Saint John Henry Newman, one of the greatest modern intellectuals for both Anglican and Roman Catholic traditions alike, had little patience with Romanticism. Although a contemporary of the British Romantics—Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, and Keats—Newman was by and large dismissive of Romantic efforts to turn the world away from an overdependence on reason, which had seeped into modern minds with Kantian ideas and the emergence of German idealist philosophy. Instead, Newman offered a robust recalibration of reason in his Grammar of Assent, The Idea of a University, and various of his Oxford Sermons. Reframing the first question of Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica, Newman enjoined, “Admit a God, and you introduce among the subjects of your knowledge, a fact encompassing, closing in upon, absorbing, every other fact conceivable. How can we investigate any part of any order of Knowledge, and stop short of that which enters into every order?”[1]

Newman’s preoccupation with reason and knowing emerged in response to modern philosophy’s downgrade and dismissal of faith as a matter of personal and non-rational belief. What mattered in this emergent post-Enlightenment world was what could be reasonably secured. Christian faith, for the most part, counted for little. Newman’s reevaluation of reason and its relationship to faith challenged the modern mindset. Through Newman, reason could once again can be an ally for Christians.

Newman’s impact is nowhere more evident than in the celebration of reason that emerges in Church’s reception of the Second Vatican Council. Bl. Pope John Paul II continues Newman’s work of reintegrating reason and Catholicism in an increasingly scientific world in his beloved encyclical Fides et Ratio. “Faith is in a sense an ‘exercise of thought’; and human reason is neither annulled nor debased in assenting to the contents of faith.”[2] As with Newman, reason must not be surrendered if Catholicism is to maintain its vitality and apologetic power. Gaudium et Spes exhorts priests and laity alike “By unremitting study . . . [to] fit themselves to do their part in establishing dialogue with the world and with men of all shades of opinion,”[3] because “the experience of past ages, the progress of the sciences, and the treasures hidden in the various forms of human culture . . . profit the Church, too.”[4] Reason supports, rather than threatens, faith. In this post-conciliar spirit, reason has a vital role to play with respect to the mysteries of faith. Mystery offers a deep wood to continuously explore rather than a puzzle to solve. Priests, theologians, spiritual directors, and parish educators have all taken up the task of connecting the faithful to the riches of their living Christian Tradition.

We might contrast Newman’s approach, and thus better understand its legacy, with a theological voice of only a few years prior, namely, the Lutheran philosopher and theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher. Schleiermacher also had concerns with the modern turn that left increasingly little room for faith. Unlike Newman, however, Schleiermacher embraced Romanticism. We find its impact in his focus on non-rational consciousness and prioritization of the individual’s development of this God-consciousness. His contributions, however, concerned Catholics. Language of God-consciousness built around a feeling of absolute dependence seemed overly individual, even if communally supported by a Church body; overly sentimental, even if feeling was related to the interior make-up of each person; and self-salvific, even if every member turned to Christ as the perfection of what a turn from sin and union with God looks like. Kierkegaard’s radicalization of Romanticism’s contrast of reason and spirit into the idea of faith as a leap into the absurd further concretized Catholic worries.

Even Matthias Scheeben, a Catholic theologian whose emphasis on mystery and a sense of individualized journey to God mirrored some of Schleiermacher’s own Romantic propensities, configured his theology around a centralized and luminous “wonderful harmony” that humans are meant to understand, even if as mystery.[5] Scheeben’s mindset helps us understand Newman’s own as the latter filtered Thomistic knowing through an Augustianian lens of journey and analogy. For Catholics, reason’s rehabilitation became the top priority.

Schleiermacher, Kierkegaard, and Newman, however, had more in common than it might initially seem. Schleiermacher’s work, much like Newman’s, took issue with the modern form of reason, both in terms of its scope and its function. Like fellow Romantics, Schleiermacher worked to recast Christianity such that it could debate and counter the modern turn toward rationalization. Much like Newman, the Romantics took umbrage with the systematic strictures of reason that were overwhelming philosophy and politics in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century. Its members were intent on “moving beyond the limits of a rational culture”[6] that stifled individuality for the sake of states, reduced freedom’s indeterminacy for the sake of historical and scientific progress, and sacrificed creative choice for the security of ethical certainty. In other words, a world in which Kantian thought ended in Hegelian completion was a world that would crush, rather than fulfill, human life. Beginning in Jena through a social circle and journal publication (Athenäum) founded by the Schlegel brothers, Romantic ideas circulated throughout Germany as well as within France and Britain and stood against the continuation of concretized rationalism and the emergence of philosophical idealism.

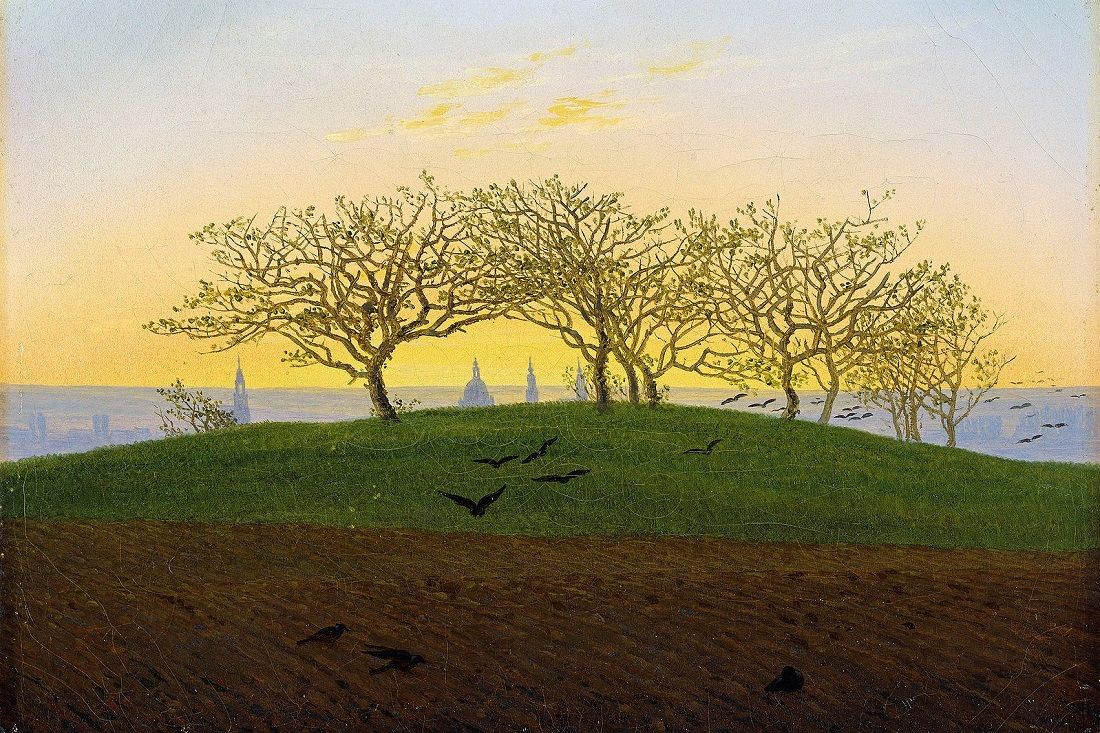

What, then, is Romanticism, and why were Catholics so wary of it? Beyond their differences, Romantics shared many common traits. First and foremost, they concerned themselves with the vitality and incomplete nature of the human spirit. Unlike Hegel’s Geist, whose self-completion was a matter of time and historical progress, the Romantic idea of spirit mirrored much more the journey of Augustine’s restless heart with its press into the infinite that extends ever beyond human achievement. The Romantics saw a non-rationalizable goal beyond themselves that existed within but lay ever beyond human grasp. A preference for night over day was highly symbolic of a path to knowing and existence that presented something beyond the certain confines of Enlightenment thought.[7] The German transition from Goethe and his Faust to Schiller’s aesthetic insights underscores this development in Germany.

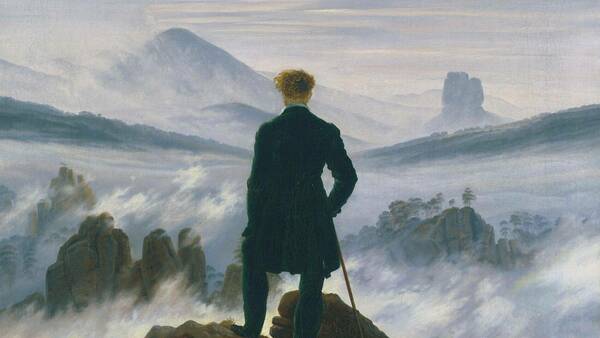

Second, exploration of such potential was determined in large part by resistance of the individual to the crush of homogeneity. Not only was reason a problem for the Romantics, but so too literary and political forces threatened the ability of Romantics to engage what was unique in their own cultural heritage. The German nationalism that developed in Romantic literature united its authors in a stand against French Napoleonic influence. Further, the Romantics were suspicious of political unification that seemed to crush the individual under the weight of the state. Schelling, a former roommate of Hegel, had the latter’s philosophy firmly in his sights as he authored works such as On the Concept of Freedom and Ages of the World. Beyond their political nationalism, these authors made space for the individual and his point of view to stand in contrast to what existed around him. It gave him an imperative to embark on a journey of authentic self-discovery and to legitimate what he found.

Third, Romantics turned to Greek religious thought to recast Christian ideas with an ideal that was as much within the immanent domain of the world as it was out of reach of those who attempted to control it. As in Greek myths, the world of the gods was as closely accessible as it was separate and unreachable for humans to master. Novalis and Hölderlin played with this religiously-inflected “magic idealist vision.”[8] For the Romantics, Christianity’s absolute and infinite sense of the divine expanded Greek divinity and the immanentized idea of spirit such that idealism could not capture and recast spirituality as reason. Joining and redirecting the religious ideas of Greek myth and Christianity was fundamental to the Romantic project of making spirituality central yet beyond human control.

Finally, the Romantics often presented their ideas through poetry, music, and literature in order to express the spiritually incomplete nature of their subject matter. Their melancholic tone cemented their belief that the quest for spiritual depth could not be made into a closed system. The infinite journey of the Romantics was as beautiful and alluring as its lack of reconciliation and final homecoming was a constant source of pain and sorrow. Longing and prayer combine in Hölderlin’s cry “O divine One, be present and more beautiful, as before. O be the one who reconciles!”[9] that signifies as much hope as it does hope’s deferment.

On the one hand, Catholic guardedness with respect to Romanticism is more than warranted. Romantic religious redirection of Christ into the immanent domain of Hellenic mythology excludes Christ as a real savior, and transcendence becomes part of world’s immanent register. The melancholic tenor of hope permanently deferred gives new form to the tragic. The infinite and highly personal spiritual journey in the mode of resistance puts the individual at odds with the Church as communion. There are compelling reasons that Catholics have by and large avoided baptizing Romanticism, and even thinkers as capacious and hospitable as Hans Urs von Balthasar exhibit great caution when approaching the Romantics.

On the other, there is something to be said for the non-rational Romantic approach, and consequently we find its traces in contemporary Catholic thought. Erich Przywara reclaims Hölderlin through claims of a Christocentric core that brings darkness directly to bear on the mysteries of Good Friday. Henri De Lubac investigates the transforming union of humans’ natural spiritual tendencies by the supernatural grace of God. Even von Balthasar cannot resist the potential of lyrical prose in his Heart of the World as an important method of spiritual journeying, nor fail to praise the lyrical mysticism of Scheeben and others in his trilogy. While there exists a healthy amount of reserve that never allows for a full embrace, Catholic theologians in the 20th century open a space for theological engagement with Romanticism. This shadow-side of reason ceaselessly disrupts reason’s totalizing security. It reminds humans of their peculiar position as finite beings who are ordered to an absolute they cannot control. It presses them to recognize the importance of their personal spiritual journey. It unmasks ersatz substitutes such as knowledge or power that modernity might attempt to substitute as the meaning of human spirituality.

We certainly cannot deny that Newman and contemporary expressions of reason make up the front lines in speaking to an increasingly technologically inclined rationalism in the West. Recent encyclicals like Laudato Si’ effect a broad and real hospitality that brings Catholic teachings on the environment into robust dialogue with a diverse range of religions, spiritual approaches, and scientific data. However, as certain theologians seem to sense, there remain lacunae to when regarding and speaking to secular contemporary consciousness. Louis Dupré reminds us in his The Quest of the Absolute that current tendencies toward personally-discovered spiritual identity, unconditioned freedom, and an imperative drive toward creativity all have their roots in Romanticism. As much as the Enlightenment inclination toward reason has cemented certainty in quantifiable scientific output, so too has something of the Romantic disposition taken hold in Western mentalities. To ignore this aspect of Western consciousness comes with an increasing cost. Should reason fail to compel contemporary audiences, even its recalibrated form runs the risk of falling on deaf ears. Moreover, when rational disillusionment surfaces, so too do the latent propensities toward Romantic thought come to the fore. From the political to religious and personal views, contemporary romantic elements shy away from rational discourse and into an increasingly isolated individualism of autonomous creative identity. How is the Church to respond?

I submit that Catholics ought to take on a two-pronged approach to the legacy of Romanticism. In terms of its evangelism, the Church must learn to recognize and speak to the Romantic elements of today’s culture. Not all will be attracted to a faithful presentation that compels with reason’s clarion call. A question of understanding what elements of Catholic Tradition—from Augustine, Pseudo-Dionysius, St. John of the Cross, Mother Theresa and more—can connect with and redirect romantic tendencies is imperative. The more that romantic leanings emerge from the shadows and condition reason’s power in the world at large, the more the Church must be willing and able to present an alternative. Further, the Church ought to revisit the ways Romanticism relates to certain elements at the heart of the Christian faith. While we ought to take caution as did 19th and 20th century theologians when approaching the Romantics as such, the Church must recognize that it too has a vast and largely underdeveloped darkened dimension that, in some ways, mirrors the Romantic preference for night over day.

The cross as a fundamental feature of Christian theology is not new, but its darker, quasi-Romantic ramifications on Christian ethics, ecclesiology, and spiritual devotion need development. Recognition of Romantic parallels in the Church’s exploration of its deposit of faith can offer guidelines that as much reveal the limits of where the Church’s darkened trajectories ought not to go as they reveal the deep riches that the Church still has to explore. While we must not turn Catholics into Romantics, we would do well to recognize the dangers and values of reason’s shadow.

EDITORIAL NOTE: With an eye toward these goals Church Life Journal published an essay on the Polish Romantic heritage of John Paul II.

[1] John Henry Cardinal Newman, The Idea of a University (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1982), 19.

[2] John Paul II, Fides et Ratio: On the Relationship between Faith and Reason (Boston, MA: Daughters of St. Paul, 1998), 58, par. 43.

[3] Second Vatican Council, Gaudium Et Spes (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 39, par. 44.

[4] Ibid., 40, par. 44.

[5] Hans Urs von Balthasar’s praise of Scheeben comes as a result of this inner luminosity, which in the Swiss theologian’s mind places Scheeben far from what Balthasar perceived as the many dangers of Romanticism. Balthasar effusively declares him as “the greatest German theologian to date” (Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord, Vol. 1: Seeing the Form, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, 2nd ed. (San Francisco : New York: Ignatius Press, 2009), 104.) and celebrates Scheeben even as his work appears to others as confusing and devoid of the luminosity that its author purports.

[6] Louis Dupré, The Quest of the Absolute: Birth and Decline of European Romanticism, 1st edition (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2013), 4.

[7] Ibid., 76.

[8] Ibid., 78.

[9] Cited in Ibid., 90.