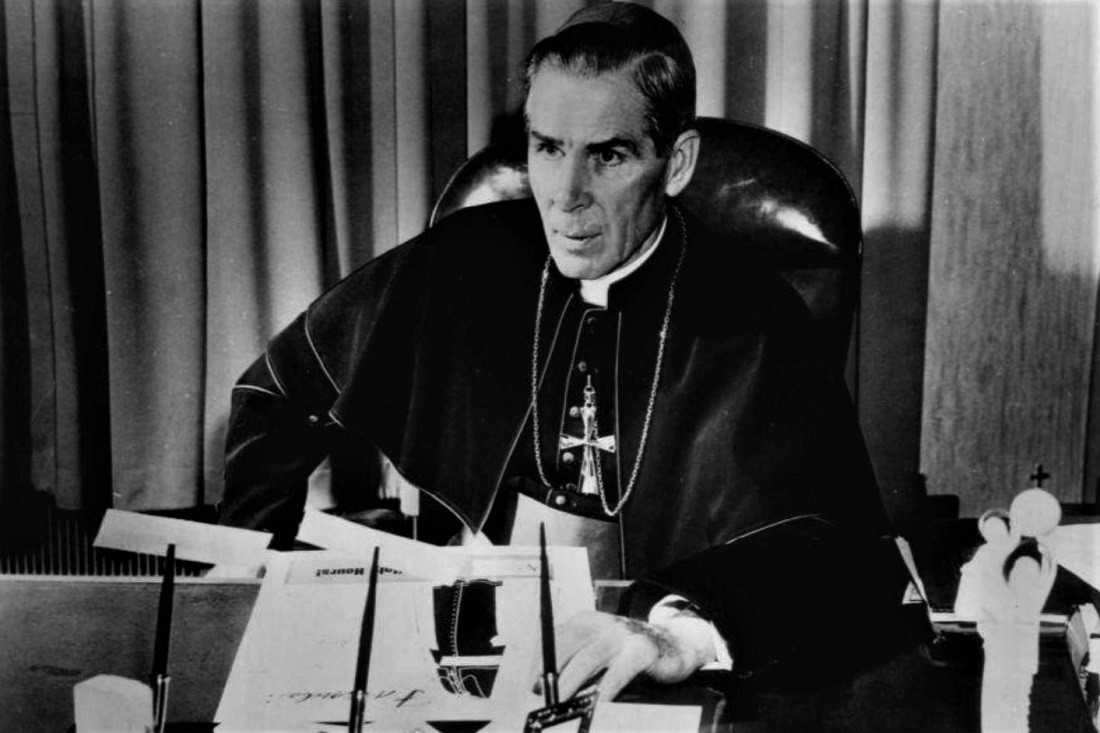

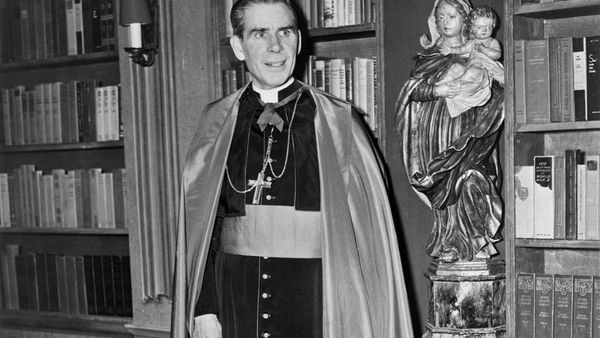

Perhaps no other prelate in the history of the United States could rival the positive impact of Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen (1895 – 1979) upon the work of evangelization in the United States. A household name in Catholic and non-Christian households alike, Sheen authored approximately 70 books in his lifetime, and he captivated millions of Americans through his newspaper columns and broadcasts on radio and television in the 1930’s, 40’s, and 50’s. It was not unusual for the mail he received to average 15,000 to 25,000 letters per day,[1] and it was estimated that thirty million people, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, tuned in to his programming each week.[2] His message was both simple and profound: Jesus Christ must be at the center of everything.

To what can we attribute Sheen’s success in proclaiming the Gospel in his work toward revitalizing the religious landscape of the United States? The key to Sheen’s success was his profound Eucharistic spirituality. We will focus on two things: 1) providing an introduction to Sheen’s Eucharistic spirituality by demonstrating the central role of the Eucharist in the life and teachings of Archbishop Sheen, and 2) suggest concrete steps that we can take to cultivate a healthy Eucharistic spirituality within our own lives.

Sheen’s profound love for the Eucharist manifested itself at an early age as a desire for future priestly ordination. When he received his First Communion at the age of twelve, he prayed for the gift of the priesthood. The fact that a strong desire for the priesthood was enkindled within him in the context of his First Communion was no coincidence, since the ultimate purpose of the priesthood is to be able to celebrate the Eucharist, the re-presentation in space and time of Jesus’ sacrifice ordered to the Father for the forgiveness of our sins. He was not content simply to receive the Eucharist; he wanted to be able actually to bring it about through the power of the sacrament of Holy Orders. He understood that the Eucharist was at the heart of the Church in general, and the priesthood in particular. Agreeing with Aquinas, Sheen reflected that “All the priest’s powers over the Mystical Body of Christ derive from his power over the True Body of Christ or the Eucharist.”[3]

It should come as no surprise that Fulton J. Sheen, a Catholic priest and bishop whom the Church recognizes as having lived a life of heroic virtue, celebrated Mass every day and understood that prayerful participation in the Mass is the strongest spiritual power available to us on this side of eternity. The Second Vatican Council reminds us in the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy that “the liturgy is the summit towards which the activity of the Church is directed; it is also the font from which all of her power flows.”[4] What I would like to focus upon in this paper is not Sheen’s love for the Mass, but rather his love for a particular devotion that both prepares for and extends beyond the duration of the Mass itself: Eucharistic adoration.

Pope Benedict XVI provides a helpful insight into the relationship between the Eucharistic liturgy and Eucharistic adoration:

The act of adoration outside Mass prolongs and intensifies all that takes place during the liturgical celebration itself. Indeed, "only in adoration can a profound and genuine reception mature. And it is precisely this personal encounter with the Lord that then strengthens the social mission contained in the Eucharist, which seeks to break down not only the walls that separate the Lord and ourselves, but also and especially the walls that separate us from one another.”[5]

In his autobiography entitled Treasure in Clay, Sheen recounts the story of a young martyr for the Eucharist that left a deep impression on him and helped to form his Eucharistic spirituality. Sheen recalls a story that took place in Communist China:

A priest had just begun Mass when Communists entered and arrested him and made him a prisoner . . . Shortly after his imprisonment, the Communists opened the tabernacle, threw the Hosts on the floor and stole the Sacred Vessels . . . About three o’clock one morning, he saw a child who had been at the morning Mass open a window, climb in, come to the sanctuary floor, get down on both knees, press her tongue to the Host to give herself Holy Communion . . . Every single night she came at the same time until there was only one Host left. As she pressed her tongue to receive the Body of Christ, a shot rang out. A Communist soldier had seen her. It proved to be her Viaticum.[6]

For his part, Sheen decided to make the Eucharist the centerpiece of his life and source of his apostolic and evangelical zeal by promising the Lord that he would make a Eucharistic Holy Hour every day of his priestly life. Not a single day of his priestly ministry went by without him making his Holy Hour, which at times required heroic virtue because of his frequent travels and speaking engagements. One “Holy Hour” that stood out in Sheen’s memory involved an hour in a Chicago church that turned into three. Sheen explains it as follows:

I asked permission from a pastor to go into his church to make a Holy Hour about seven o’clock one evening, for the church was locked. He then forgot that he had let me in, and I was there for about two hours trying to find a way of escape. Finally I jumped out of a small window and landed in the coal bin. This frightened the housekeeper, who finally came to my aid.[7]

During one trip in particular, Sheen was so exhausted from travel, that he fell asleep the moment he started the Holy Hour:

I knelt down and said a prayer of adoration, and then sat down to meditate and immediately went to sleep. I woke up exactly at the end of one hour. I said to the Good Lord: “Have I made a Holy Hour?” I thought His angel said: “Well, that’s the way the Apostles made their first Holy Hour in the Garden, but don’t do it again.”[8]

These accounts remind us how human Sheen was, and how accessible sanctity is for all of us. Here we have a lesson in humility, seeing how a man of Sheen’s stature recounting these events at the end of his life did not wince at the thought of telling us how he was locked inside a church and trying to find a way out for two hours, ultimately landing in a coal bin. We also have a lesson about being mindful of our own physical weaknesses and insufficiencies, for indeed the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak. Above all, we have a lesson in persistence. Not only did Sheen never miss a Holy Hour during his sixty years of priesthood, but he was found dead in front of the Blessed Sacrament in his private chapel within his New York apartment. He had died as he had lived: in the presence of the Lord.

Because the Holy Hour was a practice that Sheen himself took seriously and himself kept for 60 years, his insights on the purpose of the Holy Hour are uniquely important. When reflecting on why he decided on making a Holy Hour every day instead of once every week, Sheen states, “The Holy Hour should be a daily event because our crosses are daily, not weekly.”[9] He discusses the power of the daily Holy Hour to turn our crosses into crucifixes, thereby making them an aid to our sanctification rather than opportunities for grumbling. He uses other analogies as well to help us understand the reasons for a daily Holy Hour instead of a weekly one: “What mother is content to see her child once a week; what wife, her husband? Love is not intermittent. Medicines taken once a week can give little strength.”[10] I think a modern example in medicine that was unknown in his day but would make his analogy better understood is the antibiotic Zithromax, known better as a “Z-Pak.” In my experience, Zithromax has cured just about any type of infection I have ever had, and the directions for taking it were clear: every day a certain dosage had to be taken until none of the prescription was left, even if I started to feel remarkably better while some pills still remained. If I would have stopped taking the medicine once I thought I was better, the level of antibiotic in my system would not have been sufficiently strong enough to eradicate the bacteria which caused the infection. Things done in half-measure rarely produce lasting effects.

Regarding how to spend the hour of prayer before Jesus, Sheen prefers the traditional posture of kneeling, assuming that the person is physically able to do so and not impaired by illness or advanced age. He reflects, “It is best to kneel during the Hour, for it indicates humility, follows the example of our Lord in the Garden, makes atonement for our failings, and is a polite gesture before the King of Kings.”[11] Yet his reflections regarding the structure of the 60 minutes within the Holy Hour tend to depart from some traditional forms of Eucharistic piety, yet in a refreshing and down-to-earth way. He writes, “Some spiritual writers recommend a mechanical division of the hour into four parts: thanksgiving, petition, adoration, reparation.” He continues, “This is unnecessarily artificial. An hour’s conversation with a friend is not divided into four rigid segments or topics. The Holy Hour is not an official prayer; it is personal.”[12] Feeling strongly about the importance of an authentic encounter with Christ, instead of simply going through a set of preconceived motions in a set order, he said:

Many books on meditation have a rigid format . . . The so-called “methods” of meditation are generally impractical and unsuited to our mentality . . . A child will run after a ball with grace and freedom of movement. But if he is told to narrate what he does every second, how he first lifts the right foot, then the left, all the spontaneity disappears. To base a meditation, first on the intellect, then on the will, and finally on the emotions, is to destroy intimacy. This is not what really happens. . . . The person meditates; all his faculties work together. To achieve this, the greatest possible freedom should be left to the individual.[13]

Additionally, Sheen strongly encouraged the reading of scripture during the Holy Hour, suggesting that one should never make a Holy Hour without the scriptures.[14] In such an encounter, we contemplate the Word of God sacramentally present before us while at the same time being prayerfully immersed in the word of God contained and expressed within the scriptures. Sheen’s advice reminds us of the perennial Catholic way of “both/and.” We do not have to choose between nature or grace; we choose both. We do not have to choose between faith and reason; we choose both. We do not need to choose between adoring Our Lord sacramentally present in the Eucharist and meditating on his written word found in scripture—we are called to do both.

A final point that may be worth noting: a Holy Hour does not require the exposition of the Blessed Sacrament in the monstrance. More often than not, the Holy Hours made by Sheen were made in the presence of the Lord in the tabernacle of the church, and even today, the more common form of Eucharistic adoration outside of Mass is, in fact, adoration within a church where Our Lord is in the tabernacle, and not visibly exposed in a monstrance. This fact is especially encouraging for those of us who do not live in an area where perpetual adoration chapels or other opportunities to adore the Lord in the monstrance exist. While it is a noble aim to work towards having perpetual adoration chapels established, they are not necessary for gaining the graces of the Holy Hour, and they are not meant to be a replacement for the more ancient practice of adoring the Lord in the tabernacle.

Sheen prepared all of his sermons in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament, and one of his most important lessons he would teach about the Eucharist through his preaching and example was that we are to know Christ rather than simply knowing about Christ.[15] During the last decade or so of his life Sheen devoted himself to giving priestly retreats. The last conference he gave to his priestly retreatants was always a Holy Hour. This personal encounter with the Eucharistic Lord was indeed the key to his priestly and episcopal identity, and it was the precondition for his success in the work of evangelization. His love for the Eucharist was so intense and unwavering, that on one occasion as he was processing into the monastery church where he was beginning a priestly retreat, he was told that the tabernacle of this active church was empty. Inquiring about the situation, he was told that the church no longer used the tabernacle and that the Blessed Sacrament was reserved down the corridor. Sheen immediately halted the procession, and returned to the back of the church. When the bishop arrived on the scene to ask what was going on, Sheen informed the bishop that he would not begin the retreat until the Blessed Sacrament was returned to its proper place. Once the monks returned the Blessed Sacrament to the tabernacle, the retreat commenced.

Having traced some aspects of Fulton J. Sheen’s Eucharistic spirituality, we may now ask: What can we learn from his teaching and example?

The Lord Jesus Christ must be at the center of everything, and for a Catholic, the most direct access to the encounter with Jesus Christ is through the Mass celebrated and Eucharistic Host adored. For many people, the demands of their active lifestyles could compete with the hectic speaking, teaching, preaching, and retreat schedules of Fulton Sheen. They may not be able to reach the ideal of daily Mass and a daily Holy Hour, but they can definitely make it a priority to reserve some time each day to talk with Jesus; do their best to attend Mass beyond the requirements of liturgical law; and to incorporate regular periods of Eucharistic adoration into their lives. As we consider our daunting schedules, it may be helpful to ponder Sheen’s sage observation: “The time one has for anything depends on how much he values it.”[16]

In our day and age, we are called to be bold and courageous in our expression of love for the Eucharist, as Sheen illustrated through his refusal to give a priestly retreat, even in the presence of the bishop, without the Eucharist accorded the adoration it deserves. While some people may misunderstand us or misjudge our intentions, such a fear must never prevent us from making Our Eucharistic Lord our first love.

We are also called to be persistent in our love for Christ sacramentally present in the Eucharistic species. Sheen made his Eucharistic Holy Hour a daily event, a habit, and habits require discipline and persistence. We live in a country that seeks the “quick fix” to life’s many problems, or the easy “escape” from enduring difficulties, with a prime example of this being the staggering number of divorces. Our devotion to the Lord must be steadfast, not intermittent, so as to provide balance and clarity to our otherwise stressful and uncertain lifestyles.

We are also called to be authentic in the expression of our Eucharistic spirituality. There is no “one size fits all” spirituality within the Church, and so we are encouraged to discern the most effective way for us to grow in holiness. May we consider the insights and counsel of Archbishop Fulton Sheen as well as the collective wisdom of the Church’s innumerable saints, and incorporate into our own lives spiritual practices that align with our own personality within the boundaries of orthodoxy.

Pope St. John Paul II wrote, “Indeed, the Eucharist is the ineffable Sacrament! The essential commitment and, above all, the visible grace and source of supernatural strength for the Church as the People of God is to persevere and advance constantly in Eucharistic life and Eucharistic piety and to develop spiritually in the climate of the Eucharist.”[17] The closer one gets to the sun, the more the sun’s energy will engulfs them. The closer we get to the fireplace, the warmer we become. The more time we spend in close proximity with the Son of God and the Light of the World in the context of the Eucharistic Holy Hour, the more his light, life, and power will be channeled through our lives as we become veritable prisms, living icons of Christ.

[1] Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 66.

[2] Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 359.

[3] Fulton J. Sheen, The Mystical Body of Christ, 354.

[4] Sacrosanctum Concilium, §10.

[5] Pope Benedict XVI, Sacramentum caritatis, §66.

[6] Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 120.

[7] Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 189.

[8] Fulton J. Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 189.

[9] Fulton J. Sheen, The Priest Is Not His Own, 247.

[10] Fulton J. Sheen, The Priest Is Not His Own, 244.

[11] Fulton J. Sheen, The Priest Is Not His Own, 244.

[12] Fulton J. Sheen, The Priest Is Not His Own, 240.

[13] Fulton J. Sheen, The Priest Is Not His Own, 241 (emphasis original).

[14] See Fulton J. Sheen, Those Mysterious Priests, 183.

[15] See Fulton J Sheen, Treasure in Clay, 191.

[16] Fulton J. Sheen, Go To Heaven, 156.

[17] John Paul II, Redemptor Hominis, §20.