Among the most intriguing figures in the ancient Greek world are the two pre-Socratic philosophers, Heraclitus and Parmenides. Heraclitus’s famous saying about the impossibility of stepping into the same river twice encapsulates one of his central teachings: The world is always fluctuating and the only constant is change itself. Parmenides, on the other hand, envisioned a world which was equally extreme, though in the opposite respect. For Parmenides, change is impossible. As his disciple Zeno argued, we may imagine ourselves to observe many things—arrows, tortoises, and athletes—undergoing changes. However, reason is more reliable than observation, Parmenides held, and change, which requires things to “pop” spontaneously in and out of existence, is eminently unreasonable. If it is new, where was it before? If it was there before, how is it new?

As bizarre as these outlooks sound, they left an immense impression on the Western world that would follow. The most illustrious ancient Greek philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, each grappled with Parmenides and the possibility of change in their own unique ways. Plato famously distinguished between the immutable realm of the perfect forms and the shadowy, mutable world of matter in which they were reflected. Aristotle grounded himself in the earthly world, analyzing change in the Physics through his famous distinction between substance and accident, as well as that between form and matter. Each philosopher worked diligently to show that change neither undermines all stability and identity, nor entails a disconcerting “popping” in and out of existence. There is no need, according to Aristotle, to choose between persistence and transformation—change, which re-forms something already there, demands both.

Two and a half millennia after Parmenides, we are still grappling with the puzzles and frustrations surrounding change. The Catholic world is no exception. Addressing the possibility of allowing some divorced and civilly remarried Catholics to receive Holy Communion, over which a flurry of heated conversation erupted in the wake of the 2015 Synod of Bishops, Ross Douthat, a Catholic columnist for the New York Times, weighed in with a particularly Parmenidean approach. Warning against a change on the issue, Douthat insisted that doctrine is something over which even the pope himself “ha[s] no power to change.” Other media outlets have occasionally styled Pope Francis in a Heraclitian fashion, leading some readers to think that any and all aspects of Catholicism were up for grabs. Even some Catholic academics seem to operate in this dynamic of a supposed Parmenidean tradition and an allegedly Heraclitean pope. In the wake of Francis’s recent revision to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which now teaches that capital punishment is “inadmissible,” Edward Feser has accused Francis of “contradict[ing] past teaching,” remarking, “The CDF is not Orwell’s Ministry of Truth, and a pope is not Humpty Dumpty, able by fiat to make words mean whatever he wants them to.”

Intense as these recent conversations about change in the Catholic world have been, they are dwarfed in volume by the arguments about change that surround the monumental event half a century ago, the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). A better perspective on the issue of change in the Church can be gained by considering this event and the ways in which the intellectual giants of Catholicism have treated it.

One such giant is Joseph Ratzinger / Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. Some thirty years ago, Cardinal Ratzinger offered a series of interviews which would have a profound impact on how the council was interpreted in the years that followed. In The Ratzinger Report (1985), he juxtaposed two interpretative readings (i.e., “hermeneutics”) of Vatican II: one of “continuity” and one of “rupture.”[1]

Ratzinger identified the latter hermeneutic as the problematic one, and he had two groups in mind as its proponents. First, a group of Catholics led by Abp. Marcel Lefebvre identified the Second Vatican Council as a case of “rupture” and so rejected the council, styling themselves, the Society of St. Pius X (SSPX), as the defenders of orthodoxy against a wayward Church. Forbidden from consecrating their own bishops, the Lefebvrite leaders incurred their own excommunications by disregarding Pope John Paul II’s prohibition and doing so anyway. Second, a more amorphous group of Catholics agreed that the council was an instance of rupture, but instead saw this as a positive thing: in fact, it opened the doors to a new world of previously unthinkable possibilities. Apocryphal stories of “pizza and beer” masses on college campuses fall into this category, as do schismatic groups of Catholics who, likewise ignoring official ecclesial authority, proceeded to ordain their own women priests.

A hermeneutic of continuity, on the other hand, was to be welcomed, according to The Ratzinger Report. Besieged by the chaos provoked by proponents of “rupture,” Ratzinger endorsed the opposite approach, stressing the word continuity as his refrain: “There are no fractures, and there is no break in continuity.”[2] This endorsement of stark continuity has yielded significant portions of the Catholic Church that go so far as to extend Ratzinger’s position to what one might call a Parmenidean hermeneutic of the council: nothing changed at Vatican II, as least as far as official teachings themselves go.

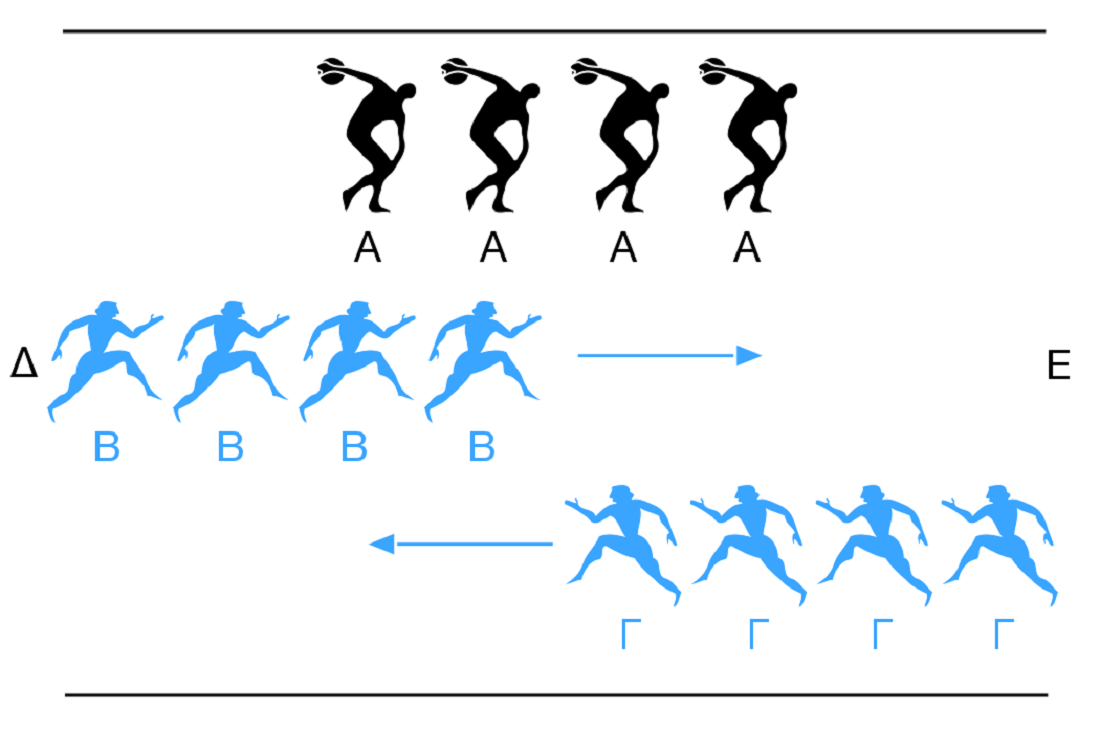

Such an outlook on the past inevitably affects the way one sees the present. After adopting “Church teaching cannot change” as a general rule, processing even modest shifts like Francis’s recent revision to the Catechism on capital punishment becomes exceedingly difficult. Furthermore, I would argue, a bald Parmenidean “nothing changed” hermeneutic of the council functions as the equally problematic counterpart to that of ex nihilo rupture. Not coincidentally, together they represent the two classical extremes offered by Parmenides himself, rejected by the likes of Plato and Aristotle and between which they sought to operate as they constructed their portraits of the world. We can better assess the council, and the Church as a whole, if we operate similarly, refusing to collapse into either extreme and pursuing a responsible way to talk about change.

As it turns out, twenty years after the The Ratzinger Report when he was elected to the papacy in 2005, Ratzinger undertook an important shift in terminology, finessing his preferred language on the topic in precisely this direction. During that first year as Benedict XVI, he explicitly addressed the matter of conciliar hermeneutics, maintaining his earlier claim that one of “rupture” is erroneous. Notably, however, the reading which Benedict approvingly identifies in 2005 is no longer simply “continuity.” He instead endorses what he calls “the hermeneutic of reform.”

I propose that “reform” is the most fruitful way to understand and receive the Second Vatican Council, as well as Pope Francis’s recent and headline-generating shifts.[3] Reform, as Benedict points out, is a “combination of continuity and discontinuity.” It signals a re-shaping of something already there, a “change” in the Aristotelian (rather than Parmenidean) sense of the word. On the one hand, a discontinuity which posits the wholesale introduction of an entirely foreign concept is out of the question. For change to constitute “reform,” discontinuity must be chastened by continuity. On the other hand, a Parmenidean continuity which posits that no meaningful change can occur at all falls short of “reform.” Just as problematic, this is stark immutability. For the Church to be itself, a Church which Pope Francis has described as an ecclesia semper reformanda, continuity must be “enlivened” by discontinuity. In sum, the Church undergoes reform – and its teachings indeed change.

My argument will consist of three components. First, I will comment briefly upon several ways of talking about reform which enjoyed currency during Vatican II, namely, development, aggiornamento, and ressourcement.[4] Next, I will offer a few abbreviated comments on fundamental theology, considering various categories of teachings and levels of authority. Finally, I will consider one of the most salient changes brought about by the council, attending to the elements of continuity and discontinuity which together constitute reform: the teaching on God’s covenantal relationship with the Jewish people, contained in Nostra Aetate.

Kinds of Reform: Three Euphemisms

Due to its connection with the Protestant Reformation, the word “reform” carried a certain stigma for Catholics at the time of the council and so was not frequently used. When it was (e.g. in Yves Congar’s True and False Reform in the Church, 1950), its use was viewed with great suspicion. Even at the council itself, circumlocutions were employed. For example, the “Protestant” phrase ecclesia semper reformanda was transposed in Lumen Gentium, which speaks instead of an “ecclesia . . . semper purificanda” (§8). Several other euphemisms for reform circulated at the time, namely, development, aggiornamento, and ressourcement. An analysis of these terms can give us an idea of how precisely reform, with its elements of continuity and discontinuity, was envisioned at the council.

Vatican II occurred in the midst of a new intellectual climate in the Church, one in which people were keenly aware of being historically-situated. Especially during periods of defensiveness in the wake of the Protestant Reformation and the French Revolution, many Catholics tended to think of religious matters in an ahistorical, timeless sort of way. A Church which identified as the “Guardian of Truth,” regardless of time, age, or culture, carried significant appeal, especially as Catholics came to grips with increasingly daunting challenges in a post-Enlightenment world. Trouble arose, however, when side-by-side comparisons of the Church’s teachings, practices, and liturgies over the centuries showed disparities.

Such disparities were well-noted by John Henry Newman, whose own work on early Christian theology made them rather obvious. Undeniably, the language being utilized by theologians and Church officials in his own day differed greatly from that of the early Church Fathers. Did such a difference delegitimize the authority of those in his own day? Newman’s negative answer was defended in his An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1846). Given the rather ahistorical approach to doctrine at flourishing at the time, Newman’s work, infused as it was with historical awareness, was initially greeted with suspicion by many Catholic authorities in his day. However, Newman’s proposal would gain wide accepted by the time of the council a century later.

Development stands as a kind of reform in the mode of “deepening.” A doctrine which develops is akin to a road being extended through overgrown terrain. It moves forward, enabling the one traveling on it to see new sights and surroundings, but it always proceeds in a consistent direction. A classic example of doctrinal development is Vatican I’s definitions of papal primacy and infallibility. These teachings had never been explicitly defined in the preceding eighteen centuries, nor was this vocabulary used by the Church Fathers. Nonetheless, even in the 100’s CE figures like Ignatius of Antioch and Irenaeus of Lyons speak of the Church of Rome and its bishop (i.e., the pope) in preeminent and authoritative terms.[5] The definitions themselves were understood not as novelties or inventions, but deepening “developments” out of ancient teaching.

As widely accepted as Newman’s teaching on development had become, it never became an explicit object of reflection in the documents of Vatican II. Even so, theologian John Courtney Murray identified development of doctrine as “the issue underlying all issues at the Council.” Indeed, many of the most heated battles at the council were fought over whether a given proposal stood as a legitimate “evolution” or constituted a more radical “revolution.”

A second euphemism for reform was aggiornamento. This Italian word is sometimes translated as “accommodation,” a term which I find less than helpful. It can suggest an uncritical adoption of contemporary trends, which is more a caricature than an indicator of how it was used at the council. A more helpful translation is “updating,” and refers to the Catholic Church’s ability to remain living and adaptable.

If development is like a road being constructed through overgrown terrain, aggiornamento can be thought of as the terrain’s topography that shapes how precisely the road is going to wend and weave or determines the necessity of a building a bridge. In his opening address to the Council, Pope John XXIII encapsulated the notion of aggiornamento: “the Church,” he wrote, “should never depart from the sacred patrimony . . . But at the same time she must ever look to the present, to the new conditions and new forms of life introduced into the modern world that have opened up new avenues to the Catholic apostolate.”[6]

A classic medieval example of aggiornamento is the Eucharistic doctrine of transubstantiation. Of course, the more fundamental doctrine of Real Presence is widely attested to in early Christian literature. The usage of Aristotelian metaphysics, with its notions of substance and accidents, to describe the Real Presence was, however, a case of “updating.” The Catholic Church in the 10th and 11th centuries faced significant debates about how to properly describe the consecrated bread and wine as Jesus’ body and blood. Opinions ranged from extremely “carnal” interpretations to more vague “spiritual” ones. Meanwhile, Islamic scholars had rehabilitated Aristotle’s philosophy and theologians in the Christian West soon followed suit. Aristotle’s philosophical concepts, as trendy as they were precise, were utilized by medieval theologians like Thomas Aquinas to reformulate the ancient doctrine of Real Presence in a way that would address problems and questions that had arisen in the medieval Church. It was not long before this aggiornamento of Eucharistic theology made its way into conciliar teachings themselves.

Finally, ressourcement was used at the time of the council as a way of discussing reform. The term is a French parallel to the Renaissance cry of ad fontes, that is, “Back to the sources!” Instead of looking at current trends or toward “deepenings” that can be explored for the future, this mode of reform looks back to the classics in order to shape the present. At the time of Vatican II, this entailed a renewed examination of patristic and scriptural sources, which frequently received less explicit attention from Catholic theologians than did the work of Thomas Aquinas.

The prominence of Thomas’s thought in the years leading up to Vatican II is itself attributable to a kind of ressourcement. In order to combat the increasing secularism and destabilization which accompanied the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, Pope Leo XIII in 1879 endorsed the thought of Thomas Aquinas as normative for Catholic theology and philosophy. The proposition was that the examination of this 600 year old thinker could bear great fruit for addressing the problems of the present. The result was an appropriation of Aquinas’s thought known as neo-Thomism, a usage of Thomas to remedy the threats of “Modernism” and “Liberalism.” This remedy became ubiquitous throughout Catholic theology but also left some Catholics dissatisfied.

Within a few decades, not a few theologians, especially those in France, undertook an effort to look back still further, turning to the early Church Fathers and the Bible itself, rather than to Thomas, as providing their primary theological lens. Such figures include Henri de Lubac, Jean Daniélou, and Joseph Ratzinger. Ratzinger found the neo-Thomism of his training to be dry and impersonal, focused excessively on concepts. He much preferred the poetic and heartfelt language of early Fathers like Augustine. As one of his seminary instructors explained, Ratzinger was “not interested in defining God by abstract concepts. An abstraction—he once told me—didn’t need a mother.”[7]

Ressourcement was considered with great suspicion by Catholic authorities who privileged neo-Thomist thought. Neo-Thomists referred to the movement pejoratively as la nouvelle théologie, with “novelty” standing as a kind of (Parmenidean) expletive. As traditional as attending to the Fathers and the Bible may sound, ressourcement is in some ways the most radical of these euphemisms for reform. If development is like advancing down a road and aggiornamento functions to shape the road’s specific course, ressourcement means pulling over the car, putting it in reverse, driving to an intersection passed by miles ago, and “developing” from that previous point. Ressourcement does not constitute rupture, based as it is in the Church’s history, but it is radical insofar as it implicitly critiques the path that had been taken. It involves “backing up.” For good reason, it is the most noticeable kind of reform and change.

What Can Reform?

The notions of development, aggiornamento, and ressourcement all indicate some aspect of reform as it was being discussed at the Second Vatican Council. But let us pause briefly before explicitly considering this reform in action. First, we must address an underlying question: What can undergo the process of reform in the first place?

Not all things taught by the Church can be treated under the same rubrics. Various exhortations and pronouncements are made for differing reasons and to accomplish differing goals—some to address challenges specific to a time period, some to govern a particular set of communities, and still others to set boundaries for discussing the eternal nature of God.[8] To conflate authoritative pronouncements of these different varieties would invite confusion on a massive scale.

Among such pronouncements are “practices” and “disciplines.” Clearly, these directives can and do undergo reform. It is commonly known that priestly celibacy was not always practiced in the West—this discipline became widespread beginning in the 4th century, flagged in the 10th century, and was reinvigorated by the reforms of Gregory VII in the 11th century. Moreover, the discipline even today is not uniform, as Eastern Rite Catholics allow for married men to be ordained to the priesthood, whereas this is not typically the case for Latin Rite Roman Catholics. Disciplines surrounding the diaconate have also undergone reform. Early councils and the Bible itself refer to women deacons, and whatever their roles were the discipline was eventually reformed in the West to allow only for male deacons. Eventually, the office of deacon was limited entirely to a temporary stage en route to the priesthood, although the permanent diaconate was restored by reforms made at Vatican II. That disciplines and practices can undergo reform is virtually beyond dispute.

Another category of pronouncements is “doctrine.” From the Latin doctrina (“teaching”), a doctrine is an official teaching of the Church. Among these teachings are those taught in a most solemn and definitive manner, rendering them “infallible” (i.e. protected from error). An even smaller subset of teachings, which stand at the center of Catholic faith and at the top of the hierarchy of truths, are “dogmas.” Such truths emerge from God’s own self-revelation in history and comprise what is traditionally called the “deposit of faith.” As the oft-cited phrase goes, all dogmas are doctrines, but not all doctrines are dogmas. Can doctrines, or even dogmas, undergo reform?

First, all official teachings, even dogmatic ones, can be re-expressed. Language alone requires us to do so. Dogmatic definitions formulated in Greek in the 4th century are translated into vernacular languages and used without a second thought. Amid the roaring debates about “one in being” or “consubstantial” in the Nicene Creed, not many Catholics are pressing for an exclusive use of the original Greek term homoousion. The movement of time and history requires re-expression. Moreover, not only linguistic but conceptual translation is certainly possible, as we saw already with the case of Real Presence and transubstantiation.

Pope John XXIII confirmed the universal possibility of re-expression at the opening of Vatican II. There, he taught, “The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith is one thing, and the formulation in which it is clothed is another.” Unlike early Montanists or even present-day Mormons, the Catholic Church does not believe in ongoing revelation, properly speaking—Jesus Christ was the culmination of God’s revelation, and his early followers, the ones most closely situated to him, were the last to make a normative, scriptural record of it. That said, the Holy Spirit is believed to continually guide the Church as it tries to understand this deposit of faith. The Church can issue official teachings, both fallible and infallible, to clarify, defend, and define aspects of the deposit of faith. Part of that teaching duty includes the obligation to, when necessary, re-express its teachings, even the most fundamental ones. However, the “substance” of such dogmas, according to John XXIII, is a settled matter, based as it is on the self-revelation of God in the one who is “the same yesterday and today and forever” (Heb 13:8). Vatican II itself uses the language of “irreformable” for such infallible teachings (LG §25).

This brings us to our most pressing question: What about doctrines that are not infallibly and solemnly defined? Are they subject not only to re-expression, but to reform as well? Or are they, like dogmas, “irreformable”? To put it bluntly: Can Church teaching change, and in a deep, substantive way?

Perhaps an answer to this sensitive question can be found by looking at history and asking a related one: Has Church teaching so changed? Let us turn to the Second Vatican Council; as we will see, history compels us to answer our question in the affirmative. Doctrines can and do change, not in the mode of “rupture,” but in the mode of “reform.” Such reform can neither be collapsed into an ex nihilo discontinuity nor a Parmenidean continuity, but instead brings something new out of an already present reality by way of development, aggiornamento, and ressourcement.

What Has Reformed?

At the Second Vatican Council, the Church changed. The reform it underwent included changes in practices and disciplines (e.g. the restoration of permanent deacons), as well as the re-expression of early teachings (e.g. speaking of the Church, which St. Paul called the “body of Christ,” as the “sacrament of salvation” (LG §48)). However, the Church changed in deeper ways as well, reforming in the modes discussed above (development, aggiornamento, and ressourcement), so that its teaching or doctrine was both discontinuous and continuous with elements of its past. One prominent example of such change is the Church’s teaching on God’s covenantal relationship with the Jewish people (Nostra Aetate).

In its final form, the declaration Nostra Aetate (1965) addresses the Church’s relationship to numerous religious traditions. In its early stages, however, this document focused on Judaism, in particular. This origin is evident in the promulgated version; its fourth section, dedicated to Judaism, accounts for nearly half of this short declaration’s length. Its tumultuous journey through the council can be traced back to a meeting in 1960 between Pope John XXIII and Jules Isaac, a Jewish historian. In that meeting, Isaac presented his research about the “teaching of contempt,” a phrase he coined to describe the long-held Christian belief that the expulsion of Jews from the Holy Land after Rome’s destruction of the Temple in 70 CE was a punishment visited upon them by God for the crime of “deicide,” that is, killing Jesus, God-incarnate. So pervasive was this belief that the early Christian apologist, Justin Martyr (d. 165 C.E.), theorized that God pre-emptively instituted circumcision for the Jews precisely so that later on the Romans could easily identify and subsequently kill any Jews who returned to the Holy Land.[9] About three months after Isaac’s meeting with John XXIII, the pope assigned Cardinal Augustin Bea to begin work on what would become Nostra Aetate.

The “teaching of contempt” is intimately related to another theory, variously termed “replacement,” “displacement,” or “substitution” theology. According to this theory, God’s covenant with the Jewish people was ended with the Jewish rejection of Jesus; subsequently, God instituted a saving relationship with Christians, replacing his “old” covenant with the “new” covenant. The Church was thus envisioned as the “new Israel,” with the “old Israel” standing as a barren, outmoded relic of a past covenant that has since ceased to exist.

Replacement theology has operated throughout the Church’s history, the early centuries of which are littered with “Contra Judeos” tracts. A few centuries after Justin, John Chrysostom (d. 407) proclaimed that although the “Jews had been called to the adoption of sons, they fell to kinship with dogs,” while the Gentiles (often depicted in Scripture as animals) “r[o]se to the honor of sons… [S]ee how thereafter the order was changed about: they became dogs, and we became the children.”[10] As to the present fate of these Jewish “dogs,” Chrysostom asks, “when God forsakes a people, what hope of salvation is left?”[11]

The displacement motif continued strong into the Middle Ages in theological treatises as well as magisterial statements. One such statement is Pope Eugene IV’s bull at the Council of Florence (1442):

[The Holy Roman Church] firmly believes, professes, and teaches that the matter pertaining to the law of the Old Testament, of the Mosaic law, which are divided into ceremonies, sacred rites, sacrifices, and sacraments, because they were established to signify something in the future, although they were suited for the divine worship at that time, after our Lord’s coming had been signified by them, ceased, and the sacraments of the New Testament began.[12]

Continuing, the statement goes so far as to claim that anyone who undergoes circumcision, at any time and regardless of whether any “hope” is placed in the act, is precluded from eternal salvation. Jews in particular are singled out as “not living within the Catholic Church” and thus “cannot become participants in eternal life.”[13]

More of the same replacement theology appears five hundred years later in Pope Pius XII’s Mystici Corpris (1943). In this encyclical, Pius speaks of the Torah as annulled by the Gospel, echoing ancient Christian articulations of displacement:

By the death of our Redeemer, the New Testament took the place of the Old Law which had been abolished; then the Law of Christ together with its mysteries, enactments, institutions, and sacred rites was ratified for the whole world in the blood of Jesus Christ . . . on the gibbet of His death Jesus made void the Law with its decrees[,] fastened the handwriting of the Old Testament to the Cross, establishing the New Testament in His blood shed for the whole human race. “To such an extent, then,” says St. Leo the Great, speaking of the Cross of our Lord, “was there effected a transfer from the Law to the Gospel, from the Synagogue to the Church . . .” (§29).

Within two decades, however, John XXIII and the bishops gathered at Vatican II undertook a monumental reform in Nostra Aetate, shifting away from concepts like displacement and contempt. Its pithy 4th section on Judaism contains a number of groundbreaking passages. Three, in particular, are remarkable.

First, the Council Fathers depict the Church’s relationship with God as deeply bound to that of the Jewish People, and not by way of displacement. Still referring to Christians as “the people of the new covenant,” the document nevertheless describes “the spiritual ties which link” them “to the stock of Abraham,” noting that the Church “received the revelation of the Old Testament by way of that people.”[14] It continues, citing Paul and explicitly identifying Jesus, the Apostles, and the earliest Christian “pillars” as Jews “according to the flesh” (Rom 9:5). Importantly, the relationship here is not described in terms of temporal succession, but rather as an edifice, foundational parts of which are shared by the Jewish and Christian peoples of God.

Second, the status of the Jewish people vis-à-vis God’s covenant is addressed directly and in positive terms. Again quoting Paul, Nostra Aetate recalls of the Jews, “to them belong the adoption [filiorum, “sonship”], the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the worship and the promises” (Rom 9:4). Rather than dogs who are replaced by children, the Jews are said to possess the status of daughters and sons to whom God has given his promise. The Council Fathers continue their exegesis of Romans by proclaiming that “the apostle Paul maintains that the Jews remain very dear to God, for the sake of the patriarchs, since God does not take back the gifts he bestowed or the choice he made.” Although one could interpret the “gifts” and “choice” of God in a number of ways, most readers have taken them to signal God’s covenant. In 1997, John Paul II took up this point, stating that the Jewish “people has been called and led by God, Creator of heaven and earth. Their existence then is not a mere natural or cultural happening . . . It is a supernatural one. This people continues in spite of everything to be the people of the covenant and, despite human infidelity, the Lord is faithful to his covenant.” More recently, Pope Francis has confirmed this teaching in his Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium (2013), “We hold the Jewish people in special regard because their covenant with God has never been revoked, for ‘the gifts and the call of God are irrevocable’ (Rom 11:29)” (§247). The theme of the ongoing covenant has become so prominent in contemporary teaching on the matter that the most recent document from the Pontifical Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews (CRRJ) bears the title, “The Gifts and Calling of God Are Irrevocable.”

Third, in stark contrast to the portrayal of the Jews as accursed in the classical “teaching of contempt,” the Council Fathers insist, “Although the Church is the new people of God, the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures.” Addressing Jesus’ death, specifically, Nostra Aetate maintains “what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today.”

Certainly, the Parmenidean Catholic would struggle enormously with this case. Indeed, groups like the SSPX reject Nostra Aetate and its post-conciliar magisterial expansions in the name of utter continuity with the past. Their website contains an article stating that the “so-called ‘teaching of contempt’” is “nothing more than the traditional doctrine of the Church” and that “reorienting our sacred doctrine to please non-Catholic religions, as was effected by Vatican II, is criminal.” There is no ignoring the discontinuities. The Jewish people, presented by Justin as cursed (even pre-emptively) by God, are not to be presented as cursed. The idea of the Church displacing Israel has itself been replaced by a deep bond that continues to tie together Christianity and Judaism. The Jews’ covenant went from “abolished” and “void” to “irrevocable.” The Church’s teaching on Judaism undeniably changed.

At the same time, change must be discussed carefully. Is the idea of an irrevocable covenant an ex nihilo innovation? With Nostra Aetate, did the Council Fathers realize the worst nightmares of Parmenides’s contemporary Catholic heirs? Such a suggestion goes too far. As with other doctrinal changes in the Church’s history, the shift occasioned by Nostra Aetate is best understood as “reform.” It is both continuous and discontinuous with earlier teaching, operating by way of development, aggiornamento, and ressourcement.

Among these three, the case for development is the most difficult to make. Remarkably, Nostra Aetate does not contain citations of any Church Fathers, medieval scholars, or recent popes. Unlike other conciliar developments (e.g. on religious liberty in Dignitatis Humanae), it does not have recourse to pervasive theological concepts recognized openly over the centuries—mostly because the Church’s previous teaching on Judaism, tinged as it was by replacement theology, failed to provide much material to work with.

The case for development in Nostra Aetate hinges on the act of ressourcement. Pressed to root their own teaching in the Church’s heritage, the Council Fathers returned repeatedly, as evident above, to Paul’s words in Romans 9–11. There, as Paul struggles to reconcile his gospel of Israel’s redemption in Christ with the fact that so many Jews of his day had not accepted it, lie resources for rethinking the relationship between synagogue and Church nineteen centuries later. These perplexing chapters remain remarkable because Paul does not present a tidy theory of covenant-transfer, nor an irenic proposal for multiple, parallel covenants. He speaks in one breath of Jews who have rejected the Gospel as branches of an olive tree which “were broken off because of their unbelief” (11:20), and in the next insists that “all Israel will be saved” (11:26); of Israel “stumbling” (9:32), but not so as “to fall” (11:11); of Israel as a “disobedient and contrary people” (10:21), but one which God has not rejected (11:1). Paul’s writing here shows his intense struggle as he tries to reconcile his confidence in the truth of the Gospel message, so many individual Jews rejecting it, and his confidence in God’s faithfulness to his promises. In the end, Paul seems to settle on a future, perhaps even eschatological vision of “disobedience” transformed into universal, inclusive mercy (11:32), allowing his own frustrations to transition into praise: “O the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!” (11:33).

On the “replacement theology” model operative for much of Christian history, Paul’s struggle here is difficult to understand, except perhaps as a personal one as he sees “his people” being abandoned. But Paul’s problem is a deeply theological one, and he insists that his people are not being abandoned. A major component of Paul’s difficulties expressed in these chapters is this idea of God’s “irrevocable calling” and eternal faithfulness to his promises. This component seems to have been sorely neglected from Paul’s own day to the time of the council, and Vatican II made a concerted effort to take it seriously once again. Its retrieval in Nostra Aetate stands as one of the most radical in Catholic history, for there the Church shifted into reverse and traveled almost the entire length of the highway to reach this early intersection, by which so many had passed. The development which began from this point is still in its early stages, though impressive efforts to take Paul’s dilemma seriously are producing promising scholarship.[15]

In addition to ressourcement and the development that issued from it, Nostra Aetate is an instance of aggiornamento as well. Especially in the wake of the Shoah, research like Jules Isaac’s, which identified Christian contributions to the anti-Semitism and anti-Judaism which made it possible, forced the Church to rethink old paradigms and practices.[16] Responses include modest reforms under Pius XII (1955) and John XXIII (1959) to the Good Friday prayer for the Jews, as well as major transformations. One case of the latter is Fr. John Oesterreicher, a Jewish convert to Catholicism who in the 1930’s worked ardently to convert other Jews. However, as he contended with anti-Semitism, Oesterreicher underwent a radical shift, eventually speaking in the 1970’s of Christianity and Judaism as “two ways of righteousness” that should coexist and work together toward “God’s perfect reign.”[17] In many ways, Oesterreicher (who contributed key passages to Nostra Aetate) encapsulates a parallel transformation of the larger Church. As the CRRJ observes, “the Catholic Church neither conducts nor supports any specific institutional mission work directed towards Jews,” though it certainly did prior to the council. “In view of the great tragedy of the Shoah,” which has forced us to look at our tradition anew, Christians should “acknowledg[e] that Jews are bearers of God’s Word” (“Gifts and Calling” §40) and await the day “when all peoples will call on God with one voice and ‘serve him shoulder to shoulder’” (NA §4). In (and after) Nostra Aetate, the Church “updated” its teaching in light of contemporary events and discoveries, shaping its ressourcement-driven development so as to accord with the most current research and pressing post-war experiences.

Conclusion

Does the Catholic Church change its teaching? As I have argued, an affirmative answer must be given, although care must be exercised in doing so. First, as John XXIII taught at the opening of Vatican II, all teachings undergo translation and re-expression. But most people with this question ask whether more substantive change can occur. On the one hand, practices such as priestly celibacy, the inclusion of women deacons, and even regulations governing admittance of divorced and remarried Catholics to the Eucharist can and have changed.[18] On the other, solemnly taught dogmatic teachings cannot undergo such reform—anyone anticipating an infallible papal definition adding a fourth person to the Trinity will be sorely disappointed. But between practices and dogmas stand non-definitive official teachings, or doctrines, such as the teaching regarding God’s covenantal relationship with Jews and Christians. This case demonstrates that doctrines, too, can and have undergone substantive reform. In particular, they have changed in the modes of development, ressourcement, and aggiornamento, which rule out both Parmenidean stability and the Parmenidean specter of ex nihilo innovation. Reform of these modes does not come “out of nothing,” but instead grows from deep roots in the Christian tradition, sending forth shoots that develop across the surrounding terrain.

Much is at stake in whether one recognizes the reality of such change in the Church. For as strange and eccentric as a figure like Parmenides sounds, there is something alluring and comforting about utter stability. The idea of an immutable Church certainly boasts great appeal for many Catholics. Perhaps especially in the wake of the Protestant Reformation and Enlightenment periods, but today too, steadfast continuity with the past has been hailed as a point of pride among Catholics, one which wards off sometimes disturbing innovations. But two major problems face traditionalist Catholics who collapse into a kind of Parmenidean Catholicism that denies any possibility of doctrinal change. First, they risk rendering the Church an ahistorical, pseudo-Gnostic caricature of itself, an entity divorced from the world. As Newman wrote in his An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, “In a higher world it is otherwise, but here below to live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.”[19] Indeed, to embrace such a caricature can even be idolatrous.

Second, the Parmenidean Catholic who professes an immutable Church will have a very difficult time when faced the Church’s actual history. Cases like those explored here and other historical examples—such as the Church’s teaching on penance, usury, religious liberty, divorce, and slavery[20]—can provoke two frequent reactions, both of which are tragic. The first is to double down on the commitment to an immutable Church in a sectarian fashion, even at the cost of losing full communion with the Catholic Church. Such is the route of the SSPX, whose rejection of these Vatican II teachings, as we have seen, has deeply Parmenidean motivations. The second reaction is to simply abandon the faith altogether, having discovered that a Church advertised as a rock-solid, immutable bastion of sameness in a fickle world is not as promised. Both reactions, I suspect, stand as risks for many ardent Catholics, especially converts and those of a younger generation, for some of whom pre-conciliar theology, liturgy, and rhetoric are enjoying a resurgence. The more we recognize that the Church does not officially and should not unofficially advertise itself in such a Parmenidean way, the healthier, more historically grounded, and more unified the Church will be.

[1] Ratzinger notes a tendency “(to the ‘right’ and ‘left’ alike) to view Vatican II as a ‘break’ and an abandonment of the tradition. There is, instead, a continuity.” Joseph Ratzinger and Vittorio Messori, The Ratzinger Report: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1985), 31.

[2] Ibid. 35.

[3] See John O’Malley, “‘The Hermeneutic of Reform’: A Historical Analysis,” Theological Studies 73.3 (2012): 517–546, as well as Gerald O’Collins, “Does Vatican II Represent Continuity or Discontinuity?” Theological Studies 73.4 (2012): 768–794.

[4] John O’Malley has written extensively about the importance of these three categories at Vatican II; See: “The Hermeneutic of Reform,” op. cit. and What Happened at Vatican II (Boston: Harvard, 2008), 36–43.

[5] Ignatius, Letter to the Romans, pref.; Irenaeus, Against Heresies III.3.2.

[6] Gaudet Mater Ecclesia (11 October 1962), qtd. in O’Malley, What Happened at Vatican II, 38.

[7] Tracey Rowland, Ratzinger’s Faith: The Theology of Pope Benedict XVI (Oxford U.P., 2008), 2–3.

[8] For a breakdown of the various levels of church teaching, see Richard Gaillardetz, By What Authority? A Primer on Scripture, the Magisterium, and the Sense of the Faithful (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 2003), 90–103.

[9] Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho ch. 16, 19, and 92.

[10] John Chrysostom, Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, trans. Paul Harkins (Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1979), “Discourse I,” II.1–2.

[11] Ibid., III.1.

[12] Heinrich Denzinger, The Sources of Catholic Dogma, trans. Roy J. Deferrari (Fitzwilliam, NH: Loreto, 2001), §712.

[13] Denzginer §712–14.

[14] English translations of Vatican II documents are taken from Austin Flannery (ed.), Vatican Council II: The Basic Sixteen Documents (Northport, NY: Costello, 1996).

[15] E.g., Philip Cunningham et al (eds.), Christ Jesus and the Jewish People Today: New Explorations of Theological Interpretations (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2011).

[16] Jacob Marcus offered detailed historical accounts of blood libel accusations leveled by Christians against Jewish communities, frequently with lethal results, in his The Jew in the Medieval World: A Source Book, 315–1791 (Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1938).

[17] John Oesterreicher, The Rediscovery of Judaism: A Re-Examination of The Conciliar Statement on the Jews (Institute of Judeo-Christian Studies, 1970), 56. See John Connelly, From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933–1965 (Boston: Harvard, 2012).

[18] Notably, in 1981 Pope John Paul II explicitly identified the prohibition of divorced and remarried Catholics from Holy Communion as a “practice” in Familiaris Consortio §84. Of course, a practice governing admittance to the Eucharist can involve doctrines, e.g. the indissolubility of marriage, adultery as a grave matter, the three components to mortal sin (grave matter, full knowledge, full consent), and the need to receive the Eucharist in a state of grace. Nevertheless, a change in practice need not involve substantive reform of these teachings. In Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis instead seems to explore the possibility of admitting some divorced and remarried Catholics to the Eucharist by way of close examination of culpability, working within the boundaries of these doctrines to determine whether, in a particular case, a person “fully consented” to their irregular situation and thus satisfies the criteria for mortal sin that would preclude him or her from receiving.

[19] John Henry Newman, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (South Bend, IN: Notre Dame, 1994), 41.

[20] Several examples are addressed in John Noonan’s A Church That Can and Cannot Change: The Development of Catholic Moral Teaching (South Bend, IN: Notre Dame, 2005).