How many times have you said “you” today? Once, I tried to keep track for an entire morning. But during the first conversation, I realized that my pencil could not keep up. I quickly noticed how often I say “you” in a conversation. All the time, my focus shifted to the other person, and I forgot to keep counting. If every “you” was like throwing a ball of yarn that left a thread behind, imagine the web that would form by the end of the day.

The word “you” establishes a connection, no matter the context in which it is spoken. When I say “you,” I am directing attention to someone else, creating a link between us. This can happen intentionally or unintentionally, sometimes even accidentally. The word “you” can also carry negative connotations—it can be hurtful, judgmental, or filled with anger. A “you” can wound us like an arrow. But it can also be a source of love, joy, and connection. So, what does this mean for prayer? What impact does the word “you” have when used in prayer? What does it create, expand, or change? And what would be lost if I stopped using “you” in prayer?

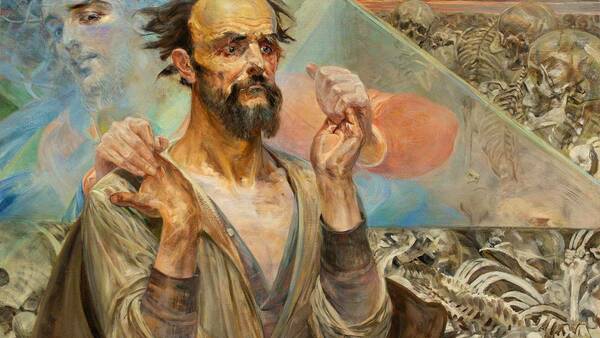

We will explore these questions through a document written 800 years ago by Francis of Assisi. The text Chartula Fr. Leoni data, penned by St. Francis himself, dates back to 17 September 1224, after he received the stigmata. According to legend, Brother Leo was deeply troubled by Francis’ stigmata, prompting Francis to write the autography. The text is both a praise and a blessing, setting a tone very different from the dramatic events on Mount La Verna.

When you read the original Latin, the words “You are” (“Tu es”) pulse twenty-eight times throughout the parchment: “You are humility, you are patience, you are beauty.” This “You” is vibrant, especially since Francis instructed his dear friend, Brother Leo, to keep the writing close, like a second skin. On the back, Francis, according to legend, drew a large red Tau cross with his wounded hands—a symbol closely associated with the Franciscan order. The Tau cross resembles the letter T and every “You are” on the front begins with this symbol. It is as if the Tau cross breathes life into each word.

Considering Francis’s background as a member of the well-known Italian textile merchant family, the Bernardones, I would interpret this “textile gesture” as follows: Francis seeks to clothe Brother Leo with a linguistic garment, woven from qualities like patience, beauty, hope, gentleness, delight, wisdom, and love. However, Francis’s intention goes beyond mere spiritual reflection; he aims to do more than just outwardly clothe Leo. Just as the stigmata marked the skin, this garment is meant to penetrate deeply—but this time without violence or blood. Francis “colors” Leo with this vibrant text, where the countless threads, fibers, and yarns of gentleness, delight, and patience are woven into the fabric of Leo’s very being through the repeated phrase “You are.” It is the “You” that brings the whole experience inward, transforming it into interiority, life, the invisible, and deep pathos. In the rhythmic practice of mumbling, singing, ruminating, and silently wearing this Tau-shaped “You,” God’s presence pulses and breathes within Leo.

In St. Francis’s writings, directly addressing God serves as a powerful connection where God, humanity, and creation are deeply intertwined. This is vividly illustrated in his Canticle of the Sun, composed just weeks after his letter to Brother Leo. Addressing a “you” goes beyond human relationships, a theme echoed centuries later by thinkers like Novalis. Novalis criticized the German Idealists, particularly Fichte, for their emphasis on the “I,” arguing that this focus distorts true identity by separating subject from object. He believed that identity is rooted in a living network of relationships, captured in his formula: “(you.) (Instead of the non-ego: you).”

Novalis lamented the loss of sacredness in modernity and sought to restore it through a renewed vision of nature. In the fragment The Novices of Sais and other sketches, he explores the spiritual growth of individuals seeking meaning in nature, revealing humanity’s deep longing to fully embrace nature as a “you”:

Is it not true that all nature, as well as face and gesture, color and pulse, expresses the emotion of each one of the wonderful higher beings we call men? Does the cliff not become a unique Thou whenever I speak to it? And what am I but the stream, when I look sadly down into its waters and lose my thoughts in its flow? . . . A genuine love for an inanimate thing is certainly conceivable—even for plants, animals, and Nature—and indeed, a love of oneself. Only when a person has a genuine and inward “Thou” does a deeply spiritual and meaningful connection arise, making intense passion possible. Genius may be nothing more than the result of such an inward plurality. The mysteries of this connection are still entirely unknown.

In many religious texts, including Scripture, particularly the Psalms, directly addressing God shows a resonance between the “You” spoken to God and the “you” spoken to others, including inanimate creation, angels, and powers. But how does a simple word like “you” create relationships? Linguistics can help us understand.

On the Exploration of Saying You

Whenever I say “you,” I am directly addressing someone, whether in a conversation, a text message, or even when writing “you” on a wall. This remains true even when it is unclear who exactly “you” refers to. For instance, I might feel personally addressed by an anonymous “you” in a song lyric I hear on the radio. While the song was not specifically recorded for me, the open-ended nature of “you” allows me to interpret it that way. But, how can a stranger suddenly feel like they are addressing me personally?

In addition to the second-person pronoun “you,” our language offers various ways to address someone—by name, through other forms of invocation, using commands, gestures, or even nonverbal cues like a wink. The unique aspect of “you” is its versatility; its meaning changes depending on the situation. Linguists like Émil Benveniste, Karl Bühler, Stephen C. Levinson, and, more recently, Andrea Macrae, Evgenia Iliopoulou, Sandrine Sorlin, and Carrol Clarkson have demonstrated that words like “I,” “you,” “here,” and “now” derive their meaning from the context of the conversation. A “you” shifts in meaning depending on who is speaking and who is being addressed.

Unlike a symbol or image, “you” is like an empty vessel that gains meaning as the conversation unfolds. For “you” to make sense, it must be clear who is speaking and who is being addressed. If this is not clear, as with a song on the radio, “you” gives the listener the freedom to imagine himself as the one being addressed. In semiotics, this feature of “I” and “you” is called personal deixis, meaning these pronouns point from someone in the real world to another person, always within a specific time and place. When it is unclear who “you” refers to, it can create confusion, but it also allows many people to feel personally addressed.

Unconditional You

In prayer, the use of “You” is essential and seems naturally fitting. This is true not only in English, or in monotheistic traditions, but across various languages and religious practices due to the nature of how language functions. In prayer, “You” specifically addresses God, reflecting a deep spiritual connection. This is echoed in the etymology of terms like ad-oratio (meaning “to speak to”) and pro-skynesis (meaning “to kiss toward”). However, “You” in this context goes beyond a mere grammatical function—it conveys spiritual depth and expresses my focused attention on God’s presence, all in a simple and direct manner. In this intimate form of address, there is a profound longing to connect with God, to establish a palpable bond with the divine presence that the “You” in prayer aims to evoke. Every time I say “You” in prayer, I question who I am addressing and what I intend to accomplish with this word. Where am I directing my thoughts? Is prayer creating a real connection, or is it just a reflection of my own thoughts? Does addressing God as “You” signify a true presence that hears and responds to my prayer? Who is this God, and where does God dwell?

Daniel H. Weiss offers a profound perspective for this question: the “You” in prayer is unique because it stands alone, without needing context, specification, or definition. For Weiss, God is simply “You”—a being without gender or boundaries, present even in the deepest suffering, loneliness, and despair. This unconditional “You” is available to everyone, without exception. Weiss argues that the “You” in prayer should remain undefined to fully reveal everything that defines me. The names and titles I use to praise God do not confine God’s “You” to a specific context or specification; instead, in prayer, I express my relationship with God in terms of mercy, goodness, mystery, or infinity—or my longing for these divine attributes.

Weiss emphasizes the distinction between saying “You are patience” and “God is patience” in prayer. The phrase “God is patience” positions God as a distant concept, whereas “You are patience” reflects a direct, personal connection with God’s presence. When I say “You are patience” in prayer, I express my immediate experience: “I stand before you, in a relationship defined by your patience,” or “I stand before you because I need your patience.” Here, the verb “are” separates from “you,” capturing the essence of my present moment and relationship with God.

You, Whom I Do Not Tell (Rilke, Malte Laurids Brigge)

If someone asked me who this “patience” I am referring to is, I would not be able to give a clear answer. I do not know who is on the other end of this relationship. The “You” is simply “you”—close yet indescribable—so I cannot fully explain or identify this “You.” In a way, I am just saying, “Patience, there” or “There is patience standing in relationship with me.” The meaning of my relationship with God unfolds through the qualities that define my encounter with God. It is my experiences, sensory impressions, and perceptions that bring God into the present moment, helping me to find my voice and personal language in the “You.”

At the same time, I can interpret the qualities of God as responses from within me, without claiming to fully grasp or control or own God. Between the World Wars, philosophers Martin Buber, Ferdinand Ebner, and Franz Rosenzweig considered the significance of an unconditional “You.” When we say “You,” we respond to the immediate and innermost presence of God within us and acknowledge our relationship with the divine, even if the “You” remains silent. As Buber articulated in I and Thou, “You” is not something we talk about [Gegenstand]; it is the presence [Gegenwart] itself. By saying “You,” we express the hope and confidence that we can become the “You” for the Other—in essence, becoming the “You” in God’s eyes.

Former UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld also used “you” to address himself in his diaries, published under the title Markings. For example, on Sunday, July 28, 1957, he wrote:

You are not the oil, you are not the air—merely the point of combustion, the flashpoint where the light is born. You are merely the lens in the beam. You can only receive, give, and possess the light as a lens does. If you seek yourself, “your rights,” you prevent the oil and air from meeting in the flame, you rob the lens of its transparency. Sanctity—either to be the Light, or to be self—effaced in the Light, so that it may be born, self—effaced so that it may be focused or spread wider.

Who is speaking here? Is it a soliloquy? Probably not. Yet, it would not be accurate to simply say that God is speaking here, nor would it be correct to say that God is not speaking. The wisdom of the Zen kōan “not one, not two”—an expression meant to transcend rational thought and lead to a direct experience of reality—likely applies. “Patience, there” is itself a kōan.

Leap of faith

A “you” cannot stay fixed; it is dynamic and ever-changing. A variation of the “semiotic triangle,” which explains how signs gain meaning (semiosis), sheds light on the transformative power of saying “you”: the “you” (1) connects the word “you” with (2) the person being addressed, and (3) also intertwines me, the speaker, into this evolving web of meaning. Believing that an unconditional “You” truly exists and holds meaning is an act of faith and reflects a deep longing. As Søren Kierkegaard suggests, every “You” directed to God requires a “leap of faith.” In Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard contrasts the “knight of faith,” who speaks directly to God as “Thou,” with the “knight of resignation,” who addresses God indirectly in the third person.

And if he has perceived this and assured himself that he has not courage to understand it, he will at least have a presentiment of the marvelous glory this knight attains in the fact that he becomes God’s intimate acquaintance, the Lord’s friend, and (to speak quite humanly) that he says “Thou” to God in heaven, whereas even the tragic hero only addresses Him in the third person.

Addressing God as “You” in prayer is a profound act of faith. It acknowledges the presence of a “You” who is universal and ever-present, even before any words are spoken. This “You,” without needing any specific context, carries the fullest essence of faith (fides quae), and the act of speaking it is also an expression of faith (fides qua). The word “you” not only recognizes the reality to which I direct my prayer but also the reality within which my prayer exists. This approach requires minimal theology, resting on the simple belief in God as “You.” Masters of language and seekers of God, like Teresa of Ávila and Etty Hillesum, reveal to us an eroticism of the “you” that conceals as much as it shows, offers a hint of touch, and, in exploring their own desire, suggests the possibility of eye contact where nothing is visibly present. Similarly, contemporary poets such as Mary Oliver, Louise Glück, Alejandra Pizarnik, and Anne Carson express an open longing and invite a continuous search for meaning and connection.

For me, an unconditional “You” that attempts to distinguish itself sharply from the other everyday “you” also harbors a danger. According to Jan and Aleida Assmann, religious speech as a linguistic act characterizes the “radical alterity and difference” of the divine, which is inherent in the world, but qualitatively different from it. The “You” of God can easily be understood here as a “super You” that overshadows all other “yous.” Unlike the many “yous” in the horizontal of everyday life, the “You” prayed for in the vertical touches an unseen world that lies “behind.” Only there does the “real” reveal itself, after a deep change in perception. The “You” to God becomes a self-affirmation and a choice of the praying person. In this context German writer Carl Christian Bry writes in 1925:

Behind your ordinary life and behind the ordinary world lies something that has been hidden until now, something long suspected but never realized by us—a possibility that has never been actualized, which we can now approach, want to approach, and are on the verge of approaching. The follower of a covert religion believes in something behind the world. You might call him a metaphysical “backlander“ . . . For the metaphysical backlander, all things merely serve to confirm his monomania. . . . The world shrinks for the metaphysical backlander. He finds in everything only confirmation of his own opinion. The thing itself no longer seizes him. He can no longer be reached; to the extent that things still matter to him, they are nothing more than keys to the world that lies behind.

If belief in the unconditional “you” only serves to create a self-made world “behind,” then it becomes meaningless and lacks true spirituality. In this scenario, the “behind” and all instances of “you” are consumed by narcissism. As St. Francis’s writings suggest, the “You” to the sovereign God does not lead us into a separate or distant “behind,” but instead reveals our shared, common world.

The intimate connection to the “you” can easily become exclusive and marginalizing, which is why Buber, Ebner, and Rosenzweig emphasize that a healthy I-Thou relationship must remain open and inclusive of others. They even see the act of saying “you” as a way to learn about community and “respons-ability.” Likewise, schools of thought figuring Emmanuel Lévinas, Jacques Derrida, Judith Butler, and Simon Critchley explore similar ideas, focusing on the ethical implications of the “you” in building relationships with others. Since every “you,” even an unconditional one, remains flexible and cannot be permanently fixed, it avoids becoming exclusive. An unconditional “You” stays dynamic, constantly involving other “you,” and is meant to resonate with others on a deep, personal level.

Mister God, This Is Anna

In prayer, the unconditional “You” embraces all others as co-speakers within their own unique contexts. By saying “You,” I am making a promise—a promise that includes everyone: we are all connected in this unconditional “You.” No work expresses this insight more clearly than Mister God, This Is Anna. In the story, five-year-old Anna shares her understanding of the world with the author, Fynn, until she tragically dies at the age of seven. When Fynn visits Anna’s grave, he initially vents his anger at God, but then recalls a conversation with Anna and realizes Anna’s words:

Then you know Mister God in my middle in your middle, and everything you know, every person you know, you know in your middle. Every person and everything you know has got Mister God in his middle, and so you have got his Mister God in you middle too. It’s easy.

This realization brings Fynn new hope—God is in-between myself and in-between all, in everyone’s middle, a part of us, and we are a part of God. The “you” does not retreat into an egotistical “back world”; instead, it illuminates the saying of “you” a million times in everyday life, making them light up. Because the “you” also effects what it signifies—namely, seeing all the “you” before me, beside me, with me, and within me in their mystery without taking away that mystery—there might even be a “sacramental poetics” at work. This does not mean that saying “you” creates or projects the other person, nor is it a special effort or achievement. The unconditional “you” means becoming open to God’s call, vulnerable and exposed, much like St. Francis and Brother Leo. In the search for God, after many years of seeking, there may come one or two little moments when you are gifted with the “you.” Those who have had this experience often find themselves compelled to say, “thank you.” In this moment, the “you” reveals one’s unconditional being—one that is rooted in being an unconditional “you.”

Brother Leo, who was also a calligrapher, outlived Francis by 46 years. Toward the end of his life, he used red ink to write on the document he received from Francis at Mount La Verna, recounting the story of this text that had accompanied him like a garment throughout his life. Leo lived his life in the rhythm of the “you.” Centuries later, Rainer Maria Rilke would capture this same pulse in The Book of Hours when he wrote,

You are, and are, and are. All scales are wrong.

Time flows around you, trembling like a song

…

You, neighbor God, if sometimes in the night

I rouse you with loud knocking, I do so

only because I seldom hear you breathe;

I know: you are alone.

And should you need a drink, no one is there

to reach it to you, groping in the dark.

Always I hearken. Give but a small sign.

I am quite near.

Between us there is but a narrow wall,

and by sheer chance; for it would take

merely a call from your lips or from mine

to break it down,

and that without a sound . . .