite not abiding its truth claims, practices, and forms of life, his thought, early or late, does not seem to be able to proceed without reference to it. It is manifestly clear that as they function in Being and Time concepts such as anxiety, being-towards-death, care, and conscience are reworked versions of Christian equivalents shoved aside as superficial or in Heidegger’s language as merely “ontic” rather than “ontological.” And notions such as “event,” holy, unveiling, and the celebration of dispositions of openness, service, and stewardship, conspicuous in his later work, suppose the Christian mystical tradition rinsed of commitments to the worship of a transcendent God and the unrepeatable coincidence of eternity and time in Christ. Any welcoming of Heidegger into Catholic theology should proceed with the acknowledgment that Heidegger does not have the best interests of Christian faith at heart and that his thought is wedded to the order of immanence and the modes of worship proper to it.

- Nietzsche is enough of a prophet to show us the precipice and the free fall of the beliefs and values that have supported the view that there is transcendent meaning and truth. Yet he is not enough of a prophet to chart a way beyond it. His braggadocio evinces a lack of courage, an inability to avoid being a victim of the abyss he so ingeniously names.

- Pascal and Hamann are, arguably, the two great Christian agitators in a modernity in the process of coming to worship reason and morality. Both are unafraid to use hyperboles, precisely on the Christian grounds that there is more to human-being than can be dreamt in an enlightened philosophy. Both insist that read properly scripture is the lens to read the world and history and that neither natural science nor historical investigation are adequate to scripture’s capacious reach and luminous depth. Newman also comes across as something of an agitator, but one who is perhaps more focused and clinically precise. Newman is a Christian sniper.

- Christianity has to be grateful to Romanticism for reminding it at every turn of reason’s incapacity to take account of the full dimensions of human being and in the form of technology representing the clear and present danger of instrumentalizing and desecrating the natural and the human world. Christianity separates itself from Romanticism, however, when Romanticism claims the capacity to make individuals whole and to form a truly human community. For Romanticism at best Christ is the example of the former and the Church a failed instantiation of the latter.

- Augustine is not the great thinker of the “self,” but of the person ecstatically oriented towards the triune God who loved her into existence and maintained her, rescued her from her pride and alienation, and abides with her in her peregrination towards a life of realized participation in God. Nor is Augustine the thinker of the community not-otherwise-specified, as Hannah Arendt was inclined to think in her Heidegger days, but the thinker of the Church as Christ’s representative on earth throughout the travails of history.

- While Augustine, undoubtedly, contributes to our understanding of beauty and specifically the Christian specification of beauty in Christ and the mystery of the Trinity, he makes a far greater theological contribution in the City of God when he speaks to the agon history, the trial of the Church which, if it bears the kingdom, in its sinning also refuses it.

- Irenaeus is a particular thinker at a particular time, indeed a watershed figure who set down the basic contours for Christian belief and what necessarily fell outside. Yet in another sense Irenaeus is also a peculiarly modern figure who helps us diagnose and do battle with speculative systems that counterfeit Christianity and replace the Church by a spiritual elite.

- Origen and Irenaeus are to be loved in equal measure: Irenaeus for blunting imagination run wild by appeal to the fact of tradition and by directing attention to our creatureliness and the Cross which effects our salvation; Origen, for expanding our imagination and asking the questions that suggest there will always be mysteries that the mind will not fathom even when, or especially when, these mysteries are in plain sight.

- As with the Church Fathers and theologians throughout history, it is perfectly justified to think of Platonism and Neoplatonism as a praeparatio evangelica that can be made an instrument of Christian truth. Problems arise only when the spell of this philosophical language with its leanings towards an unknown God and spirit-matter split takes over. The Hellenization hypothesis is in fact an Enlightenment smear. What we might learn from it, however, is that a theology that would be faithful to the Gospels has to be perpetually vigilant against the prospects of a hostile takeover. Concretely, while there may not be enough basis to condemn unilaterally Gregory of Nyssa, Pseudo-Dionysius, Johannes Scotus Eriugena, Meister Eckhart, and Nicholas of Cusa, the question to be asked in these and in other cases is whether the philosophical discourses is expropriated or is doing the expropriating. Of course, there are examples of where the host Christian language and grammar is in the ascent. Maximus the Confessor, Bonaventure, Ruysbroeck are magnificent examples of where Neoplatonic philosophy becomes a Christian “spoil.”

- Christian mysticism is both essential and dangerous: essential because it is a necessary outgrowth of being a Christian who is invested in the economies of prayer, the mysteries of liturgy, and in the requirements of Christian life; dangerous, in that mysticism tends to suggest that there are two qualitatively different forms of Christianity. There are not. There is only the one Christian life lived at different intensities.

- The Christian mystical tradition famously prioritizes negative over positive language when it comes to God. It is important to make a sober assessment of the priority. First, the priority is functional rather than absolute: it is simply to say that all God-talk should be attended with a modicum of epistemic humility. It does not imply that there is an unknown God lying beyond the God grasped in scripture, related to in prayer and sacrament, and spoken authoritatively about throughout the history of the Church. Despite the hyperboles, there is no Godhead beyond God or beyond the Trinity.

- Since Christian mysticism is the experience of the presence of God that cannot fully be translated into language, rather than the experienced absence of God, mysticism cannot be spoken of as it were agnosticism or even atheism by other means.

- If direct discussion of Ignatius Loyola is fairly muted in the great triptych, nonetheless, it is clear that for the author who led the Exercises over a hundred times, Ignatius is a pervasive presence. Ignatius is a threshold figure at once medieval and modern. Yet it is even more true to say that he is the figure of the threshold, that is, of how under the conditions of modernity with its tendencies towards psychologization and affirmation of self, the Christian person can give herself entirely away and pledge her entire existence to the glory of God under the banner of Christ. The key concepts of Ignatius such as discernment (and indifference), obedience, and service indicate the depths of the biblical roots of his thought.

- It is not an insubstantial achievement to have articulated a form of theology in the modern period in which women appear. Not only Mary, but Mary Magdalen and Elizabeth; not only biblical figures, but eminent historical women such as Theresa of Avila and Catherine of Genoa, and eminent mystics such as Angela of Foligno and Julian of Norwich; not only medieval women figures, but modern figures such as Therese of Lisieux and Elizabeth of the Trinity; and not only modern but contemporary in the form of Adrienne von Speyr. While it is hardly true that Balthasar is really only Adrienne’s amanuensis, it is true that her visions and her biblical interpretations persuade him that theology is not simply archeology, but follows or ought to follow the direction of the Spirit that leads into the deepest truth. One may agree or disagree with Balthasar’s characterization of female spirituality and/or regret his close association with Adrienne. Crucially, however, judgment on these issues requires that women have appeared. This by no means can be taken for granted.

- The Christian life does not round into sense, even less self-knowledge. It is living a vocation that owns one rather than being owned. How the story turns out is God’s secret. God can be depended on to make up for the shortfall in our awareness and knowledge.

- We would rather stand. Yet it is on our weight-bearing knees that acceptance happens and we lose ourselves joyously in amen.

- Prayer is letting God in and the self out. Because this is its nature, it is extraordinarily difficult. It must compete with distractions, blandishments, and the immediate demands and goods of human living, just as it must compete with the person’s insistence of holding onto himself at all costs which, if urged by the relative autonomy granted in being creatures, is exponentially increased in us as sinners whose basic attitude is defiant self-affirmation. Prayer is never an act of heroism. For it to happen, God will always already have made it possible for the space to be opened up and we have been enabled to listen. It is only from the perspective of having been open up that you come to realize, as Augustine did, in the Confessions, that our calling on God was an echo of God calling on us. Our prayer is sound that is a resounding just like the delay and doubling of sound of the gunshot in the valley between sheer mountains.

- It does not matter whether you amble or run headlong towards your death. What matters is that you go into the darkness in faith and in hope of a brilliant morning in which love will have cast its shine over all that was vain and hopeless and will give us finally to each other at the wedding feast of the Lamb.

- Dostoevsky, Peguy, and Bernanos have done far more to elevate the role of the saints in Christianity than theologians and hagiographers. They have insisted that, paradoxically, in the night of modernity and the contempt of Christian piety, it is the saints who constitute a powerfully effective form of eloquence that can persuade of the truth of Christianity.

- Saints by the nature of the case are excessive. Their measure is no measure. Thus, their “foolishness.” Francis is a glorious example, perhaps Joan of Arc. Yet examples abound. Saints are given to the Church as shocks to the accepted way in which Christ is followed and to the world, as signs that when it comes to faith, hope, and charity, enough is never enough: one can hold a belief more firmly and trust more deeply; one can hope against all hope; and love beyond all that is possible for a human being. Perhaps with Kierkegaard we need to remind what scripture has told us clearly: what is impossible for a human being is not impossible for God.

- Theology depends far more on holiness than holiness on theology. Neither cleverness, nor intellectual brilliance are sufficient to make a theologian. The gifts of knowing are actualized only when the theologian has been opened up to God in conversion. Though there may be a difference in the language used, here the Swiss theologian and Lonergan are of like mind.

Changing the Subject to Christ

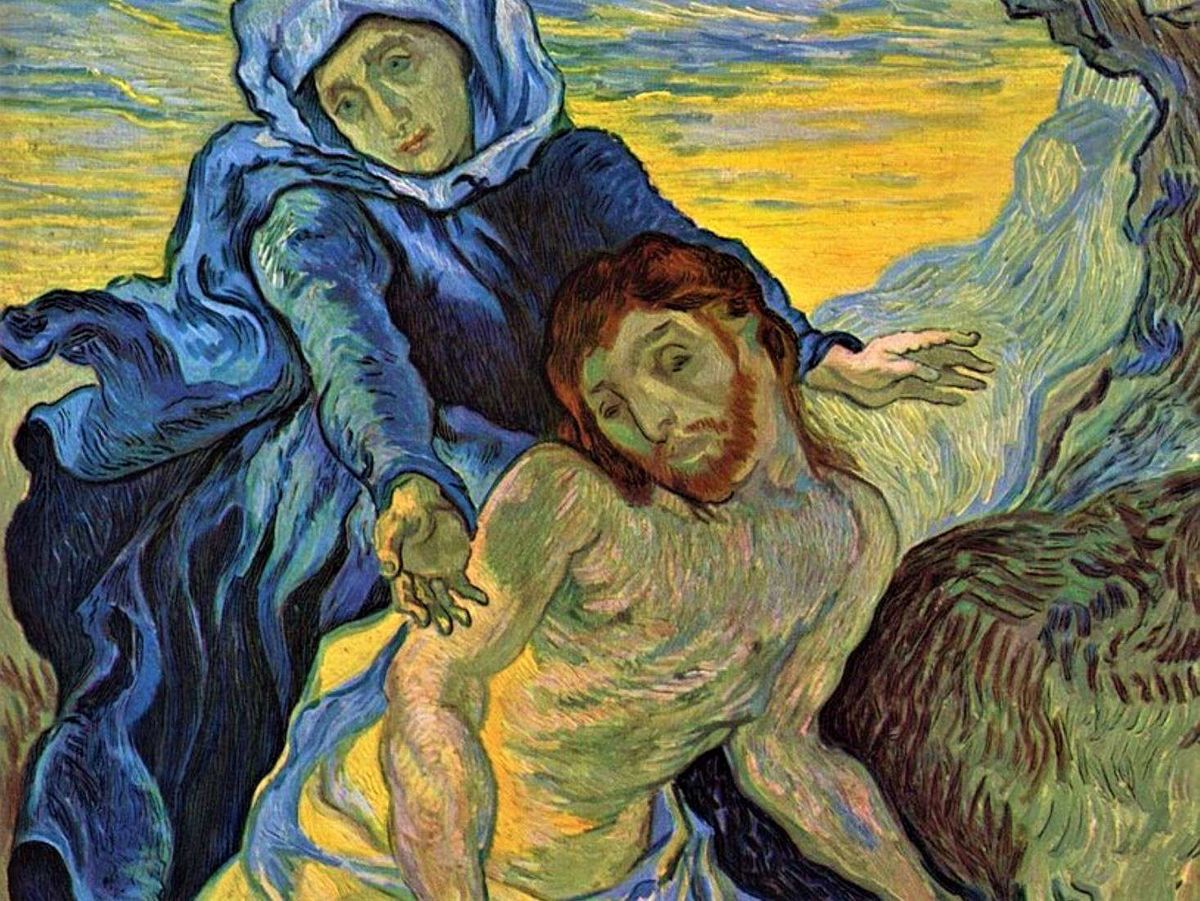

Featured Image: Vincent Van Gogh, Pieta After Delacroix, 1889; Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD-Old-100.