God has a very fresh and living memory of the smallest and most forgotten.

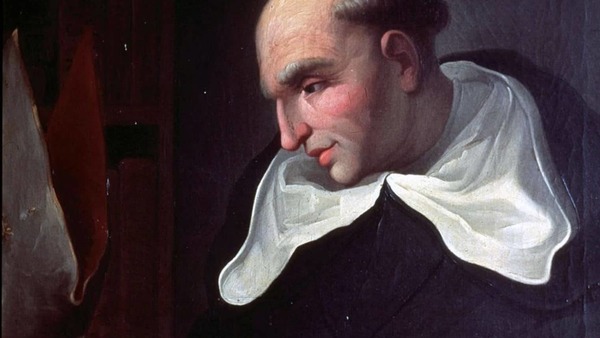

—Bartolomé de las Casas, OP

People rightly ascribe to Friedrich Nietzsche the role of the core thinker behind the idea of genealogical thinking. Yet, part of my editorial work is to think through different ways of doing genealogical work while tracing my own typologies of genealogical thinking. This includes looking at alternatives to Nietzsche’s approach, which has tended to dominate the academy. To see an alternative, I want to look at two other genealogists, Augustine and Bartolomé de las Casas, OP. In particular, I want to highlight how Christian genealogies can work to critique imperial and colonial projects.

To understand Fray Bartolomé and Augustine, we need to understand why these two theologians wrote histories. Their approach to writing history is a genealogy of the morals of imperial projects. This genealogy expresses the core theological realities of the civitas terrena. Each colonial project re-enacts the genetic flaw of the earthly city, the theft of one’s brother. Their projects operate around a genealogy of original theft that marks a community and expresses itself throughout the life of that community. Their historical writing critiques imperial histories by telling the true stories of colonialism. Their writing uncovers the impulse to theft within the fratricidal impulse that underlies imperial projects and all forms of sin.

These original thefts form pseudo-communities based around a lie. This lie is the denial of the fraternal nature of our relationship with all people. The deception lives on in the lies that cover over the original theft thus constantly repeating this theft. The work of these two theologians is in service of memory and against pernicious forms of misremembering. For a Christian genealogist, a genealogy of an original theft does not collapse into a story of evil alone. Like Augustine, we apply a hermeneutic of suspicion but in service of caritas which is the forgotten but deeper reality of creation. Christian genealogical work operates on the principle that God’s love is deeper than our will to power.

Christian genealogists write about history within the context of God’s Memory, which motivates our work of human memory. Augustine’s and Fray Bartolomé’s genealogies speak of deeper stories, particularly the truth of our kinship through God’s creative act and Christ's redemptive act. Their approach is then to critique the origins and ethos of imperial and colonial projects within the context of an expression of God’s memory for the smallest and most forgotten. There are some stories that run deeper than the will to power and express our capacity for God and our fundamental fraternity grounded in the mystery of Divine Memory.

What Is Genealogical Thinking?

What exactly is genealogical thinking? Before we answer this question we should note that the two Christian thinkers discussed here predate the Nietzschean origins of this way of thinking by over a millennium. Yet, they are doing genealogy avant la lettre. And so, genealogy is the study of origins, development, and family relations of ideas and forms of life. This can be understood in a few ways.

The first is the study of the conditions for the possibility of forms of life and of the development of certain ideas. The core questions here are: what makes possible certain ways of living and certain ways of thinking? How and when did these possibilities arise? (see: Nietzsche's Genealogy of Morals or David Lantigua's essay on human rights for two very different versions of it).

The second aspect of genealogical thinking is a type of critical or revisionist history that tries to show how the stories we tell about history mislead us about the past. This is done in large part by showing how they were constructed as a form of misremembering. By obscuring the past, these stories make impossible present understanding and future change. The goal here is to provide either a more truthful history or a more effective history (for instance, to advance some account of justice). Of course, one might be trying to do both.

Lastly, Genealogy is about possibility and contingency. It insists on the importance of temporality without determination. Historical understanding is so important because history did not have to be that way. By showing the contingency of the past, the unexpected origins of the present, and developments that did not happen but could have happened, we make possible different futures. As I have argued elsewhere, this does not necessitate a rejection of God, but a navigation of the traces of God in history to see the intersection of the timeless with time.

Dwellings of Thieves

Fray Bartolomé wrote history as an act of prophetic witness. Stephen Merrim claims he wrote “more as an outrage moralist than as a historian.” He sought to disclose the origins of colonialism as it expresses itself over time in the colonial project of Spain. In this, he does not write as a modern historian nor as a medieval chronicler. He writes in a genealogical mode within the tradition of Augustine’s City of God.

Both Fray Bartolomé and Augustine write their histories to critique an ethic of theft in order to extoll an ethic of love. Both used historical writing as prophetic denunciations and projects of immanent critique within their respective empires. In their critical mode, they composed texts as counternarratives to imperialism which reject modes of human life based in theft from the other. Augustine’s City of God re-narrates Roman history by interpreting Roman power as theft on a grand scale. This stems from his genealogy of the origins of Rome which lie in the murder of a brother, the theft of his goods, and the denial of fraternal responsibility. Writing in a different context, Bartolomé de las Casas sought to use history to critique a colonial enterprise.

Both write history to demythologize imperial propaganda. In Augustine’s case, the pagan history of a virtuous Rome. In Las Casas’s case demythologizing Spanish propaganda by showing Spain’s failure to live up to its Christian commission of evangelization. Rather than bringing good news to others, the Spanish enacted, en masse, the theft of the other.

This took the form of the theft of a continent, the enslavement of the Indigenous, and the denial of fraternal responsibility. Augustine and Fray Bartolomé use history as a critique of false models of human relationality which see theft as the fundamental form of interrelation. Their projects were also summonses to seek more positive forms of community life. This is particularly the case with Fray Bartolomé’s mode of writing. Through history, he affirms the humanity of the Indigenous people, their relation to the Spanish as members of the human family, and their capacity for God.

These two thinkers used genealogies to provide counternarratives to Roman and Spanish histories. Genealogical work often seeks to unmask a story of origin that the dominant account tries to constantly cover over by glorifying it. As Santa Arias puts it, “In the sixteenth century, historiography functioned as an ideological apparatus that either legitimated and perpetuated the politics of the state or served as an instrument of political intervention and reform.” Fray Bartolomé sought to resist this with texts like In Defense of the Indians and A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Likewise, Augustine’s City of God, as a historical text, is not meant to change the reader's understanding of what happened in Roman history but rather of the moral character of the things that happened.

While Augustine writes in a tradition of Rome’s moralizing historians, he attempts to deconstruct this very tradition. He does not appeal to some moment in history when Rome was virtuous in order to reform or buttress the current order (think: Varro) nor does he propose a kind of gradual improvement of things into a Christian Empire (think: Eusebius). Instead, he seeks to deconstruct the idea of any virtuous imperial project, whether it is Christian or not. To be imperial is already not to be virtuous (just as Fray Bartolomé will show that there is no virtuous colonial enterprise). Augustine’s goal is to show that empire from its origin is vicious because it is always based on theft from our brothers and sisters and so theft from God.

To show the corrupting influence of this original theft, Augustine wrote in the City of God about all empires, a passage which was later central to Fray Bartolomé’s own project:

Justice removed . . . what are kingdoms but great bands of robbers? What are bands of robbers themselves but little kingdoms? The band itself is made up of men; it is governed by the authority of a ruler; it is bound together by a pact of association; and the loot is divided according to an agreed law. If, by the constant addition of desperate men, this scourge grows to such a size that it acquires territory, establishes the seat of government, occupies cities, and subjugates peoples, it assumes the name of kingdom more openly.

For Augustine, justice has been removed from all civitates because none rightly give what is owed (love) to God or to neighbor. Augustine magnifies this by arguing that empires do not merely fail to give, they actively steal. They take glory from God and life and livelihood from others. They justify themselves by their false histories of glory, but such histories are the lies of successful thieves. Augustine exposes the immorality of each age of Rome to show that to be imperial is to be a successful band of robbers.

The genealogical move is key because it indicates that empires are bands of thieves from their origin. The description of Rome’s origin, in The City of God, is short and bitter: “This is how Rome was founded . . . Remus was slain by his brother Romulus.” This murder was based on the desire to steal from the brother. “Both sought the glory of establishing the Roman commonwealth, but could not both have the glory . . . for the sway of anyone wishing to glory in his own lordship is clearly less extensive if his power is diminished by the presence of a living colleague.” What should have been shared was stolen. The killing of a brother was necessary to accomplish the theft. “His colleague was removed; and what would have been kept smaller and better by innocence was increased through crime into something larger and worse.” Rome, under its founder Romulus, would grow from a solitary thief to a republic of thieves to an empire of thieves.

What flows from this founding by theft and fratricide is an empire marked by theft (usually from other peoples) and by fratricide (especially in civil war). Rome is a microcosm of the Earthly City itself for “the first founder of the earthly city, then, was a fratricide; for, overcome by envy, he slew his brother, who was citizen of the Eternal City and a pilgrim on this earth.” Augustine leaves no room for virtuous empires because they all depend on their archetype: brother killing brother, out of envy, in order to take from the other. All the historical work of figures like Varro and Sallust (or American apologists) papers over these realities. Genealogical work shows the violence and robbery at the heart of the city. Amidst these bands of thieves, Augustine leaves room for only one virtuous city: the pilgrim city, traveling through or between these empires of thieves.

This idea that empires are large collectives of thieves is key to the Augustinianism of Fray Bartolomé. As his critique of the Spanish imperial project deepened, he increasingly saw the power of Augustine’s words about thieves. He writes in his History of the Indies: “what do we see in great kingdoms without justice, but great lactrocinios, which according to St. Augustine, is to say, the dwellings of thieves.’” Spain, in its imperial project has revealed itself to be a band of thieves. In his Defense of the Indians, Fray Bartolomé harkens back to Rome: “The Roman empire did not arise through justice but was acquired by tyranny and violence.” So too is the Spanish empire being built by tyranny and violence. When he notes that some thought Rome had “some moral virtues” he too identifies this as deception for “according to Augustine these were not true virtues.” The actions of Spain in the New World were actions that disclosed the false virtue of Spanish colonialism.

Fray Bartolomé felt compelled to write the histories of conquest. His History of the Indies needed to be written due to “the great and desperate need all Spain has of truth and enlightenment on all matters relating to this Indian world.” This enlightening is an uncovering of the truth of the evils of the Spanish colonial project in order to bring about an end to Spanish colonization. The Defense of the Indians makes clear that the history of colonization is a history of “These thieves, these enemies of the human race” not of a glorious discovery followed by the preaching of the gospel.

The truth lurking below Spain’s celebration of itself was that it grew worse as it gorged itself on the gold of the New World. To write these histories is to advocate for a different relation between brothers, one in which we share the Gospel without forcing the Gospel, in which we respect their lands without appropriating them, in which we honor their cultures without dehumanization.

Spain’s empire was corrupted by the desire to seize what belongs to another instead of sharing what fundamentally belongs to all. In his Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, Fray Bartolomé writes: “The reason Christians have murdered on such a vast scale and killed anyone and everyone in their way is purely and simply greed. They have set out to line their pockets with gold and to amass private fortunes.” Fray Bartolomé condemned the Spanish desire for gold as idolatry: “wealth they hold for their god.” These two desires—greed and ambition—are the driving force behind a mass theft in the Americas. They reveal the idolatry of colonialism.

Their presence at the origin of the Spanish colonial project has corrupted what should have been a righteous endeavor. There had been an original reason for the Spanish arrival in the Americas. Fray Bartolomé’s History of the Indies is meant to remind people “of the goal for which divine Providence meant the discovery of those people and those lands, which is none other . . . than the conversion and salvation of those souls, to which end all temporal concerns must necessarily be subordinated.” The whole meaning of the “discovery” of these peoples was to share with them not take from them. It was the goodness of the Gospel that they were meant to share; not gold that they were meant to take.

A genealogy of theft discloses the more fundamental reality of what God intended for us: not that we steal from our brothers and sisters but that we share with them. Sin, particularly expressed through colonialism and racism, rejects God’s intention. Fray Bartolomé held Augustine’s basic conviction that “A man’s possession of goodness is in no way lessened by the advent or continued presence of a sharer in it. On the contrary, goodness is a possession which is enjoyed more fully in proportion to the concord that exists between partners united in charity.” He held to this because he never lost his zeal of missionary work even as he saw it so frequently betrayed.

His denial of absolution to the conquistadors until they freed the Indigenous is grounded in the Augustinian insight that “he who refuses to enjoy this possession in partnership will not enjoy it at all.” Worse is the person who refuses to share and instead seizes. For Fray Bartolomé and Augustine such a one will never enjoy the good and so can never enjoy the brotherhood of all with all.

A Fraternity Denied

Fray Bartolomé grounds his critique of the Spanish empire in the Augustinian terms of a band of robbers, but he also relies on the language of fratricide. This is a central task of his writing on behalf of the Indigenous, particularly in his The History of the Indies. He is trying to get the Spanish to realize that the Indigenous are our brothers and sisters. Like Augustine, he sees theft and fratricide as bound up together. Whenever we steal, we steal the common inheritance from our brothers. Humanity is not an aggregate of the unrelated, we are all kin.

Christian genealogy acts as critique because it points out the fratricidal drive in the human condition while it traces the truer family tie of humanity. Augustine highlights the fratricide that marks humanity (through Cain and Abel) and the imperial project (through Romulus and Remus) because he thinks it is emblematic of our violation of the fraternity of humanity. We see in The City of God that God “created only one single man . . . so that by this means, the unity of society and the bond of concord might be commended to him more forcefully, mankind being bound together not only by similarity of nature, but by the affection of kinship.” In the creation of many from one, Augustine maintains that the essence of humanity lies in our sociality as kin. Cain and Abel, Romulus and Remus show in larger form the nature of all our sins against each other. Each sin is an attempt to take what is common and make it private. Sin is always theft from our brothers and sisters.

Fray Bartolomé’s work in insisting on the fraternity of all builds on Augustine’s. The theft of the Indians is always a violation of our brethren. As Santa Arias writes, “Las Casas took on the role of historian because it legitimated his position as a spokesman for a repressed community.” He needed to show that he knew the Indigenous in order to defend the Indigenous. Consistently, he praises their cultures and their way of life in order to insist that their lives mattered. This relates to his philosophy of evangelization, which depends on understanding those you evangelize.

He insisted his confreres learn the language and customs of the Indigenous. In his theology of evangelizing, The Only Way, he insists on this as an expression of the way of “teaching a living faith to everyone everywhere, always.” This one way is “the way that wins the mind with reasons, that wins the will with gentleness, with invitation.” There is only this one way because that is how we are meant to talk to our brothers and sisters.

It is this that motivates Fray Bartolomé’s attempts to prove the shared humanity of the Indigenous. He writes both his Defense of the Indians and his History of the Indies to insist on the full humanity of the Indigenous. This is why he expends so much effort extolling their natural virtues, the value of their culture, and even the richness of their religious practices. He does so to maintain their rights as persons but, more importantly, to maintain that they are our fraternity. This cannot be done by generic claims to human nature, though Fray Bartolomé affirms this. Rather, what is needed is to affirm that these oppressed people are our brothers and sisters. To insist not that all lives matter, but that black and brown lives matter.

More than a claim about human nature, this is a claim about human family. To be a human is to live a fraternal reality. While Augustine looks to creation for our sociality, Fray Bartolomé tends to see this fraternity as based in Christ. In The Defense of the Indians, he writes “The Indians are our brothers, and Christ has given his life for them. Why, then, do we persecute them with such inhuman savagery?” Again and again Las Casas will insist on this. “They are our brothers, redeemed by Christ’s most precious blood.” The murder of the Indigenous is not the killing of unrelated humans, it is the killing of our brothers and sisters in Christ. For Augustine and Fray Bartolomé, to steal from the other, to kill them, is always to steal from and kill our kin. This is the genetic flaw of any imperial project because any imperial project requires the seizure of what belongs to our brother. It ultimately depends on the seizure and murder of our brothers.

Three Deeper Stories

Both Augustine and Fray Bartolomé do a genealogy of imperial and colonial projects grounded in a genealogy of the earthly city itself. Both use these genealogies to point to deeper stories. Neither is a Nietzschean, in that they think that the will to power is a corruption of a deeper story of the will to love. This deeper story is never fully effaced, is redeemed by Christ’s intervention in the histories of thieves, and will be fulfilled when all bands of thieves are cast down by the Kingdom of God. When we unmask empire, through a genealogy of original theft, we disclose a different possibility for human sociality.

The deeper story for Augustine is that prior to Cain and Abel there is a sociality of kinship that is ineradicable. The deeper story of Fray Bartolomé is that—despite the betrayal of Christianity by colonizers—Christ’s blood has redeemed the Indigenous and so made them our brothers. In the History of the Indies (written in Spain), he writes, “I leave, in the Indies, Jesus Christ, our God, scourged and afflicted and buffeted and crucified not once but millions of times”

In Christ, we all share the same blood. In a unique way, Christ lives in the oppressed, is the oppressed. My sin is thus always against my kin, always against Christ. The blood of the oppressed is the blood of my brother. The Lascasian hope is that our kinship may free us from our sinful social structures so that we will stop seeing our brothers’ blood in the streets.

Another deeper story is that, for Fray Bartolomé and Augustine, all peoples share a familial origin and a familial goal. This shared origin and goal is due to our orientation towards God. Humans are humans because of our capax dei. Augustinians should never forget that it is not only white people whose hearts are restless for God. This is why Fray Bartolomé insists that the Indigenous have the same “capacity for doctrine or for performing the acts of faith or love” as the Europeans. Both thinkers write histories that depend not only on a sense of a deeper past but also on a sense of a deeper future. We were made for God. The power of empires is enabled by the lie that their perverse order is the only order. The Christian genealogists insists on an original and ultimate order that will “cast down the mighty from their thrones” (Luke 1:52). This eschatological insistence enables thinking of a different ethos now whether in Fray Bartolomé’s prophesying against Spain or Augustine's work for communities vivified by the works of mercy.

The third story regards memory. As Cyril O’Regan has argued, the task of Christians is to resist both forgetting and, more perniciously, misremembering. Christians then must remember rightly. O’Regan writes in The Anatomy of Misremembering that “access to Christ is given in the field of the plural memories of the glory of God in Christ, since their center is Christ and the triune God their circumference.” Christian life is a life of memory. Memory regards the history of the Body of Christ over time and also the practice of presence before God. This means bringing Christian memory to bear against the violation of the poor, the oppressed, and the colonized.

Through memory, Christians must resist the demonic ordering of this world. This is a shared vision of both Augustine and Fray Bartolomé, two theologians of memory. In The Life of the Mind, Hannah Arendt writes that of:

Augustine’s three mental faculties—Memory, Intellect, and Will—one has been lost, namely, Memory . . . And this loss turned out to be final; nowhere in our philosophical tradition does Memory again attain the same ranks as Intellect and Will. Quite apart from the consequences of this loss for all strictly political philosophy . . . what went out with memory—sedes animi est in memoria—was a sense of the thoroughly temporal character of human nature and human existence.

One exception to Arendt’s genealogy of the forgetting of memory is Fray Bartolomé. Like Augustine, he wrote history because of his commitment to the importance of memory. Memory—as our capacity to be temporally and so historically—holds in play past, present, and future. Its stretching towards the eternal while never ceasing to be temporal means that we can know the deeper story of things. Memory allows us to witness against sin and to confess our sin. This is why Fray Bartolomé would not let the Spanish forget what they were doing to the Indigenous. His words demand that we not forget what we have done, and are doing, in this hemisphere.

Deeper even than memory in its human form is the memory of God. For Augustine, in On the Trinity, we image God through memory, understanding, and will. Memoria is our soul as imaging the Father. We remember because of God’s memory and thus each person must direct their whole selves to “remember, to see, and to love this Highest Trinity, in order that he may recall it, contemplate it, and find his delight in it.” But to do this, we must love our brother for “he who does not love his brother is not in love; and he who is not in love is not in God, because God is love.” Implicit in Augustine’s reasoning then is the need to remember our brother, to remember that each and all are our brothers. We cannot love the brothers we have forgotten. This is why it is so important to say their names.

Fray Bartolomé makes this implicit connection clearer. If our memory is an image of God the Father, then we need to conform our memory to God’s memory. This connection with divine memory is the ground for the preferential option for the poor. Fray Bartolomé writes that “God has a very fresh and living memory of the smallest and most forgotten.” If God keeps in mind the smallest and most forgotten, then in order to rightly image God, we must keep in mind the smallest and most forgotten. As Gustavo Gutierrez writes, in Las Casas: In Search of the Poor of Jesus Christ, that:

Bartolomé proposed to make God’s memory the guideline of his life and reflection. His outlook has deep biblical roots. The “memory of God” is an expression of the divine fidelity and accordingly places a demand on every Christian as well . . . for to neglect to love a person in need is to forget that one is Christian.

In this, Fray Bartolomé maintains Augustine’s sense of memory in its rightful place while seeing in it the capacity to write history on the side of the oppressed. God the Father always remembers the oppressed, he sent his Son to be with the oppressed, they send the Spirit to be the advocate for the oppressed. We must likewise remember, serve, and love. Part of the Christian genealogical task then is to do the prophetic work of remembering rightly, which is to remember in conformity with the Will of God not with the will to power. Christian memory must be in the service of God’s memory which keeps in mind the way we oppress the poor and people of color in this nation. That God remembers should be a source of hope and trepidation.