Words Matter

The words that we use connect to concepts, which, in turn, connect to the way we live our lives.[1] So, it is important to have clear and correct understanding of our words in order to promote right living. With all this in mind, I would like to explore two terms—ministry and apostolate—that we frequently encounter while working for the Church and how our understanding of these terms has pervasive effects on the work we do. For example, think of how we use 3D glasses. One can attempt to watch a 3D movie without 3D glasses, and the images will be blurry. One may, more or less, be able to make the images out, and even follow the movie, but clarity and detail will be lacking, critical elements may be missed, and the overall experience of the movie will be subpar. However, upon putting on the glasses the images become crystal-clear and show up in three-dimensional relief, and one will have a much better chance at experiencing the movie as intended.

Just so, a proper understanding of “ministry” and “apostolate” will provide a lens for understanding the work of a Church professional (parish/diocesan staff) so as to become more fruitful for the Kingdom.

Why? If the distinction between ministry and apostolate is not clearly understood, internalized, and applied, the parish ministry will continue to be focused on building up professional or quasi-professional ministers in the Church, rather than forming the laity for apostolate, which is the sanctification of the temporal order, the spreading of the Kingdom. This lens will allow us to see our work with clarity, and in multi-dimensional relief, like the difference between watching a 3D movie with 3D glasses, and watching one without. My intention is to provide some clarity for our understanding of “ministry” and “apostolate,” and to show how a clearer understanding can help us to be more effective in the work we do for the Kingdom. However, we must keep in mind that a proper understanding of these terms will not lead to immediate solutions. Yet, it will provide much more clarity in navigating innumerable situations and relationships in our work, so as to become more effective servants of the Church.

Disclaimer: We are going to keep our study simple. True, we could nuance these terms to no end and enumerate exception after exception. But we have to begin with an acceptable degree of simplicity and clarity so as to proceed in any meaningful way—in order to understand the nuances and exceptions for what they are: nuances and exceptions.

“Ministry” and “Apostolate”

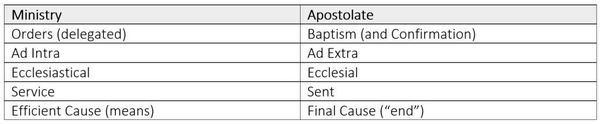

If one were to do a word search in ecclesial documents for the terms “ministry” and “apostolate” one would generally find information such as below.

Ministry flows from ordination.[2] In the Church’s language, ministry seems to be restricted to those functions that are proper to ordained men—ordained “ministers.”[3] Ministry refers to the threefold action of governance, preaching/teaching, and sanctification that is carried out by deacons, priests, and bishops (the hierarchy) in the name of the Church. Ministries can also be delegated to the lay faithful when there is need, and/or when certain individuals have the requisite competence/expertise to carry them out, such as in a parish and diocesan staff. In these cases, the pastor of the parish or the bishop of the diocese has delegated some aspect of his ministry to one who is competent to execute it. Moreover, ministry literally means “service,” and is directed ad intra, to the Church herself, for building up her members from within. Finally, ministry can be understood as the “efficient cause” of the faithful. An efficient cause is an agent that brings a thing into being or initiates a change. By providing the sacraments, preaching the Word, and governance, the ministry of the hierarchy brings the faithful into existence, and shepherds the faithful into deeper conversion.[4]

Apostolate, in the broadest sense, is “every activity of the Mystical Body that aims to spread the Kingdom of God” (CCC 864). However, there seems to be a special emphasis given to the laity when referring to the apostolate.[5] Thus, the apostolate flows from Baptism and Confirmation, and refers to the activity of the laity.[6] Also, whereas ministry is primarily directed ad intra, apostolate is primarily directed ad extra, to the sanctification and evangelization of the world. Apostolate refers to the Church as “sent” into the world. Apostolate is directed ad extra because of the “secular character” that is “proper and peculiar to the laity,” wherein they “contribute to the sanctification of the world, as from within like leaven (Lumen Gentium, §31).”[7]

Finally, one can understand apostolate as the “final cause” of ministry.[8] The final cause is the purpose or aim of an action, or the end toward which a thing naturally develops. We see this articulated very clearly in Pope Francis’ desire that “In all its activities the parish encourages and trains its members to be evangelizers” (Evangelii Gaudium, §28), and in the Catechism of the Catholic Church where it states that “the ‘Marian’ dimension of the Church precedes the ‘Petrine’” (§773).

Thus, for our purposes, we can summarize all of the above by saying that ministry can be thought of as the apostolic and evangelical activity of the Church’s ordained minister, while apostolate is the apostolic and evangelical activity of the lay faithful. The chart below visually distinguishes ministry and apostolate:

A Principle that Must Govern Parish (and Diocesan) Work

One can quickly begin to see that a deeper understanding of these terms has innumerable and immediate applications for the Pastor and parish ministry staff (who, in his/her profession, has been delegated an aspect of the Pastor’s ministry). Briefly and broadly, the goal of parish ministry (efficient cause) is the practical formation of the laity in holiness and apostolate (final cause). But for the purpose of this essay, we will introduce one general principle, and briefly touch on various specific applications.

The general principle: The parish should provide the minimum amount of necessary ministry structure in order to promote the greatest degree of personal apostolic initiative.

Think of this as an application of the principle of subsidiarity[9] from the Church’s social doctrine to the Church’s very own structure and governance. Subsidiarity basically says that 1) issues are best dealt with, and ought to be dealt with, by those who are closest to them, and 2) those who have care for the ones dealing with those issues should do all they can to support, promote, and develop them to take care of those issues themselves (in this case, the individual apostolate of the lay faithful).[10] The reasons are both theological and practical. Theologically, the apostolate of the laity is not an extension of the hierarchy but has its own legitimate autonomy;[11] and so when parish ministry overextends its reach into the sphere of the lay apostolate, there is an infringement of rights and confusion surrounding one’s vocation, spirituality, and mission/responsibility.[12] Since theology is truth about reality, this has practical repercussions.

For example, if an individual parishioner is hosting a small group in his/her home, and the parish staff attempts to control who participates in the group, keep track of attendance, enforce the use of particular resources, and the frequency and/or duration of the small group (as often happens in well-intentioned small group initiatives in parishes). This would likely result in a number of negative repercussions, including, but not limited to: The ministry staff will begin to feel responsible for what goes on in the living room of the parishioner, including the relationships and friendships that may or may not develop, if/how the group grows, conflicts that may arise between people, etc. The staff will feel pressure to get involved with these things and manage them. The parishioner will then feel managed and supervised, and will feel pressure to “produce” or perform well. He/she will lose a sense of responsible initiative, will become dependent on the parish staff, and will see him/herself as a volunteer of someone else’s program. Authentic friendships will have a more difficult time developing among group members due to the artificial manner in which the group was formed and the regular management from the parish staff. Everyone will expect start dates and end dates, rules, procedures, and curriculums. Potentially awkward interactions may take place between “participants” (because that is how they seem themselves and how the staff sees them) and parish staff. And the group will be very slow to reach beyond the pews, due to the heavy influence and management of ministry staff.

Thus when parish ministry is maximal in its exercise, it stifles personal apostolic initiative of the parishioners. The faithful are less likely to be intentional about personal apostolate, because they will either assume that “the parish will take care of it,” or feel micromanaged and supervised. This perpetuates, among both parish staff and parishioners, a program and volunteer mentality, passive attendance, clericalism, and spiritual immaturity. From the standpoint of the parish staff, this leads to staff who are, at best, unclear about their mission and sphere of influence. More typically, it perpetuates among the staff the “heresy of involvement,”[13] territorialism, and clericalism. This leads to forming staff who are oftentimes overworked, competitive with each other, are stretched too thin, and are ineffective; and therefore, have low morale and become highly dysfunctional. In short, the parish becomes a sort of “nanny state,” with many of the same characteristics.

To put it in terms of a general principle: Maximalist ministry fosters minimal personal apostolate, whereas minimalist ministry fosters maximal personal apostolate.

To put it yet another way, the ministry of each parish ministry staff (and the Pastor) must end where the personal apostolate of the parishioner begins. Thus, it is crucial to know precisely where ministry ends and apostolate begins, otherwise our language, projects, activities, etc. may inadvertently stifle the apostolate of our parishioners, shooting ministry efforts in the foot. Parish ministry should never result in the multiplication of ministries, committees, volunteers, programs, etc.[14] Rather, parish ministry must be highly focused on forming and equipping parishioners to be highly apostolic contemplatives in the middle of the world: aspiring “canonizeable saints” who have as their life mission the sanctification of the temporal order, which includes their families, friends, colleagues, acquaintances, their professional work, civic duties, and every setting in which they find themselves.

Further Application

Let us return to our above example, which was at the level of the individual, and apply this principle to “small group ministry” broadly. This is one of the hottest subjects of endeavor in today’s American parish. Small groups have been rightly identified, by everyone from Pope St. John Paul II to the local DRE, as an antidote to the stagnation that is so commonly experienced in our parishes, and as an opportunity for renewal. But again and again, small groups have failed to produce the transformative effect that was hoped for, both on an individual and community level. There may be many reasons for this, as diverse as the communities that have introduced small groups; but one entire category of reasons has to do with how parishes try to “run” small groups as a ministry.

First of all, “parish small group ministry” is a misnomer. When the above terms are properly understood, and the above principle applied, it is less accurate to think of the parish having small group ministry or “running” small groups, but rather a ministry of forming, equipping, and supporting parishioners to do intentional personal apostolate. Training them in small group facilitation skills is a very effective tool for it. However, when a parish does think of what its doing as “running parish small group ministry” it typically develops an ethos of managing and supervising people (some might call this herding cattle). The parish staff thinks it is up to them to organize and even dictate such things as: how long small groups should last, how often they need to meet, the types of resources they will allow people to use, who they will allow to be small group leaders, how small groups are supposed to multiply, small group demographics (how big groups can be, single-sex or coed groups, age groups, etc.), mandating and/or providing covenants, etc.

Now, the desire to control these things is likely all coming from the noblest of intentions—a zealous desire for the Gospel to have an effect on people’s lives and in society. To be clear, the parish staff does have the grave responsibility to provide formation, guidance, and support to parishioners (even individually selected parishioners) in their interior life and apostolate. And, in different communities and at different times, this may necessitate a higher degree of selection and “hand-holding,” especially early on in introducing small groups as intentional apostolate, or when introducing a cultural shift. But too much steering of the endeavor can stifle initiative, burn people out, and push them away.

In other words, when a parish staff thinks of itself as “running small group ministry,” that is precisely what they will end up doing. The staff will set themselves as responsible for the groups and what happens in them.[15] All of the repercussions in the above example will extend to the broader community. Parishioners will think of what they are doing as “for the parish.” They will see themselves as volunteers for a parish ministry, doing something for someone else—or they will see themselves as “special Catholic leaders.” The parish ministry staff will end up running a ministry of recruiting, training, managing, supervising, and retaining volunteers. They will get pulled into dramas that are not theirs, and, within a couple years, the project will either be abandoned, or put in the back seat of parish priorities. The initiative will be very slow to reach beyond the pews, due to the heavy influence and management of ministry staff—many, including the parish leadership, will view this initiative as one in and of the parish—and may even expect that it prioritizes “registered parishioners.”[16] The net result: another small group initiative that did not work.

For every parish community, there are likely dozens of other applications where the internalization and application of this principle could greatly help. These include the multiplication of committees, teams, and commissions; mandating ministry involvement for parishioners and Catholic school families; an overemphasis on “stewardship;” multiplication and centralization of ministries that could and therefore should be decentralized apostolates—whether organized or unorganized—such as pro-life, care for the poor, youth formation, and so on. Most, if not all of these applications typically stem from a perceived urgent need to fill a gap. In some cases these are necessary, but in most they are probably not, or are at least overdone.

What, Then, Should Ministry Staff be Doing?

So then what is the solution to this problem? A thorough examination and proposal of solutions greatly exceeds the scope of this article, which was simply to state the problem and articulate the principle. For now, we can offer some brief considerations.

As stated earlier, parish ministry staff must be highly focused on forming and equipping parishioners to be highly apostolic contemplatives in the middle of the world: aspiring “canonizeable saints” who have as their life mission the sanctification of the temporal order, which includes their families, friends, colleagues, acquaintances, their professional work, civic duties, and every setting in which they find themselves—putting Christ at the summit of all human activities.

This requires a methodology that is highly person-to-person and customizable to the individual. It will focus primarily on the formation of attitudes, virtues, and the acquisition of habitual spiritual practices proper to the secular character of the laity, rather than on skills-training. Moreover, these attitudes, virtues, and practices will be geared primarily to the sanctification of one’s personal vocation, profession, and relationships—all secular realities—rather than on ecclesiastical life. Helpful methodologies that will be the vehicle and engine to form parishioners as well as equip them for personal apostolate will include some form of small groups, and especially one-on-one accompaniment/guidance. All of these will be geared toward forming in parishioners a high degree of free and responsible initiative that is coupled with a high regard for the guidance and support offered by the ministry staff, who will, over time, be recognized more and more as a credible and excellent source of formation and guidance.

[1] A concept is “a universal and abstract content of the mind which makes us aware of the essence of a thing” (Brennan, Image of His Maker, 195). It is that by which one recognizes a universal nature of something in a mental image, which “transcends the senses and is not produced in the imagination, but by the intellect” (Feingold, Christian Anthropology, 43). In other words, it is the form of the object abstracted (the fruit of abstraction) from its individualized matter or, the intelligible form, as it is received in the intellect, which represents the object – that through which and in which the object is known.

[2] Consistently in ecclesiastical documents, both in text and in title, ministry is a reference to the work of those who are ordained.

[3] In fact, very often, the word “ministry” is often preceded and modified by the word “sacred.” This further indicates a connection to ordination, for example: “In this great field of complementary activity, whether considering the specifically spiritual and religious, or the consecratio mundi, there exists a more restricted area namely, the sacred ministry of the clergy” (Instruction on Certain Questions Regarding the Collaboration of the Non-ordained Faithful in the Sacred Ministry of Priesthood, “Premiss”).

[4] For an authoritative treatment of the stated dimensions of this topic, see: Instruction on Certain Questions Regarding the Collaboration of the Non-ordained Faithful in the Sacred Ministry of Priesthood.

[5] All Christians are called to participate in the Apostolate by virtue of Baptism and Confirmation. Confirmation is included here to signify the public character of the effects of Confirmation to “spread and defend the faith by word and action as true witnesses of Christ . . .” that strengthens one’s Baptismal faith for the apostolate (CCC, §1303). The documents of Vatican II never apply “ministry” to the function of the laity, however, references to that apostolate of the laity are abundant.

[6] Henceforth the term “apostolate,” in this more specific sense, will refer to the apostolate of the laity.

[7] “By reason of their special vocation, it belongs to the laity to seek the Kingdom of God by engaging in temporal affairs and directing them according to God’s will . . . they are called by God, that, being led by the spirit of the Gospel, they may contribute to the sanctification of the world, as from within like leaven . . .” (Lumen Gentium, §31).

[8] To be clear, holiness is the final cause of all ministry. However, since apostolate is nothing other than the overflow of holiness – holiness in action, directed outside of oneself: the “economy of holiness,” so to speak – one can also understand apostolate as the final cause of ministry.

[9] The Church is an incarnate theological society. Therefore, governance is intrinsic to its structure. And being a society with governance, it is subject to social doctrine.

[10] See: Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, §§185-188

[11] See: CCC, §§897, 900, 940.

[12] I am in no way proposing that this happens maliciously or through ill-will. Quite the contrary, this desire to “herd the sheep” usually comes from a deep resonance with (cf. Mt 9:36). The Church workers and pastors want so badly for the Gospel to have a real effect in people’s lives and on society that they try to try to do it all themselves, drawing up vast plans, and trying to “herd” people.

[13] The heresy of involvement is an attitude that suggests that the “good Catholic” is one who is involved in ecclesiastical or parish-centered activities, and the good parish is one who has more and more parishioners involved in ministries, programs, and activities. The more involved one is, the better a Catholic one is.

[14] To be sure, there will always be certain necessary ministries, volunteers, programs, and so on, but these should be minimal in number, and they will vary from parish to parish.

[15] It is crucial for parish staff to understand the distinction between “circle of influence” and “circle of concern.” From the perspective of the parish ministry staff, only those who they are dealing with directly, i.e., select small group leaders are in their circle of influence. The people in the leaders’ small groups are only in the staff’s circle of concern.

[16] To be clear, it is good and important for the parish staff to provide the formation and ongoing guidance that is necessary to develop parishioners into apostolic contemplatives; and sometimes this may involve providing certain healthy “crutches” to get them going, such as group sign-ups, material recommendations, etc. However, the crutches must be what is minimally necessary, and with a view towards weaning.