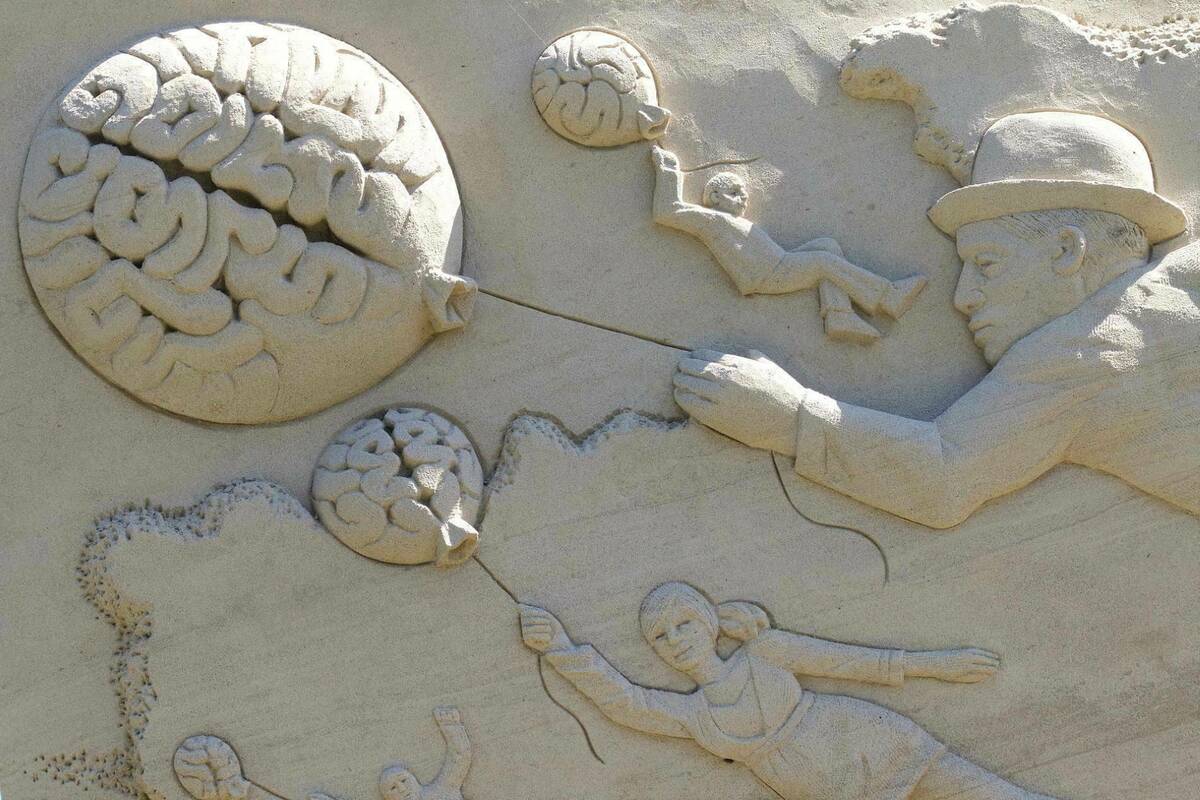

Since the end of the nineteenth century[1], the brain has held a regnant place in Western notions of the human person. With the dawn of modern experimental methods of stimulating and imaging the nervous system, scientists obtained incontrovertible evidence that the brain is a necessary physical substrate of human thought and behavior. This conclusion has undoubtedly yielded good fruit both in our medical practice and our self-awareness as a species. But it has also fueled a peculiar form of reductionism: the view that the neural is the primary explanatory level of reality.

This neurocentric ideology is not new. Back in 1680, one of the founders of neuroanatomy, Nicholas Steno, bemoaned the materialists who “do not want to admit . . . ignorance of the manner of how mind and body unite” but construe the mind as simply a different attribute of the brain.[2] Steno would shudder with horror at many contemporary interpretations of neuroscience. Vocal leaders of various institutions in our society—from education to business leadership to the mental health industry—now see the brain as the central and sufficient feature of human life. This is a gaze that impoverishes the anthropological realities they serve.

The commitments and costs of the neurocentric vision are evident in a lifestyle fad that recently swept through Silicon Valley: the practice of “dopamine fasting.” To undertake such a fast, one abstains from all pleasurable stimuli—including food, music, technology, and sexual activity—for a day or longer. Its name reflects the underlying supposition that abstinence from hedonic experiences re-sensitizes us to the action of this neurotransmitter, thereby heightening productivity and contentment after the fast ends—a bit like a coffee break restores our sensitivity to caffeine. In other words, dopamine fasting aims at a temporary therapeutic attenuation of pleasure.

First popularized in 2019 by California psychiatrist Dr. Cameron Sepah, dopamine fasting has found some support in medical communities as a potential framework for behavior modification. So too is its conceptual language borrowed by cultural commentators who criticize the reduction of art, communication, and relationships to forms that provide immediate reward. But the concept remains most popular in the tech industry, where it finds a natural home among those who seek to “hack” their biology in the service of performance at work.

Scrutinizing this practice sheds light on the unreasonabless of the neurocentrism that currently grips American society. In the first place, because dopamine fasting is ironically unscientific. No research supports the idea that one could temporarily fast from all stimuli that activate the mesocorticolimbic reward system—which releases dopamine—and thereby reset its neurotransmitter receptors. Indeed, dopamine does not undergird our feelings of pleasure at all. Instead, this pathway serves another and much broader role in neural functioning: it permits our estimation of the expected value of a reward and our processing of prediction errors.

In other words, dopamine signals a current dissatisfaction that animates our motivation and our ability to learn through experience. And because of reciprocal connections with the frontal cortex, the seat of our higher cognitive function, this does not just apply to intrinsically rewarding stimuli like cocaine, food, and sex, but any object we judge or believe to be valuable. Dopamine is therefore likely implicated in any daily action one could perform—including the act of fasting itself.

A true dopamine fast would eliminate our capacity for any goal-directed behavior and freeze us in time. Indeed, mice depleted of all dopaminergic signaling show no interest in eating and will starve to death. Human patients with pathologies of the mesocorticolimbic system commonly show a blunting of motivation, attention, and memory, as well as stiffness, slow movement, and trouble with speech. The reader may recognize these as the symptoms of Parkinson’s—which is, in fact, caused by the death of dopamine-producing neurons. In fairness, Sepah has defended his invention by clarifying that it does not aim to reduce levels of dopamine globally, but merely to reduce levels of dopamine produced by addictive behaviors. Nevertheless, in practice, it is both understood and employed with the neurobiologically incoherent end of “resetting” one’s dopamine signaling.

Together with its scientific incoherence, a second and more serious problem with dopamine fasting lies in its underlying philosophical anthropology. For the apparently exclusive rooting of this practice in science does not make it ideologically neutral. Instead, it permits it to serve as an effective vehicle for an implicit view of the human person—and in particular, of the human person’s embodied desire.

The first presupposition underlying dopamine fasting is that bodily desire is an optional element of life, an “add-on” that we can (at least temporarily) do without. If experienced at a moderate level, it can be a positive element of our experience. But our default state is one of excessive engagement with the objects of our desire, which enslaves us to cycles of habitual behavior that do not, in fact, align with our higher goals.

One immediately hears a faint echo of the Christian notion of desire, which emphasizes the importance of ordering one’s bodily appetites to the good through the virtue of temperance. And insofar as secular “fasting” is predicated upon an intuition of this truth, it will likely bear good fruit. But from here, the implicit philosophy that undergirds this practice takes a turn.

For the second presupposition is that the body is a tool for the will. Through the manipulation of brain chemistry, one can intentionally choose and shape the objects of one’s desire. And controlling our embodied nature in this way, we can achieve our own self-chosen ends—such as productivity or contentment. For it is personal choice that bestows unity on human experience and meaning upon embodied desire.

This somewhat gnostic yet technocratic view of the body resonates with other currents in contemporary culture, such as the reduction of mental illness to a brain disease or the manipulation of one’s chosen gender expression. Note that this approach to the body does not entail an overt denigration of it. On the contrary, it often unfolds with a kind of tenderness, an esteem for the body that (like the instinct for temperance) echoes the important truth that it is worthy of care. But the idea that the body is given, and therefore that its desires possess a natural meaning, is nowhere to be found.

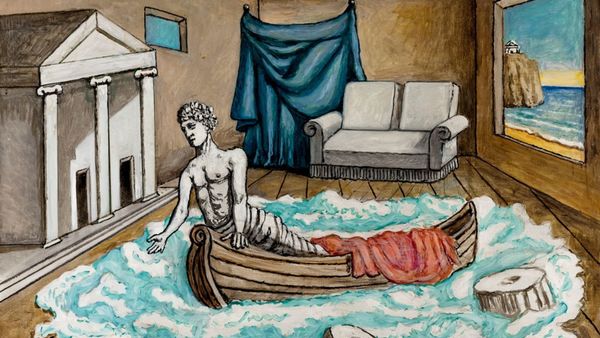

To see what is lost with the omission of givenness, it is useful to contrast this anthropological vision with the Christian claim: that the body is a sign and sacrament of a supernatural reality. If this is true, then the nature of the body—including its embodied desires—is given to us as the path to our fulfillment. Certainly, we do not travel this path by following our nature blindly or instinctively; to move from sign to mystery we must go to the depths of our experience. There, as the Dominican Conrad Pepler writes, we discover that “[we are] not satisfied with what satisfies the body,” and this dissatisfaction drives us to “[search] for something higher at the back of all [our] senses can know.”[3] The existential search, thus unleashed, does not relent until it seizes upon its true objects: perfect truth, love, justice, beauty.

But, crucially, the Christian does not leave bodily desire behind in walking this path. For perfect truth became incarnate. Perfect beauty has the appearance of the face of the fairest of the children of men, Jesus of Nazareth—a man who himself hungered and was satisfied. And the choice of God to enter the horizon of human history and pitch his tent among us continues in the Church, the mystical Body of Christ. Thus, the Father draws us to our destiny by physical and emotional, as well as spiritual, attraction to Christ (John 6:44). This method of God redeems the body. Indeed, St. Augustine called the freely extended gift of divine life the “victorious delectation”—in other words, a triumphant desire that wins through every other. Our task is therefore not to flee the body, but rather to work, as St. Paul noted, to find and adhere to him by “testing everything and retaining what is good” (1 Thess 5:21-22).

It is for this reason that asceticism, in the Christian tradition, has never primarily been a renunciation but the choice of a greater satisfaction. It is not primarily a negation but the affirmation of a truer good. Take, for instance, the virginal abstinence from sexual activity. This most natural expression of our human affectivity is given as a good, but the temporary renunciation of this good affirms that its meaning is greater than what is immediately apparent. Chastity allows the Christian to discover a deeper love of his spouse: a love that sees her not as an object but as a mystery, a sign given by the Mystery Himself who alone can truly fulfill each of their hearts. Even more radically, those who are called to this renunciation as a stable state of life discover through the path of virginity a nuptial relationship with that very Mystery, thereby anticipating and witnessing to the eternal wedding banquet that awaits all whom He draws to himself. The ascetic work of loving chastely is humanly fulfilling; it makes us whole.[4]

Accepting the givenness of the body, then, explodes the horizons of fasting—and indeed, of any renunciation. It serves not only to cultivate self-control and resensitize us to goods we take for granted, as secular fasting aspires to do. Rather, it promises a deeper possession of the very goods from which we abstain. For a true fast finds its meaning in the feast. Each step of growth in virtue thus deepens the bodily delight of the Christian—who even when she is old, is “still full of sap and still green” (Ps 92:14). Who does not long for such a life?

This alternative vision of desire is not only more compelling, but more coherent with the scientific study of the brain. For as the research cited above emphasizes, desire is the animating force of every human act; without desire, the human person does not live. While our embodied motivation is first moved by natural stimuli, it does not find satisfaction in them—and can even become enslaved if they are taken as its primary or exclusive end. But we cannot substitute the objects of our desire at will by distancing ourselves from bodily pleasures, as the secular fast would have it. Our neural structure is instead naturally oriented to the integration of our natural desires with our higher-order judgments and beliefs in an ongoing pursuit of something beyond. The form of the body reflects that we attain freedom through understanding the truth of the objects of our desire as signs of the infinite.

Perhaps then, our culture need not immediately leave behind its neurocentric gaze. Perhaps instead its inordinate fascination with the brain can serve as the path to a recovery of what stands at risk of being lost. In the case of dopamine fasting, for example, plumbing the depths of the study of the brain reveals a prophecy of the meaning of embodied desire: attraction to our destiny. As Luigi Giussani expresses it:

One phenomenon above all underlies the vibrant arc of human life . . . it is the common essence of every human interest, the driver of every problem: it is the phenomenon of desire . . . Desire, which is the expression of our human life, ultimately incarnates the profound attraction with which God calls us to Himself.[5]

EDITORIAL NOTE: The author of this essay will deliver a lecture on the brain in the 2024 - 2025 Organs and Origins Conference Series.

Inaugural Conference: What is an Organ? April 5 - 6, 2024 105 Jordan Hall of Science/Andrews Auditorium, Geddes Hall

The 21st century has witnessed amazing advances in the life sciences, especially in genomics, neuroscience, biochemistry and associated technologies. This rapid progress has led some scientists to have confidence in the human ability to engineer life, while inspiring others to see profound limits in the mechanistic modeling of living systems. How might interdisciplinary dialogue between biology, engineering, philosophy and theology frame and strengthen the latest insights into the nature of life?

[CLICK HERE for detailed conference info]

[1] See The Idea of the Brain by Matthew Cobb for a genealogy

[2] Defensio epistolae de propria conversion, 1680; cited in Andrew A. Sicree’s 2018 talk at the Society of Catholic Scientists on Steno entitled “Inside the Brain, Inside the Earth”

[3] Conrad Pepler, Sacramental Prayer

[4] See Erik Varden’s recent book Chastity

[5] Giussani, Risposte cristiane ai problemi dei giovani, p 127. Translation mine.