I want very much to succeed in the world with what I want to do. I have prayed to You about this with my mind and my nerves on it and strung my nerves into a tension over it and said, “oh God, please,” and “I must,” and “please, please.” I have not asked You, I feel, in the right way. Let me henceforth ask You with resignation—that not being or meant to be a slacking up in prayer but a less frenzied kind, realizing that the frenzy is caused by an eagerness for what I want and not a spiritual trust. I do not wish to presume. I want to love.

—Flannery O’Connor, Prayer Journal

Three summers ago, at the height of the COVID pandemic, I got one of those out-of-the-blue, you-don’t-know-me, but . . . kind of emails that writers either love or hate, from a nun who had read some of my essays on Flannery O’Connor and wondered if I might have time to talk with a film producer who was working on a couple of scripts based on O’Connor’s work.

The producer, Joe, had acquired the film rights to all of O’Connor’s work and also that of Walker Percy and the Inkling Charles Williams. He was looking for readers—people who knew the source texts well enough to offer feedback.

I agreed to a phone call. The nun, Sr. Margaret Kerry, fsp, of Pauline Books and Media, connected us.

On the phone, Joe told me that he felt he had the opportunity to make movies that mattered. After doggedly pursuing the rights to O’Connor’s work he told me how he had toiled several more years to develop screen adaptations of her 1960 novel The Violent Bear It Away and what he described as an “anthology film” based on some of her most loved stories, which had, he mentioned in a casual way, attracted the interest of Ethan Hawke.

After the phone call, Joe emailed me the scripts and slide decks of vision boards, of sorts; photos that conveyed how Joe meant to capture the Southern Gothic vision and look of the films. As compelling and heady as this all was, I had no idea what my role could be in such a project. It all sounded too good to be true, and so I decided it was.

By the summer of 2023, word was spreading that an O’Connor biopic directed by Ethan Hawke, starring his daughter, Maya, was in the works. Partly out of disbelief, and partly out of self-righteous fear that the film would be a gross miscarriage and misrepresentation of O’Connor’s grotesque vision, I remained disdainful and stand-offish towards the whole project. I did Google “Flannery O’Connor Wildcat biopic producer.” Sure enough, there was Joe’s name: “Joe Goodman.” He had done it.

This might seem a big, deflating wind-up to an anecdote whose moral is “always say yes” when a movie producer asks for your feedback on a script garnering interest from a Gen X heartthrob,” or a reminder that self-righteousness and cynicism are states of mind that stand in the way of growth—spiritual, career, or otherwise. But it is really a prelude to a reckoning with what O’Connor considered a mortal enemy of true artistry: that moment when the artist is asked to “represent the country according to survey . . . in order to produce something a little more palatable to the modern temper.”

My aversion to Wildcat grew ever deeper as reviews began to surface in industry journals from critics who happened to catch the film as it slowly slinked its way around the film festival circuit: Toronto, Telluride, and Stockholm. Reading the reviews, I wrinkled my nose and took pleasure in remembering O’Connor’s own indignation at the publishing of a Eudora Welty story in The New Yorker: “All the stupid Yankee liberals,” she wrote to a friend, “smacking their lips over typical life in the dear old dirty Southland.”

It was not until the beginning of November, when a friend sent me a link to an interview with Ethan and Maya Hawke with Bishop Robert Barron, Bishop of the diocese of Winona-Rochester, and founder of Word on Fire Ministries, that I began to warm to at least the idea of it.

In that interview I heard two artists—father and daughter—tussling with O’Connor’s work, taking turns (mostly), though in heated moments interrupting one another, to describe the ways that the stories, novels, letters, and especially her previously unpublished Prayer Journal, inspired them to make this film.

The older Hawke speaks slowly and candidly of his own faith journey, begun as a young man and then never fully realized as acting and stardom consumed his life. The younger, Maya, speaks quickly, often looking downward, her yellow hair partly obscuring her eyes, relating how inspiring O’Connor’s desperate attempts to ask God for support in her artistic ambitions have been for her.

O’Connor prays:

Oh dear God I want to write a novel, a good novel. I want to do this for a good feeling & for a bad one. The bad one is uppermost.

The older Hawke, evoking Aquinas, interrupts Bishop Barron to put O’Connor’s struggle with ambition, and the temerity to announce that one wants to be great, into context: “That’s St. Thomas Aquinas . . . God is telling you who you are by what you love. And in the expression of excellence at [what you love] you do honor to your maker.”

Maya Hawke quickly adds, “And I would only argue that [O’Connor] learned that . . . . And what we try to do in the movie is to try to tell . . . how you learn that.” “But,” she continues, “ambition is wildly discouraged in women. It’s embedded within our relationship with the Divine and it’s embedded within our relationship to society.”

It was this moment in the interview that I stopped the video and opened a new tab. This was not what I had expected. I had expected two Hollywood actors making fools of themselves as they attempted to say profound things. But it became clear that the Hawkes understood that art making is premised more on the mysterious hope and trust of prayer than on the risk-averse calculus of Hollywood hit-making, which is ultimately why that evening, almost three and half years after I spoke with him on the phone, I emailed Joe Goodman to say “Congratulations!” and “I’m sorry.”

What happened next is the stuff of fiction: A movie producer, born and raised in Louisville, and his production partner, born and raised in Poland, rented a truck and drove four hours to northern Indiana to screen the film in a college professor’s home.

The professor took the producers on a tour of the campus, where O’Connor visited on two occasions—once in 1957 and once in 1962—showing them the very classroom where, on her first visit, she read her iconic short story “A Good Man is Hard to Find” (a recording of which exists in the University archives). They then returned to the professor’s house and sat in the living room, gathered around a laptop, to watch Wildcat—effectively making its Midwestern debut.

When it comes to making O’Connor more “palatable to the modern temper,” the last few years have been interesting. In 2020, Paul Elie’s jeremiad in The New Yorker, in which he accused O’Connor of racism and alleged that certain O’Connor scholars are complicit as apologists for her views, created a social media backlash that led to a reassessment of her legacy, calls for her cancellation, and even the removal of her name from a dormitory at a Catholic college in Maryland. It also inspired countless hot takes in defense of O’Connor, some even going so far as to claim that her stories such as “Revelation” are “anti-racist”—a designation that O’Connor would almost certainly have rejected. As Joe logged into his laptop and clicked the triangle at the bottom of the screen to begin playing the film, I wondered: Whose version of O’Connor am I about to see?

Wildcat begins with a black and white film trailer for a sensationally scandalous film about a wayward girl, taken in by a woman and her adult son. What could go wrong? Well, it turns out that this waif is a seductress bent on wrecking this home. The son, who is being hounded by the young vamp, shouts hysterically to his mother, “she’s a nymphomaniac!” to which his mother, preoccupied, leaning over a writing desk attending to correspondence, charitably responds: “That’s just another way that she’s unfortunate.” O’Connor aficionados will recognize the trailer as a punched-up distillation of her story “The Comforts of Home” from her posthumous 1965 collection Everything That Rises Must Converge.

Aside from being a startling and hilarious prologue to the film, the scene cheekily evokes O’Connor’s warnings about the dangers of relativism. Not only is the artist asked to

“produce something more palatable,” but, she continues, “we are asked to form our consciences in the light of statistics, which is to establish the relative as absolute.”

These oft-quoted lines are from her essay “The Fiction Writer and His Country,” written to be delivered as a talk at Notre Dame in April of 1957. She begins by evoking an editorial from Life magazine that asked, “Who speaks for America today?” It is a question, O’Connor suggests, that was not being asked in good faith, nor is it even rhetorical. The author had already made up his mind that it was certainly not American novelists.

O’Connor writes, attempting to convey the “gist” of the author’s critique, that though “this country had enjoyed an unparalleled prosperity . . . producing a nearly classless society” that, “our novelists,” on the contrary, were writing “as if they lived in parking boxes on the edge of the dump while they waited for admission to the poor house.”

Furthering her point, she takes explicit aim in her talk at George Gallup, whose Gallup Organization would go global the following year, and had already begun providing market research to corporations and the film industry, and at Dr. Alfred Kinsey, whose 1948 and 1953 Reports on sexual behavior scandalized polite society. In singling out Gallup and Kinsey, she also means to indict the entire journalistic-entertainment-consumerist-industrial complex, concluding, in the final paragraphs of her talk: “Who speaks for America today? . . . the advertising agencies.”

O’Connor took such precise aim at the conflict between artistic vision and commercial viability, it is difficult for me to view attempts at translating her life and work to the screen with anything but extreme prejudice. But the opening set piece of Wildcat does more than just establish O’Connor’s wry view of the pressures placed on artists to be palatable. It also introduces the film’s main conceit: the nymphomaniac’s name is “Star,” and she is played by the film’s star Maya Hawke. This is the first of many moments in the film where Hawke, the star, also inhabits some of O’Connor’s most beloved and maligned characters.

Even the most casual reader of O’Connor will recognize the name “Star.” June Star is the sassy, disrespectful child in O’Connor’s most famous story “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” “We’ve had an accident! We’ve had an accident” June Star shouts, almost gleefully, when the family’s car careens into a ditch. “But no one’s hurt.” One imagines that this is what has become of June; she survived the run-in with the Misfit only to become a nymphomaniac.

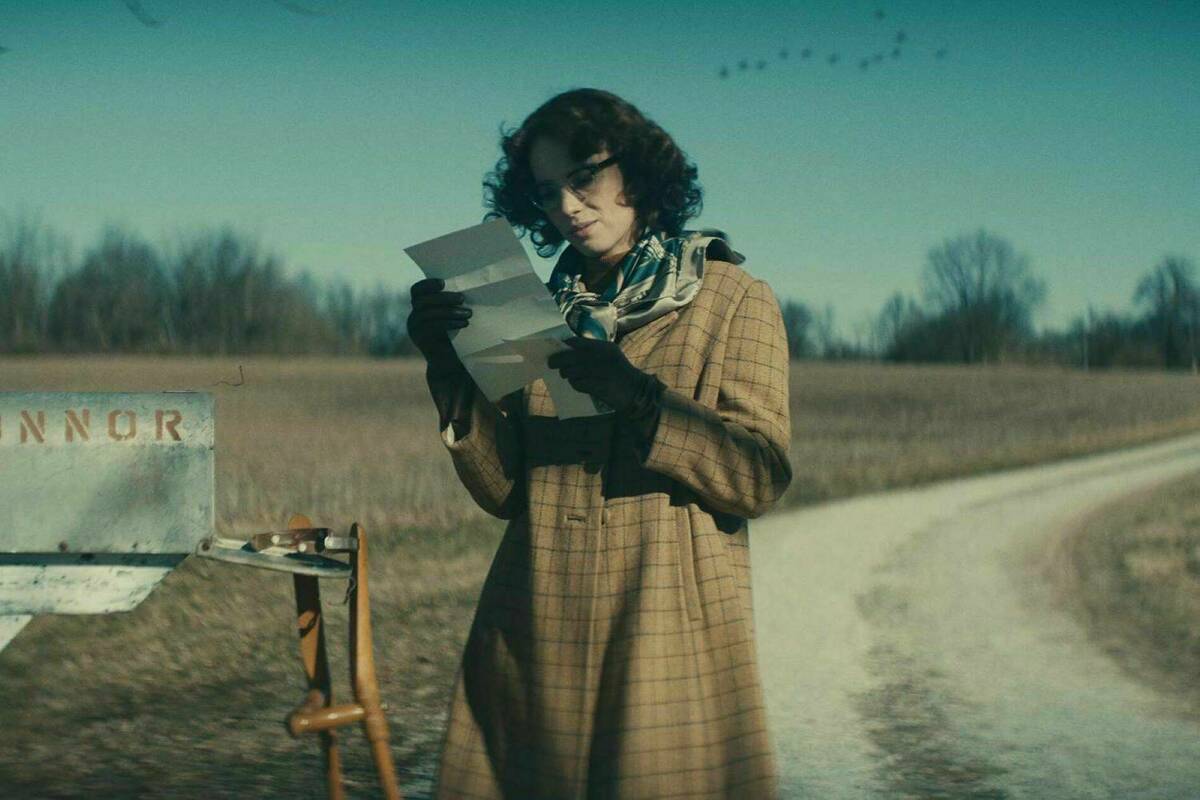

The very next scene begins with just such a tragic accident: we see the interior of a car with a spidered windshield. Someone is trapped inside; we hear their labored breathing. This all feels indebted to the opening of Frederico Fellini’s 8 ½—a desperate, claustrophobic dream suggesting the auteur’s creative and existential dread. And then, just as quickly as we moved from the nymphomaniac film teaser to the wrecked car, we are now with Ms. O’Connor (Maya Hawke) at her typewriter. It is one of the few conventional biopic moments in the film: the writer at her craft in the throes of creation, discovering, it seems by her stunned reaction, bracing herself against the wall of her writing nook, what we feared would happen to the family but dared not think it.

This is the rhythm of Wildcat, absurd then sobering. Patient and subtly drawn moments of human connection between O’Connor and Cal, aka Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Robert Lowell (Phillip Ettinger), are followed by surreal anti-social spasms in which we accompany O’Connor into dark flights of imagination.

Holding the vignettes together are O’Connor’s own words. Both the voice-over narration and dialogue of the film is culled from her fiction, essays, letters, and Prayer Journal. But there is also something painterly in the mise-en-scène. Mr. Shiftlet (Steve Zahn, the one-armed tramp from “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” shambles like Millet’s “Sower” across a barren field onto the property of Ms. Crater (Laura Linney) and her daughter, Lucy Nell (Maya Hawke). There is also something of the documentary photography of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange in the film’s palette and in the composition of shots, and something of Diane Arbus’s carnivalesque photography in the faces of the patients sitting in the doctor’s waiting room when O’Connor imagines the circumstances of her story “Revelation.”

Like that story, which famously ends with Mrs. Turpin (Laura Linney) glimpsing a mystical vision of a “vast horde of souls rumbling toward heaven,” the whole film is a discomfiting visual feast, a cavalcade of grotesqueries tinged with the Gen X angst of its director, Ethan Hawke. But Ms. O’Connor herself is an exception to this. She is not grotesque in the least. In “grotesque works [of fiction],” O’Connor writes, “We find that the writer has made alive some experience which we are not accustomed to observe everyday, or which the ordinary man may never experience in ordinary life.” One of the great virtues of Wildcat is that the young O’Connor is depicted as thoroughly human, not in the comically severe, Edward Gorey style of the photos and illustrations that are popular with some of her fans. Yes, she wears the large, black-rimmed glasses, and, as her health declines, she takes to crutches, but Maya Hawke resists playing O’Connor’s acerbic writerly persona. Instead, she plays her as a reticent, artistically gifted, and devout young woman who is trying to understand her writerly vocation and human desires as much as she is attempting to understand her religious sensibility.

In one scene at a house party hosted by Lowell in Iowa City, O’Connor and Lowell have an awkward flirtation in front of his home. She drops a bottle of wine on the sidewalk, her clumsiness foreshadowing the further discomfort she feels as she tries to socialize with her fellow classmates who drink and smoke and carouse. She ultimately escapes to the bathroom to be sick.

This is not to say that Hawke plays O’Connor as a virgin martyr. In several scenes with Cal, we see glimmers of attraction—a human desire for something beyond being a great writer—not in place of that ambition, but beyond it—only to watch her turn back. This misfit frustration is all masterfully portrayed by Hawke.

The authentically grotesque is rendered, instead, in depictions of bigotry. Case in point: O’Connor’s aunt (Christine Dye), whose assessment of the literary scene in the gallant South is very close to the grandmother’s in “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” “We need more writers like Margaret Mitchell,” she suggests to O’Connor, who has just returned from New York City, where she met with her editor. Which is to say, we need more writers who make reality not just palatable but fanatically, phantasmagorically sentimental. But we know O’Connor’s work was only possible because she resisted the pull to be mannered and sentimental about the South. In “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” Maya Hawke dons a white suit as the smug, progressive, would-be writer son, Julian, accompanying his mother on the city bus to her “reducing class” at the Y. He accompanies her not because she is particularly frail, but because the buses have just been integrated and are thus perceived as dangerous. As the mother, Laura Linney exudes the self-righteous desire to be seen as a good Christian woman, like so many of O’Connor’s matrons.

In the end, it is the rhythmic shuttling back and forth between O’Connor’s narrowing reality—from Milledgeville, to Iowa, to NYC, and back to Milledgeville—and the world of her imagination that makes Wildcat such a powerful testament to artistry.

Though O’Connor is on record saying, in one of her most famously testy and controversial letters, that she thought it best to “observe the traditions of the society that I feed on,” she nonetheless reserved her reverence for the “lonesome place” of being a writer, as Hilton Als writes of in his splendid 2001 New Yorker profile of her.

The pressure, tension, and grotesque, kaleidoscopic gyrations of this lonesome place are all subtly present in Wildcat. Everything from the location scouting (pay particular attention to the variety of hats and her home’s screened in porch) to the sound design (shrieking peacocks and grunting hogs) captures the lonesome milieu of O’Connor’s work in a way no one else has seemed able to.

Even legendary director John Huston’s much-lauded 1979 adaptation of Wise Blood breaks a cardinal rule of O’Connor’s sense of the grotesque: “distort without destroying.” The film’s slack-jawed, comic sensibility has more in common with commercially successful romps like Cannonball Run than an O’Connor novel. You half expect Burt Reynolds to roll up in his Camaro and deliver Hazel Motes’ famous line: “No man with a good car needs to be justified!”

Instead, the Hawkes immerse us in the profound and vulnerable dream state of the writer utterly committed to their craft; that in-between time that Frank Kermode calls aevum—the time of the angels.

For all her struggles with prayer, writing is a ritual that O’Connor gave herself over to. It led her away from the familiar surface of things, deeper into the unseen but no less familiar grotesqueness of her region and her country, and eventually into the essential mysteries and tensions of being human. How does one become a great artist and remain humble? How does one give themselves over to the often dark demands of the imagination and still retain one’s faith? These are the mysteries that O’Connor bumped against, like a boat against its moorings.