Advent begins on December 1 this year, meaning that the close of one liturgical year and the beginning of the next occur when November gives way to December. This coincidental alignment of the Gregorian and liturgical calendars joins two dispositions of the Church in the passing of one night: November’s remembrance of the dead and Advent’s hopeful anticipation of the coming of the Lord.

November begins with the Solemnity of All Saints and the Commemoration of All Souls. Throughout the month’s thirty days, the faithful intentionally recall the memory of our departed loved ones. We write their names in books of remembrance and we visit their graves. We cultivate our memory of the dead in longing for their eternal repose, while also longing to remain in relationship with them.

In the four weeks of Advent, we prepare our homes and our parishes for the coming of Christ. We cultivate our hearts and we hone our prayer to make room for the Word of God to take flesh in our midst. We take up practices that intentionally remind us of our need for a Savior. We rehearse our trust that he who has come will come again.

It is fitting that in both November and in Advent we give great attention to what we ourselves might do. We mourn, we long, then we remember, we hope. we pray, and we prepare. This awareness of what we do likely leads us to think of the actions of November as rather distinct from those of Advent, because we do different things in each. In one we mourn, in another we rejoice. In one we remember, in another we wait.

But this year, when November leads directly into Advent, the oddity of having to shift from one period to the next without even a day in between allows for a certain liminal awkwardness. If we attend to the unusual nature of this transition, some deeper truth might be revealed to us. The key to observing this truth rests in shifting our focus from our actions to God’s.

Whose Memory? Whose Hope?

When we remember our dead as we do in November, how much do we really rely on our own memory to uphold them? In the end, we know that our memories fade and that our powers are limited (at best) to give back to those now gone what they have lost, and what we have lost in losing them to death. When we pray for them, what are we really asking? When we remember them, what do we seek? Is it not true that undergirding all we do is a desperate plea for God to do something?

When we pray for our dead, we ask God to remember them; we ask that the God who once called them into existence when they were not would now bring them from death into life (See: Rom 4:17). So when we ourselves remember them, are we not really asking that God will remember us with them, so that who we are and who will shall become will not be separated from who or how or where we hope our loved ones shall be? In November, we appeal to God’s memory; it is God’s memory that abides.

Our trust in God’s memory at year’s end is rooted in the hope enkindle within us at the liturgical year’s beginning, when we start again in waiting for the Lord. But even if the emphasis falls upon our hope for the Lord’s coming each Advent, is it really true that the energy of our hoping animates the liturgical year’s beginning? No, it is not, because it is God’s action that causes us to hope.

What moves liturgical time is what God gives. Certainly, God gives all to us in the birth of Jesus, who lives through to the cross and is raised three days later from the grave. Yet, Advent is not the season of this gift, but only the gift’s anticipation. It is the time of anticipating what God will give. It is a time of waiting in hope—that is to say, it is a time of waiting by faith since “faith is the substance of things hoped for; the proof of things not seen” (Heb 11:1). The faith that hopes already glimpses, already tastes, already receives in advance that for which it waits. God gives to those who wait for him the gift of his presence in advance.

To hope is to already be touched by God, who gives himself in trust to those who entrust themselves to him. The spirit of Advent comes from a God who desires, for our God is a desiring God. Anyone who has ever loved someone knows that you lose yourself in hope before your beloved. They have a hold on you well before you ever truly behold them. So too in Advent, where our hope for the coming of Christ is already a sign that God has a hold on us.

What is true of our exercises to remember our dead is rooted in our exercises of hope in Advent. Our memories rely and appeal to God’s memory of our dead and of us with them, while our hope relies on and appeals to God’s gift which stirs up our hope in the first place. Beneath our action is God’s action.

The Mystery of Sleep

These are strange notions, which I do not fully understand. But I first came to glimpse something of this mysterious truth when some years ago I first read Charles Péguy’s Portal of the Mystery of Hope. In the course of his mesmerizing meditation on the second theological virtue, Péguy contemplates how our own hope comes from and depends upon God’s hope for us. God seeks us, so we seek God. God desires us, so we desire God. God waits for us before we ever think to wait for him. Péguy puts it like this:

God has taken the first step.

We must trust God since he has put his trust in us.

We must place our hope in God since he has so placed his in us.

It is unsettling to think of God as hoping because hope seems like weakness. You cannot control what you hope for; you make yourself subject to the possibility of hope’s fulfillment. That is a precarious position to be in, and one that indeed is a form of weakness for the one who dares to hope. And that is precisely the depth of the mystery of hope: God becomes weak for us. Moreover, God gives this weakness of hope to us as the strength of our desire. God places his hope in us so we might hope in him.

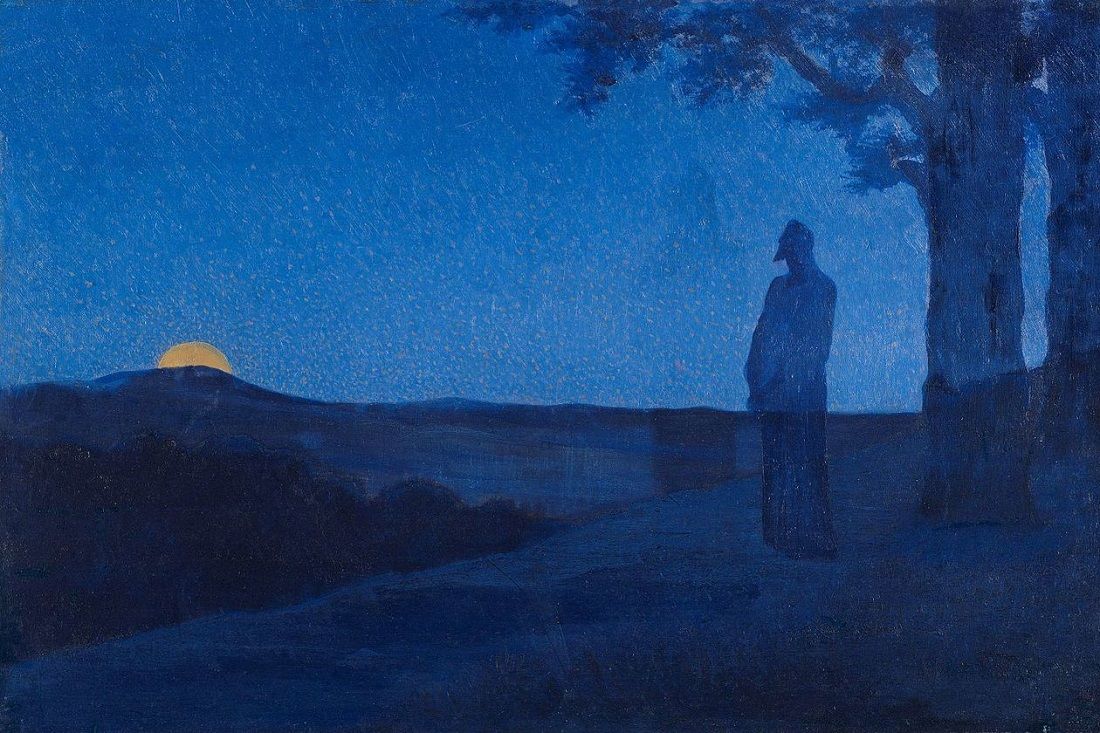

And when, according to Péguy, does God place this hope in us? When we sleep; when we exercise “the virtue of being able to do nothing.” That is to say, not during our periods of toil and achievement, not in our times of doing and acting. Instead, God gives us what we need most but could never have expected otherwise when we lie in wait, asleep. This gentle imposition of hope is the heart of Advent.

The night after I read Péguy’s poem for the first time, I began to pray a new prayer over my (then) only child as I put him down to sleep for the night. As I traced the sign of the cross on his forehead, I prayed these words for both of us: “Lord, renew your hope in us as we sleep.”

In praying thus, I prayed two prayers simultaneously:

- First, I asked that God never cease to love us, never stop searching for us, never tire of hoping for us.

- Second, I prayed that God would replenish again the hope he instills within us, so that we may also long for what he desires for us and never settle for anything less.

In other words, I prayed that God would hope in us and that God would place his hope within us. I still pray this prayer nightly over my children.

At Night and in the Grave

In praying this prayer for the renewal of hope at night, I have learned something about the mystery of sleep. I learned that the silence we enter in sleep relates to the silence we encounter when we call upon our beloved dead or visit their gravesites. We are silent at the end of the day and at the life. Our powers leave us when we sleep, and when we die we finally become powerless. November is dedicated to this end, the final sleep of death. We reach out for those who have lost their power in death, whom we are otherwise powerless to reach.

And in the deepest sense, Advent itself begins in sleep. There is no time before God makes the first move, before God desires us. It is God’s desire that makes us restless, and so we wait for God. When God comes, he comes as an infant in a manger—one who does not and cannot speak. He is as powerless as one who sleeps.

When his hour is at hand, Christ lays down his life upon the cross and enters into the final powerlessness of death: the most silent night of all. The one upon whom we wait in Advent comes to us in silence only to depart us for the silence of the grave, where the dead lie powerless. The mystery of the womb and the mystery of the tomb are united in him. This is who we wait for in Advent.

When he accepted our death, Christ renewed our sleep. He makes all of our sleep—each night and at the end of our lives—into a time of waiting in hope for the gift he seeks to give us: the gift of union in him. When we remember and pray for our dead, we already enjoy the substance of what we hope for because Christ claims them and us in him. The ones who have no power and we who are powerless to reach them are held together as one through the prayer and longing that reverberates through Christ. This hope is renewed every night and in every grave, but perhaps never so alluringly as in the passage from the last night of November to the first morning of Advent.

The unusual alignment of calendars this year signals for us what is always true: we abide in the sacred, liminal space between memory and hope. We remember our dead and we hope for their eternal repose. We remember the gift of the manger and of the cross, and we hope for the Lord to come in glory. We even dare to wager that God remembers us all in his memory and that God renews his hope in us as we sleep. He makes it OK to go to sleep weeping and then awake rejoicing in hope, because the hope God gives to us at the beginning of the liturgical year grows into our hope for our loved ones—and for ourselves with them—at the year’s end. And then we sleep and begin again, for every November begins in Advent.