The joyful Easter season keeps us at play in the fields of solidarity, if we are willing to allow the celebrations to expand our sense of mutual belonging beyond Lent.[1] Prayer, fasting, and almsgiving extend our reach towards more radical forms of solidarity and awareness; as we pay closer attention to our own spiritual and bodily motions, we attune ourselves to the harmonies resonating in Creation: “For harmony is the unification of multiplicities and the agreement of those at variance” (Boethius). Indeed, our brains musically hum and come to match environmental rhythms.

The wisdom of orienting bodies, buildings, and liturgical motions in easterly directions arose in Christian tradition in part because of the sensed resonances of a grander cosmic liturgy in which planetary life is enfolded. Leaving Lent provides opportunities for extending participation in ancient traditions of character formation that changed us. We do well to consider extending practices just a bit, both in order to solidify habits and to extend our attentiveness to solidarity. Ramadan, for example, ends on April 9, thereby closely aligning interfaith practices for hearing the divine voice calling us to “hear” and respond in love (see the Shema of Deuteronomy 6 at the heart of the Torah).

I am suggesting we consider how our Lenten practices can take on the play-element of the Easter season and move us further into what I am calling the fields of solidarity. Frequently such practices are quickly jettisoned or forgotten, as with so many resolutions. If Lent renders us more aware of what Achille Mbembe calls our “planetary entanglements,” let us find ways to extend that awareness into our lives beyond Lenten solidarity. In what follows I shall share resources from anthropology, philosophy, and neuroscience to help us think about how we fit into this “common home.”[2]

Belonging in The Great Lakes Region of East Africa

If we imitated Christ’s desert wandering this past season, then we practiced theologies of harmony in line with the word from Boethius above. We may nevertheless be unaware of contemporary sources of attentive alignment of the person with the world one finds in anthropology, neuroscience, and philosophy. Attention is a good place to start.

How attentive are we to the ways our lives align or misalign with a theology of musical harmony? How aware are we of the degrees of the “planetary entanglements” that affect our mutual belonging? Over the past decade I’ve had the privilege of being at play in the fields of solidarity in Uganda, firstly by leading groups of students on university immersion courses, and secondly by engaging in research with priests and medical professionals at the intersection of religion and science.[3] I say “at play” to accent what Yala Kisukidi calls Laetitia Africana. “Writing a history of the African continent and Afro-descendant peoples based on laetitia [joy],” Kisukidi writes, “involves paying attention to sometimes minuscule and lusterless lives lived out despite the experience of devastation.”

Catholics might be aware of Pope Francis’s Amoris Laetitia (the joy of love) which continues Christian theologies of the everyday, the mundane, or the ordinary joys of life that are worth comparing to Kisukidi’s work. Accompanying excited and trepidatious students in immersion courses designed to create solidarity already creates conditions for sharing joy, and even more so the welcome offered by friends in the rich spirit of East African hospitality.

We arrive at the shores of Lake Victoria in Entebbe having prepared ourselves in the subjects of Christianity in Uganda, HIV/AIDS and infectious disease, as well as global health administration, so they are primed to make real what they have thus far imagined. Both as a respite from the psychological strain of learning practices of accompaniment and as a joyful sharing in the beauty of the Pearl of Africa, we take the students to Queen Elizabeth National Park at the western border of Uganda with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, home of tree-climbing lions and host to one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world. We stay one night in Mweya set at the end of the peninsula of the Kazinga Channel. Where we stayed there are no fences for keeping animals apart from human living quarters, so we walked and dined among warthogs and elephants moving freely.

That freedom of movement also brings along lions and hippos (the latter being the most dangerous of the “Big Five”). The one night we had perched above the Channel we received news (and heard the sounds) of lions on the hunt, and we all huddled together in my cabin, along with a swarm of other insects that made my mostly-urbanite students very nervous (luckily the bats hadn’t found our insect stash), not to mention the amplified fear-factor of having local guides also huddled with us carrying kitchen knives, just in case (!). I was the lone faculty leader that night of 30+ students, and the only thing that came to mind for calming the crew was a method I often used to put my children to sleep when they were young, namely the intoning of the Salve Regina.

The solo-performance set everyone at ease and we slept well after careful guidance back to the two adjacent cabins—we did all wake in the night to a herd of elephants out our windows, huddling together, and with us, seeking protection from the lions. That huddling is mirrored when you visit the Kazinga Channel and see all the animals down at the water during the day, crocodiles lounging beside hippos, and elephants beneath the watchful eyes of the African Fish Eagle (Haliaeetus vocifer). Reminders that we need to mindfully adopt ways of life for mutual belonging in our “common home” rest in the imagination differently after co-mingling with elephants seeking shelter.

Belonging Amidst Planetary Entanglements

The East African country is land-locked but shares the shores of Lake Victoria with Kenya and Tanzania; it is one of the lakes visible from space. A good example of Mbembe’s terminology of “planetary entanglement” is found in the award-winning documentary film Darwin’s Nightmare (2004).[4] The film teaches viewers about the introduction of the Nile perch (lates niloticus) in the 1950’s by colonial powers to create another abundant food source for the area. The Nile perch is an invasive species and although it created a brief economic boom, the film tells how that boom left Tanzanians starving as European planes flew out the perch for their markets, while flying in weapons in a tangled exchange. Jim Proctor helpfully diagrams the entanglements of Darwin’s Nightmare to teach readers how to understand Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory (ANT) so that we can follow the different ways supply chains can be analyzed and presented (Mapping Actors and Processes).

When we consider the networks of planetary entanglement from this angle, we become more critical of the phrase “economic boom” when we see beyond simple economic valuation for German GDP with its uptick for a new perch market and rather see the unhoused alongside the sex workers of Mwanza for what they are: members of economic inclusion designed to dehumanize (more on this below). Something similar happens when we consider the increased disease burden of the fishing villages across Lake Victoria from the vantage-point of the Rakai Health Sciences Center, an HIV/AIDS and infectious disease research center we normally visit in our immersion courses. As they have shown, disease burdens are much higher along migration and work patterns within Lake Victoria, in part because many of those fishing feel that they are more likely to die from an accident in the waters than by infectious disease.[5] It is likely readers are not eating Nile perch and further fueling these patterns. Yet, our Lenten practices render us mindful of complicity in systems that keep us at variance with ourselves and our environments. Drawing on decades of environmental activism and discard studies, Doherty argues that the

Assertion that there is no such place as Away is intended to make visible the geography of disposal, to refute the economic calculation of externality that casts these places aside, to insist on the existence and densely inhabited nature of these places, and to ensure that they are accounted for in the ethical, political, and environmental imagination.[6]

The insights complement and alter Pope Francis’s use of the phrase “throw away” culture wherein human beings “are themselves considered consumer goods to be used and discarded” (Evangelii Gaudium, par. 53).[7] The further complement Doherty offers concerns the challenge that concepts of disposability and discardability hide the reality that what we have is simply another form of inequity:

Disposability is best understood not as an existential condition of social exclusion but as a form of inequitable social inclusion that combines investment and material abandonment, functional dependence and legal criminalization, care and blame…Disposability is an infrastructural condition.[8]

We can address such infrastructural conditions by becoming aware of the complexities of our waste worlds and changing our behaviors.

The Brain-Gut-Biome (BGM) and Neuroplasticity

Regarding consumption more generally, consider too the importance of the brain-gut-microbiome (BGM) for Lenten restoration’s ways of working healing into everyday challenges at once personal and planetary that can be expanded beyond the usual forty days. Paying attention to what and how we eat can help or hinder the brain’s ways of healing itself. Diets increasing inflammation can adversely impact brain health. “There is a close link between immune activation in the gut and neuroinflammation in the brain, as the gut microbiome can directly influence the maturation and functioning of microglia in the CNS [central nervous system] as part of the immunoregulatory pathways” (Horn et al.). Although many of us reach for medicines to address health irregularities, a return of the “food is medicine” trend with anti-inflammatory additions to consumption addresses human and planetary health simultaneously by focusing on plant-based sources of nourishment.

Additionally, much less waste is generated from increasing plant-based sources, even more so if we can find ways to source locally. Prayer, fasting, and almsgiving detach us from unhealthy dependencies and attune us differently to the cry of the earth amidst our planetary entanglements. Can we see, can we hear, the cries of our waste worlds? If we eat differently, even our Gut Microbiome-Brain Axis changes and perhaps we become attentive to the places from which our food arrives.

Recent studies on the BGM show that human attentiveness is impacted by what we eat, how we move, and even what we hear. I talked about singing the Salve Regina as a primer for appreciating neuroplasticity from the direction of sound therapies. Just as the BGM can heal itself through treating food as medicine, so too can the BGM be healed through sound and movement therapies that may share commonalities with Lenten practices across traditions. “The music in sound therapy,” writes psychiatrist Norman Doidge, “turns on and enhances the connection between brain areas that process positive reward (which give us a feeling of pleasure when we accomplish something) and the insula, a cortical area of the brain that is involved in paying attention.”[9] Movement therapy acts similarly on the ability to pay attention because the cerebellum is involved. “To pay attention to one thing requires inhibiting the temptation to attend to something else.”[10]

Literature on neuroplasticity fortunately suggests that deliberate practice can help those who struggle with paying attention to develop new capacities for attentiveness. As we shall see, if we include recent science on the Gut Microbiome-Brain Axis, we are further on our way toward the kind of systems thinking uniting us in mutual belonging to wider networks of social belonging, including the cosmic whole in which we are harmonically resonating (see also: The Artful Brain).

The Case of the Monks of the Abbaye d’En Calcat

In the tradition of Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, with its intoning of “Wisdom! Let us be attentive,” let us remain with Doidge for a moment. Catholics will be interested, I think, in the way he connects neuroplasticity and healing therapies to the case of the monks of the Abbaye d’En Calcat in the Tarn of southern France. (Caveat emptor: the use of the example here claims no critique of Vatican II and its implementations on the part of this author, but serves rather to highlight the therapeutic neuroscience available to us today in a context of interdisciplinary meditation.)

The pioneering work of Alfred Tomatis (whose innovations in movement and sound therapy some may know by the simplified and often erroneous ways his “Mozart Effect” is applied in popular culture and child development), introduces readers to this. Tomatis was called to assess an Abbey filled with ill monks. Suspecting an infectious disease outbreak, he rather found that a “zealous young abbot” had decided to end Gregorian Chant from his reading of Vatican II (1962-65). As they had been chanting six to eight hours a day for their lives, most of the monks found the change uninhabitable. Tomatis slowly reestablished their singing, first through individual therapy that included chanting into an electronic ear that resembled the soundscape of the monastery, and then by reuniting the monks to chant together once again.

While doing the work, Tomatis participated in the chanting and testified that chanting charges the body like two cups of coffee; during that time he too slept only four hours a night but felt charged by the enchanting ora et labora patterned life.

The rhythm of the chant often corresponds to the respiration of a calm, unstressed person, and it has an immediate calming effect—probably by entrainment. Entrainment is a process in which one rhythmic frequency influences another, until they synchronize, or approach synchronization, or have a strong influence on each other.[11]

I can share personally that I teach an immersion course in Uganda for undergraduate students where we experienced together something of this calming effect, and practiced it in the illustration of the students and the lions at the beginning of this piece.

Such encounters also return us to ourselves and (for some) to God. “The world is charged with the grandeur of God,” G.M. Hopkins wrote in God’s Grandeur. The term “charged” is used to good effect by the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor who uses it to invoke the more ancient traditions of the “enchanted world” mostly in decline today. The majesty of the wild animals instills awe, wonder, and reverence. Beholding them is absorbing. One falls attentive. As the French friar Eloi Leclerc (1921-2016) puts it: “If we knew how to adore, then nothing could truly disturb our peace. We would travel through the world with the tranquility of the great rivers. But only if we know how to adore. Of course, adoration is finally the response to something Perfect. But the genius of love is that it teaches us how to give ourselves to imperfect things too. Love, you might say, is the training ground of adoration.”[12] We require such training in love through our landscapes and our soundscapes in order to sustain hope amidst the sorrows present when at play in the fields of solidarity.

Absorption, Porosity, and Enchantment

In a recent five-country study of human openness to religious experience, the kind where God or other spiritual entities can be encountered, Tanya Luhrmann et al. used a method of assessing such openness using various methods, including a psychological measure called the “Absorption Scale.” The questionnaire helps researchers assess “an immersive orientation toward experience.” They found that the greater the capacity for absorption in activities generally, the greater the kinds of openness one finds in religiously-affiliated people.[13]

My own collaborative work views absorption as an immersive style of attention, a personal orientation toward one’s own mind, that varies across individuals, independent of cultural models of the mind. In our theory, absorption facilitates a sense of spiritual presence because many apparently supernatural events emerge when people attend differently to the world: they use their imagination to understand something beyond the here-and-now, to watch for signs of the presence of a being that cannot be seen. As people become absorbed, their practical concerns recede and their immersion increases.[14]

As you surmise, my work is about Theory of Mind (ToM). Absorption can be directed towards one’s mind or the minds of others (social science refers to those involved in one’s network beyond the “ego” as “alters”). Depending upon how capacious or limited one’s social imaginary may be concerns what is available in terms of alterity[15] (in a positive sense). People with that more capacious and expansive networks of belonging fall within the category of “porous” selves, in the language adopted from Charles Taylor.

Porosity is a term used across disciplines, from describing a molcajete bowl to cell structures. For Taylor, and in similar ways for the philosopher William Desmond, porosity concerns the capacity for human openness to transcendence. Traditionally something of the sort went by the name of Capax Dei, to be capable of God, if not on one’s own, then assuredly in networks of belonging tethering the person to community, creation, and God. Although the capacity is present, the completion of that capacity requires the gift of God’s grace, arriving to a self with porous boundaries through which the divine becomes present.

Luhrmann’s study combines the absorption scale with a “Porosity Scale” to assess the range and degrees of openness (my term). The difficulties people have today with taking this seriously, and with allowing comportment to God to include (as it were) Franciscan spiritualities of “Sister Son, Brother Moon,” speaks to the contemporary “buffered” self, living in a world devoid of the agency and activity of one “charged with the grandeur of God.” As Taylor puts it, “Charged objects have causal power in virtue of their intrinsic meanings.”[16] We are amidst a global revival of an interest in the “intrinsic meanings” of creation in response to the use and destruction of all “things” in a logic of late capitalism unable to imagine another mode of value beyond market price.

The Taylor-inspired research of Luhrmann, Balcomb, and now that taking place through The Human Network Initiative at Harvard Medical School where I serve as Co-Principal Investigator, all provide evidence that so-called porous selves are alive and well in the world, suggesting that most humans carry within themselves a variation on the buffering/porosity divide. We are all subject to contending modernities. We see it all over Uganda amidst the pressures of the planetary entanglements I have already mentioned. What will become of the relationships to ancestors held so sacred, a connection frequently tied to land and location, where urbanization pressures, sourcing of petroleum from Murchison National Park, and the coming of Starlink further solidify new forms of empire?[17] Amidst the rapid changes, there are nevertheless resources for re-enchantment poised for new forms of porosity.

Prayer and Global Grammars of Animacy

Witness the rise of environmental personhood and the rights of rivers. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass marshals a scientist’s clout with indigenous wisdom to present a new case for a “grammar of animacy.” Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator, SJ, Dean of the Jesuit School of Theology at Santa Clara University (Berkely Campus), argues for a renewal of a Catholic “animism” that recovers lost wisdom from the continent of Africa, in places as diverse as Nigeria and Uganda.[18] He says that, “Wisdom from traditional African Religion sets it apart from the dominant approaches in the Judeo-Christian traditions but also complements them. A first principle is that the earth, our mother, is the outcome of an intentional act by an agent who is deeply involved and invested in the process of creating the world and human beings.”[19] Echoing Acts 17:28, Orobator shows how a more capacious sense of porous belonging, present in the social networks of many African communities, provides resources for earth-renewal from a perspective that wants to push human capacities for absorption and porosity beyond Feuerbachian projections of unbounded imagination and into the domain of existential engagement with neurological implications on the patterning of neural pathways.

A theology of harmony alluded to above requires a robust account of renewed realism, in the spirit of Bruno Latour’s studies, in order to give the porous imagination a wide berth in “Waiting for God” that is chastened by evidence. Perhaps we are finding a new way to engage in negative theology, by way of interdisciplinary learning and collaboration? Even the late Marshall Sahlins published a book continuing the conversation on enchantment within the anthropological guild (see: The New Science of the Enchanted Universe: An Anthropology of Most of Humanity). Perhaps we can venture some risks in the co-learning process and allow the wisdom of Simone Weil to guide our “research studies” rather than simply our “school studies.”

In “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God,” Simone Weil unites the languages of love and lament through her concern to communicate her love of scholarship and her lament at falling short. Simone was a gifted scholar who loved intellectual craft-work but who nevertheless lamented her inability to match her brother’s mathematical genius; André Weil spent 30 years at the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton) alongside Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, John von Neumann, and Kurt Gödel.

“The key to a Christian conception of studies,” writes Weil, “is the realization that prayer consists of attention. It is the orientation of all the attention of which the soul is capable toward God. The quality counts for much in the quality of the prayer. Warmth of heart cannot make up for it.” What Weil called the “muscular effort” of learning is a dead end; we cannot simply apply more energy, but must rather let go and empty so that we are ready to receive the “charged objects” in their ability to communicate to our preparedness. “Our thought should be in relation to all particular and already formulated thoughts, as a [person] on a mountain who, as he looks forward, sees below him, without actually looking at them, a great many forests and plains.” The progression she envisions takes one through the process of paying close attention to studies in order (1) to learn from mistakes with an openness to moving through them without allowing them to damage consciousness too greatly, so that (2) an attentive openness to other people becomes natural and welcoming, especially in their affliction (likely mathematically induced, in her mind), so that (3) the capacity to meet God (the capax Dei) is practiced habitually, enabling the one waiting to recognize a world “charged with the grandeur of God.”

Weil’s short essay reminds me of the opening of Abraham Heschel’s preface to the Prophets, vol. 1. After telling how he left philosophy for the biblical prophets, and some reflections deserving a more robust comparison to Bernard Lonergan’s notion of “insight,” Heschel objects to treating anything studied as dead objects to the mind and rather urges a phenomenological suspension of his own: “The situation of a person immersed in the prophets’ words is one of being exposed to a ceaseless shattering of indifference, and one needs a skull of stone to remain callous to such blows.”[20] Heschel anticipated Pope Francis’s emphasis upon the shattering of indifference by decades, foreshadowing “interfaith affinity” on such matters haunting modern imaginations. Are we listening and attentive to the cry of the earth, the cries of those to whom we belong? Grammars of animacy, and their notes on re-enchantments of a world otherwise everywhere for sale, are already in use by those seeking change.

Conclusion

The Easter season bridges the desert wandering to a return to the ordinary by way of joy. Carrying Lenten practices across the bridge can solidify habits nascently formed so that they enter the ordinary and increase attention, absorption, and porosity so that we are more capable of receiving the divine guest when occasions arise. Either through acts of prayerful imagination or lived experience we can be at play in the fields of solidarity. In the language common to contemporary neuroscience, our cognitive and limbic anxieties can be calmed through a fabric of musical harmony and imagination invoked in community. As we seek new ways of living together well, perhaps new Catholic grammars of animacy rooted in joy can contribute to modes of belonging beyond Lent and keep us at play in fields of solidarity.

[1] For a short intellectual history of “play” as applied to liturgy, and some attendant problems worth considering, see Gschwandtner, Christina M. 2021. "Is Liturgy Ludic? Distinguishing between the Phenomena of Play and Ritual" Religions 12, no. 4: 232. (https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040232). A valuable contrast, however, would be to that of Elochukwu Uzukwu, “Liturgy, Culture and the Postmodern World: Echoes from Africa,” Explorations in Faith and Culture: City Limits- Mission Issues in Postmodern Times, edited by Joe Egan and Thomas Whelan (Dublin: Milltown Institute of Theology and Philosophy, 2004), 162. I have danced with Christian communities in southwestern Uganda, among the Bakiga, and the ludic is melded with lament deeply tied to cultural traditions of mutual belonging. See also Francesca Aran Murphy, “From Play to Freedom: Robert Bellah Puts Creative Freedom at the Heart of Human Nature,” First Things, June 2013.

[2] A Greener Lent helped many re-orient their daily practices towards planetary well-being, further contributing to the mounting evidence for “Religious fasting and its impact on individual, public, and planetary health: Fasting as a “religious health asset” for a healthier, more equitable, and sustainable society.”

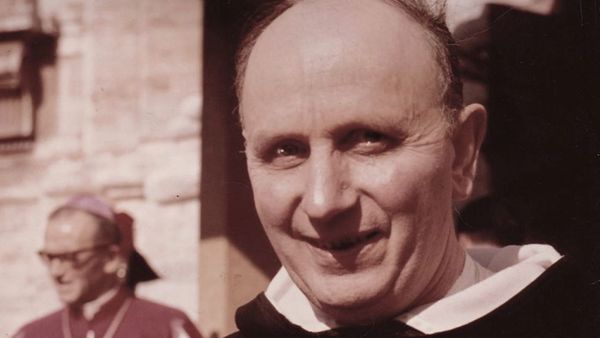

[3] See my piece on the important work of Br. Fr. Anatoli Wasswa, for example.

[4] The term “entanglement” is fittingly indebted to Charles Darwin who ends his Origin of Species (1859) with the metaphor of the “tangled bank”: “It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms ... have all been produced by laws acting around us...” See also Stanley Edgar Hyman, The Tangled Bank: Darwin, Marx, Frazer and Freud as Imaginative Writers (1962).

[5] See Kate Grabowski, M., Lessler, J., Bazaale, J. et al. Migration, hotspots, and dispersal of HIV infection in Rakai, Uganda. Nat Commun 11, 976 (2020). (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14636-y)

[6] Jacob Doherty, Waste Worlds: Inhabiting Kampala’s Infrastructures of Disposability, (University of California Press, 2021), 80.

[7] See also Clark, C.M.A. and Alford, H. (2019), The Throwaway Culture in the Economy of Exclusion: Pope Francis and Economists on Waste. Am J Econ Sociol, 78: 973-1008, here 976.

[8] Doherty, Waste Worlds, 25.

[9] Norman Doidge, The Brain’s Way of Healing, (Penguin Random House LLC, 2015), 338.

[10] Doidge, ibid., 340-341.

[11] Doidge, ibid., 345.

[12] Richard Rohr, The Universal Christ.

[13] See Luhrmann, T.M. (2011), “Hallucinations and Sensory Overrides,” Annual Review of Anthropology 40, pp. 71-85. Luhrmann, T.M. (2012), “Beyond the Brain,” Wilson Quarterly 36(3), pp. 28-34. Luhrmann, T.M. (2017), “Knowing God,” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 35(2), Special Issue – Infrastructures of Certainty and Doubt, pp. 125-142. Luhrmann, T.M. How God Becomes Real: Kindling the Presence of Invisible Others. Princeton University Press. 2020. Luhrmann, T. M., & Weisman, K. (2022). Porosity Is the Heart of Religion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(3), 247-253. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214221075285

[14] Luhrmann et al., “Sensing the presence of gods and spirits across cultures and faiths,” 7.

[15] This usage is not in the pejorative sense of “othering” in dehumanizing contexts, but rather in terms of the non-self to which one may be variously tethered.

[16] Taylor, A Secular Age, 39.

[17] See Vili Lehdonvirta, Cloud Empires: How Digital Platforms Are Overtaking the State and How We Can Regain Control (MIT Press, 2022).

[18] See Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator, SJ, Religion and Faith in Africa: Confessions of an Animist (Orbis, 2018).

[19] Orobator, Religion and Faith in Africa, 108-109.

[20] Abraham Heschel, The Prophets, vol. 1 (Harper, 1955), xii.