Some parts of life are much better sped up. For example, if you must drive from one city to another, how much nicer it would be to teleport—or, less fancifully, if better roads allowed a faster trip. If you are enduring a splitting headache, you want it to end immediately. Snapping a finger to summon a cleaning robot has been a fantasy since The Jetsons. Even better if a souped-up Roomba could scrub toilets, wash dishes, and dust.

But there is much in life we do not want to speed up. A good meal deserves to be savored. Nor would many amateur chefs be pleased to hear that a cooking robot could best their earnest efforts with a 10-minute flurry of chopping, sautéing, and convection heating. Maybe three years of college would be better than four, but two or one? An afternoon-long brain-download of the Great Courses Plus courtesy of Elon Musk’s Neuralink? I would not want it, just as I would be unhappy if an exoskeleton powered me through my walks in parks or museums in 15 rather than 45 minutes. There is something more to a meal, cooking, education, strolls, than their end result.

We might style this divide between the “better-faster” and the “better-savored” as a tension between the instrumentally and intrinsically valuable. A flight to Albuquerque is merely a means of getting me to New Mexico; appreciating its vistas is an end in itself. In Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity, German social theorist Hartmut Rosa explored the many ways that the increasing speed of so much of life—the news cycle, financial markets, dating, etc.—are both alienating and an increasingly inexorable trend. Rosa’s recently translated Resonance explores why some speed-ups are happily-greeted, while others grate.

For example, to return to our meal example: Rosa phenomenologizes eating, carefully exploring how the meal grounds us in relationship to nature (the ultimate source of food), and companions (who may join us in enjoying together). We are literally incorporating the world into ourselves: as Rosa observes, “there is no more elementary, no more porous way of relating to the world” than chewing and swallowing it. A resonant relationship to food starts with an appreciation of plants and animals. It may grow into a noble commitment to a more just political economy, reduction in animal cruelty, and advances in sustainability. In all these ways eating is not just a means to an end (fuel-seeking), but an occasion for reflection and connection.

Silicon Valley entrepreneurs may push “Soylent Green” in hyper-efficient feedbags, to be consumed as fast as possible (perhaps to give the user more time on the newsfeeds of Facebook and Twitter). Time-pressed people may buy into this vision of instant meals, particularly if their usual fare is not all that savory. And who among us has not wolfed down a meal absent-mindedly? Nevertheless, we must limit the pressures that may lead us to do so. Meal rituals persist in cultures around the world, bounding the demands of capital for more of our time. As the beautifully realized film Every Day a Good Day quietly demonstrates, a tea ceremony can be centering practice of solace and wonder, connection with others and concentration on the task at hand.

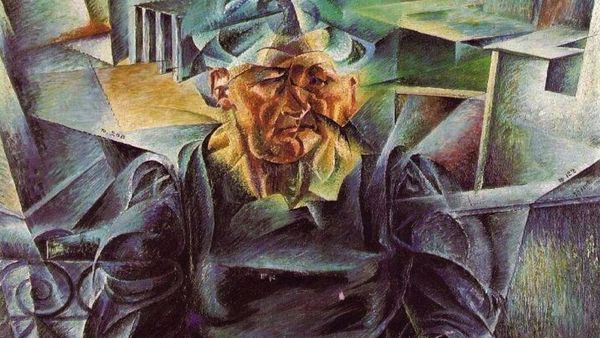

An ethical stance of attunement to resonance also commends forms of receptivity and sensitivity to beauty as well. Rosa discusses in great detail how nature, art, and history serve as sources of resonance. Nature is the key point of entry, given how viscerally we can all experience it each day. Quasi-religious forms of environmentalism should come as no surprise, as Rosa identifies nature as “a—or perhaps even the—central sphere of resonance in modernity.” “Faced with the expanse of the sea or a landscape, or under the warmth and light of the sun,” Rosa writes, “our breathing, posture, skin resistance, and the alignment or orientation of our sensory apparatus all literally change; our psychophysical relationship to the world changes.” He chronicles the ways large and small, immediate and ramified, in which nearly everyone seeks some direct experience of nature. Devotion to pets can be read as manifesting this primordial will to relate to the world, rather than as its self-serving domestication.

As those rival interpretations suggest, Rosa’s work is not a scientific treatise, declaiming the last word on what meaning and resonance entail. Rather, as this enormously ambitious work seamlessly turns from phenomenology to social theory to political economy, Rosa crafts “resonance” as a master metaphor for finding meaning in life, and avoiding alienation. Indeed, the work’s discussion of alienation is a brilliant summation of that critical term’s evolution, and might more profitably appear at the beginning of the book. We can understand the positive program of Resonance best as a response to alienation, which Rosa earlier diagnosed as one consequence of social acceleration.

The vagueness and breadth of terms like alienation and resonance might seem like a weakness—how is one to build an analysis on the shifting sands of essentially contested concepts? Instead, their polysemy serves as a great strength of the work, making it capacious enough to accommodate debates among positions based on myriad worldviews. Imagine, for instance, a person who eschews all contact with the natural world, preferring instead to interact with its digital representation in a hyper-realistic video game. Does such a person experience resonance? Or, might a Rosa-inspired theorist deem him, instead, hopelessly alienated?

Richard Powers’s novel The Overstory movingly wrestles with this question in its depiction of a coding wunderkind (Neelay Mehta) who, paralyzed in youth, develops a video game that brings virtual forests and savannahs to anyone with a sufficiently fast internet connection. He is described in the book as “the boy who’ll help change humans into other creatures.” With a restraint that is both frustrating and admirable, Powers does not pass judgment on whether this change is positive. Nor does Rosa’s work decide the issue. However, it does give us a powerful vocabulary to adjudicate whether (and which) screen time is a boon or bane, far richer than the one-dimensional outcome variables of methodologically individualistic psychology studies of children online.

In Rosa’s worldview, a feeling of alienation is a clue that our time may be misspent, or, worse, that we are trapped in a dehumanizing society. Walker Percy’s “man on the train” comes to mind. Or, as Adorno once put it in Minima Moralia, “the wrong life cannot be lived rightly” (or, more literally, “there is no correct life in the false one”).

But in each of the situations raised above, another type of interpretation—a biological explanation—can be proposed. The pleasure and meaning of a good meal can be chalked up to various hormones and neurotransmitters, eventually to be replaced by chemicals or Neuralink’s microtargeted electrical currents to the brain. An evolutionary biologist may reframe musical appreciation as a tool for uniting tribes, and thus an advantage in Darwinian competition for resources. Our sense of our personal and communal history may be downgraded to the status of one story among others, clung to merely in order to contrive a “useable past.” All these deflationary frames unweave the rainbow of resonance. They menace Rosa’s project, claiming to offer more fundamental, naturalistic explanations for the phenomena he puts at the center of human experience.

To his great credit, Jason Blakely has been challenging these naturalistic approaches for years. In a long series of rigorous analyses, Blakely has promoted “anti-naturalism” as a unifying theory of a renewed social science: one that respects, but does not ape, the methods of physics, chemistry, and biology. In We Built Reality, Blakely distills and applies his prior, more theoretical work into a powerful indictment of those social scientists who claim to be more “objective” and “reality-based” than work like Rosa’s value-laden account of resonance. For Blakely, all social science is value-laden. The naturalists just happen to be particularly skilled at applying a patina of “science” to their own highly contestable theories of human nature, motivation, and purpose.

Psychology, economics, and their integration in behavioral economics, are particularly fruitful targets for Blakely. He describes an unholy alliance between big pharmaceutical firms and academics who seized on depression diagnoses as a chance to offer,

A method that used the language and authority of science to offer a discipline for the transformation of self. This self viewed the sources of the malaise as entirely materialistic, barring any serious standing for spiritual or political grievances.

As Johann Hari’s Lost Connections has passionately argued, all too much mental illness is treated solely as a problem of chemical imbalance. There are many ways to interpret maladies, and we lose a great deal when we limit the discussion to psychopharmacology. There is a critical asymmetry, too: the expert on brain science all too often monopolizes authority that might once have been shared with psychiatrists, social workers, neighborhood organizers, pastoral counselors, writers, and, of course, the patient.

Blakely indicts condescension in numerous works of pop social science, including Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s celebrated “libertarian paternalism” (a suitably Orwellian self-designation). While Thaler and Sunstein cast themselves as humble helpers of an akratic populace, Blakely argues that, in their book Nudge, “there is a sense that the majority of people are only marginally capable of self-rule because they consistently embody the automatic, biased, irrational aspects of the brain.” So “choice architects” must direct them by, for example, defaulting them into 401(k) savings plans, or putting candy on lower shelves so it is harder to reach.

Of course, robust solutions to problems of retirement savings or obesity are far more ambitious than Thaler and Sunstein’s agenda. Thus, William H. Simon once observed that the nudge mentality:

Implies an oddly constrained conception of the means and ends of government. It sometimes calls to mind a doctor putting on a cheerful face to say that, while there is little he can do to arrest the disease, he will try to make the patient as comfortable as possible.

This minimalism is unsurprising. Deep democracy is hard to imagine among subjects modeled to be as thoughtless, adrift, and manipulable as libertarian paternalist’s nudge-ees.

Blakely’s lively and impassioned prose is a revelation, popularizing critical social science. He compiles the subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which we are persuaded to see ourselves, and society as a whole, as mechanical objects in need of expert guidance and manipulation, rather than as reflective agents narrating a past and imagining a better future.

The machine metaphor sometimes becomes literal: witness, for example, the advice in the popular book Algorithms to Live By on how long to look for a spouse. Computer scientists frame some problems of finding or harvesting as “explore/exploit:” how long to look for a set of resources, versus how long to exploit the resources where one already is. Applying similar reasoning to the problem of dating, the authors of Algorithms to Live By suggest that those dating should shift from looking to leaping at age 26.1, assuming one gives oneself ages 18 to 40 to find a mate. This is based on a “37 percent rule,” which, as Blakely explains, “holds that because individuals have a finite amount of time and resources to attract mates, they ought to optimize their decision by neither concluding their search too early (before seeing enough ‘data’) nor carrying on too long (after losing the best opportunity likely to come along).” Apparently once one meets someone “better” than the first 37% of options one has already tried, that person is very likely to also be better than anyone else coming down the pike (or the margin by which they are worse is less valuable than the time spent looking further).

Blakely finds this mathematical modeling objectionable for several reasons. The “algorithmic approach assumes that erotic love deals not with the event of a single, nontransferable person but with an abstract set of qualities or resources that recur across individuals and can be optimized.” This is ultimately a dehumanizing way of “dividualizing” people (as Deleuze put it), decomposing them into qualities according to what David Beer aptly calls a “data gaze.” It risks misconceiving marriage or life partnership from a solipsistic, “me-first” perspective. “For better or worse, in sickness and in health” is rarely a rational commitment to make. It is, instead, a pledge of self-giving and devotion, the start of a story about who one is and what commitments are of ultimate importance.

In both Rosa’s and Blakely’s books, we are given a rich alternative to the dominant utilitarianism, economism, and cost-benefit analysis that have become cornerstones of contemporary decision-making, and even self-understanding. They are ultimately inviting us to narrative: to tell richer, deeper, more honest stories about our personal and collective past and destiny (rather than trying to determine which course of action will maximize personal wealth or optimize social order). The test of social science is neither precision nor control, especially in an era of ever more shockingly unexpected developments in climate, technology, and social order. Rather, as Bevir and Blakely argue in their joint work Interpretive Social Science, “the goal of social science is not a final set of explanatory laws, but always better . . . stories and descriptive insights.”

While Resonance is a tightly structured work of social theory, it also succeeds narratively, presenting us with a rich set of case studies of lives lived well or badly. The book offers us a “concept of a difference between successful and unsuccessful relationships to the world defined neither by the relative abundance of resources and opportunities nor by one’s share of the world, but by the degree to which one is connected with and open to other people (and things).” Sadly though, work like Rosa’s is far from the center of contemporary sociological inquiry. Hard-nosed empiricists would happily relegate it to philosophy, aesthetics, or even self-help. But as Blakely shows, too many of those empiricists stealthily encode their own philosophic and aesthetic preferences into their projects. By failing to acknowledge their own value commitments, they have deflected the ultimate questions, of meaning and purpose, that Rosa so wisely foregrounds.

Goethe once observed that “the chief goal of biography appears to be this: to present the subject in his temporal circumstances, to show how these both hinder and help him, how he uses them to construct his view of persons and the world.” In the end, we must all narrate some autobiography of our time on earth—how we spend our limited days together. Blakely warns us away from the reductionist narratives that would make such self-narration a matter of brain chemistry, the mental states supervening on mere, materialist, matter in motion. In the process, he sketches the richer concepts of self and society that Rosa systematically presents as sources of resonance. Both works should be at the foundation of a new, more generous, view of our nature, destiny, and purpose.