Introduction

For the better part of the twentieth century the name Bishop Fulton J. Sheen was synonymous with American Catholicism. The full impact of Sheen’s career and his influence upon the American Church will never be fully determined—and perhaps never fully appreciated. During his lifetime Sheen authored sixty-six books, published over sixty Catholic pamphlets and booklets, delivered weekly radio broadcasts for over twenty years, wrote countless syndicated articles and columns, edited two magazines, instructed thousands of converts to the Catholic faith, raised over $100 million[1] for the Society of the Propagation of the Faith[2] while serving as its director from 1950–1966, and participated in every session of Vatican II.[3] His influence on the twentieth century American Church can hardly be overstated.

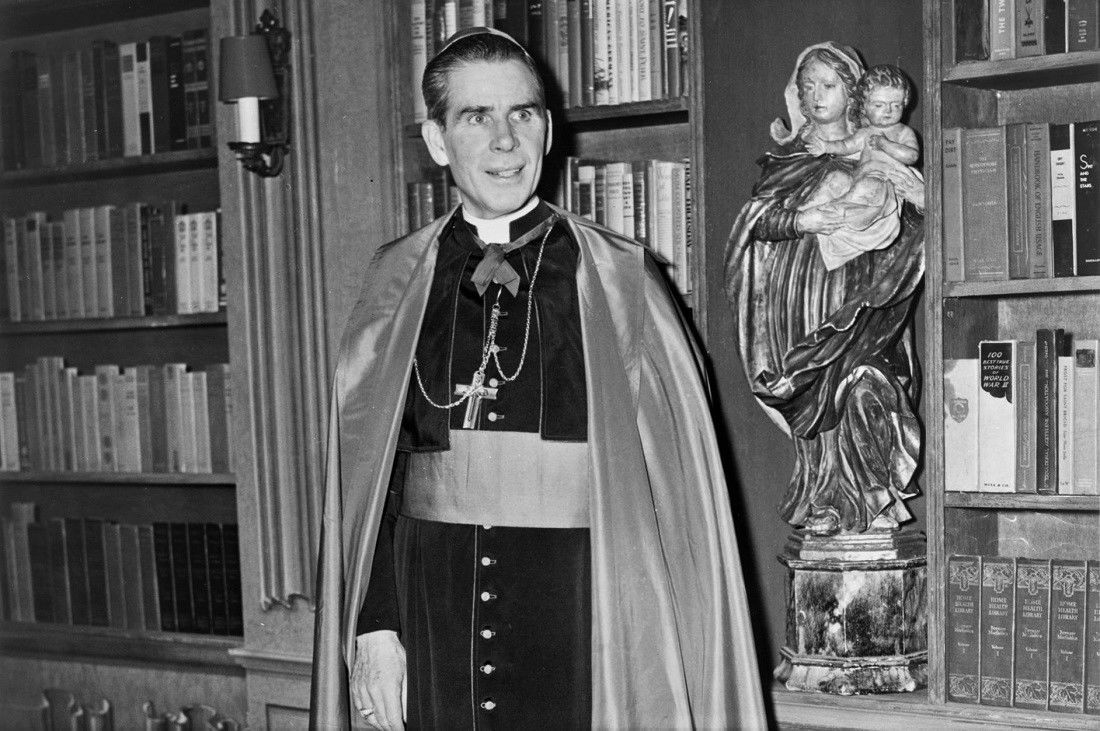

Sheen’s rise to fame in American culture accelerated in 1930 when he agreed to deliver weekly addresses for the newly minted radio broadcast The Catholic Hour. Sheen’s popularity reached its peak in the 1950s when he was offered his own television show, Life is Worth Living, which ran for five seasons from 1952–1957 during prime time. At 8:00 p.m. on Tuesday evenings, Bishop Sheen, donned in full episcopal regalia and his trademark purple ferraiolo (episcopal cape), would appear before the cameras and his live audience to deliver an uninterrupted lecture that was exactly twenty-seven minutes and twenty seconds in length, the full duration of his scheduled slot. Over the course of the show’s five seasons Sheen lectured on a wide array of topics including philosophy, science, politics, Communism, psychology, religion, the meaning of life, and topics, as Sheen described, more “ecumenical in nature” that were intended to appeal to “Catholics, Protestants, Jews and all men of good will.”[4] During the height of the show’s popularity Sheen was reaching an estimated 30 million viewers.[5] So beloved was Sheen in the culture during this time that in 1952 he received the Emmy Award for “Most Outstanding Television Personality.”[6]

Much has been written about Sheen as of late. His popularity in the American Church is seeing a resurgence and many of his books are being republished as interest in his writings and his distinctive style continues to grow. His cause for canonization was officially opened in 2002 and is advancing at a steady pace. Benedict XVI[7] declared Sheen “Venerable Servant of God” in 2012 and on July 6, 2019 Pope Francis formally approved a miracle attributed to Sheen setting the stage for Sheen’s beatification and—God willing—his canonization.

Many of those writing about Sheen often focus on his spirituality and rigorous prayer life. Others concentrate on his unparalleled evangelical efforts, citing the countless number of those who joined the Church because of their encounter with Sheen.[8] An entire chapter of his autobiography, Treasure in Clay, is devoted to his time working with converts. Thomas Reeves, author of the most exhaustive biography on Sheen published to date, notes that Sheen once told an interviewer, “I can say that I prefer the instruction of souls to any other work I do.”[9] Sheen was the leading evangelizer of his time and is now an icon for many who are currently engaged in the Church’s work of evangelization and catechesis. Bishop Robert Barron, a man often compared to Sheen for his media-driven evangelization efforts, has called Sheen “the patron saint of media and evangelization.”[10]

One area of Sheen’s life, however, that rarely receives due coverage is the teaching career and scholarship that predated Sheen’s popular writings and television career. Sheen taught as a full-time professor at The Catholic University of America from 1926-1950, first in the School of Theology and later in the School of Philosophy. At the start of his teaching career, which began shortly after completing his Ph.D. and the prestigious post-doctoral agrégé degree[11] at the University of Louvain, Sheen was regarded as one of the premier Thomistic scholars of his time. The illustrious “super doctorate” degree that Sheen earned entitled him to full professorship in the School of Philosophy at Louvain. Sheen would have accepted such a position had his home bishop not promised him to the faculty at Catholic University. Catholic University was particularly fortunate to add Sheen to its faculty in 1926 because this was precisely the time when Sheen’s esteem within the worlds of academic theology and philosophy skyrocketed. The publication of his 1925 book, God and Intelligence in Modern Philosophy: A Critical Study in the Light of the Philosophy of Saint Thomas, garnered Sheen extraordinary respect in the academy for his scholarship on Thomas Aquinas. The book was so well received that Sheen was awarded the Cardinal Mercier International Philosophy Award for it. This award was given out only once a decade; Sheen was its first ever American recipient. Impressed, too, with the text was G.K. Chesterton, whose admiration for it is evidenced by his willingness to write the text’s introduction.[12] Four years later, in 1929, Sheen was elected secretary-treasurer of the American Catholic Philosophical Association; he went on to serve as president of the organization in 1941, a sure sign of his arrival as a respected contributor to twentieth century Thomistic thought.

Today, Sheen’s intellectual abilities are rarely contested, but he is seldom celebrated for his contributions to scholastic philosophy and for his impressive university teaching career. His writings from these years showcase a kind of rigor and breadth of thought not generally associated with Sheen today. In what follows I would like to focus on one area of Sheen’s early thought that is rarely, if ever, discussed: his philosophy of education. Sheen was a tremendous advocate of the Catholic system of education—in fact, he believed that it was the only truly worthwhile system of education in the world.

Sheen’s philosophy of education is perhaps best contained and articulated in his essay, entitled “Education and the Deity-Blind,” which appears as a chapter in his 1931 book Old Errors and New Labels. Working within a Thomistic framework, Sheen espouses a view of education that is rooted within the nature of the human person as a rational creature capable of knowledge of God as his final end. Given that today many Catholic institutions—academic and otherwise—struggle with a sense of Catholic identity, or with the supposed difficulty of articulating what exactly is gained by remaining rooted in the Catholic theological and intellectual tradition, Sheen’s attach on religious education is particularly relevant. My aim in laying out Sheen’s philosophy of education is twofold. First, I would like to call attention to Sheen’s earlier, more philosophically-geared—and regrettably, overlooked—writings. Second, I would like to advance what I believe is a powerful and systematic argument for the inherent meaningfulness of the Catholic system of education. In doing so, I hope to provide something of a response for those in the Church who are tasked with making a compelling case for religious education today.

Sheen’s Philosophy of Education

Sheen’s view on education is rooted in his understanding of the meaning of life and in the nature of the human person because Sheen thinks that education is always contingent upon the subject being educated. Working within an Aristotelian and Thomistic framework, Sheen contends that life in its simplest expression is activity, or “adjustment to environment.”[13] Sheen suggests that there is a universal principle governing the hierarchy of life found in nature: the higher the form of life, the greater the ability for activity. He thinks that as one examines the hierarchy of life found in nature one will notice a change in activity, or ability to adjust to one’s environment. Sheen calls this ability “plasticity.”

In Sheen’s view, lifeless objects, like basic elements and chemicals, have no plasticity; they cannot, by themselves, adjust to their environment. Plants, however, containing within themselves a higher form of life, are capable of adjusting, albeit in a limited way, to the introduction of rain, cold, warmth, sunshine, for example, into their environment. Similarly, animals, containing within them a still higher form of life, are endowed with an even greater degree of plasticity. Using knowledge gained from sensory data, animals can move about their environment seeking nourishment, protection, and even rest. Moving beyond animal life, one arrives at human life, which, Sheen claims, is infinitely plastic.

Humans, unlike animals, are not only capable of movement about their environment but also of movement into themselves where rational consideration of their environment, and of their very own existence, is possible. The human person ponders, questions, studies, self-reflects, and recognizes within himself an infinite desire for things such as life, truth, love, and beauty—concepts utterly foreign to lower forms of life. The human person, Sheen contends, expresses a desire not just for some life, but rather for infinite life; not just for some degree of truth, but for infinite truth; not just for some love, but for infinite and never-ending love. The human person, Sheen writes, “alone of all creatures on this earth has the possibilities of attuning himself to the infinite.”[14]

In addition to his ability to abstract to and long for the infinite, Sheen thinks that the human person is uniquely situated to take in and comprehend the whole of his environment and the very meaning of its existence.[15] This is to say that the human person is a creature that naturally and rationally seeks causes and ends. In knowing the cause and end of a thing—a kind of knowledge not found in lower forms of life—the human person knows not only what that thing is and how it is, but also why it is and for what it is. The human person not only works to make the universe his home, but he also subjects it to his reason; that is, he seeks to comprehend it, to make sense of it, to order it, and to articulate a narrative that can accurately describe it and the meaning of its existence. Elsewhere, Sheen calls the human person a kind of microcosm, for he alone in all of creation is capable of comprehending the universe; that is, he is capable of getting the whole universe to exist inside his mind.[16]

Illustrating this idea, Sheen compares the human person to a man in a boat in the center of a lake who notices a series of ripples that have long been widening until they have at last reached and splashed the side of his boat. “Now the man in the boat,” who is capable of moving from the effects to their cause, “knows that the ripples did not cause themselves. If he is to account for their existence he must look out beyond to the distant shore where perhaps stood a man who threw a stone into the lake that caused it to awake with its watery vibrations.”[17] In a like manner, Sheen supposes that there lies deep within the human person a desire for some account that can make sense of the totality of his environment—an account that can explain the existence of the various ripples of being that make up his universe. Plants might adjust to a continuous and steady influx of ripples, animals might seek sensory understanding of this or that ripple, but only humans desire, and are capable of, a complete explanation of those ripples—which includes the meaning of their existence.

With these two premises in mind—that the human person is capable of abstracting to and yearning for the infinite, and that the human person is naturally disposed toward comprehending the whole of his environment—Sheen offers his philosophy of education. He writes:

Education cannot be understood apart from the plastic nature of man. Taking due cognizance of it, one might say that the purpose of all education is to establish contact with the totality of our environment with a view to understand the full meaning and purpose of life.[18]

For Sheen, the meaning and purpose of life cannot be understood apart from God, nor, he writes, “can anyone enter into contact with the whole of environment unless he enters into relationship with God.”[19] God, on Sheen’s view, is the Infinite that alone makes sense of the infinite desires of the human heart. As the first cause, God is the source of the intelligibility of the universe and the ultimate explanation of its existence. Without God (the cause), the universe (the effect) goes unexplained and the human desire to know and understand the whole of his environment is frustrated. This, in turn, leads Sheen to claim that when God is removed, true education—that is, education that takes stock of what the human person really is—becomes impossible.

If the human person is by nature a creature attuned to seeking causes and ends, and if God is necessarily the cause and the end of the whole of the human person’s environment, then the only form of education suited for the human person is one that necessarily asserts God, or is least predicated upon God, as a first principle. Any form of education not tethered to God, Sheen thinks, will ultimately frustrate the desires of its students by denying them “the right to know the totality of all environments and the reason of it all, which is God.”[20] An education that fails to acknowledge God necessarily limits a student to only part of his environment. Students educated in this way are, therefore, robbed of true education—they are given no understanding of the whole. They may come to knowledge of this or that ripple of being, but they will surely have no ultimate knowledge of why the various ripples of being exist or of the final end of those ripples. These students, Sheen suggests, advance in life with only an imperfect understanding of the world and of their purpose therein. Sheen writes:

Are the schools and universities throughout the country that ignore God really educating the young men and women entrusted to their care? Would we say that a man was a learned mathematician if he did not know the first principles of Euclid? Would we say that a man was a skilled littérateur if he did not know the meaning of words? Would we say that a man was a profound physicist if he did not know the first principles of light, sound, and heat? Can we say that a man is truly educated who is ignorant of the first principles of life and truth and love—which is God?[21]

Students, however, educated in the Catholic system of education—the very system which shaped Sheen’s view of God, life, the human person, and education—are capable of arriving at the meaning and purpose of life. They can, Sheen argues, make sense of “those concentric orbs of knowledge which make the ripples of the universe” precisely because they have arrived at “the Hand that created those ripples in the immensity of space.”[22] These students can be said to be truly educated:

They who have been educated in the sense in which I have defined, are the only ones of all university graduates who know why they are here and whither they are going. The least that can be expected of any college or university is that when it embarks its graduates upon the sea of life it will furnish them with a compass with which they may find their port. Students of Catholic colleges have been given this compass, which is their faith. They have been steered toward their port, which is the Kingdom of God . . .[23]

Without God any system of education is necessarily incomplete. It is this view of education that animated Sheen’s teaching career and his methods in the classroom. Sheen was absolutely convinced that his students—and everyone with whom he came into contact—deserved to know that they were not only capable of coming to know the particulars of their environment but also of understanding the meaning behind its existence: God. For this reason, Sheen considered teaching to be sacred, a process capable of communicating the divine at any turn. In his autobiography he describes teaching as a participation in the “prolongation of the Divine Word,” making it “one of the noblest vocations on earth.”[24] In one episode of Life Is Worth Living Sheen stated that teachers are “custodians of the truth” and that they, for their efforts in shaping “young minds [and] young wills in the way of truth and goodness,” will “shine as stars for all eternity.”[25]

Sheen’s confidence in the meaningfulness of education—rooted in having God for its end—is unmistakable and helps make sense of the seriousness displayed in his teaching style and the rigorousness that marked his pedagogical methods in the classroom. His philosophy of education, however, is one that is not peculiarly his own. Sheen echoes a view that can be found in the thought of John Henry Newman, Jacques Maritain, and others. This is because Sheen’s conception of the human person is essentially Catholic, consistent with the Church’s long-standing view of human nature. He conceives of the human person as a body-soul composite, a being fundamentally oriented to God. “The human person, created in the image of God, is a being at once corporeal and spiritual,” declares the Catechism of the Catholic Church (§362). Therefore, the spiritual side of the human person, which the Church teaches to be “that which is of greatest value in him, that by which he is most especially in God’s image,” cannot be ignored in any system of education. This spiritual reality raises the human person above all lower forms of life, destining him to be, in Sheen’s words, “king of the universe” and “paragon of animals,”[26] or in the language of the Catechism, a creature ordered “to a supernatural end” (§367). When this supernatural end—communion with God—is forgotten, true education becomes impossible; when this end is recognized, true education may commence and the human being may at last realize the infinitely plastic ends of his nature.

[1] See Thomas Reeves, The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2001), p. 4, and Raymond Arroyo’s forward, “A Prophet Suffering in Silence,” in the 2008 edition of Treasure in Clay (Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay [New York: Doubleday, 2008], xii.

[2] Those who knew Sheen often note that he donated all of his earnings from his time on television to the Society for the Propagation of the Faith—Sheen was paid $26,000 per episode of Life Is Worth Living. Sheen once told a reporter that his personal contributions to the missions exceeded $10 million; others who knew him personally also support this claim. See Thomas Reeves, The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2001), 4, and Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay (New York: Doubleday, 2008), 67.

[3] Thomas Reeves, The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2001), 2-4.

[4] Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay (New York: Doubleday, 1982), 72.

[5] Sheen, Treasure in Clay (New York: Doubleday, 2008), xii.

[6] Reeves, The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen, 240.

[7] Interestingly, Sheen and Ratzinger worked together on the Commission on the Missions during the Second Vatican Council.

[8] Sheen personally instructed thousands, often in his own home, and the number of those converted by his books, radio and television broadcasts, and recorded talks is likely a staggering figure. See Reeves, The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen, 4.

[9] Reeves, The Life and Times of Fulton J. Sheen, 182.

[10] Sharon Otterman, “For a 1950s TV Evangelist, a Step Toward Sainthood,” The New York Times, June 29, 2012.

[11] The agrégé was a prestigious post-doctoral degree that Sheen was invited to work toward by the University of Louvain. The degree required a public examination before professors from multiple universities and the publication of a book.

[12] Sheen considered Chesterton one of his greatest influences. He writes, “The greatest influence in [my] writing was G.K. Chesterton, who never used a useless word, who saw the value in paradox and avoided what was trite” (Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay [New York: Doubleday, 1982], 79).

[13] Fulton J. Sheen, Old Errors and New Labels (New York: Alba House, 2007), 169.

[14] Sheen, Old Errors and New Labels, 169.

[15] Whether the human person does come to understand the whole of his environment is another matter. Sheen’s claim here is only that the human person by nature is capable of such knowledge.

[16] Sheen, Life is Worth Living, “How to Improve Your Mind.”

[17] Sheen, Old Errors and New Labels, 172.

[18] Ibid., 170.

[19] Ibid., 172.

[20] Ibid., 178.

[21] Ibid., 174.

[22] Ibid., 179.

[23] Ibid., 178.

[24] Ibid., 54.

[25] These are quotations from an episode of Life Is Worth Living, “Why some become Communists,” that Christopher Owen Lynch includes in his book Selling Catholicism (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1998), 39, 164.

[26] Fulton J. Sheen, God and Intelligence in Modern Philosophy: A Critical Study in the Light of the Philosophy of Saint Thomas (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1925), 83.