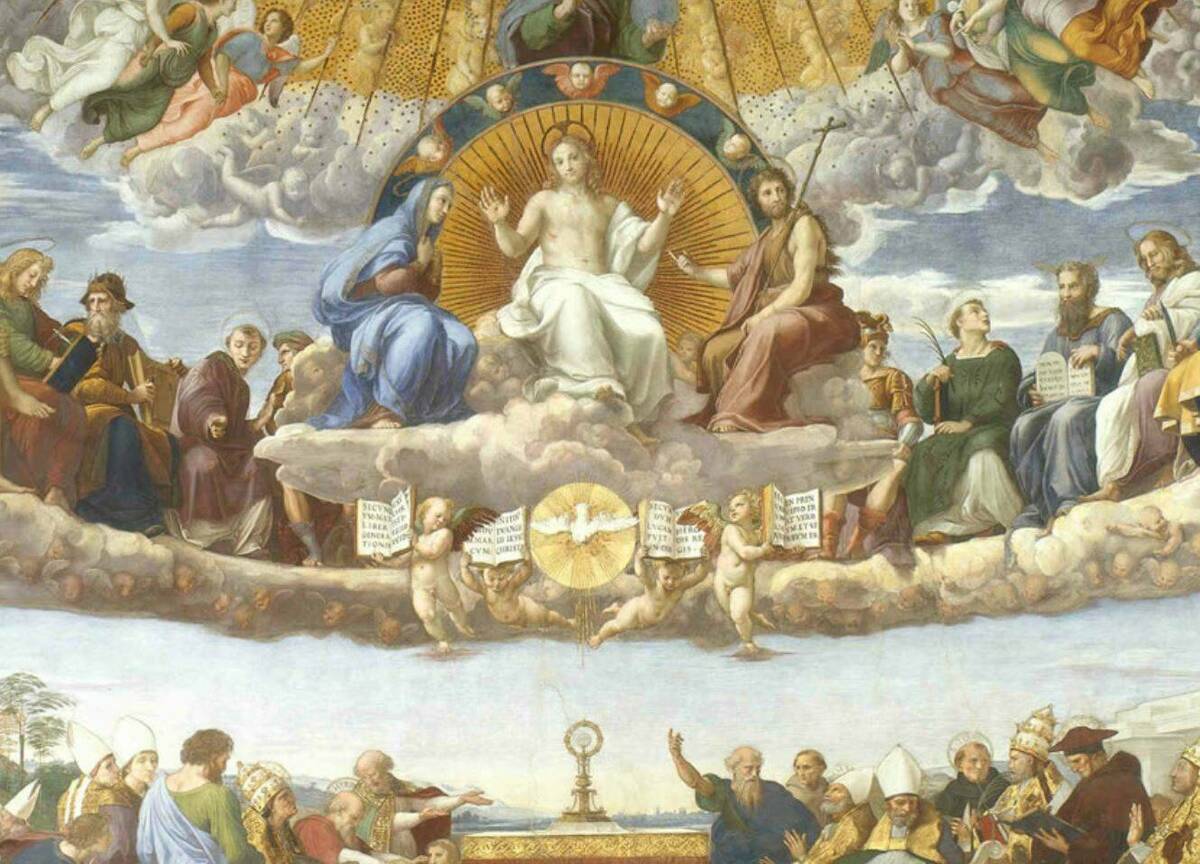

The Church on earth is the visible manifestation of Christ’s love that is enfleshed between each of her members. St. Jerome described this incarnation of love in his famous phrase Corpus Christi ecclesia est, quae vinculo stringitur Caritatis—the Body of Christ is the Church, held together by the bond of charity.[1] Henri de Lubac, the twentieth century French Jesuit theologian, had a profound grasp of this concept.

In my last article I wrote about making deliberate connections between the liturgical action and social action. I argued that true Catholic social teaching cannot begin unless the members of the Mystical Body are divinized or transformed in the love of Christ at the celebration of the Mass. Once this happens, the members of the Church bring Christ’s love into the world and transfigure it into the image of Christ. While the neo-scholastic Dom Virgil Michel, O.S.B. used the theology of St. Thomas Aquinas to make his argument, de Lubac engrossed himself in the Ressourcement, the movement that returned the Church to her Patristic sources. De Lubac was not interested in formulating a new theological method as much as he was concerned for a more visceral relationship between the Mystical Body and each of her members. This relationship, though, is a prime example of the “Catholic Both/And”: the Mystical Body is both a relationship with and between individuals and as a transformed society. And it is in this vein that de Lubac wished to bring the teaching of the early Church into the post-modern era. The Church is a collection of individuals, bound together in the love of Christ, which is his Mystical Body. Each member, then, made in the image of God, is not the subject of an inhuman and faceless social concern.

De Lubac wrote in the first half of the twentieth century, a time when two world wars had fractured the human family to a point where it was virtually unrecognizable. The human family, always a part of God’s plan of salvation, was in desperate need of being refreshed with the breath of the Holy Spirit. Going back to the wisdom of the early Church fathers, de Lubac—along with other theologians of this era—rediscovered the riches of the theology of the Church, or Ecclesiology. It is the Person of Christ as manifested on earth by the Church that will transfigure society into the original form of God’s plan for humankind. As de Lubac said:

Among those who are received within this heavenly city there is a more intimate relationship than subsists among members of a human society, for among them there is not only outward harmony, but true unity.[2]

As grace builds upon nature, so the Mystical Body of Christ cannot exist without sanctifying the whole human family.

What was this to look like practically? For as much as de Lubac wanted the Church to transform the human family through the preaching of the Good News, participation in the liturgical life of the Church was one part of transfiguring society; it also involved ministering to men and women. This ministry, though, was not just about giving food to the hungry and drink to the thirsty, but had to bring together the natural and the supernatural, the worldly and the transcendent. Providing for humanity’s material needs is not enough for de Lubac. As he rightly notes, man is both a body and a soul. Therefore, charity—true Christian charity—cannot be faceless or impersonal. “Charity has not to become inhuman in order to remain supernatural; like the supernatural itself, it can only be understood as incarnate.”[3] So, the social concern of the Mystical Body is not just for the individual, but also for the whole human family; the bodily needs of society and the supernatural pleas of each woman and man.

The Body of Christ is the Church, held together by the bond of charity. It seems like the work of the New Evangelization is progressing, but at times slowly. Like Henri de Lubac, who faced a world with the constant threat of total annihilation, we in the twenty-first century must understand that, as messengers of the Good News of Jesus Christ, we are to be the examples of Christ in our daily lives, fortified through our actual participation in the Eucharistic banquet. Thus made brave, we can divinize the whole human family and each individual through Christ and His Mystical Body.

[1] Henri de Lubac, Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man, trans. Lancelot C. Sheppard and Elizabeth Englund (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 79.

[2] Ibid., 115.

[3] Ibid., 365.