At Jasna Góra

There is David’s Ladder which

Angels ascend and descend

Holy envoys, reconciling man,

With God.[1]

Watching my three daughters during the Christmas season is not exactly a tranquil experience. What begins with an honest and innocent desire to play and re-tell the Christmas story using Playmobil or Fontanini nativity figurines ends up in a squabble over who gets to hold the kitschy statue of Mary and play with her (detachable!) veil, resulting in looks of self-satisfaction in the one who in the end possesses Mary, and tragic resentment on the part of those who are stuck with a dinky shepherd instead. Like my girls, I have been fascinated by this woman since my childhood. She has beckoned and drawn me, and waited for me, wherever it is that she has led me. When I encountered her in her home on Jasna Gora in Częstochowa at the age of nine, I knew she was my queen, my mother, my protectress, my patroness, and my advocate. But I did not know why.

I found myself (through coercion or coincidence) processing on my knees, rosary in hand, beneath the crutch and cane-laden pillars of votive offerings. Surrounded by multitudes of sick and healthy, young and old, jammed and immobilized between a host of drab and gray mohair beret wearing ladies (whose prayers keep the world turning). I was but one small child in this genuflecting procession of her children. I moved with aching knees along the smooth rock floor, worn down through centuries of pilgrims’ knees, entering into her chapel, circling into the reredos and behind her altar, and back out again. It was as if I had been invited into the holy of holies, the culmination of this pilgrimage to the altar of the fatherland, where our “salvation is professed in words and images.”[2] In this heart of Poland, I encountered the essence of Polish Catholicism: the possibility of being confident in God’s merciful providence despite, and in the midst of, suffering.

Both this image and this place, the throne of Our Lady in the heart of Poland, has played a major role in the history of Poland and the modern Roman Catholic Church. Perhaps most famously, the monastery remained the only undefeated place in the Swedish-Polish Wars, and it was during the siege of 1655 when, outnumbered by Swedes and German mercenaries, the Prior of the monastery, Augustyn Kordecki, resisted and battled the invaders who sought to loot the monastery and its most famous image. This resistance, by some accounts, turned the tide of the wars, and was later famously depicted by Nobel Prize-winning novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz in The Deluge.

In more recent times, the image of the Black Madonna was “arrested” by the communist authorities. This act led the faithful to hold pilgrimages and processions carrying an empty picture frame instead, thus expressing the faith of the people despite the image’s absence. The Black Madonna has always stood as Queen and suffering Mother for millions of Poles, wherever they have found themselves. Her role led Saint John Paul II to claim, “There would not have been this Polish pope upon Saint Peter’s Chair without Jasna Góra,”[3] and Pope Francis recently approved the degree of heroic virtue for venerable Stefan Cardinal Wyszynski, who celebrated his first solemn Mass in the chapel of Our Lady of Częstochowa, two years prior to the communist takeover of Poland—not long before Wyszynski’s own arrest and persecution by the authorities.

Like these saints, and the millions of unknown pilgrims whom she has drawn to herself, she continued to lead me in a significant way as an indecisive high school student. Later, I realized that it was not a coincidence that I encountered her in a small side chapel of a basilica on a college campus, as I began college there on her feast day. Like she does for the shepherds, the Magi, and the nameless figures in Bethlehem, she has always led me closer to her Son.

This lady, the Black Madonna, is not only the Queen of Poland or Queen of the Slavs; she is my Queen. Mary reveals a Queenship of suffering love; she is the Lady who will accompany and lullaby her baby from the time he would peacefully sleep in the wood of the manger, until she watched him sleep the sleep of death on the wood of the cross. And this is who she is for the Church: a Queen adorned in regal blue and gold, who stands at the right hand of God in glory, while still quietly hushing and comforting her little children amidst their sorrows and afflictions in this valley of tears.

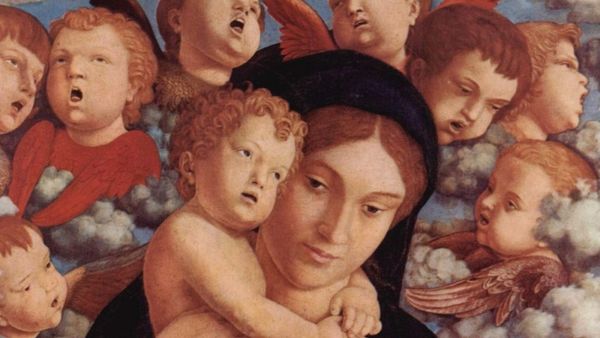

Looking at her image, we see Mary as the one who, by virtue of the merits of this newborn babe, offers the sacrifice of her life in the obedience of faith, always pointing us to her baby King. She both shares some things in common with the iconographic tradition of the East, yet is strikingly different.

She is not surrounded by the brilliant gold of the Byzantine saint who stands in glory, having won the race and conquered over sin and death through a life of ascesis and mortification; we see a Queen who continues to suffer with us, and to accompany us on our journey of self-denial and death, preparing in our hearts a home for the baby Jesus, which can only occur if we empty them of our constructed selves.

In this image of Our Lady, we see the restoration of the image of humanity, which cannot happen apart from an encounter with the newborn babe. Mary is presented as our Queen, the Mother of God, the one who was chosen by God, yet who in the great mystery of divine-human cooperation, still freely chose to be the mother of her Lord. Pilgrims who venerate this icon in the heart of central Europe, “seek and find in it . . . the presence of a complete secret, as if the heavenly king, through the veneration of his art, has really taken up his seat in Jasna Góra.”[4]

In the image, where millions are drawn by the lady and Queen to a path of encounter with her Son, we see that the colors are not arbitrary; they express profound truths.[5] The centrally important aspect of the image is Mary’s face; the large size of the face and the “hieratic upright pose of the Virgin” is unusual to medieval western art thus suggesting an affinity to the Christian East.[6] Following iconographic tradition, the overall aspect of the body’s anatomy is subordinated to the head.[7] Her face is painted using gray or black pigment, which is highlighted with yellow ochre, mixed with red. Her face has a dark, almost earth-like color, and it shares the color of Christ, the New Adam—from the Hebrew adamah, meaning earth—who belongs to all of humanity.[8] The face of Mary, with its dark complexion of earthy colors illustrates her role as the New Eve, the Mother of the Church, and the Mother of all the living.[9] She is part of creation, yet she is an exemplar of the New Creation worked by the Father in Christ the New Adam; her womb was the fertile soil for the seed of the Word of God. Central to the dark face of Mary is the depiction of her eyes. The eyes of the Virgin, the same eyes which gazed upon the infant in swaddling clothes, witness the New Creation of all humanity.

Central to her face are the mysterious eyes, which are said to be the windows to the soul, and are “large and animated” since she has allowed Divine truths to penetrate her being. This iconographic feature witnesses to Ps. 25:15, “My eyes gaze continually at the Lord,” and the Canticle of Simeon, “for my eyes have seen your salvation” (Lk. 2:30). By gazing at the eyes of Mary, we are directed to contemplate the saving work of God in the Incarnation, which is the point of our pilgrimage, whether to Bethlehem, Częstochowa, or a roadside shrine. The Polish chronicler-priest Jan Długosz (1415-1480) writes of the chapel of the Black Madonna in his Register of the Diocese of Kraków:

A chapel of stone . . . in which is displayed the image of the most glorious and excellent Virgin, lady Mary, Our Queen and Queen of the world, worked with astonishing and remarkable painting, having a gentle aspect whichever way you turn, which is said to have been taken from among those which Saint Luke the Evangelist painted with his own hand . . . and if you filled it with singular devotion, you would see it looking at you as if alive.[10]

In the eyes of the Black Madonna, we perceive a tender and loving gaze, which seems to follow us, and draws us to contemplate the beauty and mystery of divine life. While revealing her contemplation of the works and wonders of the Creator, Mary’s eyes also reveal her compassion, compunction, and co-suffering with Christ. For an encounter with the Mother and the newborn Christ—homeless, poor, radically dependent and vulnerable—is an encounter with suffering.

So while we contemplate in Bethlehem the wonders of God in baby Jesus, and in our Mother, our Queen (and poor Saint Joseph, who, as is often his lot, will be ignored here), we remember that this newborn babe will suffer and die for our sins. Mary is a Virgin Queen and Mother, our Immaculata (as St. Maximilian Kolbe called her), created anew in Christ; yet she is one who continues to suffer with her children. Mary’s eyes contemplate the divine glory, both in Bethlehem in her son, and in heaven where she reigns as Queen; yet perhaps Our Lady of Częstochowa, like few other images, reveals the sorrows she, and we like her, must endure. Her eyes are heavy with the sorrows of her earthly life. Mary knows true suffering, and the icon reminds us of this fact in the most striking feature of her face: the curious and mysterious scar on her cheek.

Many theories have been proposed as to the origin of this scar. According to one legend, on April 16th, 1430, debt-ridden Polish nobles recruited Bohemian and Moravian robbers to loot the monastery, at which point the Bohemians “stripped the image of the most glorious Lady of the gold and gems with which it had been clothed by the devotion of the faithful. Not content with stripping it, they disfigured the countenance crosswise with a sword and damaged the panel to which the image adhered, so that not Poles but Bohemians might be condemned for these evil and cruel deeds.”[11] Modern x-ray imagery concludes that the scars are indeed an incision into the wood of the panels. According to tradition, paint was applied to the scars by painters in Kraków who sought to restore the image after its destruction. However, the day after the conclusion of the restoration, the newly-applied paint ran down, and when the workers carried out the work again the same thing happened. The king is then said to have summoned painters with “imperial letters” but their work was equally fruitless and the king relented and acknowledged the miracle.[12] Whatever the actual origin of the scars their presence is associated with mystery and miracle.

Mary’s scars unite her to her newborn King, and to all of us. Although her transfigured eyes contemplate the presence of God, she turns her compassionate gaze towards us. She will suffer the pains of Christ’s Passion, as a true mother who is exposed to the brutal murder of her child. The scars are a visual reminder of her seven sorrows.[13] The penetrating gaze of the eyes invites the viewer to unite her own sufferings to the sufferings of Christ, through the mediation of Mary.

Yet Mary’s contemplative stance also reminds the viewer of the deeper logic of Creation. The created world, fallen through the disobedience of humanity, has been redeemed by Christ, the New Adam, in the order of transfiguring grace. Human senses are raised to contemplation of the divine. Mary’s wound reveals her understanding of suffering, but invites the viewer to remember that suffering is redeemed by a suffering redeemer.

Beneath her eyes, we see her long and thin nose. In the iconographic tradition, this traditional depiction shows us that she does not “smell the things of this world, but the smell of spiritual fragrance, the fragrance of the Holy Trinity."[14] Thus, the long nose lends nobility to the face, and shows that the saint smells the “sweet odor of Christ and the life-giving breath of the Spirit.”[15] The lips of the mouth remain tightly closed, revealing that true contemplation requires silence. This silence of the contemplation of God is a result of a pure soul. The soul has been cleansed through fasting. The closed mouth depicts the ascetic and her limitation to only the necessary food.[16] The body no longer needs earthly food, since it has been transfigured by the grace of God, and the saint is sustained by the sweetness and plentitude of God. Thus, the subdued sense organs of an icon depict the glorified humanity of the saint. Having been freed from the necessities of earthly sustenance, Mary is nourished by the very life of the Trinitarian God. Nevertheless, she identifies with suffering and sorrow, since she herself has experienced it, and through it, come to be glorified by God.

Her humanity has been transformed. The world of the physical senses and sensuality has been subordinated to the “spiritual senses” that perceive the wonder and glory of God. Mary’s penetrating eyes, her elongated nose, and her tightly closed lips express “the infinite peace and freedom” of the Holy Spirit.[17] The viewer is reminded through his or her encounter with the icon of the transformation and sanctification of earthly realities by Christ, who in his Incarnation restores that which had been fallen. The world was given new meaning, and earthly realities are seen in light of their final destiny. The Mary who has been glorified through the grace of the Incarnation stands as a sign of the life of the world to come.

Thus, in Mary:

The eschaton is realized in a created person before the end of the world, [and] henceforth places her beyond death, beyond the resurrection, and beyond the Last Judgment. She participates in the glory of her Son, reigns with Him, presides at His side over the destinies of the Church and of the world which unfold in time.[18]

Mary reminds us that human nature is not bound to sin and death. Like Mary, each human being can be transformed by the graces of the Incarnation into a new creature. The world has been redeemed from the cosmic forces of sin and darkness through the appearance of the splendor of divine light in Christ, who deifies human beings through the grace of God.

However, Mary’s sorrow reminds us of the trials and tribulations that will be involved in becoming such a “partaker of divine nature” (2 Pet. 1:4). The wounded face of the Virgin, permeated by sorrow since she is united to the sufferings of her Son, “carries the believer to a world of different values . . . It records all human tensions, the gift and mystery of human existence, man called to life by the mystery of the cross honored by the grace of Christ’s resurrection.”[19] The face calls the viewer to intimately enter into the saving events of the life of Christ, who “being in the form of God . . . humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, even death on a cross” (Phil 2:6, 8). The image serves to as an invitation to overcome one’s sensual attachments, passions, and disordered desires, and to become obedient to the Word of God, Who is the content and source of the Gospels, and Who is also depicted in the icon. As Mary’s obedience to the Word of God bore salvific fruit in her womb, the viewer’s obedience to God’s Word as seen in the icon will be fruitful in her progress towards holiness.

This Black Madonna is thus the fitting image for both the Easter and Christmas seasons. We can easily accept the newborn babe in the manger cuddled and swaddled by the poor maiden from Nazareth, both of whom are under the watchful and silent gaze of the most chaste, and therefore most loving, Saint Joseph. Indeed, who would not be moved by this scene of tranquility and order? But are we willing to accept the consequences of what it means to declare that this newborn babe is King, the maiden is Queen, and the Carpenter is our protector and patron? Are we willing to recognize what it means that she leads us to her Son? Because, unlike Mary Magdalene in the Garden, who could not yet cling to her Lord (Jn. 20:17), this Mary brings us to her son, and asks us to worship him, to cling to his newborn flesh, to hold him in our hands and hearts; but then, she shows us that in holding this Christ, we are holding suffering flesh; to follow in the footsteps of this newborn babe is to follow the royal priestly path of suffering and death to self.

Through the transfigured and spiritualized Mother of God, who nevertheless bears the marks of a life of suffering and compunction, one is given a visual reminder of the meaning of the Incarnation, which accomplishes the restoration of humanity and the world. Mary is the New Eve, the mother of the New Adam who has re-created the human race. She bore him who “entering the actuality of the fallen world . . . broke the power of sin in our nature, and by His death, which reveals the supreme degree of his entrance into our fallen state, He triumphed over death and corruption.”[20] In her humility, Mary directs the viewer to this Second Person of the Holy Trinity, and she herself serves as a prototype of His saving work. By gazing at the fully human Mary, one is given an idea of what it means to cooperate with God, to die to self, to suffer with Christ, and to share in his glory. For this reason, the Second Vatican Council can say that Mary was by “the grace of God, as God's Mother, next to her Son, exalted above all angels and men” and is now “justly honored by a special cult in the Church . . . under whose protection the faithful took refuge in all their dangers and necessities” (Lumen Gentium, §66).

This is not exactly the kitschy plastic nativity figure of Mary we might find in our manger scenes.

[1] Franciszek Karpiński (1741-1825), “It seems that on Jasna Góra Stands that…,” cited in Franciszek Ziejka, “Writers of the time of the National partition on the Jasna Góra Pilgrimage Route,” Peregrinus Cracoviensis 3 (1996), 103.

[2] Kontakion, Sunday Orthodox Liturgy.

[3] John Paul II, “Speech to the Polish People” (October 23, 1978), in Insegnamenti di Giovanni Paulo II, I, 1978, 52.

[4] Stanisław Swidziński, “Die Schwarze Muttergottes von Tschenstochau,” in Internationale katolische Zeitschrift Communio-Verlag, 16:1 (January 1983), 69.

[5] Michel Quenot points out that the field of experimental psychology has studied the effect of colors on the emotional and biological states of a person. Thus, reds can raise one’s heartbeat and cause them to be excited. Hues of blue have a calming and soothing effect. See: Michel Quenot, The Icon: Window on the Kingdom (Crestwood, NY: SVS, 1991), 111. Studies have also shown that infant boys and girls react differently to various colors as a result of a differing kinds of cells in their retinas (boys have more magnocellular ganglion cells, while girls have more parvocellular ganglion cells). See Leonard Sax, Why Gender Matters (New York: Random House) 2006.

[6] See Robert Maniura, Pilgrimage to Images in the Fifteenth Century (Rochester, NY: The Boydell Press, 2004), 43.

[7] See Quenot, op. cit., 94.

[8] Ibid.

[9] A tradition which appears in many of the Church Fathers, originating with Saint Irenaeus, “As Eve was seduced into disobedience to God, so Mary was persuaded into obedience to God; thus the Virgin Mary became the advocate of the virgin Eve.” Adv. Haer. V.19.1.

[10] See Maniura, op. cit., 133 (italics mine).

[11] See Maniura, op. cit., 69.

[12] Ibid., 44.

[13] In the late medieval western Church, a tradition arose to contemplate the seven moments in Mary’s life where she would suffer in a particular way on account of her love of Christ. They are as follows: 1. The Prophecy of Simeon (Luke 2:34–35) 2. The escape and Flight into Egypt (Matthew 2:13) 3. The Loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple of Jerusalem (Luke 2:43–45) 4. The Meeting of Mary and Jesus on the Via Dolorosa 5. The Crucifixion of Jesus on Mount Calvary (John 19:25) 6. The Piercing of the Side of Jesus with a spear, and His Descent from the Cross (Matthew 27:57–59), and 7. The Burial of Jesus by Joseph of Arimathea (John 19:40–42).

[14] Constantine Kalokyris, The Essence of Orthodox Iconography (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross, 1971), 53.

[15] Quenot, op. cit., 97.

[16] Kalokyris, op. cit., 54.

[17] Stefan Rożej, “The Icon of Our Lady of Jasna Góra as a Biblical and Theological Synthesis,” in Peregrinus Cracoviensis 3 (1996), “Jasna Góra: The World Centre of Pilgrimage,” 54.

[18] Vladimir Lossky, In the Image and Likeness of God (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press: New York, 1974) 208.

[19] Rożej, op. cit., 54-55.

[20] Lossky, op. cit., 104.