After rough treatment at the hands of its “cultured despisers” in the thick of the 20th century, beauty made a steady return to a place of prominence in academic discourse, especially in the field of theology, in the latter part of the 20th and the beginning of the current century.[1] Now a mainstay in theological conversation, the discussion of beauty tends to cluster around the series of issues surrounding beauty’s status as a transcendental and its consequent relation to God, on the one hand, and the beauty of creatures and creaturely making, or aesthetics, on the other. More neglected in this new frenzy of activity are the issues surrounding the individual’s experience of beauty.

It is not difficult to see why this question would be neglected, as it stands under suspicion for its association with unsavory elements of a past intellectual hegemony. After all, ever since Kant we have been taught to ask about questions of beauty by looking internally, to the experiencing subject, and this had the result of reducing beauty to the eye of the beholder.[2] But such an individually indexed beauty is therefore not public and, as importantly, not shared. I may not argue with your assessment of beauty, I can only disagree. And while some room may be left for my eye to become sufficiently conformed to yours that I come to see the very beauty that you yourself see, if I fail in this, there is no recourse left: I must simply dismiss you as odd or deviant, and your judgment of beauty is powerless to correct or instruct me. In such a situation, no objective ground can be given for the beauty of creatures, and it is hard to see how one could speak of transcendental beauty in any meaningful way (for the subjectivization of beauty is its immanentization, and the attribution of immanence of such a sort is not compatible with transcendence). Thus, in many ways, the triumph of the discourse of beauty as a transcendental, which was the condition of the possibility for a theologically robust and non-ironic account of aesthetics, was precisely a triumph over preoccupation with the individual experience of beauty.

However, the rehabilitation of the objective character of beauty and the necessary situation within divine beauty of the both creaturely beauty and the creaturely experience of beauty in no way requires the denial of the latter; rather, it provides at last the means for assessing such experiences, means that render such experiences public (in the sense of being accountable to criteria outside of the individual) and shareable. Now we can answer the hard questions about valid and invalid experiences, we can adjudicate disagreements, and we can instruct and correct deviant sensibilities.

But how is this accomplished? The situation of the individual experience of beauty within transcendent beauty, that is to say, within the divine as beautiful and indeed as Beauty itself, means that the individual experience of beauty must be definitionally bound to transcendent beauty. More specifically, it must be such that the account given of the nature of the experience of beauty make reference to transcendent beauty as a necessary and constitutive ground of the experience. And yet, if the individual experience is not to be reduced to the transcendent ground, which would be to wrest the experience away from the individual, to externalize and universalize it, the transcendent ground cannot be constitutive of the individual experience simply according to its native modalities and characteristics; it must enter into such moments in a vulnerable fashion, subject to the modalities and characteristics of the one experiencing. So far, this accords with what we might expect from a Kantian account; but just as the individual experience cannot be reduced to the transcendent ground if there is to be individual experience, so the transcendent ground cannot be reduced to the individual experience if there is to be a genuine appearing. This is true even when we are speaking of the transcendent ground as appearing, for the divine is powerful enough to speak itself in our context. Even were Kant right to doubt that we have an interpretive key capable of allowing us to transition from the phenomenon to the noumenon (and the analogy of being gives us ground to assert that he was not), the divine still comes with its own interpretive key. If we cannot attain von Balthasar, we can slip no further than Barth.

The experience of the beautiful is therefore controlled by some sense of the divine: it is only because we are not ignorant of the transcendent ground of beauty that we are able to have experiences of beauty. But the encounter with what we find beautiful is not an instance of mistaking a creature for God; rather, it is an instance of being reminded of God. I see the creature as creature and yet refer it to the transcendent ground of beauty of which I am not able to be ignorant by virtue of being myself a creature in ongoing relationship to it. As for the vision of God, that is never without creaturely mediation in this life.

If this is what it is to experience beauty, what response best lines up with the dynamics of the experience to which one is responding, and so best honors the experience and maximally receives the good it represents and offers to the soul? Such a response would need to be controlled by that by which the experience itself is controlled, namely, the transcendent beauty that is called to mind in such moments. What I wish to suggest is that the range of proper responses to this experience is delineated by the fruit of the Spirit described in Galatians 5:22-23, and especially in the first two, love and joy. And while love is worthy of special mention in this connection, it is joy, I will argue, on which the accent falls as the proper response to beauty.

Divine Causality and The Fruit of the Spirit

The fruit of the Spirit are love (agape), joy or delight (chara), peace (eirene), longsuffering (makrothumia, “slow to be aroused to passion”), uprightness or kindness (chrestotes), goodness (agathosune), faith or assurance (pistis), gentleness (praütes, also “that which mollifies”), and self-control (egkrateia). These are produced by the Holy Spirit in distinction and opposition to the works of the flesh, which seek to gratify the self; the fruit of the Spirit, by contrast, are directed at others (love, kindness, gentleness), and yet also gratify the self (joy, peace, assurance). They in fact demonstrate that true self-love corresponds to true love of other, both God and neighbor, by blurring the line between what is for the good of the other and what is for the good of the self.

The fruit of the Spirit are a proleptic possession of blessedness, a form of the life to which we are called that is appropriate for the life we now lead. As proleptic, they are preliminary and not full grown, but they are not partial or incomplete. Proleptic possession is not the possession of a part of something that will come later, but the partial possession of something that remains whole, even under the conditions of prolepsis. Spiritual joy is not partial joy; but my spiritual joy is an imperfect possession of spiritual joy.

This underscores that the fruit of the Spirit are not produced apart from the Spirit: only God can give blessedness to the creature, even in proleptic form. Although one may have joy or peace apart from the Spirit, this is only an analogical imposition; spiritual joy and spiritual peace are of a different quality altogether than joy or peace had apart from the Spirit.

On a larger level, the identification of God with Being itself and thus the appropriation of the transcendental properties of being as Trinitarian properties sets the transcendentals in relation to the fruit of the Spirit, for the transcendentals are now properties of that Spirit that causes the fruit. Indeed, the latter are the effects worked in us by the causality of the transcendental character of God on hearts primed for grace. The Spirit graces by coming personally: that is to say, beauty, truth, and goodness come to us personally, and in so doing excite that range of responses that is described by the fruit of the Spirit.

This is to take the fruit analogy seriously, for the tree does not aim at fruit as the telos: it aims at life, its own and that of others like itself, and in the process of growing to maturity it organically and unselfishly generates that which is required for others like itself; for within every fruit is a seed, or indeed many seeds. Likewise the Spirit aims at life: divine life in the mystery of Trinitarian fecundity and reciprocity, and true spiritual life in the lives of angels and humans. In these latter, it is others like itself at which the Spirit aims; not now consubstantial, as in the Trinitarian persons, but deiform: that is, creatures that become most truly what they are meant to be in imaging the divine in a non-consubstantial way. The spiritual fruit are like seeds that are prerequisites for the possibility of this deiform life.

This is elucidated by the following erroneous concern: if goodness is a transcendental property, is it not improper that it also be named a fruit of the Spirit? Rather, the opposite is the case: the fact that the Spirit aims at the reproduction, according to the appropriate modalities, in the creature of the life that the Spirit shares as divine indicates that the effects of the Spirit’s agency ought to stand in analogical relationship to the conditions of the divine life. In other words, the spiritual life for humans is an analogical expression of the divine life, brought about by participation in the life of the Spirit. And so goodness as a fruit of the Spirit is analogous to the good as a transcendental property of the Spirit, and could only be caused by that Spirit (and again this distances it from merely worldly concepts of goodness, which are only analogical to the analogical spiritual goodness).

Why then are there nine fruit of the Spirit, when we typically only predicate three transcendental properties? Because of the penury of our concepts: the full dynamic range of divine goodness is not adequately imaged in our notion of agathosune. To approach adequacy (and it is only ever an approach, for even in the layering of analogical creaturely concepts to refer to divine realities, a maior dissimilitudo remains) the predication of a variety of terms that combine to give a greater sense of the reality described than any one of them could give on its own is required.

Given all this, it would be proper to wonder whether there are something like appropriations or correlations between the transcendentals and the fruit. Perhaps the first three fruit (love, joy, and peace) are analogical to transcendental beauty, the second triad (longsuffering, uprightness, and goodness) are analogical to goodness, and the third triad (faith, gentleness, and self-control) are analogical to truth. But divine simplicity rules this out: the transcendentals are not self-enclosed, but rather coinhere, as is true of all divine attributes. Although they are conceptually separable, they are still not well conceived as divine so long as they are considered separately. One only first approaches a conception of divine truth when that truth is considered as necessarily good and beautiful. This explains why there is some plausibility in the appropriations I just suggested: any three fruits selected should be explicable as a reasonable triad analogous to any of the transcendentals precisely because all nine fruits are analogous to all three transcendentals. This also explains the feeling that any appropriations are strained, for by artificially selecting only three, one has truncated the full sense of whatever transcendental is under discussion.

This also means that each one of the fruits is related to each of the transcendentals such that peace, for example, is not rightly understood until we understand it as the response not just to the good, but also to the beautiful and the true. This ought to mean that the account offered here of the relation between joy and beauty ought to be repeated for joy and truth and joy and goodness, and this is indeed so: a full account of joy as a human response to the causal influence of the Holy Spirit would need to consider also the dynamics of transcendent truth and goodness. But equally, such an account would not consider joy in isolation from the other fruit. My goal here is to gesture at the fecundity of such an account rather than to provide it.

We may therefore say not improperly that joy is a creaturely modulation of the beauty of God. But we are focused here on the experience of the beautiful, not God as beauty itself. So the dynamic we are interested in is not the way in which the creature expresses a certain deiformity in imitation of the beauty of God, but rather with the fact that the experience of what reminds us of God yields joy as its response.

The Arousal of Joy by Beauty

Before further probing the way beauty arouses joy as its response, we may ask: does joy belong to God in such a way that every experience of joy is to be referenced to God as every experience of the beautiful is to be? My intuition is yes. This is what gives joy its abiding power even in the face of sorrow and tragedy, for joy is rooted in that place where it is known that all things are well, even when things seem to be extremely bad. Absent a transcendent frame of reference, such joy in the face of horrendous evil would be groundless, and nothing less than obscene. But such a transcendent frame of reference, however it may be named by non-theists, is in fact an awareness of God. But even if the answer were no, we would be concerned in this analysis with the type of joy that is to be indexed to God as its ground; that is to say, with the joy that is a fruit of the Spirit.

It may then be asked whether joy has any unique place among the fruit of the Spirit, or whether it is chosen at random. Especially given the claim about simplicity, could we not just as easily speak of kindness or self-control as the proper response to beauty? This would be to claim that the circumincession of the divine transcendentals is mirrored in the fruit of the Spirit. But this claim is not obviously true: creatures (humans, at least) are not simple, and so image the simple God in a complex way. It is true that our imaging of a simple God points in the direction of an explanation for the unity of parts that constitutes creaturely identity, but it is still the case that the image of simplicity manifests as an interrelation of parts rather than as circumincession or coinherence.

Even once the simplicity move has been blocked, however, the question remains. For it remains true that appropriations of particular fruit to particular transcendentals are not to be sought. And is it not an instance of such appropriation to claim that joy is uniquely or specially aroused by beauty?

Here I think it depends greatly on what is meant by “special” or “unique.” If the claim is that joy is aroused by beauty and kindness is not, then this is false. But if the claim is that there is a relationship between joy and beauty that is more richly revelatory than the relation of beauty to the other fruit, I think this is likely to be true, with the exception of love, concerning which will speak later. In this way the claim that it is important to speak of joy in this connection in a way not mirrored in the other fruit is not based upon an exclusive relation of causality between beauty and joy, but rather on a certain suitability of signification between cause and effect in this instance.

We have allowed, then, that beauty does not only arouse joy, though it specially arouses joy. The complementary question must also be asked: does anything besides beauty arouse joy? If the answer is yes, then we ought to ask what the relationship of beauty as catalyst to other things as catalyst is: Is there a larger genus of which beauty’s ability to arouse joy is but a species? Or is beauty unrelated to other ways of approaching joy, such that it has its own special dynamics? But if the answer is no, then it seems that beauty and joy are so tightly linked that one can only come to joy through beauty.

The answer is, I think, a complicated no. For on the one hand, as has been stated, joy must be discussed in connection with all of the transcendental properties of being, that is to say, in relation to all the common properties of divinity; and this would seem to yield the conclusion that the other transcendentals also arouse joy. On the other hand, because of the simplicity of the divine attributes, the transcendentals are conceptually but not really distinct. So even though each of them may be considered a ground of joy, this does not make the ground of joy something other than beauty; rather, that which beauty is, which is also what goodness and truth and whatsoever other transcendentals there are is, this is the ground of joy. That is to say, divinity is the ground of joy.

So when we consider the effect, the simplicity move is blocked because the modality of the effect is complex rather than simple. But when we consider the cause, the simplicity move is required, for the complementary reason. It is relevant, then, that the answer to the question just given trades heavily on God as Beauty Itself. Is the answer affected when we speak not of beauty itself, nor even primarily of the beautiful creature, but rather speak of the experience of the beautiful?

It is perhaps modulated, but the answer must remain similar. For the experience of the beautiful is nothing other than the more or less explicit vision of the beauty of the creature as grounded in the beauty of God. Thus, the beautiful as encountered (whether properly in God or imaged in creatures) arouses joy, and the same may be said for the good as encountered, etc.

As the final preliminary question, it is relevant to ask whether beauty arouses anything other than joy. And here the answer is clearly yes, because the other fruit of the Spirit are not excluded. Are there, though, other less proper but not improper positive responses? Could one, for example, be moved by beauty to happiness as that dim and graceless shadow of the joy that ought properly to come from beauty? In such cases, it is best to say that what beauty is trying to arouse is joy, but that an impediment in the one encountering beauty diminishes this to mere happiness. Thus, what beauty causes, in a strict sense, is joy, but I may be incapable of receiving joy, and so I receive a lesser shadow.

What then is the special relation between beauty and joy? Joy is, like beauty, eruptive: there is a spontaneity to it that is not really the same in any of the other fruit, except love. The combination of immediacy and urgency with which both beauty and joy enter the soul indicates that they are likely generically related.

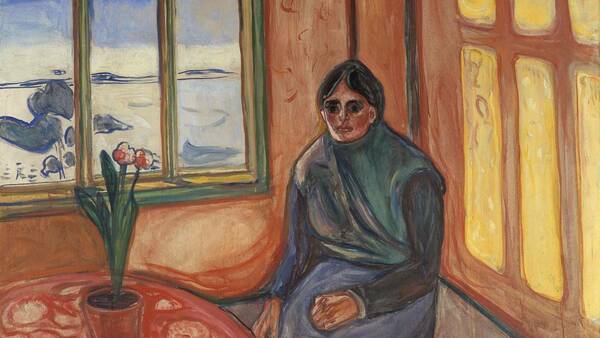

Joy is also, like beauty, not limited to moments absent of suffering, sorrow, or pain. The beautiful is not only capable of shining forth in the darkness, it may itself cast a shadow; and further, may even take darkness into its own depths. It did not take Christianity to make this claim, as mythology is full of dying gods: but the historicity of the dark aspects of the central Christian event (that God is tortured, executed, and buried) proves that it is not merely thinkable that beauty contain darkness, but it is in fact actual. The resurrection that follows and opens the doors of heaven is a demonstration that beauty does not repudiate darkness or unmake it, but rather incorporates it and transforms it. The one seated upon the throne is eternally the lamb who was slain.[3] Likewise joy is compossible with sorrow. We see a poignant example of this in the death of the saints: the faithful who witness the passing of the saint feel both joy and sorrow at once. And this joy is not only for the saint: it is also for our own hope of a comparable death in due course. The pain of loss is real, lasting, and deep; and yet it is not hopeless, for it has a joyful context.

But all of this remains at the level of merely external description. Any answer to the question about the special relation between beauty and joy must arise from the same place as the understanding of beauty. Joy must be related to the moment in which a creature reminds us of God.

Joy is not our recognition that the beautiful creature is like God, joy is what follows upon the recognition of this similarity. When we come across a reminder of our beloved, the feeling of joy that follows is an expression of the desire we have for the beloved. Joy arises in response to the experience of the beautiful as an expression of our delight in God (and chara may be translated “joy” or “delight”). What the Spirit gives us is the delight that ought properly to attend the recognition of the character of God. Joy is a spontaneous praise and an act of worship.

This sheds light on the broken situations in which beauty arouses hatred or disgust: the difference is not in what is perceived when joy is aroused; rather, it is in one’s orientation to that thing. To respond to the experience of beauty in hatred or disgust is to reject the God of whom we are reminded in that moment. It is an act of hostility or rebellion: and as we can discern from Revelation 19:11-21, the opposite of worship is not indifference, but war against God.

Now in this life it is not the case that the saints respond to the experience of beauty in joy and others in hatred or disgust; rather, the saints also respond with hatred or disgust, in that moment revealing the imperfection of their love for and understanding of God. Likewise, others also respond with joy, revealing that they are not entirely haters of God, have not forgotten God, and are not immune to the influence of the Holy Spirit: “The wind blows where it wishes” (Jn 3:8).

Further, that joy must be aroused or awakened in us underscores that however properly we may think of humans as agents (and I wish in no way to reduce our sense of this), we must also be thought to be patients. Joy is not something that one goes to secure for oneself; rather, joy is something one must accept. The experience of joy is thus entangled with our creatureliness, for it is only when we know ourselves as limited and determined by another that we are rightly disposed to receive joy. This is why some sense of transcendence is ineradicable from the experience of joy. Whether directed at the deity or anywhere else, some sense that one is not the whole and that one is a recipient is required for joy to take root. Thus there is a duty to make space within oneself for joy, to prepare the way of the Lord by making straight the ways within oneself so that grace may be received.[4]

Postscript: Beauty, Joy, and Love

Special consideration must be given to love as a fruit of the Spirit because in many ways it overlaps with the account of joy given here. Now, just as when we speak of joy as a fruit of the Spirit we mean spiritual joy, so here we mean spiritual love. This love has God as its beloved in the first instance, for we may also love others with the same love with which we love God. Spiritual love is love aroused and empowered by the Spirit, and the Spirit arouses us to the fulfillment of both of the great commandments, not only the first. Our love of neighbor is nested in our love of God such that the former is also a part of how we love God. Nevertheless, not all of our love for others is part of our love for God: our hearts remain divided in this life.

How then is this love like joy? First, like joy, spiritual love is a response. This is obviously true, for this love is a fruit of the Spirit. But precisely as a fruit of the Spirit it is a gifted response. The capacity to love in the truest sense is one we receive as grace from the Spirit, not one we conjure up from ourselves. This is true even though such love is the highest act of the will: our wills, weakened by sin, require the Spirit’s help to attain their fullness.

Secondly, love is, like joy, eruptive. It has its roots in spontaneity, but not its essence. Love may arise suddenly and sua sponte, but it can only be established by an act of the will. And not just any act, but one that itself requires fortitude and unfolds over time in such a way that it must be continually renewed. Love, as the characteristic and highest act of the will, is the virtue of the will (in both senses of “virtue”).

Thirdly, love, like joy, comes with a combination of immediacy and urgency. It is immediate because, although a may be loved for the sake of b, this is love in a transferred or analogical sense; properly speaking b what is loved. Love is therefore based in an encounter of some sort: one is before (coram) what one loves, even if only in thought. It is urgent because the beloved is often felt to place a demand on us to be loved. We are free not to love, but it may feel like we cannot not love and be true to ourselves.

But love differs from joy above all in this: Joy is a passive response. All I have to do to receive it is to get out of the way, to let it be given. Love begins with a similar offer of a gift, but it requires also that I act: I must respond in order for love to come to be.

Love therefore arises from the same place as joy; it in fact develops from joy. Spiritual joy is the precondition for spiritual love, just as earthly delight is the precondition for earthly love. And it is this that enables us to understand the non-uniqueness of joy in relation to beauty among the fruit of the Spirit: it is non-unique because it is on the way to something like itself but greater than itself. Joy is preparatory for and pointed at love, and it therefore shares its privileged place in relation to beauty with the love that it is always trying to awaken.

And yet joy is not replaced by love. It delivers us to love, but accompanies us along the way, and stays by our side even once we have arrived. Indeed, because joy comes to its fullness only in love, joy is most full when it has reached this end.

Experienced beauty then is the uncompromising and ineradicable witness that God has left of Godself in the world. The universality of the experience (no one has not experienced beauty, however horrific their life has been) and the universal esteem in which it is held (everyone longs for what each one finds beautiful, unless a large amount of sophist-ication has intervened to kill that desire) demonstrates that no human heart is invulnerable to the Holy Spirit. When we accept the experience of beauty on its own terms, we are humbled by the transcendence of which we are reminded, and the Spirit is able to work upon that humility to draw forth joy as our own proper and yet divinely gifted response. When we receive this joy with gratitude, continuing our cooperation with grace, and when we do not resist the implication of the theological anamnesis of the experience of the beautiful, that joy blossoms into love of God and love of the beautiful creature in the light of the God it represents. In this way, grateful being in the world is always yearning towards and calling forth worship.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay was originally entitled, “The Dynamics of Response: The Experience of Beauty and the Fruit of the Spirit,” and was made possible by a grant from the Yale Center for Faith and Culture.

[1] Hans Urs von Balthasar’s work on the importance of theology done in the key of beauty in his The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetic looms large in this regard and stands at the forefront of a more widespread Catholic retrieval. To this we might add the work of Jeremy Begbie on music and Nicholas Wolterstorff on visual art.

[2] Even though such a position is not fair to Kant, who resists such claims in the Critique of Judgment. Nevertheless, his situation of the essential properties of the beautiful in the one judging rather than in the perceived object (and the general distinction of things into noumena and phenomena and the emphasis he places on the latter) had the effect of turning all questions of judgment, especially aesthetic ones, inward.

[3] Rev 5:12-13.

[4] This preparation for grace does not touch upon Pelagian questions, for the grace at issue here is not the grace of salvation, but a grace of knowing and delighting in the Lord.