Seán O’Hagan: For me, lighting a candle for someone may be more an act of hope than faith. And I tend to think of it as one of the few residual traces of my Catholic upbringing.

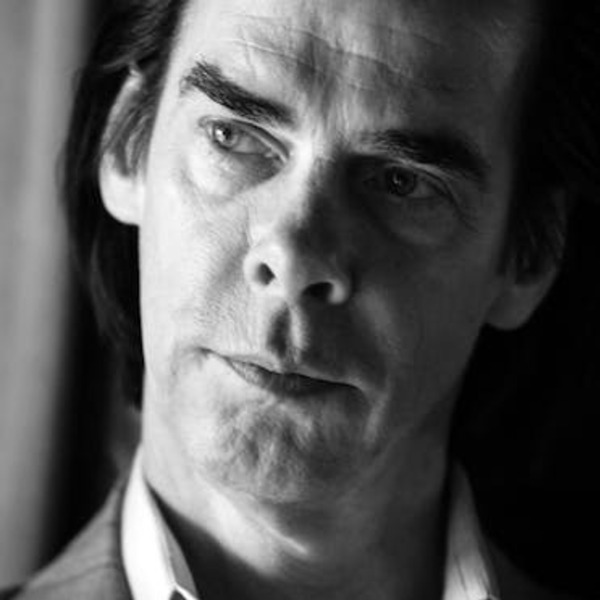

Nick Cave: Perhaps, but to go into a church and light a candle is quite a consequential thing to do, when you think about it. It is an act of yearning.

Seán O’Hagan: I guess so. And yet I struggle with what it means exactly. It may be that it just makes me feel better about myself.

Nick Cave: I think at its very least it is a private gesture that signals a willingness to hand a part of oneself over to the mysterious, in the same way that prayer is, or, indeed, the making of music. Prayer to me is about making a space within oneself where we listen to the deeper, more mysterious aspects of our nature. I’m not sure that is such a bad thing to do, right?

Seán O’Hagan: No, not bad, but not rational, either. Then again, it may be that the most meaningful things are the most difficult to explain.

Nick Cave: Yes, I think so. And I do think the rational aspect of our selves is a beautiful and necessary thing, of course, but often its inflexible nature can render these small gestures of hope merely fanciful. It closes down the deeply healing aspect of divine possibility.

Seán O’Hagan: I have to say that I am slightly in awe of other people’s devotion. When I go into an empty church, it always feels meaningful somehow—and vulnerable—to just linger there for a moment or so. Do you know Larkin’s poem, ‘Church Going,’ which touches on that very thing?

Nick Cave: Yes! ‘A serious house on serious earth it is.’ And yes, there’s something about being open and vulnerable that is conversely very powerful, maybe even transformative.

For me, vulnerability is essential to spiritual and creative growth, whereas being invulnerable means being shut down, rigid, small. My experience of creating music and writing songs is finding enormous strength through vulnerability. You’re being open to whatever happens, including failure and shame. There’s certainly a vulnerability to that, and an incredible freedom.

Seán O’Hagan: The two are connected, maybe—vulnerability and freedom.

Nick Cave: I think to be truly vulnerable is to exist adjacent to collapse or obliteration. In that place we can feel extraordinarily alive and receptive to all sorts of things, creatively and spiritually. It can be perversely a point of advantage, not disadvantage as one might think. It is a nuanced place that feels both dangerous and teeming with potential. It is the place where the big shifts can happen. The more time you spend there, the less worried you become of how you will be perceived or judged, and that is ultimately where the freedom is.

Seán O’Hagan: We’ve talked a lot about the shift in your songwriting style, but it’s surely a reflection of a much bigger and more profound shift of consciousness.

Nick Cave: Yes, one that came out of a whole lot of things, but I guess it is essentially rooted in catastrophe.

Seán O’Hagan: Was there ever a point after Arthur’s death when you thought you might not be able to continue as a songwriter?

Nick Cave: I don’t know if I thought about it in that way, but it just felt like everything had altered. When it happened, it just seemed like I had entered a place of acute disorder—a chaos that was also a kind of incapacitation. It’s not so much that I had to learn how to write a song again; it was more I had to learn how to pick up a pen. It was terrifying in a way. You’ve experienced sudden loss and grief, too, Seán, so you know what I’m talking about. You are tested to the extremes of your resilience, but it’s also almost impossible to describe the terrible intensity of that experience. Words just fall away.

Seán O’Hagan: Yes, and nothing prepares you for it. It’s tidal and it can be capsizing.

Nick Cave: That’s a good word for it—‘capsizing’. But I also think it is important to say that these feelings I am describing, this point of absolute annihilation, is not exceptional. In fact it is ordinary, in that it happens to all of us at some time or another. We are all, at some point in our lives, obliterated by loss. If you haven’t been by now, you will be in time—that’s for sure. And, of course, if you have been fortunate enough to have been truly loved, in this world, you will also cause extraordinary pain to others when you leave it. That’s the covenant of life and death, and the terrible beauty of grief.

Seán O’Hagan: What I remember most about the period after my younger brother, Kieran, died was a sense of total distractedness that came over me, an inability to concentrate that lasted for months. Did you experience that?

Nick Cave: Yes, distraction was a big part of it, too.

Seán O’Hagan: We talked earlier about the act of lighting a candle, and that for me was the only thing that could still my mind. It was as if peace had descended if only for a few moments.

Nick Cave: Stillness is what you crave in grief. When Arthur died, I was filled with an internal chaos, a roaring physical feeling in my very being as well as a terrible sense of dread and impending doom. I remember I could feel it literally rushing though my body and bursting out the ends of my fingers. When I was alone with my thoughts, there was an almost overwhelming physical feeling coursing through me. I have never felt anything like it. It was mental torment, of course, but also physical, deeply physical, a kind of annihilation of the self—an interior screaming.

Seán O’Hagan: Did you find a way to be still even for a few moments?

Nick Cave: I had been meditating for years, but after the accident, I really thought I could never meditate again, that to sit still and allow that feeling to take hold of me would be some form of torture, impossible to endure. And yet, at one point, I went up to Arthur’s room and sat there on his bed, surrounded by his things, and I closed my eyes and meditated. I forced myself to do it. And, for the briefest moment in that meditation, I had this awareness that things could somehow be all right. It was like a small pulse of momentary light and then all the torment came rushing back. It was a sign and a significant shift.

But when you mentioned that sense of constant distractedness, I was thinking about how, after Arthur died, there was a raging conversation going on in my head endlessly. It felt different to normal brain chatter. It was like a conversation with my own dying self—or with death itself.

And, in that period, the idea that we all die just became so fucking palpable that it infected everything. Everyone seemed to be at the point of dying.

Seán O’Hagan: You sensed that death was all around you, just biding its time?

Nick Cave: Exactly. And that feeling was very extreme for Susie. In fact, she kept thinking that everyone was going to die—and soon. It was not just that everyone eventually dies, but that everyone we knew was going to die, like, tomorrow. She had these absolute existential free-falls that were to do with everyone’s life being in terrible jeopardy. It was heart-breaking.

But, in a way, that sense of death being present, and all those wild, traumatised feelings that went with it, ultimately gave us this weird, urgent energy. Not at first, but in time. It was, I don’t know how to explain it, an energy that allowed us to do anything we wanted to do. Ultimately, it opened up all kinds of possibilities and a strange reckless power came out of it. It was as if the worst had happened and nothing could hurt us, and all our ordinary concerns were little more than indulgences. There was a freedom in that. Susie’s return to the world was the most moving thing I have ever witnessed.

Seán O’Hagan: In what way?

Nick Cave: Well, it was as if Susie had died before my eyes, but in time returned to the world.

You know, if there is one message I have, really, it concerns the question all grieving people ask: Does it ever get better? Over and over again, the inbox of The Red Hand Files is filled with letters from people wanting an answer to that appalling, solitary question. The answer is yes. We become different. We become better.

Seán O’Hagan: How long did it take before you got to that point?

Nick Cave: I don’t know. I’m sorry, but I can’t remember. I don’t remember much of that time at all. It was incremental, or it is incremental. I think it was because I started to write about it and to talk about it, to attempt to articulate what was going on. I made a concerted effort to discover a language around this indescribable but very ordinary state of being.

To be forced to grieve publicly, I had to find a means of articulating what had happened. Finding the language became, for me, the way out. There is a great deficit in the language around grief. It’s not something we are practised at as a society, because it is too hard to talk about and, more importantly, it’s too hard to listen to. So many grieving people just remain silent, trapped in their own secret thoughts, trapped in their own minds, with their only form of company being the dead themselves.

Seán O’Hagan: Yes, and they close down and become numbed with grief. In your case, I wondered at the time if you were even aware of the depth of people’s responses to Arthur’s death? The incredible wave of empathy directed towards you.

Nick Cave: Well, as far as the fans were concerned, yes. They saved my life. It was never in any way an imposition. It was truly amazing. And what you remember ultimately are the acts of kindness.

Seán O’Hagan: Yes, the small things that people say or do are often the things that stay with you.

Nick Cave: So true, the small but monumental gesture. There’s a vegetarian takeaway place in Brighton called Infinity, where I would eat sometimes. I went there the first time I’d gone out in public after Arthur had died. There was a woman who worked there and I was always friendly with her, just the normal pleasantries, but I liked her. I was standing in the queue and she asked me what I wanted and it felt a little strange, because there was no acknowledgement of anything. She treated me like anyone else, matter-of-factly, professionally. She gave me my food and I gave her the money and—ah, sorry, it’s quite hard to talk about this—as she gave me back my change, she squeezed my hand. Purposefully.

It was such a quiet act of kindness. The simplest and most articulate of gestures, but, at the same time, it meant more than all that anybody had tried to tell me—you know, because of the failure of language in the face of catastrophe. She wished the best for me, in that moment. There was something truly moving to me about that simple, wordless act of compassion.

Seán O’Hagan: Such a beautifully instinctive and understated gesture.

Nick Cave: Yes, exactly. I’ll never forget that. In difficult times I often go back to that feeling she gave me. Human beings are remarkable, really. Such nuanced, subtle creatures.

Excerpted from Faith, Hope and Carnage by Nick Cave and Seán O'Hagan. First published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, now out in paperback with Picador. Copyright © 2022 by Lightning Ltd (on behalf of Nick Cave) and Seán O’Hagan. All rights reserved.